The Current Situation and Use of Pottery in Myanmar Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Chindwin District Volume A

BURMA GAZETTEER LOWER CHINDWIN DISTRICT UPPER BURMA RANGOON OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, BURMA TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE PART A. THE DISTRICT 1-211 Chapter I. Physical Description 1-20 Boundaries 1 The culturable portion 2 Rivers: the Chindwin; the Mu 3 The Alaungdaw gorge 4 Lakes ib. Diversity of the district ib. Area 5: Surveys ib. Geology 6 Petroliferous areas ib. Black-soil areas; red soils ib. Volcanic rocks 7 Explosion craters ib. Artesian wells 8 Saline efflorescence ib. Rainfall and climate 9 Fauna: quadrupeds; reptiles and lizards; game birds; predatory birds 9-15 Hunting: indigenous methods 16 Game fish 17 Hunting superstitions 18 Chapter II, History and Archæology 20-28 Early history 20 History after the Annexation of 1885 (a) east of the Chindwin; (b) west of the Chindwin: the southern portion; (c) the northern portion; (d) along the Chindwin 21-24 Archæology 24-28 The Register of Taya 25 CONTENTS. PAGE The Alaungdaw Katthapa shrine 25 The Powindaung caves 26 Pagodas ib. Inscriptions 27 Folk-lore: the Bodawgyi legend ib. Chapter III. The People 28-63 The main stock 28 Traces of admixture of other races ib. Population by census: densities; preponderance of females 29-32 Towns and large villages 32 Social and religious life: Buddhism and sects 33-35 The English Wesleyan Mission; Roman Catholics 35 Animism: the Alôn and Zidaw festivals 36 Caste 37 Standard of living: average agricultural income; the food of the people; the house; clothing; expenditure on works of public utility; agricultural stock 38-42 Agricultural indebtedness 42 Land values: sale and mortgage 48 Alienations to non-agriculturists 50 Indigence 51 Wages ib. -

Flood Inundated Area in Monywa, Salingyi, Chaung-U and Myaung Townships, Sagaing Region

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Myanmar Information Management Unit ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Flood Inundated Area! in Monywa, Salingyi, Chaung-U and Myaung Townships, Sagaing Region ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (as of 20 July 2017, 6:15 AM) ! ! ! ! ! Ma Yoe Taw (South) ! ! ! Pauk Nge Taw ! Twin Chaung ! Hpan Khar Kyin Kyee Pa Don Nyaung Pin Hla Kan Hpyu (East) Kyoe Kyar Kan 95°15'E ! 95°30'E ! ! Thit Seint Pin Ywar Thit ! Kyauk Pyauk (Myauk Kone) ! ! ! ! Yin Ma Kan ! ! Budalin ! Ohn Pin Thar ! Thit Seint Pin ! ! 22°15'N 22°15'N ! ! U Thar Pon Kaing (East) Yae Oe Sin Dan Pin Te Ywar Thit Thar Yar Su Data Sources Ngwe Twin ! ! ! ! ! U Thar Pon Kaing (West) ! Hpa Yar Gyi Shar Pyay Tha Pyay Taw ! Htan Pin Hla ! ! Yae Kan Gyi Dan Pin Te Kyauk Pyauk ! ! ! Thar Si Kan Swei Chan Thar ! ! Tone Tin Kan ! Min Te ! ! Satellite Image: Sentinel 1A, 2017 ! ! Koe Pin Son Kone ! Pa Lin Kone ! Taung Yoe Hpar Aung Taw Zee Taw ! ! ! Kyun Ywar Thit ! Shar Pauk Taw ! Moe Kaung Than Po ! ! Kan Oh ! Image © Copyright: ESA Copernicus ! ! Kha Wea Kyin ! ! ! Ma Gyi Kone Te Gyi Kone ! Myit Nar Kaing ! ! Ywar Thar Kaing Yin Pan ! Ywar Thar War Pyit Ma (North) ! ! In Taing ! Say Thu ! Si Pin Thar ! ! Te Gyi Kone (West) ! ! / ! ! Man Da Lar War Pyit Ma (South) Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2017 ! ! Nwar Ma Thin (West) Sone Chaung (North) ! ! Kyun Hpo Pin ! ! ! Nyaung Chay Htauk Kaw La Pya ! ! Khoe Than Taung Yeik Thar ! Nwar Ma Thin (East) ! Sone -

AROUND MANDALAY You Cansnoopaboutpottery Factories

© Lonely Planet Publications 276 Around Mandalay What puts Mandalay on most travellers’ maps looms outside its doors – former capitals with battered stupas and palace walls lost in palm-rimmed rice fields where locals scoot by in slow-moving horse carts. Most of it is easy day-trip potential. In Amarapura, for-hire rowboats drift by a three-quarter-mile teak-pole bridge used by hundreds of monks and fishers carrying their day’s catch home. At the canal-made island capital of Inwa (Ava), a flatbed ferry then a horse cart leads visitors to a handful of ancient sites surrounded by village life. In Mingun – a boat ride up the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) from Mandalay – steps lead up a battered stupa more massive than any other…and yet only a AROUND MANDALAY third finished. At one of Myanmar’s most religious destinations, Sagaing’s temple-studded hills offer room to explore, space to meditate and views of the Ayeyarwady. Further out of town, northwest of Mandalay in Sagaing District, are a couple of towns – real ones, the kind where wide-eyed locals sometimes slip into approving laughter at your mere presence – that require overnight stays. Four hours west of Mandalay, Monywa is near a carnivalesque pagoda and hundreds of cave temples carved from a buddha-shaped moun- tain; further east, Shwebo is further off the travelways, a stupa-filled town where Myanmar’s last dynasty kicked off; nearby is Kyaukmyaung, a riverside town devoted to pottery, where you can snoop about pottery factories. HIGHLIGHTS Join the monk parade crossing the world’s longest -

Myanmar (Burma)

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Myanmar (Burma) Northern Myanmar p271 Mandalay & Around p234 Western ^# Myanmar Bagan & Eastern p307 Central Myanmar Myanmar p196 p141 Southwestern Myanmar ^# Yangon p86 p34 Southeastern Myanmar p105 Simon Richmond, David Eimer, Adam Karlin, Nick Ray, Regis St Louis PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Myanmar . 4 YANGON . 34 Myeik . 131 Myanmar Map . 6 Myeik (Mergui) Archipelago . 135 Myanmar’s Top 10 . .8 SOUTHWESTERN Kawthoung . 138 MYANMAR . 86 Need to Know . 14 Thanlyin & Kyauktan . 87 What’s New . 16 BAGAN & CENTRAL Bago . 88 MYANMAR . 141 If You Like… . 17 Pathein . .. 94 Yangon–Mandalay Month by Month . 19 Chaung Tha Beach . .. 99 Highway . 143 Ngwe Saung Beach . 102 Itineraries . 21 Taungoo (Toungoo) . 143 Nay Pyi Taw . 146 Before You Go . 23 SOUTHEASTERN Meiktila . 149 Regions at a Glance . 30 MYANMAR . 105 Yangon–Bagan Mon State . 107 Highway . 151 2P2PLAY / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / 2P2PLAY Mt Kyaiktiyo Pyay . 151 (Golden Rock) . 107 Thayekhittaya Mawlamyine . 109 (Sri Ksetra) . 154 Around Mawlamyine . 116 Magwe . 155 Ye . 119 Bagan . 156 Kayin State . 121 Nyaung U . 158 Hpa-an . 121 Old Bagan . 164 Around Hpa-an . 124 Myinkaba . 167 Myawaddy . 126 New Bagan (Bagan Myothit) . 167 Tanintharyi Region . 127 Around Bagan . 172 STREET FOOD AT BOGYOKE AUNG Dawei . 127 SAN MARKET P54, YANGON CHANTAL DE BRUIJNE / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / BRUIJNE DE CHANTAL SHWE YAUNGHWE KYAUNG P197, NYAUNGSHWE Contents UNDERSTAND Mt Popa . 172 Mingun . 269 Myanmar Salay . 173 Paleik . 270 Today . 336 Pakokku . 175 History . 338 Monywa . 176 NORTHERN People & Religious Around Monywa . 178 MYANMAR . 271 Beliefs of Myanmar . 352 Mandalay to Lashio . 273 Aung San Suu Kyi . -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Myanmar: Sagaing/Mandalay earthquake Situation Report No. 3 This report is produced by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Coordinator. It covers the period from 13 to 16 November 2012. Highlights • The Government indicates at least 16 people were killed and 52 other injured in the earthquake, registering 6.8 on the Richter scale that struck Sagaing and Mandalay Regions on 11 November. Unofficial reports suggest the number of casualties and injured may be higher. • The Government reports that over 400 houses, 65 schools and 100 religious buildings were damaged. • Out of 22 Townships affected across Sagaing and Mandalay Regions, initial information indicates that Singu and Thabeikkyin Townships in Mandalay and Kyaukmyaung sub-township in Sagaing were most affected. • The Government at Union and Region level has been the first responder. The UN Humanitarian Co-ordinator has been in regular contact with the Government to offer assistance of the international humanitarian community should this be needed. • An inter-agency rapid assessment team, comprising CARE, Save the Children, UNICEF and the Myanmar Nurses and Midwife Association, has been undertaking assessments across four townships, including Singu, Shwebo, Kyauk Myaung and Thabeikkyin, since 13 November. Myanmar Red Cross Society (MRCS) deployed three emergency response teams for assessments in the affected villages in Singu Township. • Needs identified preliminarily include temporary schools, and temporary shelters and non-food items for the families whose houses were destroyed in the earthquake. 16 52 400 65 22 deaths injuries houses schools townships destroyed damaged affected Situation Overview At least 16 people were killed and 52 injured, according to the Government as of 16 November, in the earthquake of 6.8 on the Richter scale in Sagaing and Mandalay Regions on 11 November, also causing damages to public buildings, residential houses and infrastructures. -

India-Myanmar-Bangladesh Border Region

MyanmarInform ationManage mUnit e nt India-Myanmar-Banglade shBord eRegion r April2021 92°E 94°E 96°E Digboi TaipiDuidam Marghe rita Bom dLa i ARUN ACHALPRADESH N orthLakhimpur Pansaung ARUN ACHAL Itanagar PRADESH Khonsa Sibsagar N anyun Jorhat INDIA Mon DonHee CHINA Naga BANGLA Tezpur DESH Self-Administered Golaghat Mangaldai Zone Mokokc hung LAOS N awgong(nagaon) Tuensang Lahe ASSAM THAILAND Z unhe boto ParHtanKway 26° N 26° Hojai Dimapur N 26° Hkamti N AGALAN D Kachin Lumd ing Kohima State Me huri ChindwinRiver Jowai INDIA LayShi Maram SumMaRar MEGHALAYA Mahur Kalapahar MoWaing Lut Karimganj Hom alin Silchar Imphal Sagaing ShwePyi Aye Region Kalaura MAN IPUR Rengte Kakc hing Myothit Banmauk MawLu Churachandpur Paungbyin Indaw Katha Thianship Tamu TRIPURA Pinlebu 24° N 24° W untho N 24° Cikha Khampat Kawlin Tigyaing Aizawal Tonzang Mawlaik Rihkhawdar Legend Ted im Kyunhla State/RegionCapital Serc hhip Town Khaikam Kalewa Kanbalu Ge neralHospital MIZORAM Kale W e bula TownshipHospital Taze Z e eKone Bord eCrossing r Falam Lunglei Mingin AirTransport Facility Y e -U Khin-U Thantlang Airport Tabayin Rangamati Hakha Shwebo TownshipBoundary SaingPyin KyaukMyaung State/RegionBoundary Saiha Kani BANGLA Budalin W e tlet BoundaryInternational Ayadaw MajorRoad Hnaring Surkhua DESH Sec ondaryRoad Y inmarbin Monywa Railway Keranirhat SarTaung Rezua Salingyi Chaung-U Map ID: MIMU1718v01 22° N 22° Pale Myinmu N 22° Lalengpi Sagaing Prod uctionApril62021 Date: Chin PapeSize r A4 : Projec tion/Datum:GCS/WGS84 Chiringa State Myaung SourcData Departme e : ofMe nt dService ical s, Kaladan River Kaladan TheHumanitarian ExchangeData Matupi Magway BasemMIMU ap: PlaceName General s: Adm inistrationDepartme (GAD)and field nt Cox'sBazar Region sourcTransliteration e s. -

STATUS and CONSERVATION of FRESHWATER POPULATIONS of IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D

WORKING PAPER NO. 31 MAY 2007 STATUS AND CONSERVATION OF FRESHWATER POPULATIONS OF IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D. Smith, Robert G. Shore and Alvin Lopez WORKING PAPER NO. 31 MAY 2007 sTATUS AND CONSERVATION OF FRESHWATER POPULATIONS OF IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D. Smith, Robert G. Shore and Alvin Lopez WCS Working Papers: ISSN 1530-4426 Copies of the WCS Working Papers are available at http://www.wcs.org/science Cover photographs by: Isabel Beasley (top, Mekong), Danielle Kreb (middle, Mahakam), Brian D. Smith (bottom, Ayeyarwady) Copyright: The contents of this paper are the sole property of the authors and cannot be reproduced without permission of the authors. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) saves wildlife and wild lands around the world. We do this through science, conservation, education, and the man- agement of the world's largest system of urban wildlife parks, led by the flag- ship Bronx Zoo. Together, these activities inspire people to imagine wildlife and humans living together sustainably. WCS believes that this work is essential to the integrity of life on earth. Over the past century, WCS has grown and diversified to include four zoos, an aquarium, over 100 field conservation projects, local and international educa- tion programs, and a wildlife health program. To amplify this dispersed con- servation knowledge, the WCS Institute was established as an internal “think tank” to coordinate WCS expertise for specific conservation opportunities and to analyze conservation and academic trends that provide opportunities to fur- ther conservation effectiveness. The Institute disseminates WCS' conservation work via papers and workshops, adding value to WCS' discoveries and experi- ence by sharing them with partner organizations, policy-makers, and the pub- lic. -

Tour Itinerary, Including 3 Domestic Flights

979 West Painted Clouds Place, Oro Valley, AZ 85755 www.handson.travel • [email protected] • 520-720-0886 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • MYANMAR APRIL 10 – 23, 2020 14 DAYS Be inspired by the monasteries, pagodas and stupas in Bago, Mingun, Amarapura and Mandalay. Cross the Gok Teik Viaduct on train. Take a stroll through countryside villages. Visit markets and workshops. Walk over a hundred year old teak U-Bein Bridge. Take on river cruises on Dotawaddy and Irrawaddy Rivers. Bicycle amongst the pagodas and stupas in Bagan. Observe the leg-rowing fishermen of Inle Lake. Ride on the Yangon Circular Railway. B – breakfast, L – lunch, D – dinner APRIL 10 • • • Upon arrival, you will be greeted by your guide. Before reaching the hotel to have a short walk about 15 minutes in to see the street life and night life of Yangon. Then you will transfer to your hotel. Welcome dinner. Stay in Yangon for 2 nights. D APRIL 11 • • • 2 hour drive to Bago, formerly known as Pegu. Capital of the Mon Kingdom in the 15th century. Visit Kyaly Khat Wai Monastery during lunch time. Shwethalyaung, the 180 foot long reclining Buddha. The Mon style Shwemawdaw Pagoda, one of the most venerated in Myanmar. Hintha Gon Paya. Kanbawzathadi Palace. Kyaik Pun Pagoda with 4 sitting Buddhas. On way back to Yangon, we stop at the Allied War Cemetery near Htaukkyan, the final resting place for over 27,000 allied soldiers who fought in Burma. B,L,D APRIL 12 • • • Morning flight to Mandalay, then drive about 2 hours to Pyin Oo Lwin, a former British hill station. -

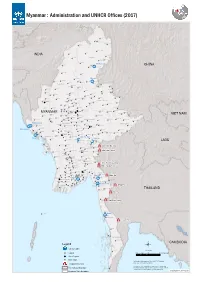

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe -

Rifles Regimental Road

THE RIFLES CHRONOLOGY 1685-2012 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 2 - CONTENTS 5 Foreword 7 Design 9 The Rifles Representative Battle Honours 13 1685-1756: The Raising of the first Regiments in 1685 to the Reorganisation of the Army 1751-1756 21 1757-1791: The Seven Years War, the American War of Independence and the Affiliation of Regiments to Counties in 1782 31 1792-1815: The French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 51 1816-1881: Imperial Expansion, the First Afghan War, the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, the Formation of the Volunteer Force and Childers’ Reforms of 1881 81 1882-1913: Imperial Consolidation, the Second Boer War and Haldane’s Reforms 1906-1912 93 1914-1918: The First World War 129 1919-1938: The Inter-War Years and Mechanisation 133 1939-1945: The Second World War 153 1946-1988: The End of Empire and the Cold War 165 1989-2007: Post Cold War Conflict 171 2007 to Date: The Rifles First Years Annex A: The Rifles Family Tree Annex B: The Timeline Map 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 3 - 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 4 - FOREWORD by The Colonel Commandant Lieutenant General Sir Nick Carter KCB CBE DSO The formation of The Rifles in 2007 brought together the histories of the thirty-five antecedent regiments, the four forming regiments, with those of our territorials. -

Sagaing Region - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SAGAING REGION - MYANMAR Nawngmun 93°30'E 94°0'E 94°30'E 95°0'E 95°30'E 96°0'E 96°30'E 97°0'E 97°30'E Putao Airport Puta-O Machanbaw Bhutan Pansaung India China Bangladesh Vietnam Nanyun Laos Nanyun 27°0'N 27°0'N Thailand Don Hee Cambodia Shin Bway Yang Sumprabum 26°30'N 26°30'N Lahe Tanai Lahe Htan Par Khamti Hkamti Airport 26°0'N INDIA Kway 26°0'N Injangyang Hkamti Hpakan Kamaing KACHIN 25°30'N Lay Shi Myitkyina 25°30'N Airport Lay Shi Nampong Sadung Air Base Myitkyina Waingmaw Mogaung LAKE Mo Paing INDAWGYI Lut 25°0'N Hopin 25°0'N Homalin Homalin Airport Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo Shwe Pyi Aye Dawthponeyan Myothit Banmauk Myo Hla 24°30'N CHINA 24°30'N Banmauk Katha Indaw Bamaw Tamu SAGAING Airport Paungbyin Momauk Bhamo Tamu Shwegu Lwegel Paungbyin Indaw Katha Mansi Pinlebu Pinlebu Muse Wuntho Manhlyoe 24°0'N (Manhero)24°0'N Cikha Wuntho Namhkan Kawlin Khampat Kawlin Tigyaing Tigyaing Mawlaik Mawlaik Tonzang Kyunhla Takaung Mabein 23°30'N 23°30'N Thabeikkyin Tedim Rihkhawdar Kalewa Kyunhla Manton Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Kanbalu Kalaymyo Airport Mingin Mongmit Kale Namtu Taze Lashio Namhsan 23°0'N Taze Airport Lashio23°0'N Falam Mogoke Mingin Thabeikkyin Mogoke Ye-U Khin-U Monglon Ye-U Khin-U Mongngawt Thantlang Tabayin Hakha Tabayin Shwebo Kyauk Hsipaw Myaung SHAN Shwebo Singu Kyaukme Singu Kani 22°30'N CHIN 22°30'N Kani Budalin Ayadaw Wetlet Budalin Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Monywa Madaya Airport Monywa Gangaw Madaya Yinmabin Monywa Yinmabin MANDALAY Rezua Mandalay Sagaing Patheingyi Pyinoolwin Pale City Salingyi