Furcy (April-June 1948)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haiti-Travel-Geo.Pdf

TRAVEL Haiti Back on the Map Travelling through Haiti, Caroline Eden discovers authentic Vodou ceremonies, unexpected mountain views and a country opening its arms to tourists PHOTOGRAPHS BY VIRAN DE SILVA AND CAROLINE EDEN CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE: Port-au-Prince ‘gingerbread’ houses n the outskirts of the town drumming. Shaking a quart bottle of Barbancourt from the 19th century; of Milot in northern Haiti, rum with one hand, Mafoun passes by leaving a Mafoun’s dancers – not night cloaks the hills like a trail of cigarette smoke in her wake. Her dancers, smoking or drinking but blanket. The air buzzes each one holding a lit candle, groove behind her, dancing with candles; a ‘tap tap’ bus – used as with mosquitoes. My feet forming a conga-like procession. They shake taxis, the name comes Osound feeble on wet cobblestones as I follow the their hips and nod their heads, moving trance- from the ‘tap’ that people sound of a rolling drumbeat made by many like around a large table laden with rum, silk give the side when they hands. A thin cloud shifts in the sky and flowers and popcorn that has been scattered like want to board or alight; suddenly a moonbeam illuminates an eerie confetti. These are gifts for summoning the Iwa drummers beating out white crucifix on the roadside. It quickly (spirit conversers). Milk-coloured wax drips a rhythm disappears again. Then, turning onto a dirt track, down the dancer’s brown arms. Sweat rolls in I enter a small hall. Roosters scuttle aside. Under rivulets off their faces. -

Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake

Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake a) b) Reginald DesRoches, M.EERI, Mary Comerio, M.EERI, c) d) Marc Eberhard, M.EERI, Walter Mooney, M.EERI, a) and Glenn J. Rix, M.EERI The 12 January 2010 Mw 7.0 earthquake in the Republic of Haiti caused an estimated 300,000 deaths, displaced more than a million people, and damaged nearly half of all structures in the epicentral area. We provide an overview of the historical, seismological, geotechnical, structural, lifeline-related, and socioeco- nomic factors that contributed to the catastrophe. We also describe some of the many challenges that must be overcome to enable Haiti to recover from this event. Detailed analyses of these issues are presented in other papers in this volume. [DOI: 10.1193/1.3630129] INTRODUCTION On 12 January 2010, at 4:53 p.m. local time, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the Republic of Haiti, with an epicenter located approximately 25 km south and west of the cap- ital city of Port-au-Prince. Near the epicenter of the earthquake, in the city of Le´ogaˆne, it is estimated that 80%–90% of the buildings were critically damaged or destroyed. The metro- politan Port-au-Prince region, which includes the cities of Carrefour, Pe´tion-Ville, Delmas, Tabarre, Cite Soleil, and Kenscoff, was also severely affected. According to the Govern- ment of Haiti, the earthquake left more than 316,000 dead or missing, 300,0001 injured, and over 1.3 million homeless (GOH 2010). According to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) the earthquake was the most destructive event any country has experienced in modern times when measured in terms of the number of people killed as a percentage of the country’s population (Cavallo et al. -

Focus on Haiti

FOCUS ON HAITI CUBA 74o 73o 72o ÎLE DE LA TORTUE Palmiste ATLANTIC OCEAN 20o Canal de la Tortue 20o HAITI Pointe Jean-Rabel Port-de-Paix St. Louis de Nord International boundary Jean-Rabel Anse-à-Foleur Le Borgne Departmental boundary Monte Cap Saint-Nicolas Môle St.-Nicolas National capital Bassin-Bleu Baie de Criste NORD - OUEST Port-Margot Cap-Haïtien Mancenille Departmental seat Plaine Quartier Limbé du Nord Caracol Fort- Town, village Cap-à-Foux Bombardopolis Morin Liberté Baie de Henne Gros-Morne Pilate Acul Phaëton Main road Anse-Rouge du Nord Limonade Baie Plaisance Milot Trou-du-Nord Secondary road de Grande Terre-Neuve NORD Ferrier Dajabón Henne Pointe Grande Rivière du Nord Sainte Airport Suzanne Ouanaminthe Marmelade Dondon Perches Ennery Bahon NORD - EST Gonaïves Vallières 0 10 20 30 40 km Baie de Ranquitte la Tortue ARTIBONITE Saint- Raphaël Mont-Organisé 0 5 10 15 20 25 mi Pointe de la Grande-Pierre Saint Michel Baie de de l'Attalaye Pignon La Victoire Golfe de la Gonâve Grand-Pierre Cerca Carvajal Grande-Saline Dessalines Cerca-la-Source Petite-Rivière- Maïssade de-l'Artibonite Hinche Saint-Marc Thomassique Verrettes HAITI CENTRE Thomonde 19o Canal de 19o Saint-Marc DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Pointe Pointe de La Chapelle Ouest Montrouis Belladère Magasin Lac de ÎLE DE Mirebalais Péligre LA GONÂVE Lascahobas Pointe-à-Raquette Arcahaie Saut-d'Eau Baptiste Duvalierville Savenette Abricots Pointe Cornillon Jérémie ÎLES CAYÉMITES Fantasque Trou PRESQU'ÎLE Thomazeau PORT- É Bonbon DES BARADÈRES Canal de ta AU- Croix des ng Moron S Dame-Marie la Gonâve a Roseaux PRINCE Bouquets u Corail Gressier m Chambellan Petit Trou de Nippes â Pestel tr Carrefour Ganthier e Source Chaude Baradères Anse-à-Veau Pétion-Ville Anse d'Hainault Léogâne Fond Parisien Jimani GRANDE - ANSE NIPPES Petite Rivières Kenscoff de Nippes Miragoâne Petit-Goâve Les Irois Grand-Goâve OUEST Fonds-Verrettes L'Asile Trouin La Cahouane Maniche Camp-Perrin St. -

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the Idps Camps (May 2013)

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the IDPs Camps (May 2013) 320,000 people are still living in 385 camps. 86 camps (22%) are particularly vulnerable to hydro-meteorological hazards (oods, landslides). Key figures Comparative maps from 2010 to 2013 of the number of IDPs in the camps Critical needs in camps by sector Camp Management: = 2010 2011 320 051 IDPs Anse-à-Galets Arcahaie Croix des bouquets Around 230,000 could still live in the camps at the end 2013 accor- ding to the most optimistic projections. It is necessary to continue Pointe -à-Raquette Cabaret eorts to provide solutions for return. = (52%) 166 158 Cité Soleil Cornillon Tabarre Thomazeau . Distribution of transitional shelters, Delmas . Grants rental houses, = (48%) Port-au-Prince 153 893 Gressier Pétion Ville Ganthier . Provision of livelihood Petit- Grand- Léogane Carrefour . Mitigation work in the camps. Goave Goave Kenscoff Source : DTM_Report_March 2013, Eshelter-CCCM Cluster Fact sheet Vallée = 385 camps de Jacmel Bainet Jacmel WASH: According to the latest data from the DTM made in March 2013: Number of IDPs and camps under . 30% of displaced families living in camps with an organization forced eviction 2012 2013 dedicated to the management of the site . 88% of displaced households have latrines/toilets in camps. 9% of displaced households have access to safe drinking water within the camps. = 73,000 individuals . 23% of displaced households have showers in the camps. (21,000 households) Source : DTM_Report_March 2013 = 105 camps of 385 are at risk of forced eviction Health: Malnutrition According to the 2012-2013 nutrition report screening of FONDEFH in 7 camps in the metropolitan area with a population of 1675 children and 1,269 pregnant women: Number of IDPs and camps from 2010 Number of IDPs . -

")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un

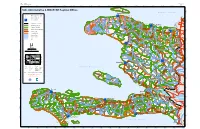

HAITI: 1:900,000 Map No: ADM 012 Stock No: M9K0ADMV0712HAT22R Edition: 2 30' 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W N o r d O u e s t N " 0 Haiti: Administrative & MINUSTAH Regional Offices ' 0 La Tortue ! ° 0 N 2 " (! 0 ' A t l a n t i c O c e a n 0 ° 0 2 Port de Paix \ Saint Louis du Nord !( BED & Department Capital UN ! )"(!\ (! Paroli !(! Commune Capital (!! ! ! Chansolme (! ! Anse-a-Foleur N ( " Regional Offices 0 UN Le Borgne ' 0 " ! 5 ) ! ° N Jean Rabel " ! (! ( 9 1 0 ' 0 5 ° Mole St Nicolas Bas Limbe 9 International Boundary 1 (!! N o r d O u e s t (!! (!! Department Boundary Bassin Bleu UN Cap Haitian Port Margot!! )"!\ Commune Boundary ( ( Quartier Morin ! N Commune Section Boundary Limbe(! ! ! Fort Liberte " (! Caracol 0 (! ' ! Plaine 0 Bombardopolis ! ! 4 Pilate ° N (! ! ! " ! ( UN ( ! ! Acul du Nord du Nord (! 9 1 0 Primary Road Terrier Rouge ' (! (! \ Baie de Henne Gros Morne Limonade 0 )"(! ! 4 ! ° (! (! 9 Palo Blanco 1 Secondary Road Anse Rouge N o r d ! ! ! Grande ! (! (! (! ! Riviere (! Ferrier ! Milot (! Trou du Nord Perennial River ! (! ! du Nord (! La Branle (!Plaisance ! !! Terre Neuve (! ( Intermittent River Sainte Suzanne (!! Los Arroyos Perches Ouanaminte (!! N Lake ! Dondon ! " 0 (! (! ' ! 0 (! 3 ° N " Marmelade 9 1 0 ! ' 0 Ernnery (!Santiag o \ 3 ! (! ° (! ! Bahon N o r d E s t de la Cruz 9 (! 1 ! LOMA DE UN Gonaives Capotille(! )" ! Vallieres!! CABRERA (!\ (! Saint Raphael ( \ ! Mont -

Haiti Study Abroad 2018 Water, Environmental Issues, and Service Learning May 20 (19 in GR) to June 19

Haiti Study Abroad 2018 Water, Environmental Issues, and Service Learning May 20 (19 in GR) to June 19 May 19th 4-6 pm - Pizza, Packing, and Parents party in Niemeyer MPR. Delta Air Lines 1369 20MAY Grand Rapids / Atlanta 8:10A 10:04A Delta Air Lines 685 20MAY Atlanta / PAP 11:20A-2:32P Delta Air Lines 684 19JUN PAP / Atlanta 3:30P-6:45P Delta Air Lines 1433 19JUN Atlanta / Grand Rapids 9:44P-11:43P OVERVIEW: • Saturday May 19, 4:00-6:00 pm Pizza, Packing, and Parent party Niemeyer Multipurpose Room, parents and friends invited. • Sunday, May 20th 6:00 am meet at Gerald R. Ford (GRR) Airport in Grand Rapids • Sunday, May 20th 8:10 am depart on Delta Flight DL 1369 • May 20th to May 23rd Staying at the Le Plaza Hotel, Port-au-Prince. • May 24th to May 26th Trip to Jacmel staying at Amitie Hotel. • May 27th travel to Deschapelles via PAP and airport stop at Moulin sur Mer museum en- route. • May 27 to June 10 Staying at HAS in Deschapelles, Haiti • June 11 to June 13 at UCI in Central Plateau (Pignon) • June 14 to June 18 in Cap Haitian at Auberge du Picolet Hotel • June 18 travel to PAP and stay at Servotel in Port au Prince • June 19 return flight to GRR FOR EMERGENCY CONTACT: Dr. Peter Wampler, Director ([email protected]): (US) (616) 638-2043 (cell) or (616) 331-2834 (office message) or +509 _____________ (Haiti Cell phone) Kelly McDonell, Assistant Director ([email protected]): (US) 248-459-4063 or (616) 331-8155 (office message) or +509 __________________ (Haiti Cell phone) Elena Selezneva (Padnos International Center) 616-331-3898 Rachel Fort (Hôpital Albert Schweitzer) + 509 3424-0465 (Haiti) [email protected] Leah Steele (Hôpital Albert Schweitzer) + 509 3735-8012 (Haiti) [email protected] Mahamat Koutami Adoum (HAS) + 509 3418-0700 (Haiti) [email protected] US Embassy Duty Officer in Haiti: +509 2229-8000 Boulevard du 15 October Tabarre 41, Route de Tabarre Port au Prince, Haiti Page 1 of 8 Daily Itinerary (subject to change as conditions warrant): Date Activity Contact Saturday, May 19 Pizza, packing, and Dr. -

Flash Appeal Haiti Earthquake

EARTHQUAKE FLASH AUGUST 2021 APPEAL HAITI 01 FLASH APPEAL HAITI EARTHQUAKE This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humani- Get the latest updates tarian Country Team (HCT) and partners. It covers the period from August 2021 to February 2022. OCHA coordinates humanitarian action to ensure On 16 August 2021, a resident clears a home that was damaged during the crisis-affected people receive the assistance and earthquake in the Capicot area in Camp-Perrin in Haiti’s South Department. protection they need. It works to overcome obstacles Photo: UNICEF that impede humanitarian assistance from reaching The designations employed and the presentation of material in the report do not people affected by crises, and provides leadership in imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of mobilizing assistance and resources on behalf of the the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area humanitarian system or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. www.unocha.org/rolac Humanitarian Response aims to be the central website for Information Management tools and services, enabling information exchange between clusters and IASC members operating within a protracted or sudden onset crisis. www.humanitarianresponse.info Humanitarian InSight supports decision-makers by giving them access to key humanitarian data. It provides the latest verified information on needs and delivery of the humanitarian response as well as financial contributions. www.hum-insight.com The Financial Tracking Service (FTS) is the primary provider of continuously updated data on global human- itarian funding, and is a major contributor to strategic decision making by highlighting gaps and priorities, thus contributing to effective, efficient and principled humani- tarian assistance. -

Cholera Treatment Facility Distribution for Haiti

municipalities listed above. listed municipalities H C A D / / O D F I **Box excludes facilities in the in facilities excludes **Box D A du Sud du A S Ile a Vache a Ile Ile a Vache a Ile Anse a pitres a Anse Saint Jean Saint U DOMINICAN REPUBLIC municipalities. Port-au-Prince Port-Salut Operational CTFs : 11 : CTFs Operational Delmas, Gressier, Gressier, Delmas, Pétion- Ville, and and Ville, G Operational CTFs : 13 : CTFs Operational E T I O *Box includes facilities in Carrefour, in facilities includes *Box N G SOUTHEAST U R SOUTH Arniquet A N P Torbeck O H I I T C A I Cote de Fer de Cote N M Bainet R F O Banane Roche A Bateau A Roche Grand Gosier Grand Les Cayes Les Coteaux l *# ! Jacmel *# Chantal T S A E H T U O SOUTHEAST S SOUTHEAST l Port à Piment à Port ! # Sud du Louis Saint Marigot * Jacmel *# Bodarie Belle Anse Belle Fond des Blancs des Fond # Chardonnières # * Aquin H T U O S SOUTH * SOUTH *# Cayes *# *# Anglais Les *# Jacmel de Vallée La Perrin *# Cahouane La Cavaillon Mapou *# Tiburon Marbial Camp Vieux Bourg D'Aquin Bourg Vieux Seguin *# Fond des Negres des Fond du Sud du Maniche Saint Michel Saint Trouin L’Asile Les Irois Les Vialet NIPPES S E P P I NIPPES N Fond Verrettes Fond WEST T S E WEST W St Barthélemy St *# *#*# Kenscoff # *##**# l Grand Goave #Grand #* * *#* ! Petit Goave Petit Beaumont # Miragoane * Baradères Sources Chaudes Sources Malpasse d'Hainault GRAND-ANSE E S N A - D N A R GRAND-ANSE G Petite Riviere de Nippes de Riviere Petite Ile Picoulet Ile Petion-Ville Ile Corny Ile Anse Ganthier Anse-a-Veau Pestel -

Community Radios April17

Haiti: Communication with communities - Mapping of community radio stations (Avr. 2017) La Tortue Bwa Kayiman 95.9 Port De Paix Zèb Tènite Saint Louis Kòn Lanbi 95.5 du Nord Anse A Foleur Jean Rabel Chamsolme Vwa kominotè Janrabèl Borgne Quartier Morin Bas Limbe Cap Haitien Vwa Liberasyon Mole Saint Nicolas Nord Ouest Bassin Bleu Pèp la 99.9 Port Margot Gros Morne Fransik 97.9 Pilate Plaine Baie de Henne Vwa Gwo Mòn 95.5 Eko 94.1 du Nord Caracol Bombardopolis Limbe Vestar FM Anse Rouge Milot Limonade Acul du Nord Terrier Rouge Ferrier Solidarité Terre Neuve Plaisance Natif natal Nord Trou du Nord Fort Liberte Zèb Ginen 97.7 Radyo Kominotè Sainte Suzanne Nòdès 92.3 Marmelade Gonaives Ouanaminthe Trans Ennery Dondon Nord Est Massacre Unité Bahon Valliere Capotille St. Raphael Tropicale 89.9 Capotille FM Ranquitte L'Estere La Victoire Mont Organise Saint-Michel de l'Attal Mombin Legend Desdunes Inite Sen Michel Pignon Crochu Carice Artibonite Tèt Ansanm 99.1 Grande Saline Communes ayant au moins Cerca Carvajal Dessalines/Marchandes une radio communautaire Maissade Radyo kominotè Mayisad Cerca La Source Communes sans Hinche radio communautaire Saint-Marc Vwa Peyizan 93.9 Imperial Petite Riviere de l'Artibonite Thomassique Cosmos Centre Xplosion Verrettes Thomonde Chandèl FM 106.1 Makandal 101.5 Xaragua 89.5 Grand’Anse 95.9 Boucan Carre Power Mix 97.5 Pointe A Raquette La Chapelle Kalfou 96.5 Arcahaie Lascahobas Tropette Evangelique 94.3 Belladere Orbite 100.7 Saut d'Eau Tet Ansanm 105.9 Anse A Galet Mirebalais CND 103.5 Cabaret Tera 89.9 -

Haiti – Dominican Republic: Environmental Challenges in the Border Zone

Haiti – Dominican Republic Environmental challenges in the border zone http://unep.org/Haiti/ This report was made possible by the generous contributions of the Government of Norway and the Government of Finland First published in June 2013 by the United Nations Environment Programme © 2013, United Nations Environment Programme United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, KENYA Tel: +254 (0)20 762 1234 Fax: +254 (0)20 762 3927 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNEP. The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP, or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Cover Image: © UNEP Photos: Unless otherwise credited, images in this report were taken by UNEP staff UNEP promotes Design and layout: Le Cadratin, Plagne, France environmentally sound practices globally and in its own activities. This publication is printed on recycled paper using eco-friendly practices. Our distribution policy aims to reduce UNEP’s carbon footprint. HAITi – DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Environmental challenges in the border zone United Nations Environment Programme Table of contents Foreword 4 Executive summary 6 Part 1 Background 10 1 Introduction 10 1.1 A challenging time for the border zone . -

H-2A Visa Program in Haiti

H-2A Visa Program in Haiti Worker Recruitment Services International Organization for Migration - Mission in Haiti PROGRAM PARTNERS International Organization for Migration (IOM), Haiti. Established in 1951, IOM is the leading intergovernmental organization in the field of migration and works closely with governmental, intergovernmental and non-governmental partners. US Association for International Migration (USAIM), Washington DC. As a registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, the U.S. Association for International Migration (USAIM) seeks to empower migrants. Through outreach, education, and fundraising USAIM aims to raise awareness about the reality of migration while encouraging positive action. USAIM supports programs of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) related to counter- trafficking, emergency relief, and migrant health. Protect the People (PTP), Washington DC. PTP is a network of professionals working to protect people affected by conflict and disaster. PTP provides technical experts to humanitarian agencies, fosters private sector partnerships for humanitarian response, and conducts training in protection for governments and the security sector. PTP has a network of fifty experts who speak eighteen languages and have worked in over eighty countries. PTP works closely with United Nations agencies, the U.S. Government, and non-governmental organizations throughout the world. Center for Global Development (CGD), Washington DC. CGD is the only research institute in Washington, DC - and now also in London - with a singular focus on development seen through the multiple facets of migration, aid, trade, debt, climate change, global health, education, and population. CGD combines rigorous research with strategic outreach and communications aimed at both informing and promoting meaningful policy change. Research and policy outreach conducted by CGD was influential in instigating the US government to extend the H-2 visa opportunity to Haitians in early 2012. -

Port-Au-Prince (May 1947-August 1948) En Route to Haiti (UH000, 001

The Paul-Henri and Erika Bourguignon Photographic Archives The Ohio State University Libraries Port-au-Prince (May 1947-August 1948) En route to Haiti (UH000, 001, 002) Paul Bourguignon arrived in Haiti in May 1947, having traveled from Le Havre to Martinique on board the French luxury liner Le Colombie. The boat had been converted into a military hospital ship and had not yet returned to its prewar character. It was crowded with emigrants from many different European countries, most of whom hoped to relocate in South America. From Martinique Bourguignon proceeded to Port-au- Prince, with stops on the way in Guadeloupe and the Dominican Republic. In Port-au-Prince, Bourguignon settled at the Hotel Excelsior on the Champ de Mars and soon began to take photographs. The city and its surroundings (PH003, 004, 005, 006, 007, 008, 009, 010, 011, 012, 013, 014, 015, 016, 017, 018, 019, 020, 021, 022, 023, 024, 025, 026, 027, 028, 029, 030) Port-au-Prince is located on the Gulf of Gonâve, named for the island at its center. The city was founded by the French, in the 18th century, as the capital and principal port of the colony of St. Domingue. In 1944--the most recent date for which US Government estimates were available in 1948--Port-au-Prince was reported to have a population of 125,000. Unofficial estimates in 1948 set the total closer to 200,000. The increase, by all accounts, was due to a continuous migration from rural areas to the city. This long term- trend was accelerated, on the one hand, by fragmentation and alienation of rural lands and on the other, by the availability of service jobs in the city.