2015: Volume 27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ongoing & Upcoming Events

Country Pond Fish & Game Club - Newton, NH Established 1903 April 2021 www.cpfgc.com Volume 21-04 Ongoing & Upcoming Events APRIL CALENDAR (Unless otherwise indicated, all events and activities are Open to the Public) Indoor Work Parties Granite State Bowhunters Mondays, 18:00 - 20:00 Tournament Sunday, 11 April, 07:00 Indoor Archery League (CPF&G Club Members Only) New Member Orientation Tuesdays thru 13 April, 18:00 Sunday, 11 April, 10:00 (This Class is Full) Centerfire Pistol League Centerfire Pistol “Practice Plates” (CPF&G Club Members Only) Wednesdays, 3 February thru March, 17:00 (CPF&G Club Members Only) Tuesday, 13 April, 17:00 Trap Shooting Monthly Members Meeting Saturdays @ 13:00 & Sundays @ 09:00 Thursday, 15 April, 19:00 Your attendance would be appreciated. “Ladies Only” NRA Basic Pistol Shooting Course Centerfire Pistol Plate Shoot Saturday, 20 March, 08:00 Sunday, 18 April, 09:00 Centerfire Pistol Plate Shoot Sunday, 21 March, 09:00 Centerfire Pin Shoot Thursday, 22 April, 19:00 Centerfire Pin Shoot 3-Gun Thursday, 25 March, 19:00 Action Shooting Match Sunday, 25 April, 09:00 Centerfire Pistol “Practice Plates” Saturday, 27 March, 09:00 (CPF&G Club Members Only) Tuesday, 27 April, 17:00 Board of Directors Meeting Board of Directors Meeting Thursday, 1 April, 19:00 Thursday, 6 May, 19:00 Centerfire Pin Shoot NRA Basic Pistol Shooting Course Thursday, 8 April, 19:00 Saturday, 8 May, 08:00 April 2021 Trigger Times page 2 RANGE CLOSURES thru April (Hours shown are ACTUAL TIMES CLOSED) OUTDOOR RANGE INDOOR PISTOL RANGE Sunday, 21 MAR .................... -

PERUTA; MICHELLE No

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT EDWARD PERUTA; MICHELLE No. 10-56971 LAXSON; JAMES DODD; LESLIE BUNCHER, DR.; MARK CLEARY; D.C. No. CALIFORNIA RIFLE AND PISTOL 3:09-cv-02371- ASSOCIATION FOUNDATION, IEG-BGS Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO; WILLIAM D. GORE, individually and in his capacity as Sheriff, Defendants-Appellees, STATE OF CALIFORNIA, Intervenor. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of California Irma E. Gonzalez, Senior District Judge, Presiding 2 PERUTA V. CTY. OF SAN DIEGO ADAM RICHARDS; SECOND No. 11-16255 AMENDMENT FOUNDATION; CALGUNS FOUNDATION, INC.; BRETT D.C. No. STEWART, 2:09-cv-01235- Plaintiffs-Appellants, MCE-DAD v. OPINION ED PRIETO; COUNTY OF YOLO, Defendants-Appellees. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of California Morrison C. England, Chief District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted En Banc June 16, 2015 San Francisco, California Filed June 9, 2016 Before: Sidney R. Thomas, Chief Judge and Harry Pregerson, Barry G. Silverman, Susan P. Graber, M. Margaret McKeown, William A. Fletcher, Richard A. Paez, Consuelo M. Callahan, Carlos T. Bea, N. Randy Smith and John B. Owens, Circuit Judges. Opinion by Judge W. Fletcher; Concurrence by Judge Graber; Dissent by Judge Callahan; Dissent by Judge Silverman; Dissent by Judge N.R. Smith PERUTA V. CTY. OF SAN DIEGO 3 SUMMARY* Civil Rights The en banc court affirmed the district courts’ judgments and held that there is no Second Amendment right for members of the general public to carry concealed firearms in public. -

State RKBA Websites. Last Updated: 3/23/2020 These Sites Are Listed Here As a Convenience to Our Readers

State RKBA Websites. Last Updated: 3/23/2020 These sites are listed here as a convenience to our readers. Handgunlaw.us in no way endorses Connecticut Indiana any websites or is responsible for their content. Indiana St Rifle & Pistol Association We will not list just chat forums on this page CT Citizens Defense League The 2nd Amendment Patriots Connecticut Carry Alabama Iowa Bama Carry Delaware Iowa Firearms Coalition DE State Sportsmen's Association Iowa Gun Owners Alaska Delaware Open Carry Alaska Outdoor Council Kansas Florida Kansas State Rifle Association Am. Samoa Floridacarry.org 2nd Amendment Coalition of Florida Kentucky Arizona KY Coalition to Carry Concealed Arizona Citizens Defense League Georgia Arizona State Rifle & Pistol Assn. GeorgiaCarry.org Louisiana GeorgiaPacking.org Arkansas Georgia Gun Owners Maine California Guam Maine Gun Owners Association California Rifle & Pistol Association Gun Owners of Maine Golden State 2nd Amendment Council Hawaii Gun Owners of California Hawaii Firearms Coalition Maryland California Gun Rights Foundation Hawaii Rifle Association Maryland Shall Issue CAL-FFL Firearms Policy Coalition Idaho Massachusetts Idaho 2nd Amendment Alliance Gun Owners Action League Lawful & Responsible Gun Owners Colorado Illinois Commonwealth 2A Colorado State Shooting Association Illinois State Rifle Association Pikes Peak Firearms Coalition Illinois Carry Michigan Rocky Mountain Gun Owners Guns Save Life MCRGO Michigan Rifle & Pistol Association Michigan Open Carry Michigan Gun Owners www.handgunlaw.us 1 Minnesota New Mexico Puerto Rico Gun Owners Civil Rights Alliance New Mexico Shooting Sports Assoc. Gun Rights & Safety Association MN Gun Owners Caucus New York Rhode Island Mississippi SAFE RI Firearms Owner's League MS St Firearm Owners Association SCOPE RI 2nd Amendment Coalition NY State Rifle & Pistol Association Missouri South Carolina MO Sport Shooting Assn. -

The Grassroots Action Guide for Ohio Gun Owners.Qxd

Buckeye Firearms Association The Grassroots Action Guide for Ohio Gun Owners Page 1 — 5-Minute Handbook for Grassroots Activists Page 6 — How to Be an Effective Volunteer Page 8 — 15 Ways to Fight for Our Second Amendment Rights Page 15 — Become 500 Times More Powerful Politically Page 20 — Gun Rights Are About More Than Guns Page 22 — A Psychiatrist Examines The Anti-Gun Mentality Page 1 5-Minute Handbook for Grassroots Activists Adapted from an essay circulating the Internet — author unknown I’ve been a gun rights activist for nearly 10 years. I wasted a lot of time for the first 5 years because no one gave me the rule book you are now reading. Maybe that’s because no one had written it. This is the stuff I wish I had known starting on Day One. The next 5 minutes you spend reading this might save you 5 years of other- wise wasted time and energy. If you’ve been in the gun rights game for a while, this handbook will be the fastest refresher course you’ve ever taken. This past year I’ve received a lot of mail from jittery gun owners who are finally waking up to what’s happening to our right to keep and bear arms(RKBA). This handbook is mostly for them. If the rules I list below scare off a few folks, so be it. I want to tell it like it really is to give a quick snapshot of the tips, tricks and tactics that actually work in RKBA activism. The bad news is that this is not a complete list of the rules. -

Guns, Democracy, and the Insurrectionist Idea

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE GUNS, DEMOCRACY, AND THE INSURRECTIONIST IDEA GUNS, DEMOCRACY, AND THE INSURRECTIONIST IDEA Joshua Horwitz and Casey Anderson the university of michigan press ann arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2009 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2012 2011 2010 2009 4 3 2 1 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Horwitz, Joshua, 1963– Guns, democracy, and the insurrectionist idea / Joshua Horwitz and Casey Anderson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-472-11572-3 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-472-11572-3 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-472-03370-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-472-03370-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Civil rights—United States. 2. Gun control—United States. 3. Firearms—Law and legislation—United -

Fight for Freedom

33rd Annual GUN RIGHTS POLICY CONFERENCE FIGHT FOR FREEDOM September 21-23, 2018 • Chicago, IL Co-Sponsoring Organizations CITIZENS COMMITTEE SECOND FOR THE RIGHT TO KEEP AMENDMENT AND BEAR ARMS FOUNDATION Official GRPC Radio Station: WIND 560 AM – The Answer Funding Sources American Legacy Firearms KeepAndBearArms.com Ammo.Com Merril Press Armed American Radio Microsoft© Gun Club CrossBreed Holsters Henry Repeating Rifles Delta Defense Heroes and Patriots Firearms Dillon Precision SCCY Firearms Glock TheGunMag.com Gun Talk Radio U S Law Shield IAPCAR U.S. Concealed Carry Association Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership Women & Guns Magazine Participating Organizations and Entities: A Girl and a Gun Shooting League • Accuracy in Media • Accuracy in Academia • American Political Action Committee • Ammoland.com • Arizona Citizens Defense League • Arizona Rifle & Pistol Association • Armed American Radio • Arms Room Radio • Association of New Jersey Rifle & Pistol Clubs • AZFirearms.com • Black Guns Matter • Bloomfield Press • Breitbart.com • Buckeye Firearms Association • Cal-FFL • CalGuns Foundation • Cato • Chicago Guns Matter • Coloradans for Civil Liberties • Commonwealth 2A • Crime Prevention Research Center • Defense Small Arms Advisory Council • Doctors for Responsible Gun Ownership • EyeOnTheTargetRadio.com • FASTER Colorado • ForeFront • Firearms Coalition • Firearms Policy Coalition • Firearms United Global • Florida Rifle & Pistol Association • Florida Carry, Inc. • Florida Shooting Sports Association • FrontSightPress.com • GeorgiaCarry.org • Golden State Second Amendment Council • Gottlieb-Tartaro Report • Grassroots North Carolina • Gun Freedom Radio • Gun Owners Action League (Massachusetts) • Gun Owners Action League of Washington • Gun Owners of America • Guns Save Life • Gun Freedom Radio • Guns.com • Hawaii State Rifle and Pistol Association • The Heartland Institute • Heroes and Patriots Firearms • Human Events • I.C.E. -

Decl. of Alexandra Robert Gordon (2:17-Cv-00903-WBS-KJN) Exhibit 55

1 XAVIER BECERRA, State Bar No. 118517 Attorney General of California 2 TAMAR PACHTER, State Bar No. 146083 Supervising Deputy Attorney General 3 ALEXANDRA ROBERT GORDON, State Bar No. 207650 JOHN D. ECHEVERRIA, State Bar No. 268843 4 Deputy Attorneys General 455 Golden Gate Avenue, Suite 11000 5 San Francisco, CA 94102-7004 Telephone: (415) 703-5509 6 Fax: (415) 703-5480 E-mail: [email protected] 7 Attorneys for Defendants 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 12 13 WILLIAM WIESE, et al., 2:17-cv-00903-WBS-KJN 14 Plaintiff, EXHIBITS 55 THROUGH 64 TO THE DECLARATION OF ALEXANDRA 15 v. ROBERT GORDON IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF’S MOTION FOR 16 TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER XAVIER BECERRA, et al., AND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 17 Defendant. Date: June 16, 2017 18 Time: 10:00 a.m. Courtroom: 5 19 Judge: The Honorable William B. Shubb Action Filed: April 28, 2017 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Decl. of Alexandra Robert Gordon (2:17-cv-00903-WBS-KJN) Exhibit 55 Gordon Declaration 01879 Written Testimony for Chief Jim Bueermann (Ret.) President, Police Foundation, Washington, D.C. Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing on Gun-related Violence Wednesday, January 30, 2013 I write to you in my capacity as both President of the Police Foundation and the former Chief of Police of the Redlands, CA Police Department. The Police Foundation, established in 1970 by the Ford Foundation, is a non-partisan, non-constituency research organization. Our mission is to advance policing through innovation and scientific research. -

GT July 2016

Second Amendment Foundation ISSN 1079-6169 The G ottlieb TR artaro eport t THE INSIDERS GUIDE FOR GUN OWNERS Issue 259 July, 2016 Dear Subscriber, PRESIDENT OBAMA called the shooting at Orlandoís Pulse gay nightclub by Islamic jihadist OMAR MIR SEDDIQUE MATEEN “a further reminder of how easy it is for someone to get their hands on a weapon that lets them shoot people in a school, or a house of worship, or a movie theater, or a nightclub.” OBAMA would not say ìIslamistî despite MATEENís widely known pledge of allegiance to radical ISIL on a 911 call during his attack. OBAMA described the shooting as an attack on a place of solidarity and empowerment and reiterated a need for stricter gun laws, AT THE saying, “To actively do nothing is a decision as well,” but didnít elaborate on the changes he would like to see. FEDERAL A day later, OBAMA escalated his call that dangerous LEVEL people not be allowed to obtain high-powered weapons, saying the country needs more "soul-searching" after MATEEN used legally purchased firearms to kill 49 people at the Pulse. OBAMA said the attack was an example of "home-grown extremism" that wasn't carried out at the specific direction of ISIS. While OBAMA vowed to go after extremist groups that have called for attacks on Americans, he also renewed his failed push for laws making it harder for criminals – and the law abiding – to obtain firearms. Senate Democrats urged quick passage of legislation defeated last year to impose additional gun controls in the wake of the Pulse shooting. -

On Gun Registration, the NRA, Adolf Hitler, and Nazi Gun Laws: Exploding the Gun Culture Wars (A Call to Historians)

Fordham Law Review Volume 73 Issue 2 Article 11 2004 On Gun Registration, the NRA, Adolf Hitler, and Nazi Gun Laws: Exploding the Gun Culture Wars (A Call to Historians) Bernard E. Harcourt Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Recommended Citation Bernard E. Harcourt, On Gun Registration, the NRA, Adolf Hitler, and Nazi Gun Laws: Exploding the Gun Culture Wars (A Call to Historians), 73 Fordham L. Rev. 653 (2004). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol73/iss2/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On Gun Registration, the NRA, Adolf Hitler, and Nazi Gun Laws: Exploding the Gun Culture Wars (A Call to Historians) Cover Page Footnote Professor of Law, University of Chicago. Special thanks to Saul Cornell, Martha Nussbaum, and Richard Posner for conversations and comments; and to Kate Levine and Aaron Simowitz for excellent research assistance. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol73/iss2/11 CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES ON GUN REGISTRATION, THE NRA, ADOLF HITLER, AND NAZI GUN LAWS: EXPLODING THE GUN CULTURE WARS (A CALL TO HISTORIANS) Bernard E. Harcourt* INTRODUCTION Say the words "gun registration" to many Americans-especially pro-gun Americans, including the 3.5 million-plus members of the National Rifle Association ("NRA")-and you are likely to hear about Adolf Hitler, Nazi gun laws, gun confiscation, and the Holocaust. -

Ongoing & Upcoming Events

Country Pond Fish & Game Club - Newton, NH Established 1903 July 2021 www.cpfgc.com Volume 21-07 Ongoing & Upcoming Events JULY CALENDAR (Unless otherwise indicated, all events and activities are Open to the Public) Indoor Work Parties New Member Orientation Sunday, 11 July, 10:00 Mondays, 18:00 - 20:00 (By Appointment Only) Rifle League Centerfire Pistol “Practice Plates” Mondays thru September (CPF&G Club Members Only) 18:00 Tuesday, 13 July, 17:00 Trap Shooting Tuesdays thru September @ 17:00 Monthly Members Meeting Saturdays @ 13:00 & Sundays @ 09:00 Thursday, 15 July, 19:00 Your attendance would be appreciated. Rockingham County Trap League Steel Plate Shoot Wednesdays, thru 30 June, 17:00 Sunday, 18 July, 09:00 CMP Semi-Auto Shoot Saturday, 19 June, 10:00 Centerfire Pin Shoot Centerfire Pistol “Practice Plates” Thursday, 22 July, 19:00 (CPF&G Club Members Only) Wednesday, 22 June, 17:00 Steel Challenge Saturday, 24 July, 09:00 Centerfire Pin Shoot Thursday, 24 June, 19:00 CMP Bolt-Action Shoot Saturday, 25 July, 10:00 3-Gun Action Shooting Match Centerfire Pistol “Practice Plates” Saturday, 26 June, 12:00 (CPF&G Club Members Only) thru Sunday, 27 June, 18:00 Tuesday, 27 July, 17:00 Board of Directors Meeting Thursday, 1 July, 19:00 Board of Directors Meeting Thursday, 5 August, 19:00 Centerfire Pin Shoot Steel Plate Shoot Thursday, 8 July, 19:00 Sunday, 8 August, 09:00 As an NRA affiliated club, it is important for us to support the National Rifle Association. By joining the NRA through CPF&G Club, $5 of the annual fee, or $10 of the 3-yr membership fee, is paid back to our club. -

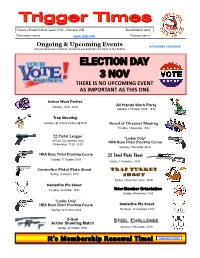

Election Day 3 Nov There Is No Upcoming Event As Important As This One

Country Pond Fish & Game Club - Newton, NH Established 1903 November 2020 www.cpfgc.com Volume 20-11 Ongoing & Upcoming Events NOVEMBER CALENDAR (Unless otherwise indicated, all events and activities are Open to the Public) ELECTION DAY 3 NOV THERE IS NO UPCOMING EVENT AS IMPORTANT AS THIS ONE Indoor Work Parties Mondays, 18:00 - 20:00 All Hands Work Party Saturday, 31 October, 08:00 - 16:00 Trap Shooting Saturdays @ 13:00 & Sundays @ 09:00 Board of Directors Meeting Thursday, 5 November, 19:00 22 Pistol League “Ladies Only” (CPF&G Club Members Only) NRA Basic Pistol Shooting Course Wednesdays, 17:30 - 20:00 Saturday, 7 November, 08:00 NRA Basic Pistol Shooting Course .22 Steel Plate Shoot Saturday, 17 October, 08:00 Sunday, 8 November, 09:00 Centerfire Pistol Plate Shoot TRAP Turkey Sunday, 18 October, 09:00 Shoot Sunday, 8 November, 09:00 - 15:00 Centerfire Pin Shoot Thursday, 22 October, 19:00 New Member Orientation Sunday, 8 November, 10:00 “Ladies Only” NRA Basic Pistol Shooting Course Centerfire Pin Shoot Saturday, 24 October, 08:00 Thursdays, 12 November, 19:00 3-Gun Action Shooting Match Sunday, 25 October, 09:00 Saturday, 14 November, 09:00 It’s Membership Renewal Time! RENEWAL FORM November 2020 Trigger Times page 2 RANGE CLOSURES NOVEMBER thru November (Hours shown are ACTUAL TIMES CLOSED) CALENDAR INDOOR PISTOL RANGE OUTDOOR RANGE Mondays .................................. 18:00 - 20:00 Sunday, 18 OCT ...................... 09:00 - 13:30 Indoor Work Parties Centerfire Pistol Plate Shoot Wednesdays ............................ 17:00 - 20:00 Monday, 19 OCT ..................... 09:00 - 14:00 TRAP RANGE Rimfire Pistol League Wednesday, 21 OCT .............. -

Allegheny County Sportsmen's League Legislative Committee Report

Allegheny County Sportsmen’s League Legislative Committee Report April 2008 Issue 162 ALLEGHENY COUNTY SPORTSMEN LEAGUE ON THE INTERNET http://www.acslpa.org Contacts : Legislative Committee Chairman , Kim Stolfer (412.221.3346) - [email protected] Legislative Committee Vice-Chairman, Mike Christeson - [email protected] Leading off the Rally was guest speaker Alan Keyes Philadelphia Council and Mayor Pass with host legislator Rep. Daryl Metcalfe guiding the rally. O ther featured speakers at today’s rally included Larry Pratt , and Sign Into Law Illegal Gun executive director, Gun Owners of America; Alan Gottlieb , Control Bills chairman, Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear (April 10 th ) Just moments ago at 3PM Philadelphia Arms; Jeff Knox , director of operations, Firearms Coalition; Mayor Nutter signed into law five ordinances passed by Kim Stolfer , chairman, Firearms Owners Against Crime; Melody Zullinger , executive director, PA Federation of City Council in ‘violation’ of Pennsylvania law. These Sportsmen’s Clubs, and Jon Mirowitz , Unified Sportsmen of measures cover the following concepts: Pennsylvania. 1. limit handgun purchases to one a month In attendance were over 500 gun owners from all 2. require lost or stolen firearms to be reported to police points of the state and many grassroots groups including: within 24 hours 3. forbid individuals under protection from abuse orders Allegheny County Sportsmen’s League, CCRKBA, from possessing guns if ordered by the court GunWeek, Jews for the Preservation of Firearms 4. allow removal of firearms from "persons posing a risk Ownership, Law Enforcement Alliance of America, Lehigh of imminent personal injury" to themselves or others, as Valley Firearms Coalition, Mothers Arms - Safely in determined by a judge Mothers Arms Inc., National Rifle Association, National 5.