Infestus Tutamen (Aggressive Protection)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

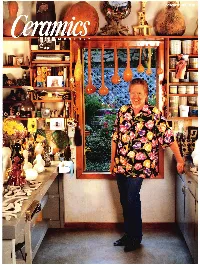

Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics

A Ceramics Monthly Handbook Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics: Defining Twentieth Century Ceramics A Collection of Articles from Ceramics Monthly Edited by Elaine M. Levin Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics: Defining Twentieth Century Ceramics Movers & Shakers in American Ceramics: Defining Twentieth Century Ceramics A Collection of Articles from Ceramics Monthly Edited by Elaine M. Levin Published by The American Ceramic Society 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, Ohio 43082 USA The American Ceramic Society 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210 Westerville, OH 43082 © 2003, 2011 by The American Ceramic Society, All rights reserved. ISBN: 1-57498-165-X (Paperback) ISBN: 978-1-57498-560-3 (PDF) No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in review. Authorization to photocopy for internal or personal use beyond the limits of Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law is granted by The American Ceramic Society, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 U.S.A., www.copyright.com. Prior to photocopying items for educational classroom use, please contact Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. This consent does not extend to copyright items for general distribution or for advertising or promotional purposes or to republishing items in whole or in part in any work in any format. Requests for special photocopying permission and reprint requests should be directed to Director, Publications, The American Ceramic Society, 600 N. -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition in Modern Japanese Ceramics of the Postwar Period Comparison of a Vase by Hamada Shōji and a Jar by Kitaōji Rosanjin Grant Akiyama Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2017 Grant Akiyama, BS Dr. Hope Marie Childers, Thesis Advisor Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the patience and wisdom of my advisor, Dr. Hope Marie Childers. I thank Dr. Meghen Jones for her insights and expertise; her class on East Asian crafts rekindled my interest in studying Japanese ceramics. Additionally, I am grateful to the entire Division of Art History. I thank Dr. Mary McInnes for the rigorous and unique classroom experience. I thank Dr. Kate Dimitrova for her precision and introduction to art historical methods and theories. I thank Dr. Gerar Edizel for our thought-provoking conversations. I extend gratitude to the libraries at Alfred University and the collections at the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum. They were invaluable resources in this research. I thank the Curator of Collections and Director of Research, Susan Kowalczyk, for access to the museum’s collections and records. I thank family and friends for the support and encouragement they provided these past five years at Alfred University. I could not have made it without them. Following the 1950s, Hamada and Rosanjin were pivotal figures in the discourse of American and Japanese ceramics. -

Earthenware Clays

Arbuckle Earthenware Earthenware Clays Earthenware usually means a porous clay body maturing between cone 06 – cone 01 (1873°F ‐ 2152°F). Absorption varies generally between 5% ‐20%. Earthenware clay is usually not fired to vitrification (a hard, dense, glassy, non‐absorbent state ‐ cf. porcelain). This means pieces with crazed glaze may seep liquids. Terra sigillata applied to the foot helps decrease absorption and reduce delayed crazing. Low fire fluxes melt over a shorter range than high fire materials, and firing an earthenware body to near vitrification usually results in a dense, brittle body with poor thermal shock resistance and increased warping and dunting potential. Although it is possible to fire terra cotta in a gas kiln in oxidation, this is often difficult to control. Reduced areas may be less absorbent than the rest of the body and cause problems in glazing. Most lowfire ware is fired in electric kilns. Gail Kendall, Tureen, handbuilt Raku firing and bodies are special cases. A less dense body has better thermal shock resistance and will insulate better. Earthenware generally shrinks less than stoneware and porcelain, and as a result is often used for sculpture. See Etruscan full‐size figure sculpture and sarcophagi in terra cotta. At low temperatures, glaze may look superficial & generally lacks the depth and richness of high fire glazes. The trade‐offs are: • a brighter palette and an extended range of color. Many commercial stains burn out before cone 10 or are fugitive in reduction. • accessible technology. Small electric test kilns may be able to plug into ordinary 115 volt outlets, bigger kilns usually require 208 or 220 volt service (the type required by many air conditioners and electric dryers). -

Adrian Saxe by Elaine Levin

October 1993 1 William Hunt.................................... Editor Ruth C. Butler ................Associate Editor Robert L. Creager..................... Art Director Kim Nagorski..... .............Assistant Editor Mary Rushley ............... Circulation Manager Mary E. Beaver ....Assistant Circulation Manager Connie Belcher .......Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis .......................... Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard Post Office Box 12448 Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 FAX (614) 488-4561 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0328) is pub lished monthly except July and August by Profes sional Publications, Inc., 1609 Northwest Bou levard, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second Class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates: One year $22, two years $40, three years $55. Add $10 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. In Canada, also add GST (registration number R123994618). Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send the magazine address label as well as your new address to: Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Offices, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, announcements, news releases, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (including 35mm slides), graphic illustrations and digital TIFF or EPS im ages are welcome and will be considered for publication. Mail submissions to Ceramics Monthly, Post Office Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. We also accept unillustrated mate rials faxed to (614) 488-4561. Writing and Photographic Guidelines:A book let describing standards and procedures for sub mitting materials is available upon request. Indexing:An index of each year’s articles appears in the December issue. Additionally, Ceramics Monthly articles are indexed in the Art Index. Printed, on-line and CD-ROM (computer) index ing is available through Wilsonline, 950 Univer sity Avenue, Bronx, New York 10452; and from Information Access Company, 362 Lakeside Drive, Forest City, California 94404. -

Postmodernism

Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 1 Black Black POSTMODERNISM STYLE AND SUBVERSION, 1970–1990 TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 Edited by Glenn Adamson and Jane Pavitt V&A Publishing TJ254-3-2011 IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm 175L 130 Stora Enso M/A Magenta(V) 130 Stora Enso M/A 175L IMUK VLX0270 Postmodernism W:247mmXH:287mm TJ254-3-2011 2 3 Black Black Exhibition supporters Published to accompany the exhibition Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970 –1990 Founded in 1976, the Friends of the V&A encourage, foster, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London assist and promote the charitable work and activities of 24 September 2011 – 15 January 2012 the Victoria and Albert Museum. Our constantly growing membership now numbers 27,000, and we are delighted that the success of the Friends has enabled us to support First published by V&A Publishing, 2011 Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970–1990. Victoria and Albert Museum South Kensington Lady Vaizey of Greenwich CBE London SW7 2RL Chairman of the Friends of the V&A www.vandabooks.com Distributed in North America by Harry N. Abrams Inc., New York The exhibition is also supported by © The Board of Trustees of the Victoria and Albert Museum, 2011 The moral right of the authors has been asserted. -

Nmservis Nceca 2015

nce lournal 'Volume37 lllllllIt { t t \ \ t lr tJ. I nceoqKAlt$[$ 5OthAnnual Conference of the NationalCouncilon C0'LECTURE:INNOVATIONS lN CALIFORNIACIAY NancyM. Servis and fohn Toki Introduction of urbanbuildings-first with architecturalterra cotta and then Manythink cerar.nichistory in theSan Francisco Bay Area with Art Decotile. beganin 1959with PeterVoulkos's appointrnent to theUniversi- California'sdiverse history served as the foundationfor ty of California-Berkeley;or with Funkartist, Robert Arneson, its unfolding cultural pluralisrn.Mexico claimed territory whosework at Universityof California-Davisredefined fine art throughlarge land grants given to retiredmilitary officersin rnores.Their transfonnative contributions stand, though the his- themid l9th century.Current cities and regions are namesakes tory requiresfurther inquiry. Califbr- of Spanishexplorers. Missionaries nia proffereda uniqueenvironr.nent arriving fronr Mexico broughtthe through geography,cultural influx, culture of adobe and Spanishtile and societalflair. cleatingopportu- with ther.n.Overland travelers rni- nity fbr experirnentationthat achieved gratedwest in pursuitof wealthand broadexpression in theceralnic arts. oppoltunity,including those warrtilrg Today,artistic clay use in Cali- to establishEuropean-style potteries. forniais extensive.lts modernhistory Workersfrorn China rnined and built beganwith the l9th centurydiscov- railroads,indicative of California's ery of largeclay deposits in the Cen- directconnection to PacificRirn cul- tral Valley, near Sacramento.This -

Ceramics Monthly William C

2 Ceramics Monthly William C. Hunt........................................ Editor Barbara Tipton...................... Associate Editor Robert L. Creager........................ Art Director Ruth C. Butler.............................. Copy Editor Valentina Rojo....................... Editorial Assistant Mary Rushley .............. Circulation Manager Connie Belcher .... Advertising Manager Spencer L. Davis.............................. Publisher Editorial, Advertising and Circulation Offices 1609 Northwest Boulevard, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212 (614) 488-8236 Ceramics Monthly (ISSN 0009-0329) is published monthly except July and August by Professional Publications, Inc.—S. L. Davis, Pres.; P. S. Emery, Sec.: 1609 North west Blvd., Columbus, Ohio 43212. Second class postage paid at Columbus, Ohio. Subscription Rates:One year $16, two years $30, three years $40. Add $5 per year for subscriptions outside the U.S.A. Change of Address:Please give us four weeks advance notice. Send both the magazine wrapper label and your new address to Ceramics Monthly, Circulation Office, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Contributors: Manuscripts, photographs, color separations, color transparencies (in cluding 35mm slides), graphic illustrations, texts and news releases dealing with ceramic art are welcome and will be considered for publication. A booklet describing procedures for the preparation and submission of a man uscript is available upon request. Send man uscripts and correspondence about them to The Editor, Ceramics Monthly, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Indexing:Articles in each issue of Ceramics Monthly are indexed in the Art Index. A 20-year subject index (1953-1972) covering Ceramics Monthly feature articles, Sugges tions and Questions columns is available for $1.50, postpaid from the Ceramics Monthly Book Department, Box 12448, Columbus, Ohio 43212. Additionally, each year’s arti cles are indexed in the December issue. -

Craft Horizons AUGUST 1973

craft horizons AUGUST 1973 Clay World Meets in Canada Billanti Now Casts Brass Bronze- As well as gold, platinum, and silver. Objects up to 6W high and 4-1/2" in diameter can now be cast with our renown care and precision. Even small sculptures within these dimensions are accepted. As in all our work, we feel that fine jewelery designs represent the artist's creative effort. They deserve great care during the casting stage. Many museums, art institutes and commercial jewelers trust their wax patterns and models to us. They know our precision casting process compliments the artist's craftsmanship with superb accuracy of reproduction-a reproduction that virtually eliminates the risk of a design being harmed or even lost in the casting process. We invite you to send your items for price design quotations. Of course, all designs are held in strict Judith Brown confidence and will be returned or cast as you desire. 64 West 48th Street Billanti Casting Co., Inc. New York, N.Y. 10036 (212) 586-8553 GlassArt is the only magazine in the world devoted entirely to contem- porary blown and stained glass on an international professional level. In photographs and text of the highest quality, GlassArt features the work, technology, materials and ideas of the finest world-class artists working with glass. The magazine itself is an exciting collector's item, printed with the finest in inks on highest quality papers. GlassArt is published bi- monthly and divides its interests among current glass events, schools, studios and exhibitions in the United States and abroad. -

Fiamagazinemay–Aug 2016 1 2 from the Executive Director

Flint Institute of Arts fiamagazineMAy–AUG 2016 1 2 FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Website flintarts.org In 1928, the Flint Institute of Arts was arts students. Currently serving nearly Mailing Address 1120 E. Kearsley St. formed as an art school with the purchase 50 students from 15 school districts contents Flint, MI 48503 of the Flint School of Art and Design, at within the region, the main objective Telephone 810.234.1695 that time enrolling 150 students. Today, of this program is to further enhance the FIA Art School is ranked the sixth student abilities through advanced Fax 810.234.1692 from the director 2 largest in the nation according to the studio instruction, college admission Office Hours Mon–Fri, 9a–5p 2015 statistical survey conducted by the preparation, and exposure to various exhibitions 3–8 Gallery Hours Mon–Fri, 12p–5p Association of Art Museum Directors, an career paths within the arts. Over the video 9 Sat, 10a–5p; Sun, 1p–5p organization that comprises more than course of the three-year program, each Closed on major holidays 200 major art museums in North America. student produces a portfolio developed art on loan 10 Theater Hours Fri & Sat, 7:30p; Sun, 2p The Art School’s 16,000 to showcase his or her square feet facility hosts individual strengths for college Museum Shop 810.234.1695 donor profile 11 Mon–Sat, 10a–5p studio activities for a large and applications and scholarship Sun, 1p–5p diverse audience. Primarily consideration. serving the 1,500+ students The FIA engages in Healing acquisitions 12–14 The Palette 810.249.0593 Mon–Fri, 9a–5p enrolled in non-accredited Arts partnerships that promote calendar 15 & 23 Sat, 10a–5p; Sun, 1p–5p visual art courses, the FIA offers emotional and physical healing The Museum Shop and The instruction in drawing, painting, for patients undergoing films 16–18 Palette Café are open late welding, ceramics, printmaking, prolonged treatment as a result for select special events. -

From Rodin to Schütte

ART AND CERAMICS FROM RODIN TO SCHÜTTE SÈVRES – CITÉ DE LA CÉRAMIQUE March 9 – June 12, 2016 LA MAISON ROUGE, PARIS March 9 – June 5, 2016 Art and ceramics – CERAMIX – From Rodin to Schütte Exhibition: March 9 – June 12, 2016 (Sèvres – Cité de la céramique), March 9 – June 5, 2016 (La maison rouge) Content p. 2 – 3 Foreword Camille Morineau and Lucia Pesapane p. 5 – 15 Exhibition sections Camille Morineau and Lucia Pesapane p. 16 – 17 Information around the exhibition p. 18 – 30 Selected artworks p. 31 Visiting information p. 32 Partners p. 33 – 40 Appendix: Chronology Baimba Kamara Sèvres – Cité de la céramique La maison rouge Cultural development delegation Claudine Colin Communication Sylvie Perrin, head of communication and press relations Pénélope Ponchelet and Marine Le Bris tel. +33 (0)1 46 29 38 38 / cell.+33 (0)6 25 12 82 87 tel. + 33(0)1 42 72 60 01 [email protected] [email protected] ; [email protected] 2 CERAMIX ART AND CERAMICS FROM RODIN TO SCHÜTTE SÈVRES – CITÉ DE LA CÉRAMIQUE March 9 – June 12, 2016 LA MAISON ROUGE, PARIS March 9 – June 5, 2016 Preview: March 8, 2016 Press preview 9:15 a.m. to 11:15 a.m.: Sèvres – Cité de la céramique (8.45 a.m.: departure Palais Royal for Sèvres) 10:30 a.m. to 12:30 a.m.: La maison rouge (shuttle bus between Sèvres and Paris) Professionnal preview 17 p.m. to 21 p.m.: La maison rouge 18 p.m. to 23 p.m.: Sèvres – Cité de la céramique Cité de la Céramique in Sèvres, La maison rouge museum dedicated to ceramics from all over in Paris and the Bonnefantenmuseum in the world. -

American Ceramic Circle Fall Newsletter 2015 American Ceramic Circle Fall Newsletter 2015

AMERICAN Ceramic Circle FALL NEWSLETTER 2015 AMERICAN Ceramic Circle FALL NEWSLETTER 2015 OFFICERS OF THE AMERICAN CERAMIC CIRCLE 2015 Donna Corbin CONTENTS Chairman The American Ceramic Circle (ACC) was founded in 1970 as a Anne Forschler-Tarrasch ACC TRIP TO MEXICO 5 non-profit educational organization committed to the study and President appreciation of ceramics. Its purpose is to promote scholarship Adrienne Spinozzi GRANT AWARDS 6 Vice President and research in the history, use, and preservation of ceramics of Margaret Zimmermann GRANTS AND SCHOLARSHIPS 7 Secretary all kinds, periods, and origins. The current active membership of approximately five hundred is composed of museum professionals, M. L. Coolidge PUBLICATIONS 8 Treasurer collectors, institutions, and a limited number of dealers in ceramics. Suzanne Findlen Hood CERAMIC NOTES AND RESEARCH 9 Member interest is focused on post-Medieval pottery and porcelain Administrator Anne Forschler-Tarrasch EXHIBITIONS 14 of Europe, Asian ceramics of all periods, and ceramics made, used, Symposium Chair or owned in North America. Elizabeth Williams MUSEUM INSTALLATIONS 27 Grants Chair The ACC is chartered in the State of Maine as a 501 (c) 3 Corporation and is governed by a volunteer Board of Trustees. Dorothy Cobb CONFERENCES, SYMPOSIA, AND LECTURES 30 Development Chair Amanda Lange ANNOUNCEMENTS 32 Journal Editor David Conradsen, Adrienne Spinozzi NEW ACQUISITIONS 33 Newsletter Editors Shirley Mueller PRIVATE COLLECTIONS 36 Book Award Chair Angelika Kuettner UPCOMING FAIRS AND AUCTIONS 38 Website Coordinator Barbara McRitchie Archivist Thank you for all your contributions to this edition of the Newsletter. Cover Image: One of a pair of sample plates, Dutch (Delft), ca.