Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Étude Sur La Santé Publique En République D'haïti

Étude sur la Santé Publique en République d’Haïti Juillet 2013 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) International Techno Center Co., Ltd. & S-Planning Inc. HM JR 13-072 Étude sur la Santé Publique en République d’Haïti Juillet 2013 Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA) International Techno Center Co., Ltd. & S-Planning Inc. Abréviations AFD Agence Française de Développement CAL Centre de Santé avec Lit CHU Centre Hospitalier Universitaire CSL Centre de Santé sans Lit DAB Direction de l'Administration et Budget, MSPP DELR Direction d'Épidémiologie, de Laboratoires, de Recherche, MSPP DOSS Direction d'Organisation des Service de Santé, MSPP DOTS Traitement de courte durée sous surveillance directe DRH Direction Des Ressources Humaines, MSPP DSF Direction de la Santé de la Famille, MSPP DSI Direction des Soins Infirmiers, MSPP DSNCRP Document de Stratégie Nationale pour la Croissance et pour la Réduction de la Pauvreté 2008-2010 EMMUS Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services FBP Financement basé sur la Performance HCR Hôpital Communautaire de Référence HD Hôpital Départemental HR Hôpital de Référence HUEH Hôpital de l’Université d’État d’Haïti MSPP Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population OMD Objectifs du millénaire pour le développement OMS Organisation mondiale de la Santé ONUSIDA Programme commun des Nations Unies sur le VIH/SIDA PARDH Plan d'Action pour le Relèvement et le Développement d'Haïti PDS Plan Directeur de Santé PNS Politique Nationale de Santé PSDH Plan Stratégique -

Haiti-Travel-Geo.Pdf

TRAVEL Haiti Back on the Map Travelling through Haiti, Caroline Eden discovers authentic Vodou ceremonies, unexpected mountain views and a country opening its arms to tourists PHOTOGRAPHS BY VIRAN DE SILVA AND CAROLINE EDEN CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE: Port-au-Prince ‘gingerbread’ houses n the outskirts of the town drumming. Shaking a quart bottle of Barbancourt from the 19th century; of Milot in northern Haiti, rum with one hand, Mafoun passes by leaving a Mafoun’s dancers – not night cloaks the hills like a trail of cigarette smoke in her wake. Her dancers, smoking or drinking but blanket. The air buzzes each one holding a lit candle, groove behind her, dancing with candles; a ‘tap tap’ bus – used as with mosquitoes. My feet forming a conga-like procession. They shake taxis, the name comes Osound feeble on wet cobblestones as I follow the their hips and nod their heads, moving trance- from the ‘tap’ that people sound of a rolling drumbeat made by many like around a large table laden with rum, silk give the side when they hands. A thin cloud shifts in the sky and flowers and popcorn that has been scattered like want to board or alight; suddenly a moonbeam illuminates an eerie confetti. These are gifts for summoning the Iwa drummers beating out white crucifix on the roadside. It quickly (spirit conversers). Milk-coloured wax drips a rhythm disappears again. Then, turning onto a dirt track, down the dancer’s brown arms. Sweat rolls in I enter a small hall. Roosters scuttle aside. Under rivulets off their faces. -

16 NEEDS Humani Overview

Humanitarian 16 0 2 NEEDS Overview People in Need 2.1m Dec 2015 Credit: OCHA Haiti HAITI This document is produced on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. This document provides the Humanitarian Country Team’s shared understanding of the crisis, including the most pressing humanitarian need and the estimated number of people who need assistance. It represents a consolidated evidence base and helps inform joint strategic response planning. The designations employed and the presentation of material in the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. www.haiti.humanitarianresponse.info Part one: Summary Humanitarian needs & keyfigures Impactofthecrisis Breakdown of people in need Severity of need 03 People in need 2.1M PART I: HUMANITARIAN NEEDS Humanitarian NEEDS& KEY FIGURES The humanitarian situation in Haiti has deteriorated considerably in 2015 due to the convergence of multiple humanitarian risk factors. These include a sharp increase in food insecurity resulting from drought and the prolonged effects of “El Nino”, the persistence of cholera and a protection crisis triggered by the forced / voluntary return of thousands of Haitians from the Dominican Republic. The immediate needs of the 60,000 people who remain displaced from the 2010 earthquake cannot be overlooked. Finally, the country has a high exposure to climate hazards and natural disasters coupled with limited national response capacity. Haiti remains a largely fragile environment from a governance and development perspectives with high insecurity, overpopulation, widespread poverty, huge economic inequalit ies, a dysfunctional health system, extremely poor access to safe water and sanitation, limited agricultural production, and high environmental degradation. -

Focus on Haiti

FOCUS ON HAITI CUBA 74o 73o 72o ÎLE DE LA TORTUE Palmiste ATLANTIC OCEAN 20o Canal de la Tortue 20o HAITI Pointe Jean-Rabel Port-de-Paix St. Louis de Nord International boundary Jean-Rabel Anse-à-Foleur Le Borgne Departmental boundary Monte Cap Saint-Nicolas Môle St.-Nicolas National capital Bassin-Bleu Baie de Criste NORD - OUEST Port-Margot Cap-Haïtien Mancenille Departmental seat Plaine Quartier Limbé du Nord Caracol Fort- Town, village Cap-à-Foux Bombardopolis Morin Liberté Baie de Henne Gros-Morne Pilate Acul Phaëton Main road Anse-Rouge du Nord Limonade Baie Plaisance Milot Trou-du-Nord Secondary road de Grande Terre-Neuve NORD Ferrier Dajabón Henne Pointe Grande Rivière du Nord Sainte Airport Suzanne Ouanaminthe Marmelade Dondon Perches Ennery Bahon NORD - EST Gonaïves Vallières 0 10 20 30 40 km Baie de Ranquitte la Tortue ARTIBONITE Saint- Raphaël Mont-Organisé 0 5 10 15 20 25 mi Pointe de la Grande-Pierre Saint Michel Baie de de l'Attalaye Pignon La Victoire Golfe de la Gonâve Grand-Pierre Cerca Carvajal Grande-Saline Dessalines Cerca-la-Source Petite-Rivière- Maïssade de-l'Artibonite Hinche Saint-Marc Thomassique Verrettes HAITI CENTRE Thomonde 19o Canal de 19o Saint-Marc DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Pointe Pointe de La Chapelle Ouest Montrouis Belladère Magasin Lac de ÎLE DE Mirebalais Péligre LA GONÂVE Lascahobas Pointe-à-Raquette Arcahaie Saut-d'Eau Baptiste Duvalierville Savenette Abricots Pointe Cornillon Jérémie ÎLES CAYÉMITES Fantasque Trou PRESQU'ÎLE Thomazeau PORT- É Bonbon DES BARADÈRES Canal de ta AU- Croix des ng Moron S Dame-Marie la Gonâve a Roseaux PRINCE Bouquets u Corail Gressier m Chambellan Petit Trou de Nippes â Pestel tr Carrefour Ganthier e Source Chaude Baradères Anse-à-Veau Pétion-Ville Anse d'Hainault Léogâne Fond Parisien Jimani GRANDE - ANSE NIPPES Petite Rivières Kenscoff de Nippes Miragoâne Petit-Goâve Les Irois Grand-Goâve OUEST Fonds-Verrettes L'Asile Trouin La Cahouane Maniche Camp-Perrin St. -

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the Idps Camps (May 2013)

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the IDPs Camps (May 2013) 320,000 people are still living in 385 camps. 86 camps (22%) are particularly vulnerable to hydro-meteorological hazards (oods, landslides). Key figures Comparative maps from 2010 to 2013 of the number of IDPs in the camps Critical needs in camps by sector Camp Management: = 2010 2011 320 051 IDPs Anse-à-Galets Arcahaie Croix des bouquets Around 230,000 could still live in the camps at the end 2013 accor- ding to the most optimistic projections. It is necessary to continue Pointe -à-Raquette Cabaret eorts to provide solutions for return. = (52%) 166 158 Cité Soleil Cornillon Tabarre Thomazeau . Distribution of transitional shelters, Delmas . Grants rental houses, = (48%) Port-au-Prince 153 893 Gressier Pétion Ville Ganthier . Provision of livelihood Petit- Grand- Léogane Carrefour . Mitigation work in the camps. Goave Goave Kenscoff Source : DTM_Report_March 2013, Eshelter-CCCM Cluster Fact sheet Vallée = 385 camps de Jacmel Bainet Jacmel WASH: According to the latest data from the DTM made in March 2013: Number of IDPs and camps under . 30% of displaced families living in camps with an organization forced eviction 2012 2013 dedicated to the management of the site . 88% of displaced households have latrines/toilets in camps. 9% of displaced households have access to safe drinking water within the camps. = 73,000 individuals . 23% of displaced households have showers in the camps. (21,000 households) Source : DTM_Report_March 2013 = 105 camps of 385 are at risk of forced eviction Health: Malnutrition According to the 2012-2013 nutrition report screening of FONDEFH in 7 camps in the metropolitan area with a population of 1675 children and 1,269 pregnant women: Number of IDPs and camps from 2010 Number of IDPs . -

World Bank Document

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: PIDA2769 Public Disclosure Authorized Project Name HT Center and Artibonite Regional Development (P133352) Region LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN Country Haiti Public Disclosure Copy Sector(s) Rural and Inter-Urban Roads and Highways (56%), Urban Transport (12%), Central government administration (10%), Public administratio n- Transportation (8%), General agriculture, fishing and forestry sector (14%) Theme(s) Rural services and infrastructure (60%), Natural disaster management (15%), Other urban development (15%), Other public sector gover nance (10%) Lending Instrument Investment Project Financing Public Disclosure Authorized Project ID P133352 Borrower(s) Ministry of Economy and Finance, MEF Implementing Agency Unite Technique d' Execution (UTE) Environmental Category B-Partial Assessment Date PID Prepared/Updated 12-Dec-2013 Date PID Approved/Disclosed 16-Jan-2014 Estimated Date of Appraisal 17-Jan-2014 Completion Estimated Date of Board 20-Mar-2014 Public Disclosure Authorized Approval Decision I. Project Context Public Disclosure Copy Country Context With a GDP per capita of US$771 in 2012, Haiti is the poorest country in the Americas. It is also one of the most unequal countries in the world (with a Gini coefficient of 0.59), lagging in social indicators (ranking 161 out of 186 in the 2013 Human Development Index). Over half its population of 10 million live on less than US$1.25 per day, and 78 percent live on less than US$2 per day. The country has been hit by multiple shocks, which have hampered economic growth and development. The repeated hurricanes, which have disproportionately large, negative impacts in Haiti, and the January 2010 earthquake are likely to have further exacerbated vulnerability. -

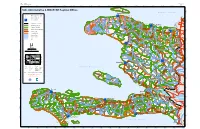

")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un

HAITI: 1:900,000 Map No: ADM 012 Stock No: M9K0ADMV0712HAT22R Edition: 2 30' 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W N o r d O u e s t N " 0 Haiti: Administrative & MINUSTAH Regional Offices ' 0 La Tortue ! ° 0 N 2 " (! 0 ' A t l a n t i c O c e a n 0 ° 0 2 Port de Paix \ Saint Louis du Nord !( BED & Department Capital UN ! )"(!\ (! Paroli !(! Commune Capital (!! ! ! Chansolme (! ! Anse-a-Foleur N ( " Regional Offices 0 UN Le Borgne ' 0 " ! 5 ) ! ° N Jean Rabel " ! (! ( 9 1 0 ' 0 5 ° Mole St Nicolas Bas Limbe 9 International Boundary 1 (!! N o r d O u e s t (!! (!! Department Boundary Bassin Bleu UN Cap Haitian Port Margot!! )"!\ Commune Boundary ( ( Quartier Morin ! N Commune Section Boundary Limbe(! ! ! Fort Liberte " (! Caracol 0 (! ' ! Plaine 0 Bombardopolis ! ! 4 Pilate ° N (! ! ! " ! ( UN ( ! ! Acul du Nord du Nord (! 9 1 0 Primary Road Terrier Rouge ' (! (! \ Baie de Henne Gros Morne Limonade 0 )"(! ! 4 ! ° (! (! 9 Palo Blanco 1 Secondary Road Anse Rouge N o r d ! ! ! Grande ! (! (! (! ! Riviere (! Ferrier ! Milot (! Trou du Nord Perennial River ! (! ! du Nord (! La Branle (!Plaisance ! !! Terre Neuve (! ( Intermittent River Sainte Suzanne (!! Los Arroyos Perches Ouanaminte (!! N Lake ! Dondon ! " 0 (! (! ' ! 0 (! 3 ° N " Marmelade 9 1 0 ! ' 0 Ernnery (!Santiag o \ 3 ! (! ° (! ! Bahon N o r d E s t de la Cruz 9 (! 1 ! LOMA DE UN Gonaives Capotille(! )" ! Vallieres!! CABRERA (!\ (! Saint Raphael ( \ ! Mont -

Hti Irma Snapshot 20170911 En.Pdf (English)

HAITI: Hurricane Irma – Humanitarian snapshot (as of 11 September 2017) Hurricane Irma, a category 5 hurricane hit Haiti on Thursday, September 7, 2017. On HAITI the night of the hurricane, 12,539 persons Injured people Bridge collapsed were evacuated to 81 shelters. To date, Capital: Port-au-Prince Severe flooding 6,494 persons remain in the 21 centers still Population: 10.9 M Damaged crops active. One life was lost and a person was recorded missing in the Centre Department Partially Flooded Communes while 17 people were injured in the Artibonite Damaged houses Injured people 6,494 Lachapelle departments of Nord, Nord-Ouest and Ouest. Damaged crops Grande Saline persons in River runoff or flooding of rivers caused Dessalines Injured people Saint-Marc 1 dead partial flooding in 22 communes in the temporary shelters Centre 1 missing person departments of Artibonite, Centre, Nord, Hinche Port de Paix out of 12,539 evacuated Cerca Cavajal Damaged crops Nord-Est, Nord-Ouest and Ouest. 4,903 Mole-St-Nicolas houses were flooded, 2,646 houses were Nord Limonade NORD-OUEST Cap-Haitien badly damaged, while 466 houses were Grande Rivière du Nord severely destroyed. Significant losses were Pilate Gros-Morne also recorded in the agricultural sector in the Nord-Est Bombardopolis Ouanaminthe Ouanaminthe (severe) NORD departments of Centre, Nord-Est and Fort-Liberté Gonaive Nord-Ouest. Caracol NORD-EST Ferrier Terrier-Rouge 21 The Haitian Government, with the support of Trou-du-Nord ARTIBONITE humanitarian partners, is already responding Nord-Ouest active Hinche in the relevant departments to help the Anse-à-Foleur Port-de-Paix affected population. -

Projet De La Réhabilitation D'urgence Et De L'appui À La Reconstruction Pour La République D'haïti Rapport Final (Rés

République d’Haïti Ministère de la Planification et de la Coopération Externe (MPCE) Projet de la réhabilitation d’urgence et de l’appui à la reconstruction pour la République d’Haïti Rapport final (Résumé) Novembre 2011 Agence Japonaise de Coopération International (JICA) Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. EID JR 11-135 Taux de change (taux moyen (TTS)) : moyenne des taux de mai à octobre 2010 (6 mois) 1,00 dollar américain = 88,00 yens japonais 1,00 dollar américain = 40.00 HTG (Haïtian Gourde) (Source : Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ) Préface L’Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale a décidé de mettre en œuvre le Projet de la Réhabilitation d’Urgence et de l’Appui à la Reconstruction pour la République d’Haïti, et a confié ledit Projet à Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. L’équipe d’étude a eu une série de discussions avec les parties concernées de la République d’Haïti de mai 2010 à juillet 2011, et a effectué une reconnaissance du site objet du projet. À la suite des études supplémentaires au Japon, le présent rapport a été finalisé. J’espère que ce rapport contribuera à la promotion du projet et au renforcement des liens d’amitié entre nos deux pays. Pour finir, je souhaite exprimer toute ma gratitude aux parties concernées du gouvernement d’Haïti pour leur coopération étroite apportée à l’équipe d’étude. Novembre 2011 Kiyofumi KONISHI Directeur Général Département de l’infrastructure économique Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale Le projet de la réhabilitation d’urgence et de l’appui à la reconstruction pour la République d’Haïti Rapport final (Résumé) Table des matières Préface Table des matières Plan de disposition Photos Liste des abréviations Arrière-plan Organigramme de l’étude A. Appui à l’élaboration du Plan de base du développement territorial .................................. -

The Impacts of the Haiti 2010 Earthquake on Water and Sanitation in Port-Au- Prince: a Case Study

THE IMPACTS OF THE HAITI 2010 EARTHQUAKE ON WATER AND SANITATION IN PORT-AU- PRINCE: A CASE STUDY Author: Pierre Charles Denis SUMMER 2015 GLOBAL WATER PARTNERSHIP LINNEGATAN 87D, STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN Pierre Charles Denis, Global Water Partnership, Summer 2015 Table of contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………….3 1.1 Background 1.2 Water challenges in Haiti 1.2.1 Infrastructure 1.2.2 Management 2. Post-disaster decisions and actions……………………………….5 2.1 Water delivery 2.2 Solid and hazardous waste management 2.3 Sanitation 2.4 Health 3. Disaster risk reduction management-case of Haiti…………9 4. Outcomes and Lessons learnt………………………………………10 5. References…………………………………………………………………..11 6. Author and contact………………………………………………………12 1 Pierre Charles Denis, Global Water Partnership, Summer 2015 Abbreviations DINEPA Haitian Water and Sanitation National Directorate IDB Inter-American Development Bank MSPP Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population NGOs Non-governmental Organizations PAHO Pan American Health Organization SMCRS Haitian Department of Solid Waste Management SWANA Solid Waste Association of North America UN United Nations UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNEP United Nations Environment Programme UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund USGS United States Geological Survey WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene WHO World Health Organization 2 Pierre Charles Denis, Global Water Partnership, Summer 2015 1. Introduction 1.1 Background Haiti is located in the Caribbean. It occupies the western part of the island of Hispaniola which it shares with Dominican Republic. It is 27, 750 square km in size and its capital city is Port-au-Prince. Map of Haiti (howtoenjoy.co.uk) January 12th, 2010 is an indelible day in the memory of all Haitians. -

Republic of Haiti

Coor din ates: 1 9 °00′N 7 2 °2 5 ′W Haiti Haiti (/ heɪti/ ( listen); French: Haïti [a.iti]; Haitian ˈ Republic of Haiti Creole: Ayiti [ajiti]), officially the Republic of Haiti (French: République d'Haïti; Haitian Creole: Repiblik République d'Haïti (French) [8] [note 1] Ayiti) and formerly called Hayti, is a Repiblik Ayiti (Haitian Creole) sovereign state located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican Republic.[11][12] Haiti is 27 ,7 50 square kilometres (10,7 14 sq mi) in Flag Coat of arms size and has an estimated 10.8 million people,[4] making it the most populous country in the Caribbean Motto: "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" (French)[1] Community (CARICOM) and the second-most "Libète, Egalite, Fratènite" (Haitian Creole) populous country in the Caribbean as a whole. The "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" region was originally inhabited by the indigenous Motto on traditional coat of arms: Taíno people. Spain landed on the island on 5 "L'union fait la force" (French) [2] December 1492 during the first voyage of Christopher "Inite se fòs" (Haitian Creole) Columbus across the Atlantic. When Columbus "Union makes strength" initially landed in Haiti, he had thought he had found Anthem: La Dessalinienne (French) [13] India or China. On Christmas Day 1492, Columbus' Desalinyèn (Haitian Creole) flagship the Santa Maria ran aground north of what is "The Dessalines Song" 0:00 MENU now Limonade.[14][15][16][17] As a consequence, Columbus ordered his men to salvage what they could from the ship, and he created the first European settlement in the Americas, naming it La Navidad after the day the ship was destroyed. -

Introduction

CENTER FOR EXCELLENCE IN DISASTER MANAGEMENT AND HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE (CFE-DM) CASE STUDY SERIES Case Study No. 6 • A review of Operation Unified Response, the U.S. military’s effort in support of Haiti following the January 2010 Earthquake Introduction On January 12, 2010, a massive earthquake struck southwest of Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. The magnitude 7.0 earthquake,1 the strongest to strike Haiti in 200 years, lasted for 35 seconds, killing 230,000 people, injuring 300,000 and displacing 1.6 million.2 The day following the earthquake, U.S. President Barack Obama ordered a whole of government response to the disaster. The Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA), part of the U.S. Agency for Interna- tional Development (USAID) led the massive undertaking, marshalling the collective resources of the entire U.S. interagency community, to include the U.S. Department of Defense. Ultimately, over 22,000 members of the U.S. armed services participated in Operation Unified Response, the name of the U.S. military’s effort in support of the Haitian people. “I have directed my administration to respond with a swift, coordinated, and aggressive effort to save lives. The people of Haiti will have the full support of the United States in the urgent effort to rescue those trapped beneath the rubble, and to deliver the humanitarian relief -- the food, water and medicine -- that Haitians will need in the coming days. In that effort, our government, especially USAID and the Departments of State and Defense are working closely together and with our partners in Haiti, the region, and around the world.” -President Barack Obama, January 13, 20103 This case study provides an overview of the U.S.