Burial Rites, Women's Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haiti-Travel-Geo.Pdf

TRAVEL Haiti Back on the Map Travelling through Haiti, Caroline Eden discovers authentic Vodou ceremonies, unexpected mountain views and a country opening its arms to tourists PHOTOGRAPHS BY VIRAN DE SILVA AND CAROLINE EDEN CLOCKWISE FROM ABOVE: Port-au-Prince ‘gingerbread’ houses n the outskirts of the town drumming. Shaking a quart bottle of Barbancourt from the 19th century; of Milot in northern Haiti, rum with one hand, Mafoun passes by leaving a Mafoun’s dancers – not night cloaks the hills like a trail of cigarette smoke in her wake. Her dancers, smoking or drinking but blanket. The air buzzes each one holding a lit candle, groove behind her, dancing with candles; a ‘tap tap’ bus – used as with mosquitoes. My feet forming a conga-like procession. They shake taxis, the name comes Osound feeble on wet cobblestones as I follow the their hips and nod their heads, moving trance- from the ‘tap’ that people sound of a rolling drumbeat made by many like around a large table laden with rum, silk give the side when they hands. A thin cloud shifts in the sky and flowers and popcorn that has been scattered like want to board or alight; suddenly a moonbeam illuminates an eerie confetti. These are gifts for summoning the Iwa drummers beating out white crucifix on the roadside. It quickly (spirit conversers). Milk-coloured wax drips a rhythm disappears again. Then, turning onto a dirt track, down the dancer’s brown arms. Sweat rolls in I enter a small hall. Roosters scuttle aside. Under rivulets off their faces. -

Gender Assessment Usaid/Haiti

GENDER ASSESSMENT USAID/HAITI June, 2006 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DevTech Systems, Inc. GENDER ASSESSMENT FOR USAID/HAITI COUNTRY STRATEGY STATEMENT Author: Alexis Gardella DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. 2 Gender Assessment USAID/Haiti TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 6 Executive Summary 7 1. GENDER DIFFERENTIATED DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS 9 1.1 Demographics 1.2 Maternal Mortality 1.3 Fertility 1.4 Contraceptive Use 1.5 HIV Infection 10 1.6 Education 1.7 Economic Growth 11 1.8 Labor 1.9 Agriculture and Rural Income 1.10 Rural and Urban Poverty 1.11 Environmental Degradation 12 2. GENERAL OVERVIEW OF GENDER IN HAITIAN SOCIETY 13 2.1 Status of Haitian Women 2.2 Haitian Social Structure: Rural 15 2.2.1 Community Level 2.2.2 Inter-Household Level 2.2.3 Intra-Household relations 16 2.2.4 Economic Division of Labor 2.3 Economic System 18 2.4 Urban Society 19 3. ONGOING USAID ACTIVITIES IN TERMS OF GENDER FACTORS OR 20 GENDER-BASED CONSTRAINTS 3.1 Sustainable Increased Income for the Poor (521-001) 3.2 Healthier Families of Desired Size (521-003) 22 3.3 Increased Human Capacity (521-004) 23 3.4 Genuinely Inclusive Democratic Governance Attained (521-005) 3.5 Streamlined Government (521-006) 24 3.6 Tropical Storm Recovery Program (521-010) 25 4. -

Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake

Overview of the 2010 Haiti Earthquake a) b) Reginald DesRoches, M.EERI, Mary Comerio, M.EERI, c) d) Marc Eberhard, M.EERI, Walter Mooney, M.EERI, a) and Glenn J. Rix, M.EERI The 12 January 2010 Mw 7.0 earthquake in the Republic of Haiti caused an estimated 300,000 deaths, displaced more than a million people, and damaged nearly half of all structures in the epicentral area. We provide an overview of the historical, seismological, geotechnical, structural, lifeline-related, and socioeco- nomic factors that contributed to the catastrophe. We also describe some of the many challenges that must be overcome to enable Haiti to recover from this event. Detailed analyses of these issues are presented in other papers in this volume. [DOI: 10.1193/1.3630129] INTRODUCTION On 12 January 2010, at 4:53 p.m. local time, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck the Republic of Haiti, with an epicenter located approximately 25 km south and west of the cap- ital city of Port-au-Prince. Near the epicenter of the earthquake, in the city of Le´ogaˆne, it is estimated that 80%–90% of the buildings were critically damaged or destroyed. The metro- politan Port-au-Prince region, which includes the cities of Carrefour, Pe´tion-Ville, Delmas, Tabarre, Cite Soleil, and Kenscoff, was also severely affected. According to the Govern- ment of Haiti, the earthquake left more than 316,000 dead or missing, 300,0001 injured, and over 1.3 million homeless (GOH 2010). According to the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) the earthquake was the most destructive event any country has experienced in modern times when measured in terms of the number of people killed as a percentage of the country’s population (Cavallo et al. -

Focus on Haiti

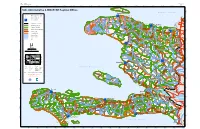

FOCUS ON HAITI CUBA 74o 73o 72o ÎLE DE LA TORTUE Palmiste ATLANTIC OCEAN 20o Canal de la Tortue 20o HAITI Pointe Jean-Rabel Port-de-Paix St. Louis de Nord International boundary Jean-Rabel Anse-à-Foleur Le Borgne Departmental boundary Monte Cap Saint-Nicolas Môle St.-Nicolas National capital Bassin-Bleu Baie de Criste NORD - OUEST Port-Margot Cap-Haïtien Mancenille Departmental seat Plaine Quartier Limbé du Nord Caracol Fort- Town, village Cap-à-Foux Bombardopolis Morin Liberté Baie de Henne Gros-Morne Pilate Acul Phaëton Main road Anse-Rouge du Nord Limonade Baie Plaisance Milot Trou-du-Nord Secondary road de Grande Terre-Neuve NORD Ferrier Dajabón Henne Pointe Grande Rivière du Nord Sainte Airport Suzanne Ouanaminthe Marmelade Dondon Perches Ennery Bahon NORD - EST Gonaïves Vallières 0 10 20 30 40 km Baie de Ranquitte la Tortue ARTIBONITE Saint- Raphaël Mont-Organisé 0 5 10 15 20 25 mi Pointe de la Grande-Pierre Saint Michel Baie de de l'Attalaye Pignon La Victoire Golfe de la Gonâve Grand-Pierre Cerca Carvajal Grande-Saline Dessalines Cerca-la-Source Petite-Rivière- Maïssade de-l'Artibonite Hinche Saint-Marc Thomassique Verrettes HAITI CENTRE Thomonde 19o Canal de 19o Saint-Marc DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Pointe Pointe de La Chapelle Ouest Montrouis Belladère Magasin Lac de ÎLE DE Mirebalais Péligre LA GONÂVE Lascahobas Pointe-à-Raquette Arcahaie Saut-d'Eau Baptiste Duvalierville Savenette Abricots Pointe Cornillon Jérémie ÎLES CAYÉMITES Fantasque Trou PRESQU'ÎLE Thomazeau PORT- É Bonbon DES BARADÈRES Canal de ta AU- Croix des ng Moron S Dame-Marie la Gonâve a Roseaux PRINCE Bouquets u Corail Gressier m Chambellan Petit Trou de Nippes â Pestel tr Carrefour Ganthier e Source Chaude Baradères Anse-à-Veau Pétion-Ville Anse d'Hainault Léogâne Fond Parisien Jimani GRANDE - ANSE NIPPES Petite Rivières Kenscoff de Nippes Miragoâne Petit-Goâve Les Irois Grand-Goâve OUEST Fonds-Verrettes L'Asile Trouin La Cahouane Maniche Camp-Perrin St. -

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the Idps Camps (May 2013)

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the IDPs Camps (May 2013) 320,000 people are still living in 385 camps. 86 camps (22%) are particularly vulnerable to hydro-meteorological hazards (oods, landslides). Key figures Comparative maps from 2010 to 2013 of the number of IDPs in the camps Critical needs in camps by sector Camp Management: = 2010 2011 320 051 IDPs Anse-à-Galets Arcahaie Croix des bouquets Around 230,000 could still live in the camps at the end 2013 accor- ding to the most optimistic projections. It is necessary to continue Pointe -à-Raquette Cabaret eorts to provide solutions for return. = (52%) 166 158 Cité Soleil Cornillon Tabarre Thomazeau . Distribution of transitional shelters, Delmas . Grants rental houses, = (48%) Port-au-Prince 153 893 Gressier Pétion Ville Ganthier . Provision of livelihood Petit- Grand- Léogane Carrefour . Mitigation work in the camps. Goave Goave Kenscoff Source : DTM_Report_March 2013, Eshelter-CCCM Cluster Fact sheet Vallée = 385 camps de Jacmel Bainet Jacmel WASH: According to the latest data from the DTM made in March 2013: Number of IDPs and camps under . 30% of displaced families living in camps with an organization forced eviction 2012 2013 dedicated to the management of the site . 88% of displaced households have latrines/toilets in camps. 9% of displaced households have access to safe drinking water within the camps. = 73,000 individuals . 23% of displaced households have showers in the camps. (21,000 households) Source : DTM_Report_March 2013 = 105 camps of 385 are at risk of forced eviction Health: Malnutrition According to the 2012-2013 nutrition report screening of FONDEFH in 7 camps in the metropolitan area with a population of 1675 children and 1,269 pregnant women: Number of IDPs and camps from 2010 Number of IDPs . -

Learning from Feed the Future Programs About Gender Integration and Women's Empowerment

Learning from Feed the Future Programs about Gender Integration and Women’s Empowerment COMPILED CASE SUBMISSIONS APRIL 2016 Learning from Feed the Future Programs about Gender Integration and Women’s Empowerment Compiled Case Submissions April 2016 The case studies in the following pages were solicited from Feed the Future partners through a Call for Cases about Feed the Future Learning on Gender Integration and Women’s Empowerment, released in April 2016.1 Feed the Future partners submitted twenty cases spanning ten different countries. The cases were ranked and chosen according to the quality of the data, the compelling nature of the story, demonstration of learning, and diversity of representation in terms of geography and type of intervention. While the majority of information in the Cultivating Women’s Empowerment: Stories from Feed the Future 2011-2015 came from these twenty cases, it was not possible to include everything. In the spirit of learning and transparency, all of the original case submissions are compiled here and are available for download on USAID’s Agrilinks website. They are a complimentary piece to the publication and showcase the broader set of activities happening around gender integration and women’s empowerment in Feed the Future programs. The cases are organized alphabetically by region and by country. 1 See the Call for Cases here: https://agrilinks.org/blog/call-cases-feed-future-programs-learning- gender-integration-and-women%E2%80%99s-empowerment. Table of Contents Asia 1 Bangladesh 1. Cereals Systems Initiative for South Asia in Bangladesh (CSISA-BD), submitted by CIMMYT 2 Latin America and the Caribbean 4 Haiti 2. -

The Contribution of Un Women to Increasing Women's

THEMATIC EVALUATION THE CONTRIBUTION OF UN WOMEN TO INCREASING WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP AND PARTICIPATION IN PEACE AND SECURITY AND IN HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE Final Synthesis Report September 2013 ©2013 UN Women. All rights reserved. Acknowledgements Produced by the Evaluation Office of UN Women A number of people contributed to the evaluation report. The evaluation was conducted by the Overseas Evaluation Team Development Institute, an independent external firm. Overseas Development Institute The evaluation was led by Pilar Domingo and sup- Pilar Domingo, Team Leader ported by a large team including Tam O’Neil and Marta Marta Foresti, Senior Evaluation Expert Foresti, amongst others. The UN Women Evaluation Tam O’Neil, Governance Expert Office team included Florencia Tateossian and Inga Karen Barnes, Gender Equality Expert Sniukaite. The evaluation benefitted from the active Ashley Jackson, Country Study Lead Researcher participation of country and headquarters reference Irina Mosel, Country Study Lead Researcher groups comprised of UN Women staff and manage- Leni Wild, Country Study Lead Researcher ment. UN Women country-level evaluation focal points Jill Wood, Research Assistant and Representatives ensured the country visits went Ardiana Gashi, Country Expert smoothly. The external reference group, comprised of Claud Michel Gerve, Country Expert key United Nations entities, provided valuable feed- Veronica Hinestroza, Country Expert back in the early stages. This evaluation would not have been possible without Evaluation Task Manager: Florencia Tateossian the support and involvement of stakeholders, ben- UN Women Evaluation Office eficiaries and partners at the national, regional and Editor: Michelle Weston global level. We extend thanks to all those who pro- Layout: Scott Lewis vided feedback which helped to ensure the evaluation Cover Photo: UN Photo/ Martine Perret reflects a broad range of views. -

")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un

HAITI: 1:900,000 Map No: ADM 012 Stock No: M9K0ADMV0712HAT22R Edition: 2 30' 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W N o r d O u e s t N " 0 Haiti: Administrative & MINUSTAH Regional Offices ' 0 La Tortue ! ° 0 N 2 " (! 0 ' A t l a n t i c O c e a n 0 ° 0 2 Port de Paix \ Saint Louis du Nord !( BED & Department Capital UN ! )"(!\ (! Paroli !(! Commune Capital (!! ! ! Chansolme (! ! Anse-a-Foleur N ( " Regional Offices 0 UN Le Borgne ' 0 " ! 5 ) ! ° N Jean Rabel " ! (! ( 9 1 0 ' 0 5 ° Mole St Nicolas Bas Limbe 9 International Boundary 1 (!! N o r d O u e s t (!! (!! Department Boundary Bassin Bleu UN Cap Haitian Port Margot!! )"!\ Commune Boundary ( ( Quartier Morin ! N Commune Section Boundary Limbe(! ! ! Fort Liberte " (! Caracol 0 (! ' ! Plaine 0 Bombardopolis ! ! 4 Pilate ° N (! ! ! " ! ( UN ( ! ! Acul du Nord du Nord (! 9 1 0 Primary Road Terrier Rouge ' (! (! \ Baie de Henne Gros Morne Limonade 0 )"(! ! 4 ! ° (! (! 9 Palo Blanco 1 Secondary Road Anse Rouge N o r d ! ! ! Grande ! (! (! (! ! Riviere (! Ferrier ! Milot (! Trou du Nord Perennial River ! (! ! du Nord (! La Branle (!Plaisance ! !! Terre Neuve (! ( Intermittent River Sainte Suzanne (!! Los Arroyos Perches Ouanaminte (!! N Lake ! Dondon ! " 0 (! (! ' ! 0 (! 3 ° N " Marmelade 9 1 0 ! ' 0 Ernnery (!Santiag o \ 3 ! (! ° (! ! Bahon N o r d E s t de la Cruz 9 (! 1 ! LOMA DE UN Gonaives Capotille(! )" ! Vallieres!! CABRERA (!\ (! Saint Raphael ( \ ! Mont -

Check out the Newsletter Online

MADRESpring/Summer 2010 www.madre.org speaks Stories of our Sisters 2010 www.madre.org b Spring/Summer 2010 b 1 From the Executive Director ViVian StrombErg Dear Friends, We launched the year with an urgent response to the catastrophic earthquake in Haiti. We MADRE used your support to bring life-saving medicines and supplies to survivors and to raise a call for Demanding Rights, human rights to be the guiding principles of relief efforts. Resources & Results for Women Worldwide As always, we made sure that your contributions not only provided humanitarian aid, 121 West 27th Street, # 301 but strengthened local women’s organizations, leaving skills and resources in the hands of New York, NY 10001 community members. We asked tough questions about how and Telephone: (212) 627-0444 Fax: (212) 675-3704 why Haitians were made so vulnerable to this disaster, recognizing e-mail: [email protected] that Haiti was devastated long before the earthquake of January 12. www.madre.org Board of Directors In fact, Haiti was devastated by some of the very policies that the Anne H. Hess US and other powerful actors now seek to accelerate in the name of Dr. Zala Highsmith-Taylor reconstruction. These policies have prioritized foreign investment Laura Flanders Linda Flores-Rodríguez over Haitians’ basic human rights. Holly Maguigan Margaret Ratner ©Harold Levine The women of our sister organizations don’t just want to see Haiti Marie Saint Cyr Pam Spees rebuilt; they want to see it transformed. They have a vision of another country grounded in human rights and environmental sustainability. -

Sex, Family & Fertility in Haiti

Sex, Family & Fertility in Haiti by Timothy T. Schwartz ***** First published in Hardback in 2008 by Lexington Books as, “Fewer Men, More Babies: Sex, family and fertility in Haiti. All Rights Reserved. Scholars, students, and critics may use excerpts as long as they cite the source. 2nd Edition published January 2011 ISBN 10 146812966X ISBN 13 9781468129663 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction Fertility .................................................................................................... 13 Table 1.1: Total fertility rates in Haiti (TFR) ........................................................................... 13 Kinship and Family Patterns ..................................................................................................... 14 NGOs and Paradigmatic Shift of Anthropology ....................................................................... 15 Jean Rabel and the Sociocultural Fertility Complex ................................................................. 15 The Research ............................................................................................................................. 17 The Baseline Survey ............................................................................................................. 17 The Opinion Survey .............................................................................................................. 18 Household Labor Demands Survey ...................................................................................... 18 Livestock and Garden Survey -

Haiti Study Abroad 2018 Water, Environmental Issues, and Service Learning May 20 (19 in GR) to June 19

Haiti Study Abroad 2018 Water, Environmental Issues, and Service Learning May 20 (19 in GR) to June 19 May 19th 4-6 pm - Pizza, Packing, and Parents party in Niemeyer MPR. Delta Air Lines 1369 20MAY Grand Rapids / Atlanta 8:10A 10:04A Delta Air Lines 685 20MAY Atlanta / PAP 11:20A-2:32P Delta Air Lines 684 19JUN PAP / Atlanta 3:30P-6:45P Delta Air Lines 1433 19JUN Atlanta / Grand Rapids 9:44P-11:43P OVERVIEW: • Saturday May 19, 4:00-6:00 pm Pizza, Packing, and Parent party Niemeyer Multipurpose Room, parents and friends invited. • Sunday, May 20th 6:00 am meet at Gerald R. Ford (GRR) Airport in Grand Rapids • Sunday, May 20th 8:10 am depart on Delta Flight DL 1369 • May 20th to May 23rd Staying at the Le Plaza Hotel, Port-au-Prince. • May 24th to May 26th Trip to Jacmel staying at Amitie Hotel. • May 27th travel to Deschapelles via PAP and airport stop at Moulin sur Mer museum en- route. • May 27 to June 10 Staying at HAS in Deschapelles, Haiti • June 11 to June 13 at UCI in Central Plateau (Pignon) • June 14 to June 18 in Cap Haitian at Auberge du Picolet Hotel • June 18 travel to PAP and stay at Servotel in Port au Prince • June 19 return flight to GRR FOR EMERGENCY CONTACT: Dr. Peter Wampler, Director ([email protected]): (US) (616) 638-2043 (cell) or (616) 331-2834 (office message) or +509 _____________ (Haiti Cell phone) Kelly McDonell, Assistant Director ([email protected]): (US) 248-459-4063 or (616) 331-8155 (office message) or +509 __________________ (Haiti Cell phone) Elena Selezneva (Padnos International Center) 616-331-3898 Rachel Fort (Hôpital Albert Schweitzer) + 509 3424-0465 (Haiti) [email protected] Leah Steele (Hôpital Albert Schweitzer) + 509 3735-8012 (Haiti) [email protected] Mahamat Koutami Adoum (HAS) + 509 3418-0700 (Haiti) [email protected] US Embassy Duty Officer in Haiti: +509 2229-8000 Boulevard du 15 October Tabarre 41, Route de Tabarre Port au Prince, Haiti Page 1 of 8 Daily Itinerary (subject to change as conditions warrant): Date Activity Contact Saturday, May 19 Pizza, packing, and Dr. -

Haitian Women's Role in Sexual Decision-Making: the Gap Between AIDS Knowledge and Behavior Change

FAMILY HEALTH INTERNATIONAL WORKING PAPERS Haitian Women's Role in Sexual Decision-Making: The Gap Between AIDS Knowledge and Behavior Change Priscilla R. Ulin, Ph.D. Michel Cayemittes, M.D. Elisabeth Metellus IJ1mm November 1995 ~J ...I'ZIZDZl No. WP95-04 AIDSCAP '11111' . ft Haitian Women's Role in Sexual Decision-Making: The Gap Between AIDS Knowledge and Behavior Change Priscilla R. Ulin, Ph.D. Family Health International, Research Triangle Park, NC Michel Cayemittes, M.D. Elisabeth Metellus Institut Haitien de l'Enfance, Petion Ville, Haiti Family Health International is a nonprofit research and technical assistance organization dedicated to contraceptive development, family planning, reproductive health and AIDS prevention around the world. Partial support for this study was provided by the AIDSCAP Department of Family Health International (FHI) with funds from the Uoited States Agency for International Development (USAID). The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of FHI or USAID. Data from this working paper, part of PHI's Working Paper Series, may not be cited or quoted without permission from Family Health International. © Family Health International, 1995 No. WP95-Q4 HAITIAN WOMEN'S ROLE IN SEXUAL DECISION-MAKING: THE GAP BETWEEN AIDS KNOWLEDGE AND BEHAVIOR CHANGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i I. Background 1.1 Introduction , 1 1.2 Research Problem and Objectives 4 1.3 The Focus Group Method 5 1.4 Research Procedures 6 1.4.1 Site Selection 6 1.4.2 Field Team ........................... .. 7 1.4.3 Data Collection 8 1.5 Data Analysis .. .............................. .. 11 1.6 Validity of the Data 12 II. Presentation of Findings 2.1 Introduction to the Findings 12 2.2 Causes of AIDS: Knowledge of Transmission 15 2.3 Women's Beliefs about Vulnerability ...............