Maestro Carmelo Pace (1906 - 1993) : a Proli C Twentieth-Century Composer, Musician and Music Educator.', the Educator., 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finley Is Falstaff by Ute Davis Those of Us Who Know the Slim, Handsome, Modest Dic Movement and Timing That Set Her Apart

é é é Soci t d' Op ra NATIONAL CAPITAL de la CAPITALE NATIONALE Opera Society Winter 2015 NEWSLETTER : BULLETIN Hiver 2015 Transformation!! Finley is Falstaff by Ute Davis Those of us who know the slim, handsome, modest dic movement and timing that set her apart. Her inter- Gerald Finley, simply stopped and gaped when he action with Sir John added vastly to my enjoyment. I un- appeared on the COC stage as the obese, overbear- derstand it even was her idea to give her coat, worn at the ing, pompous Sir John! The transformation was so Garter Inn encounter with Gerald Finley, the same lining complete and dramatic that it took the opening several material as was that of her dress. This would only be funny bars of music for me to realize that it really was Gerald to those of you who actually saw the COC production. Finley inside the masses of body padding and plastic Colin Ainsworth as Bardolfo and Robert face, neck and leg prostheses. Then he began to sing Gleadow as Pistola were appropriately disreputable and the Falstaff character truly came to life. in dress and behaviour, an excellent foil for Falstaff Indeed Finley’s Falstaff is, under the direc- whose dapper appearance whether in tweeds or hunt- tion of Robert Carsen, larger ing pink demonstrated the value than life, supremely funny and of a skilled tailor, no matter what superb entertainment. The your body shape.Lyne Fortin balance of comedy, some and Lauren Segal supplied the subtle and some obvious, with required charm and colour as moments of pathos was finely well as fine singing. -

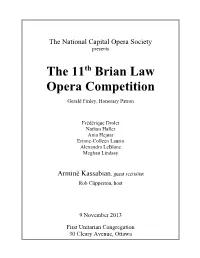

Brian Law Opera Competition Program

The National Capital Opera Society presents The 11th Brian Law Opera Competition Gerald Finley, Honorary Patron Frédérique Drolet Nathan Haller Ania Hejnar Erinne-Colleen Laurin Alexandra LeBlanc Meghan Lindsay Arminè Kassabian, guest recitalist Rob Clipperton, host 9 November 2013 First Unitarian Congregation 30 Cleary Avenue, Ottawa The National Capital Opera Society The National Capital Opera Society was founded by volunteer opera lovers in 1983, following the cancellation of the summer opera festival at the National Arts Centre. Today, to aid young, gifted singers of the National Capital Region, the Society holds the biennial Brian Law Opera Competition supported by the Brian Law Fund. We foster interest in opera with DVD showings, newsletters and social events for members. The Society also helps young singers striving to gain experience and recognition in opera by its financial contributions to the Opera Lyra Ottawa Young Artists Program and Pellegrini Opera as well as general support for operatic events in the National Capital Region. We always welcome new members who share our passion for opera and wish to join us in our activities. Gerald Finley, Honorary Patron The National Capital Opera Society is very proud to have as its patron the world- renowned bass-baritone Gerald Finley. Gerald began singing as a chorister at St. Matthew’s Church in Ottawa under the guidance of Brian Law and completed his musical studies at the Royal College of Music, King’s College, Cambridge, and the National Opera Studio. He was a winner of Glyndebourne’s John Christie Award. He is a Visiting Professor and Fellow of the Royal College of Music in London. -

Sir Colin Davis Discography

1 The Hector Berlioz Website SIR COLIN DAVIS, CH, CBE (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) A DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey With special thanks to Philip Stuart © Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey All rights of reproduction reserved [Issue 10, 9 July 2014] 2 DDDISCOGRAPHY FORMAT Year, month and day / Recording location / Recording company (label) Soloist(s), chorus and orchestra RP: = recording producer; BE: = balance engineer Composer / Work LP: vinyl long-playing 33 rpm disc 45: vinyl 7-inch 45 rpm disc [T] = pre-recorded 7½ ips tape MC = pre-recorded stereo music cassette CD= compact disc SACD = Super Audio Compact Disc VHS = Video Cassette LD = Laser Disc DVD = Digital Versatile Disc IIINTRODUCTION This discography began as a draft for the Classical Division, Philips Records in 1980. At that time the late James Burnett was especially helpful in providing dates for the L’Oiseau-Lyre recordings that he produced. More information was obtained from additional paperwork in association with Richard Alston for his book published to celebrate the conductor’s 70 th birthday in 1997. John Hunt’s most valuable discography devoted to the Staatskapelle Dresden was again helpful. Further updating has been undertaken in addition to the generous assistance of Philip Stuart via his LSO discography which he compiled for the Orchestra’s centenary in 2004 and has kept updated. Inevitably there are a number of missing credits for producers and engineers in the earliest years as these facts no longer survive. Additionally some exact dates have not been tracked down. Contents CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF RECORDING ACTIVITY Page 3 INDEX OF COMPOSERS / WORKS Page 125 INDEX OF SOLOISTS Page 137 Notes 1. -

Summer 2015 NEWSLETTER : BULLETIN Été 2015

Société d' Opéra National Capital de la Capitale Nationale Opera Society Summer 2015 NEWSLETTER : BULLETIN Été 2015 Brian Law Opera Competition 2015 Saturday, 10th October, 7pm Southminster United Church, 15 Aylmer Avenue, Ottawa. It’s time to mark your calendars for this year’s Brian Law The competition is made possible by generous ontributions to Opera Competition (BLOC), which is the National Capital the National Capital Opera Society’s Brian Law Fund. As a Opera Society’s principal event, held once every two years. registered charity, the NCOS is able to issue tax receipts for The programme is not yet fixed. Up to six finalists, chosen by donations of $20 or more. A hearty vote of thanks goes to all the preliminary jury, will each perform three arias with piano who have contributed to the success of the BLOC. Past win- accompaniment. At the end of the evening the winners will be ners have gone on to achieve stellar success and we are proud announced and prizes awarded. There is a $5000 first prize, to follow their illustrious accomplishments. Recent past win- $3000 for the runner up and $1000 (donated by board mem- ners include Meghan Lindsay (2013), Arminè Kassabian ber Pat Adamo) for the third placed finalist. Tickets to the (2011), Philippe Sly (2009), Yannick-Muriel Noah (2007), event cost $25 (students $10) and can be purchased at the Joyce El-Khoury (2005) and Joshua Hopkins (2003). door or reserved in advance by calling 613-830-9827. The competition is open to young singers focusing on a ca- reer in opera who were born, are resident or have studied voice in the National Capital Region. -

Ruby Mercer Fonds (Mus 278)

RUBY MERCER FONDS (MUS 278) Preliminary Processing Report Date of Accession: March 27, 1997 Inclusive Dates: 1922-1994, n.d. Description: Biographical documents; broadcast scripts; correspondence; concert programmes; lectures; reviews; interviews; writings (including That’s Our life - Quilico biography); contracts; awards and honours; brochures; notes; financial documents; periodicals; scrapbook; publicity; newsletters; press clippings; drawings; photographs of Ruby Mercer, her family and of various artists (including photographs dedicated to Ruby Mercer from Luciano Pavarotti, Rosa Poncelle, Claudio Arrau, Maria Pellegrini, Mariana Nicolesco, etc.); audio disc; audio tape cassette. Duplicates Removed: 3 cm. Documents tranferred : 5 cm of concert programmes, published scores and periodicals. Dimension: 2.85 m of textual documents. – 634 photographs. – 98 slides. – 8 negatives. – 1 audio tape cassette. – 1 audio disc. Boxing: October 9, 10, 14 -17; November 4-6; December 1-4, 1997; 170 folders; 16 boxes (14 upright; 2 flat - small). Conservation: 2 photographs to be restored (see last box of the fonds - flat box). Stéphane Jean December 8, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada MUSIC DIVISION - ARCHIVE'S PRELIMINARY PROCESSING FORM DIVISION DE LA MUSIQUE - BORDEREAU DE TRAITEMENT PRÉLIMINAIRE DES Title of Fonds/Titre du fonds DOCUMENTS D'ARCHIVES RUBY MERCER File Code of the Fonds (Accession Number)/Cote de fonds (Numéro d'acquisition) MUS 278 (1997-11) Box Number/Numéro de boîte Dimension 1 20 cm Restrictions Medium/Support Recorded Sound Audiovisual Machine Readable Photographic Enregistrement Sonore Audiovisuel Ordinolingue Photographique Imprimé Paper Other: Papier Autre: Date of/de Signature Page 1 of/de 1 description October 9, 1997 FOLDER DESCRIPTION CM DATE(S) CHEMISE 1 Broadcast scripts: Abduction from the Seraglio (Mozart); Acis and Galatea 2 cm 1955-1981, n.d. -

Turandot », « Rigoletto », « II Barbiere Di Siviglia », « La Traviata », « La Bohème », « Salome » Paul Lefebvre

Document généré le 24 sept. 2021 15:31 Jeu Revue de théâtre Six Spectacles de l’Opéra de Montréal « Turandot », « Rigoletto », « II Barbiere di Siviglia », « La Traviata », « La Bohème », « Salome » Paul Lefebvre En mille images, fixer l’éphémère : la photographie de théâtre Numéro 37 (4), 1985 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/27841ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc. ISSN 0382-0335 (imprimé) 1923-2578 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Lefebvre, P. (1985). Compte rendu de [Six Spectacles de l’Opéra de Montréal : « Turandot », « Rigoletto », « II Barbiere di Siviglia », « La Traviata », « La Bohème », « Salome »]. Jeu, (37), 164–173. Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc., 1985 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ six spectacles de l'opéra de montréal «turandot» «la traviata» «rigoletto» «la bohème» «il barbiere di siviglia» «salome» Turandot. Opéra en trois actes. Livret de Giuseppe La Traviata. Opéra en trois actes. Livret de Fran Adami et Renato Simoni, d'après la pièce Turan- cesco Maria Piave, d'après la Dame aux camélias dotte de Carlo Gozzi; musique de Giacomo Puccini, d'Alexandre Dumas fils; musique de Giuseppe Ver complétée par Franco Alfano. -

1966-67-Annual-Report.Pdf

110th ANNUAL REPORT THE CANADA COUNCIL 1966-67 &si?ciafe Direclor P.M. DWIER THE CANADA COUNCIL Honourable Judy LaMarsh, Secretary of State of Canada, Ottawa, Canada. Madam, 1 have the honour to transmit herewith, for submission to Parliament, the Report of The Canada Council for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1967, as required by section 23 of the Canada Council Act (5-6 Elizabeth II, 1957, Chap. 3). 1 am, Madam, Yours very truly, I June 30, 1967. THE CANADA Oneforty Wellington Street ) Members JEAN MARTINEAU (Chuimzn) MME ANNETTE LASALLE-LEDUC J. FRANCIS LEDDY (Vice-Chaimzn) NAPOLEON LEBLANC MURRAY ADASIUN DOUGLAS V. LEPAN JEAN ADRIEN ARSENAUL.T C. J. MACXENZIE ALEX COLVILLE TREVOR F. MOORE J. A. CORRY GILLES PELLETIER MRS. W. J. DORRANCE MISS KATHLEEN RICHARDSON MRS. STANLEY DOWHAN CLAUDE ROBILLARD W. P. GREGORY 1. A. RUMBOLDT HENRY D. HICKS SAMUEL STEINBERG STUART KEATE ) Investment Committee J. G. HUNGERFORD (Chairman) JEAN MARTINEAU G. ARNOLD HART TREVOR F. MOORE LOUIS HEBERT ) officefs JEAN BOUCHER, Director PETER M. DWYER, Associate Director F. A. MILLIGAN, Assistant Director ANDRE FORTIER, Assistant Director and Treasurer LILLJAN BREEN, Secretury JULES PELLETIER, Chief, Awards Section GERALD TAAFFE, Chief, Znformotion Services DAVID W. BARTLETT, SecretarpGeneral, Canadian National Commission for Unesco COUNCIL Ottawa 4 ) Advisory Bodies ACADEMIC PANEL JOHN F. GRAHAM (Chairman) BERNARD MAILHIOT EDMUND BERRY J. R. MALLORY ALBERT FAUCHER W. L. MORTON T. A. GOUDGE MALCOLM M. ROSS H. B. HAWTHORN CLARENCE TRACY J. E. HODGETTS MARCEL TRUDEL W. C. HOOD NAPOLEON LEBLANC MAURICE L’ABBE DOUGLAS V. LEPAN ADVISORY ARTS PANEL VINCENT TOVELL (Chairman) HERMAN GEIGER-TOREL LOUIS APPLEBAUM GUY GLOVER JEAN-MARIE BEAUDET WALTER HERBERT B. -

Six Spectacles De L'opéra De Montréal : « Turandot », « Rigoletto »

Document generated on 09/29/2021 8:43 p.m. Jeu Revue de théâtre Six Spectacles de l’Opéra de Montréal « Turandot », « Rigoletto », « II Barbiere di Siviglia », « La Traviata », « La Bohème », « Salome » Paul Lefebvre En mille images, fixer l’éphémère : la photographie de théâtre Number 37 (4), 1985 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/27841ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc. ISSN 0382-0335 (print) 1923-2578 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Lefebvre, P. (1985). Review of [Six Spectacles de l’Opéra de Montréal : « Turandot », « Rigoletto », « II Barbiere di Siviglia », « La Traviata », « La Bohème », « Salome »]. Jeu, (37), 164–173. Tous droits réservés © Cahiers de théâtre Jeu inc., 1985 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ six spectacles de l'opéra de montréal «turandot» «la traviata» «rigoletto» «la bohème» «il barbiere di siviglia» «salome» Turandot. Opéra en trois actes. Livret de Giuseppe La Traviata. Opéra en trois actes. Livret de Fran Adami et Renato Simoni, d'après la pièce Turan- cesco Maria Piave, d'après la Dame aux camélias dotte de Carlo Gozzi; musique de Giacomo Puccini, d'Alexandre Dumas fils; musique de Giuseppe Ver complétée par Franco Alfano. -

R13971 Poster Collection of the Music Division

R13971_Poster Collection of the Music Division Advertisement, with portrait of Walsh, "Canada's Blues Singer", at Madame's A1 Madame's|Walsh, Hock every Sunday to Wednesday. 36 x 22 cm ca.1980 Ontario, Mississauga Madame's Announcement, with portrait, for The Micah Barnes Trio at Bobbins May 24th to June A2 Micah Barnes Trio, The|Bobbins 4th. 36 x 22 cm Ontario, Toronto Bobbins Announcement for the New Music North Festival. Four evenings of contemporaray music at Lakehead University on June 21, 22, 24, and 25. Poster includes names of Jean McNutty Recital Hall, A3 New Music North Festival 2002 composers and performers 36 x 22 2002 06 21, 22, 24, 25 Ontario, Thunder Bay Lakehead University Announcement for "From the Mountains to the Sea" conducted by Brian Cameron, May A4 Musica Viva Singers 5. 36 x 22 cm ca. 2000 Ontario, Ottawa First Unitarian Congregation Announcement, with portrait, for MacMillan MacMillan, Scott|Chebucto talking about his compositions and leading A5 Symphony Orchestra the orchestra. 36 x 22 cm 2002 03 01 Nova Scotia, Halifax Saint Matthew's United Church Announcement for an "exploration of the Sharon Temple, the|Children of history and architecture and music of A6 Peace, the Sharon" 36 x 22 cm 1984 09 21-22 Ontario, Sharon Sharon Temple, the Announcement for "Music Week" and a workshop of Fleming music Anglican Chant and Hymns, church service and organ A7 Fleming, Robert recital. 28 x 22 cm 2001 11 17-18 Saskatchewan, Regina St. Paul's Anglican Cathedral Toronto Mendelssohn Youth A8 Choir|Earlscourt Citadel Band Annoucement for "the splendor of brass". -

Danse Dance Calendar

Scena_1.1.qxd 8/24/07 7:38 PM Page 1 AUTOMNE 2007 FALL VOL. 1.1 • 5,35$ En kiosque jusqu’au / Display until 2007-12-7 0 1 00 6655338855 2024861 15 19 Canada Post PMSA no. 40025257 scena1-1_pXX_Layout2_ads_c.qxd 8/22/07 8:22 PM Page 2 TROIS NOUVEAUX TRÉSORS DE MARIA CALLAS… …ETVILLAZON À SON MEILLEUR THE ONE AND ONLY OPERA HIGHLIGHTS Une compilation sur 2 CD des arias les plus appréciées, Un coffret à prix spécial, comprenant 8 CD de ses opéras les sélectionnées dans le catalogue des œuvres enregistrées plus importants et les plus appréciés. Au total, 103 spectacles. de La Callas…le tout au prix d’un seul disque !! DVD « THE ETERNAL MARIA CALLAS » Un nouveau DVD présentant des tournages récents et des métrages rares, incluant « Casta Diva » de l’opéra Norma, de Bellini; l’acte 2 de La Tosca, tiré de l’émission Ed Sullivan Show; ainsi que ses concerts au Royal Festival Hall, de même qu’à Tokyo. Durée totale, 146 minutes. VIVA VILLAZON (THE BEST OF ROLANDO VILLAZON) En moins de quatre ans, Villazon s’est élevé au rang des plus grandes stars de l’opéra. Cette compilation comprend une aria inédite ainsi qu’un DVD en prime contenant des extraits de son concert à Prague (nov. 2005). Le DVD comprend 60 minutes de métrage de ses concerts, dont neuf arias complètes et une ouverture. scena1-1_p03_ad_temp.qxd 8/25/07 1:46 AM Page 3 GAGNEZ DEUX ABONNEMENTS ABONNEZ-VOUS À LA SAISON 2007-2008 DE L'OPÉRA DE MONTRÉAL (UNE VALEUR DE 924 $) EN VOUS ABONNANT* À LA SCENA MUSICALE ET/OU À La SCENA (NOTRE NOUVELLE REVUE D'ARTS) WIN A PAIR OF 2007-08 SEASON 43 -

Buona Pasqua Happy Easter

IL POSTINO V O L . 6 N O . 10 MARCH 2005 / MARZO 2005 $2.00 Buona Pasqua Happy Easter CUSTOMER NUMBER: 04564405 IL POSTINO • OTTAWA, ONTARIO, CANADAPUBLICATION AGREEMENT NUMBER: 40045533 www.ilpostinocanada.com IL POSTINO Page 2 IL POSTINO March 2005 VOLUME 6 , NUMBER 8 865 Gladstone Avenue, Suite 101 • Ottawa, Ontario K1R 7T4 City-Wide (613) 567-4532 • [email protected] www.ilpostinocanada.com Publisher Preston Street Community Foundation Rapporto da Ottawa Italian Canadian Community Centre of the National Capital Region Inc. Executive Editor Angelo Filoso Il VIOXX di nuovo Managing Editor Carly Stagg alla ribalta? Associate Editor Marcus Filoso Di Carletto Caccia Continua la storia dell’antidolorifico VIOXX. Proprio in questi giorni le Graphic Designer autorita americane della Food and Drug Administration hanno di nuovo Vlado Franovic approvato questo farmaco e rilasciato il permesso per il suo ritorno sul mercato malgrado il parere negativo dello scienziato David Layout & Design Graham. Secondo lui, oltre 80.000 degli infarti occorsi negli Stati Uniti sono dovuti all’effetto dell’antidolorifico VIOXX. La decisione delle autorita Marcus Filoso americane e accompagnata dal mandato categorico di avvertire il consumatore sui potenziali danni che il farmaco puo causare al sistema Web site Manager cardio-circolatorio. Merita notare che lo stesso David Graham, funzionario Marc Gobeil presso la Food and Drug Administration, ha espresso il suo disappunto per la decisione presa a favore del VIOXX. Printing Qui in Canada la situazione e differente. Il ministro della sanita dovra Winchester Print & Stationary decidere a proposito del VIOXX quando avra ricevuto la domanda di approvazione dalla societa produttrice, la societa Merck & Co. -

Johns

SERVING THE BALTIMORE/WASHINGTON SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER! 995 CULTURAL CORRIDOR Johns. CIRCULATION 25,000 Peabod— <gnupjyiiHopkiny Newss s '95/'96 Season LAmcMhCmmt $ssue Baroness Katharine van Hogendorp's Memories of World War II page 21 The Prophetic -=3£M&S=_ THE GEORGE PEABODY ICENTENARY EXHIBITION opens at Peabody 07i&tJiiH>lu/&cimiI(f/ (iome& t& £/oiori/ page 10 page 16 Peabody News Sept/Oct 1995 SCOTT TENNAHT NICOLA HALL ' :„ • 16, 1995, •-.,".. .: * vy v 8:00 P.M. o • u Iff w» 6Ci J Ctwries St.'Baltirwre A ..•.•-. •.••.; • •.•••.i -.:.:: - ! : : : ] : ' '. ' .:•::• : ;.' ' : -';. ''. i : . .:: > •.:•:..•.,••:.•-..••.• ;"'.'•.!'• .:'..'':,.'•':.:".•. JASON VIEAUX PACO DE MALAGA & THE AHA MARTIHEI DAHCE Co. ... ... •• • . : i ...,.• : - :\; i 'i . : :: i ':.-:- :' v ' :• • - .. i : -: •'•:•: : • ': ;. : ... :-;;-; ••• . -.:<••• .••:• - ' ' •••: •••<:;.. , -ft-v.- • .- :. .-c! Guide T: :•••: < :...'V. •• :- ... :• . - • - •••::•-•. - T B says, " ennant is simply pht yoftwiiftftft.' :..•••••••••, ..-.:••...,- ••:••••.••• : ' •: -VS?.-- •• ..-- <« -•••. ••!• : ^^g:: c7 -': .... •» '"•;•. ' NORBERT KRAFT .••.:•.••:•:: ' , -., • 7 . :'g Malaga leained the. '..:. .. -.:. ', . :•.•.:. >'•;'., 1995, 8:00 PM I?t«t»r and cMno:<ft u'e-.'jit o'wcevins 1st f.rizf<ji :afef of Flam? ' > , •i. ftBfe-fc B.~ • . • •.••...• ...'.... * : credit. Ms. Martinez is.jtie jaugker ci the ......:.....•:.......... PV forbert Kraft enjoys t'< fit I N the world's fines; pi^nse:., '...... :...':"...'.;• ' . ' ' . •• ...... Asa re.. ••.•,• :•.••••.'-•:: :-. •-••••..•.•.: