CAPITOL SQUARE REVIEW and ADVISORY BOARD Et Al. V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maddie's Journey

2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF PHILANTHROPY Maddie’s Journey FROM THE DAY HER SURVIVAL WAS IN QUESTION, TO THE DAY WE SPENT WITH HER AT PHILADELPHIA’s independence hall. NAtionwide children’s hospitAL Twenty weeks before the day she was born, Maddie’s journey took an unexpected turn. 2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF PHILANTHROPY At 20 weeks into Emile’s second pregnancy, when Ten days after Maddie was born, cardiothoracic a routine ultrasound revealed a birth defect called surgeon, Dr. Mark Galantowicz and The Heart Dandy Walker, Emile and Chris Sower knew there Center team began the open-heart procedure at would be anxious days ahead. What the Sowers – 6 a.m. Seven hours later, Dr. Galantowicz emerged and doctors – didn’t know was that this birth defect from the operating room and told Maddie’s parents would be the least of Maddie’s medical challenges. that the operation was a success. One hurdle cleared: more to follow. For the next 20 weeks, the pregnancy went as planned and Maddie was born near her original Two days after successful heart surgery, Maddie due date. Then, during a routine examination, was still unable to keep food down. While it is not physicians at the birth hospital detected a uncommon for patients to experience difficulty heart arrhythmia. As a precaution, they made taking nourishment following heart surgery, her arrangements for Maddie to be transferred to parents grew concerned. Physicians ordered a Nationwide Children’s Hospital. CT scan and they discovered a bowel obstruction. Yes, Maddie was rushed into surgery again. But Upon her arrival, neonatologists examined Maddie 30 minutes into the operation, the surgeon walked and discovered a serious heart condition. -

Bulletin #46 November 14, 2020

Columbus City Bulletin Bulletin #46 November 14, 2020 Proceedings of City Council Saturday, November 14, 2020 SIGNING OF LEGISLATION (Legislation was signed by Council President Shannon Hardin on the night of the Council meeting, Monday, November 9, 2020; by Mayor Andrew J. Ginther on Wednesday, November 11, 2020; All legislation included in this edition was attested by the City Clerk, prior to Bulletin publishing.) The City Bulletin Official Publication of the City of Columbus Published weekly under authority of the City Charter and direction of the City Clerk. The Office of Publication is the City Clerk’s Office, 90 W. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215, 614-645-7380. The City Bulletin contains the official report of the proceedings of Council. The Bulletin also contains all ordinances and resolutions acted upon by council, civil service notices and announcements of examinations, advertisements for bids and requests for professional services, public notices; and details pertaining to official actions of all city departments. If noted within ordinance text, supplemental and support documents are available upon request to the City Clerk’s Office. Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 11/14/20) 2 of 250 Council Journal (minutes) Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 11/14/20) 3 of 250 Office of City Clerk City of Columbus 90 West Broad Street Columbus OH 43215-9015 Minutes - Final columbuscitycouncil.org Columbus City Council ELECTRONIC READING OF MEETING DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE DURING COUNCIL OFFICE HOURS. CLOSED CAPTIONING IS AVAILABLE IN COUNCIL CHAMBERS. ANY OTHER SPECIAL NEEDS REQUESTS SHOULD BE DIRECTED TO THE CITY CLERK'S OFFICE AT 645-7380 BY FRIDAY PRIOR TO THE COUNCIL MEETING. -

Downtown Columbus

1 2 3 4 5 HAMLET ST NEIL AVE AUDEN AVE POINTS OF Map KLEINER PRESCOTT ST O SHORT NORTH AVE DOWNTOWN FIRST AVE GILL SIXTH L PARK INTEREST (cont.) Symbol Grid KERR AL 670 E HUBBARD NERUDA AVE 315 AVE WILBER AVE N Ohio, State of OLUMBUS HENRY AVE HULL PERRY ST C ST T INGLESIDE H18 P8 CT CORNELIUS ST Bureau of Workers Comp. (BWC) - A WARREN AVE RD AVE QUALITY ST William Green Bldg. .......................................56 ............. B-3 N HUBBARD D ST HULL MICHIGAN AVE HULL AL A PEARL ST ST AVE R N POINTS OF Map ST G PL LUNDY ST Capitol................................................................. .............C-3 PL BOLIVAR ST R O ST LL H9HIGH ST E E E Y INTEREST Symbol Grid CIVITAS W Dept. of Health ................................................57 ............. B-3 V HENRIETTA ST L I ITALIAN D BUTTLES AVE AVE DELAWARE BUTTLES AVE 71 HARRISON AVE L R LINCOLN A Sawyer Office Bldg. .....................................................58 .............C-3 ADAMH........................................................... 1............C-4 Y T VILLAGE C G VICTORIAN H Office Bldg. .....................................................59 .............C-3 A N Park A AEP Building .................................................. 2............C-2 U ST A R BRICKEL CAPITOL Supreme Court................................................60 .............C-3 T B VILLAGE OLD LEONARD Annunciation - Greek Orthodox Cathedral.... 3............ A-3 N E VE ST THURBER DR. W, THURBER DR. A VIEW PL E R AVE Old Franklinton Cemetery.................................. 61............. C-1 Athenaeum..................................................... 4............C-4 L Wheeler Goodale AVE O DR One Columbus................................................... 62............. C-3 DR BalletMet Columbus....................................... 5............ B-4 Park S E. Park H15 E.A. N One Nationwide Plaza ....................................... 63..............B-3 I RUSSELL ST PARHAM ST L Broad St. -

County Line Rd Land

OFFERING MEMORANDUM Capital Markets | Investment Properties COUNTY LINE RD LAND 0 County Line Rd / Westerville, OH 43082 www.cbre.us/columbus TABLE OF CONTENTS 05 13 18 30 Executive Property Area Local Market Summary Description Overview Overview PLEASE CONTACT: ERIC BELFRAGE MICHAEL SHIREY NICOLE KOSTIUK Senior Vice President Vice President Client Services Specialist +1 614 430 5048 +1 614 430 5059 +1 614 430 5075 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] © 2020 CBRE, Inc. All rights reserved. 01 COUNTY LINE RD LAND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Affiliated Business Disclosure Disclaimer CBRE, Inc. operates within a global family of companies with many subsidiaries This Memorandum contains select information pertaining to the Property and and related entities (each an “Affiliate”) engaging in a broad range of the Owner, and does not purport to be all-inclusive or contain all or part of the commercial real estate businesses including, but not limited to, brokerage information which prospective investors may require to evaluate a purchase of services, property and facilities management, valuation, investment fund the Property. The information contained in this Memorandum has been obtained management and development. At times different Affiliates, including CBRE from sources believed to be reliable, but has not been verified for accuracy, Global Investors, Inc. or Trammell Crow Company, may have or represent completeness, or fitness for any particular purpose. All information is presented clients who have competing interests in the same transaction. For example, “as is” without representation or warranty of any kind. Such information includes Affiliates or their clients may have or express an interest in the property described estimates based on forward-looking assumptions relating to the general in this Memorandum (the “Property”), and may be the successful bidder for the economy, market conditions, competition and other factors which are subject Property. -

September 5, 2014

VOLUME XXXXVIIII NO. 33 SEPTEMBER 5, 2014 DATES TO REMEMBER SEPTEMBER 10, 2014 LEVERAGING NON-PROFIT ASSISTANCE & PUBLIC RESOURCES FOR CHILDREN SERVICES – A CCAO 2ND WEDNESDAY WEBINAR SEPTEMBER 10, 2014 NW DISTRICT COMMISSIONERS & ENGINEERS QUARTERLY MEETING, 180th FIGHTER WING NATIONAL GUARD, FULTON COUNTY (SWANTON) SEPTEMBER 11-12, 2014 CORSA BOARD RETREAT, ATWOOD LAKE RESORT, CARROLL COUNTY (SHERRODSVILLE) SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 CCC/EAPA REGIONAL TRAINING, CCAO OFFICES, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 CCAO AGRICULTURE & RURAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE MEETING, FRANKLIN COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF JFS, NORTHLAND VILLAGE, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 17, 2014 CCAO SMALL COUNTIES AFFAIRS COMMITTEE MEETING, CCAO OFFICES, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 18, 2014 CCAO GENERAL GOVERNMENT & OPERATIONS COMMITTEE, CCAO OFFICES, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 19, 2014 CCAO BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING, FRANKLIN PARK CONSERVATORY & BOTANICAL GARDENS, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 22, 2014 CCAO JOBS, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE MEETING, CCAO OFFICES, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 26, 2014 CCAO HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES COMMITTEE MEETING, CCAO OFFICES, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 26, 2014 CCAO JUSTICE & PUBLIC SAFETY COMMITTEE MEETING, CCAO OFFICES, COLUMBUS SEPTEMBER 30, 2014 CCAO TAXATION & FINANCE COMMITTEE, CCAO OFFICES, COLUMBUS DECEMBER 7-9, 2014 CCAO/CEAO ANNUAL WINTER CONFERENCE & TRADE SHOW, GREATER COLUMBUS CONVENTION CENTER, COLUMBUS 1 ASSOCIATION NEWS FULTON COUNTY TO HOST NW DISTRICT COMMISSIONERS & ENGINEERS ASSOCIATION Join Fulton County Commissioners Paul Barnaby, Perry Rupp, and William Rufenacht, County Engineer Frank Onweller and the 180th Fighter Wing Air National Guard for the NW District Commissioners and Engineers Quarterly Meeting to be held on Wednesday, September 10, 2014. Registration, lunch, 180th Fighter Wing briefing and tour, and the quarterly meeting will take place at the 180th Fighter Wing Air National Guard, 660 Eber Road in Swanton. -

State of Downtown Columbus

| 1 | 1 STATE OF DOWNTOWN COLUMBUS YEAR END 2018 e Prepared by Capital Crossroads & Discovery Special Improvement Districts | 2 GET A FREE RIDE. Downtown property owners pay for unlimited access to COTA’s entire bus system. Visit DowntownCpass.com to see if you and your company are eligible. 5 REASONS TO RIDE THE BUS 1. Save money: Fewer miles on your car equals fewer car-related expenses and no more parking fees. 2. No more parking hassles: Park for free at one of 25 Park & Rides and get downtown quick. 3. No more road rage: Let the COTA driver deal with traffic headaches. 4. Get a jump start on your day: Every bus has free Wi-Fi so catch up on email or text your bestie, and it won’t cost you a dime. 5. Unwind: Watch your favorite podcast or laugh at funny cat videos. When used on a white, color, or photographic background When used on a background field of black Colors: Colors: Process Black + White + PMS 1795 White + PMS 1795 A Capital Crossroads SID Program Powered by gohio commute www.DowntownCpass.com | 2 i ABOUT US | 3 Capital Crossroads Special Improvement District 670 (CCSID) is an association of more than 500 commercial and residential NEIL property owners in 38-square blocks HUNTINGTON NATIONWIDE of downtown Columbus. Its purpose PARK ARENA is to support the development of downtown Columbus as a clean, safe SPRING HIGH GRANT FOURTH FRONT and fun place to work, live and play. THIRD LONG GAY Hours of Operation: COLUMBUS MUSEUM OF ART 71 5:30 a.m. -

Bulletin #10 March 06, 2021

Columbus City Bulletin Bulletin #10 March 06, 2021 Proceedings of City Council Saturday, March 06, 2021 SIGNING OF LEGISLATION (Legislation was signed by Council President Shannon G. Hardin on the night of the Council meeting, Monday, March 1, 2021, with the exception of Ordinances 0104-2021 and 0111-2021 which were signed by President Pro Tem Elizabeth Brown; by Mayor, Andrew J. Ginther on Thursday, March 4, 2021; and attested by the City Clerk, prior to Bulletin publishing.) The City Bulletin Official Publication of the City of Columbus Published weekly under authority of the City Charter and direction of the City Clerk. The Office of Publication is the City Clerk’s Office, 90 W. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215, 614-645-7380. The City Bulletin contains the official report of the proceedings of Council. The Bulletin also contains all ordinances and resolutions acted upon by council, civil service notices and announcements of examinations, advertisements for bids and requests for professional services, public notices; and details pertaining to official actions of all city departments. If noted within ordinance text, supplemental and support documents are available upon request to the City Clerk’s Office. Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 03/06/21) 2 of 312 Council Journal (minutes) Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 03/06/21) 3 of 312 Office of City Clerk City of Columbus 90 West Broad Street Columbus OH 43215-9015 Minutes - Final columbuscitycouncil.org Columbus City Council Monday, March 1, 2021 5:00 PM City Council Chambers, Rm 231 REGULAR MEETING NO. 8 OF COLUMBUS CITY COUNCIL, MARCH 1, 2021 at 5:00 P.M. -

2016 Impact Report

DONORS MEMBERSHIP, DONATIONS, IN-KIND (10-1-15 THROUGH 9-30-16) $5,000+ Deborah Neimeth & Kristie Nicolosi Heather & Ryan Bone Aimee Deluca German Village Teeth Juvly Aesthetics Mike & Andrea McLane Heath & Jennifer Rittler Studio 33 Salon & Spa The Book Loft George Barrett Lisa & Charles Ohmer Robert & Amy Borman Paolo & Patricia DeMaria Whitening & Blowout Karla Kaeser Peter & Caroline McNally Debbie Roark Studio 595 Boutique GERMAN VILLAGE SOCIETY The Columbus Foundation James L Nichols Mark & Keriann Ours Patrick & Barbara Bowers Nate DeMars Steve & Maryellen Kahn Bridget McNeil Sue & David.Roark Studio Fovero Nurtur the Salon Jay Panzer & Jennifer Matthew & Kristen Diane Demko Germania Singing & Sport Amy Karnes Caitlin McTigue Cheryl Roberto & David Durr Suckel Darci Congrove & John Society Pribble Oberer’s Flowers Heitmeyer Bowersox Heather Densmore & Dax Kartson Emily Mead Magee Theresa Sugar Mike & Rachel Gersper Copious & Notes Panera Bread /Covelli James & Sarah Penikas Laura Bowman Matthew Sanders Sarah & John Kasey JT & Natalie Means Patricia Roberts Mark Sutter Charles Getzendiner COTA Enterprises Peter J Binning Attorney Donna Bowman Jeffrey Dersch Jeffrey Katz Christine Meer Kristen & Bryan Roberts Denise Suttles Pistacia Vera at Law Christopher Boyd Terri Dickey Heather McNees & Ben Jennifer Robinson Tom Dailey & Sung Jin Pak Gibson Aaron Keck Joseph Meranda Brian Sweet Jim Plunkett Richard & Sharon Pettit Ruth Boyd Mary DiGeronimo Lauren Robinson German Village Guesthouse Dennis Giglio & Michael Donna Keller Joyce Merryman -

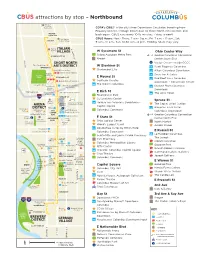

Cbus Map 5.10 Activities.Ai

® attractions by stop – Northbound Kroger .5 miles from stop COTA's CBUS® is the city's free Downtown Circulator, traveling from Brewery District, through Downtown to Short North Arts District, and 3RD AVE. & SAY AVE. back again. CBUS runs every 10-15 minutes, 7 days a week! The Market CBUS Hours: Mon.- Thurs. 7 a.m- 9 p.m., Fri. 7 a.m. - 12 a.m., Sat. 2ND AVE. Italian Village 9 a.m.- 12 a.m., Sun. 10:30 a.m.- 6 p.m., Holiday hours may vary. Oats & ITALIAN N. FOURTH ST. Barley VILLAGE W Sycamore St Ohio Center Way Scioto Audubon Metro Park Greater Columbus Convention E. PRESCOTT ST. Kroger Center South End NEIL AVE. SHORT NORTH Visitor Center – inside GCCC The Candle Lab ARTS DISTRICT W Blenkner St WARREN ST Hyatt Regency Columbus Shadowbox Live Marcia Evans Gallery Hilton Columbus Downtown Sharon Weiss Gallery Pizzuti Drury Inn & Suites Goodale Collection E Mound St Park E. RUSSELL ST. Red Roof Inn + Columbus Southern Theatre Brandt-Roberts Galleries Downtown – Convention Center The Westin Columbus Joseph Editions Le Méridien Columbus, Crowne Plaza Columbus Hammond The Joseph Harkins Galleries Downtown GOO E Rich St DALE BLVD. Hampton Inn The Cap at Union Station The Lofts Hotel & Suites Bicentennial Park SPRUCE ST. Cultural Arts Center Spruce St North Market Greater Columbus Holiday Inn Columbus Downtown – ARENA Arnold Convention Center The Cap at Union Station Statue Capitol Square DISTRCT Hilton Hampton Inn & Suites Huntington Columbus Commons Nationwide OHIO Hyatt Regency Park Arena Columbus Downtown CENTER Drury Inn & Suites NATIONWIDE BLVD. WAY Greater Columbus Convention Visitor Red Roof Plus+ E State St Center NATIONWIDE Center North End Nelson’s The Convenience BLVD. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize m aterials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812281 Private planning for economic development: Local business coalitions in Columbus, Ohio: 1858—1980 Mair, Andrew, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

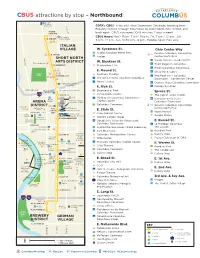

Attractions by Stop – Northbound

® attractions by stop – Northbound Kroger .5 miles from stop N. 4TH ST. COTA's CBUS® is the city's free Downtown Circulator, traveling from Brewery District, through Downtown to Short North Arts District, and 3RD AVE. & SAY AVE. back again. CBUS runs every 10-15 minutes, 7 days a week! The Market CBUS Hours: Mon.- Thurs. 7 a.m- 10 p.m., Fri. 7 a.m. - 12 a.m., Sat. E. 2ND AVE. Italian Village 9 a.m.- 12 a.m., Sun. 10:30 a.m.- 6 p.m., Holiday hours may vary. ITALIAN VILLAGE W. Sycamore St. Ohio Center Way Scioto Audubon Metro Park Greater Columbus Convention E. 1ST AVE. Kroger Center South End NEIL AVE. SHORT NORTH ARTS DISTRICT W. Blenkner St. Visitor Center – inside GCCC The Candle Lab Hyatt Regency Columbus E. WARREN ST. Shadowbox Live Hilton Columbus Downtown E. Mound St. Drury Inn & Suites Goodale Southern Theatre Park E. RUSSELL ST. Red Roof Inn + Columbus The Westin Great Southern Columbus Downtown – Convention Center Home2 Suites Le Méridien Columbus, Crowne Plaza Columbus Downtown The Joseph E. Rich St. Canopy by Hilton GOODALE BLVD. Hampton Inn The Cap at Union Station Bicentennial Park & Suites Spruce St. SPRUCE ST. Cultural Arts Center The Cap at Union Station Holiday Inn Columbus Downtown – North Hampton Inn & Suites Market Greater Columbus Capitol Square ARENA Arnold Convention Center Columbus Downtown Statue Columbus Commons Hilton Greater Columbus Convention Huntington DISTRICT Nationwide Hyatt Regency Center North End Park Arena OHIO E. State St. CENTER Drury Inn & Suites North Market NATIONWIDE BLVD. WAY Ohio Judicial Center Visitor Red Roof Plus+ Center Crowne Plaza Canopy by Hilton Arnold Statue Nelson’s World’s Largest Gavel Convenience E. -

Market Area Analysis Is to Review Available Economic and Demographic Data to Determine Whether the Local Market Will Undergo Economic Growth, Stabilize, Or Decline

Feasibility Study of Expansion of Headquarters Hotel Capacity Franklin County Convention Facilities Authority Columbus, Ohio Submitted to: William C. Jennison Executive Director Franklin County Convention Facilities Authority 400 North High Street Columbus, OH 43215 (614) 645-3900 (614) 645-3906 FAX Prepared by: HVS Convention, Sports & Entertainment Facilities Consulting A Division of HVS International 4445 West Erie, Suite 1-A Chicago, IL 60610 (312) 587-9900 Phone (312) 587-9908 Fax Web Site: www.hvsinternational.com December 21, 2001 HVS International Table of Contents Table of Contents Transmittal Letter 1. Executive Summary 2. Description of the Land and Neighborhood 3. Area Economic Analysis 4. Downtown Hotel Market Analysis 5. Convention / Meeting Industry Trends 6. Convention Center Demand Analysis 7. Hotel Occupancy Projections 8. Statement of Assumptions and Limiting Conditions 9. Certification December 21, 2001 Mr. William C. Jennison Executive Director Franklin County Convention Facilities 400 North High Street Columbus, OH 43215 (614) 645-3900 (614) 645-3906 FAX 445 West Erie Re: Feasibility Study- Expansion of Suite 1-A Headquarters Hotel Capacity Chicago, IL 60610 Columbus, Ohio (312) 587-9900 fax (312) 587-9908 www.hvsinternational.com Dear Mr. Jennison: Pursuant to your request, we herewith submit our feasibility study pertaining to the above-captioned study. We have inspected the site and facilities and analyzed the hotel market conditions in the Columbus area. The conclusions reached are based upon our present knowledge of lodging conditions in the competitive market, as of the completion of our fieldwork and research on September 12, 2001. We hereby certify that we have no undisclosed interest in the property, and our employment and compensation are not contingent upon our New York findings.