Unfaithful Reading in Modernist Undecidability Lucas H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macquarie University Alex Munt New Directions in Music Video: Vincent Moon and the 'Ascetic Aesthetic'

Munt New directions in music video Macquarie University Alex Munt New Directions in Music Video: Vincent Moon and the ‘ascetic aesthetic’ Abstract: This article takes the form of a case study on the work of French filmmaker and music video director Vincent Moon, and his ‘Takeaway Shows’ at the video podcast site La Blogothèque. This discussion examines the state, and status, of music video as a dynamic mode of convergent screen media today. It is argued that the recent shift of music video online represents a revival of music video—its form and aesthetics— together with a rejuvenation of music video scholarship. The emergence of the ‘ascetic aesthetic’ is offered as a new paradigm for music video far removed from that of the postmodern MTV model. In this context, new music video production intersects with notions of immediacy, authenticity and globalised film practice. Here, convergent music video is enabled by the network of Web 2.0 and facilitated by the trend towards amateur content, participatory media and Creative Commons licensing. The pedagogical implications of teaching new music video within screen media arts curricula is highlighted as a trajectory of this research. Biographical note: Alex Munt is a filmmaker and screen theorist. He is a Lecturer in the Department of Media, Music, Communication and Cultural Studies at Macquarie University. He recently completed a PhD on ‘Microbudget Digital Cinema’ and has published on topics that include digital filmmaking, screenwriting, music video, fashion and design media in Australian and UK media, journals and magazines. Keywords: Aesthetics – Music – Video – Vincent Moon 1 Broderick & Leahy (eds) TEXT Special Issue, ASPERA: New Screens, New Producers, New Learning, April 2011 Munt New directions in music video The focus of this article is the work of French filmmaker and music video director Mathieu Saura, more commonly known by his alias ‘Vincent Moon’. -

Documentary in the Steps of Trisha Brown, the Touching Before We Go And, in Honour of Festival Artist Rocio Molina, Flamenco, Flamenco

Barbican October highlights Transcender returns with its trademark mix of transcendental and hypnotic music from across the globe including shows by Midori Takada, Kayhan Kalhor with Rembrandt Trio, Susheela Raman with guitarist Sam Mills, and a response to the Indian declaration of Independence 70 years ago featuring Actress and Jack Barnett with Indian music producer Sandunes. Acclaimed American pianist Jeremy Denk starts his Milton Court Artist-in-Residence with a recital of Mozart’s late piano music and a three-part day of music celebrating the infinite variety of the variation form. Other concerts include Academy of Ancient Music performing Purcell’s King Arthur, Kid Creole & The Coconuts and Arto Lindsay, Wolfgang Voigt’s ambient project GAS, Gilberto Gil with Cortejo Afro and a screening of Shiraz: A Romance of India with live musical accompaniment by Anoushka Shankar. The Barbican presents Basquiat: Boom for Real, the first large-scale exhibition in the UK of the work of American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988).The exhibition brings together an outstanding selection of more than 100 works, many never seen before in the UK. The Grime and the Glamour: NYC 1976-90, a major season at Barbican Cinema, complements the exhibition and Too Young for What? - a day celebrating the spirit, energy and creativity of Basquiat - showcases a range of new work by young people from across east London and beyond. Barbican Art Gallery also presents Purple, a new immersive, six-channel video installation by British artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah for the Curve charting incremental shifts in climate change across the planet. -

Monika Brodka Poznaj Rafała, ERA NADAJE

ERA NADAJE listopad-styczeń 2010/2011 Magazyn trafia tylko do wybranych abonentów. Ty jesteś wśród nich! Monika Brodka Ekskluzywny wywiad STR. 8 Poznaj Rafała, który wystąpił w teledysku Katy Perry STR. 4 Pauline 1 Era Na da je Rytm muzyczny portret Re dak cja: Eryk Smól ski, Do ro ta An chim Kon takt: Pol ska Te le fo nia Cy fro wa Sp. z o.o. Al. Je ro zo lim skie 181, 02-222 War sza wa e‑ma il: [email protected], fax: (22) 413 69 14 Projekt i wykonanie: Novimedia Content Publishing Jej muzyki nie da się sklasyfikować. Jest mieszanką popu, Pra wo do błę dów w dru ku za strze żo ne. Ofer ta oraz ce ny mo gą ulec zmia nie. Szcze gó ły jazzu, rapu, gospel i soulu. Nic dziwnego, wychowała się w re gu la mi nach pro mo cji do stęp nych w punk tach sprze da ży i na stro nie www.era.pl. w rodzinie będącej miksem kultur. Okład ka fo to: Per Kristiansen ANNA GłOWACKA Jak się zaczęła Twoja przygoda z muzyką? Myślę, że lepiej spytać o to moją mamę, ale od kiedy pamiętam byłam szczęśliwa, śpiewając, grając, malując i tańcząc. Właściwie większosć mojej rodziny jest związana z muzyką lub sztuką w jakiś sposób. Kiedy zorientowałaś się, że chcesz wyrażać się przez muzykę? Nie myślałam o tym poważnie, póki nie skończyłam 19 lat i w moich rękach nie znalazł się kontrakt z wytwórnią Universal. Choć tak naprawdę, to nie muzykę miałam w planach. Chciałam pojechać do Portugalii, uczyć się języków, studiować i zostać scenarzystką. -

JACOB KIRKEGAARD B. 1975 Copenhagen Living in Germany Courtesy Galleri Tom Christoffersen Skindergade 5 1159 Copenhagen K Denmar

JACOB KIRKEGAARD B. 1975 Copenhagen Living in Germany Courtesy Galleri Tom Christoffersen Skindergade 5 1159 Copenhagen K Denmark T +45 33917610 M +45 26377210 [email protected] www.tomchristoffersen.dk EDUCATION 2006 MA at the Academy of Media Arts, Cologne, Germany. With prof.dr. Siegfried Zielinski & prof. Anthony Moore. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART. Retrospective solo exhibition. Roskilde, Denmark 2014 MORI ART MUSEUM. Comissioned work STIGMA. Tokyo, Japan 2013 COSMO CAIXA (Science Museum), LABYRINTHITIS, 16-channel installation in spiral staircase, Barcelona, Spain 2012 LEAP (Lab for Electronic Arts and Performance) PIVOT. Berlin, Germany, 2011 ESPACIO DE ARTE CONTEMPORANEO. PHANTOM BELL. Montevideo, Uruguay CHATEAU - CENTRO DE ARTE CONTEMPORANEO. Sound, video & photo works. Cordoba, Argentina DIAPASON GALLERY. Sound, video & photo works. New York City, USA 2010 KW – Kunstwerke. Sound installation HAUS DER MAHRE based on recordings of people sleeping. Berlin Germany 2009 HELENE NYBORG CONTEMPORARY. PHONURGIA METALLIS & NAGARAS # 1 & 2. Copenhagen, Denmark 2008 FUNDACION LUDWIG. AION. Havana, Cuba 2007 SWISS INSTITUTE. 32-channel installaton: BROADWAY. New York City, USA NATIONAL CENTRE OF CONTEMPORARY ART. THE VISITOR. Kaliningrad, Russia SKOLSKÁ 28 GALLERY. AION. Prague, Czech Republic 2006 GALLERY RACHEL HAFERKAMP. AION. Cologne, Germany DIAPASON GALLERY. AION. New York City, USA Skindergade 5 | 1159 København K | +45 33917610 / +45 26377210 | [email protected] | www.tomchristoffersen.dk GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2015 NAK – NEUER AACHENER KUNSTVEREIN. Untitled (Black Metal), Germany GIBCA – GOTHENBIRG BIENNIAL. Tristeleg # 1- 3 GALLERI TOM CHRISTOFFERSEN. Great Gifts of Chance. Copenhagen, DK 2014 MARRAKECH BIENNALE. The 24-channel sound installation freq_out. Teatre Royal. Morocco SCHWANKHALLE. Presenting the work MATTER of MEMORY at group show Oblivion, Berlin, Germany 2013 LOUISIANA – Museum of Modern Art, Commissioned new piece, ISFALD, for the exhibition: Arctic, Humlebæk, DK MoMA – Museum of Modern Art. -

Lower Res Sxsw Service Deck

Charlotte Von Kotze - Music Supervisor Quick Presentation SUMMARY + 10 years in the Music Industry (Music Supervision, Experiential Promoter, Endorsement) + 4 years of Music Supervision with multi formats Role • Currently Director of Music for our branded content and clients at VICE since 2014 with the support of two people; able to free up some time for side projects • My Creative and licensing expertise mixed with my wide music network allow me to provide the best music solutions with a fast turnaround and based on flexible budgets • Built strong interactions with the production landscapes: client, account, legal, talent, creative, producer, editor teams • Passionate and reputed for my proactive and relevant talent & music suggestions resulting from a worldwide and cross- genre music industry network (artists, composers, managers, labels, publishers) and fresh talents from the USA, Europe, South America, Africa • Very detail-oriented and rigorous regarding clearances and legal vetting; proactively find solutions and replacements. Music Supervision Formats & Contents • Range of mediums: Highly versatile and experienced with digital, broadcast, virtual reality and formats: commercials, branded content, trailers, films, documentaries, music videos • One feature documentary: “The Most Unknown” (2018) directed by Ian Cheney and distributed on Motherboard and “Moving Stories” (2018) directed by Robert Fruchman with a premiere during Doc Fortnight at Moma (2018). • Two Short Movies: “Hail Mary Country” (2017) with AFI and “Before the Bomb” (2015) -

N E X T W a V E F E St Iv a L O C T 2 01 8

OCT 2018 NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL NEXT WAVE Roy Lichtenstein, Reflections on Hair, 1990 Published by: Season Sponsor: 2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Oct 10 at 8pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda: The Ashram Experience Curated by Par Neiburger Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Support for female choreographers and composers in the Next Wave Festival provided by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Support for the Signature Artists Series provided by the Howard Gilman Foundation The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane ALICE COLTRANE TURIYASANGITANANDA, AN APPRECIATION Presented with Luaka Bop Alice Coltrane was an African American artist, mother, and spiritual leader who grew up playing gospel, classical, and jazz in Detroit. She was an exceptional musician who married John Coltrane and continued his spiritual quest. When John Coltrane died in 1967, it left his wife of only a few years bereft. After a time of great suffering, Alice met guru Swami Satchidananda and traveled to India with him. Following a visit there, she had a vision to open an ashram, and bought 50 acres of land in Agoura Hills, California, on the outskirts of Los Angeles. There a multi-ethnic and multi generational religious community grew up around her. The high point of living in this very special and loving environment took shape on Sundays when Alice would lead the community in a musical ceremony, mixing both gospel and Indian chant, to create a music she wholly invented. -

Corpus Antville

Corpus Epistemológico da Investigação Vídeos musicais referenciados pela comunidade Antville entre Junho de 2006 e Junho de 2011 no blogue homónimo www.videos.antville.org Data Título do post 01‐06‐2006 videos at multiple speeds? 01‐06‐2006 music videos based on cars? 01‐06‐2006 can anyone tell me videos with machine guns? 01‐06‐2006 Muse "Supermassive Black Hole" (Dir: Floria Sigismondi) 01‐06‐2006 Skye ‐ "What's Wrong With Me" 01‐06‐2006 Madison "Radiate". Directed by Erin Levendorf 01‐06‐2006 PANASONIC “SHARE THE AIR†VIDEO CONTEST 01‐06‐2006 Number of times 'panasonic' mentioned in last post 01‐06‐2006 Please Panasonic 01‐06‐2006 Paul Oakenfold "FASTER KILL FASTER PUSSYCAT" : Dir. Jake Nava 01‐06‐2006 Presets "Down Down Down" : Dir. Presets + Kim Greenway 01‐06‐2006 Lansing‐Dreiden "A Line You Can Cross" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 SnowPatrol "You're All I Have" : Dir. 01‐06‐2006 Wolfmother "White Unicorn" : Dir. Kris Moyes? 01‐06‐2006 Fiona Apple ‐ Across The Universe ‐ Director ‐ Paul Thomas Anderson. 02‐06‐2006 Ayumi Hamasaki ‐ Real Me ‐ Director: Ukon Kamimura 02‐06‐2006 They Might Be Giants ‐ "Dallas" d. Asterisk 02‐06‐2006 Bersuit Vergarabat "Sencillamente" 02‐06‐2006 Lily Allen ‐ LDN (epk promo) directed by Ben & Greg 02‐06‐2006 Jamie T 'Sheila' directed by Nima Nourizadeh 02‐06‐2006 Farben Lehre ''Terrorystan'', Director: Marek Gluziñski 02‐06‐2006 Chris And The Other Girls ‐ Lullaby (director: Christian Pitschl, camera: Federico Salvalaio) 02‐06‐2006 Megan Mullins ''Ain't What It Used To Be'' 02‐06‐2006 Mr. -

Universidade Tecnológica Federal Do Paraná Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Tecnologia

UNIVERSIDADE TECNOLÓGICA FEDERAL DO PARANÁ PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM TECNOLOGIA RAFAEL TOGO KUMOTO COLECIONANDO MÚSICAS COM UMA CÂMERA: MEDIAÇÕES AUDIOVISUAIS E HIPERMIDIÁTICAS NA PRODUÇÃO ARTÍSTICA DAS SESSIONS DO YOUTUBE DISSERTAÇÃO CURITIBA 2016 RAFAEL TOGO KUMOTO COLECIONANDO MÚSICAS COM UMA CÂMERA: MEDIAÇÕES AUDIOVISUAIS E HIPERMIDIÁTICAS NA PRODUÇÃO ARTÍSTICA DAS SESSIONS DO YOUTUBE Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Tecnologia da Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de “Mestre em Tecnologia” – Área de concentração: Tecnologia e Sociedade. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Luciana Martha Silveira CURITIBA 2016 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Kumoto, Rafael Togo K96p Colecionando músicas com uma câmera : mediações audiovi- 2016 suais e hipermidiáticas na produção artística das sessions do Youtube / Rafael Togo Kumoto.-- 2016. 213 f. : il. ; 30 cm. Texto em português, com resumo em inglês Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná. Programa de Pós-graduação em Tecnologia, Curitiba, 2016 Bibliografia: p. 185-206 1. YouTube (Recurso eletrônico). 2. Gravações de vídeo interativas. 3. Cantores. 4. Tecnologia - Dissertações. I. Silveira, Luciana Martha, orient. II. Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Tecnologia, inst. III. Título. CDD: Ed. 22 -- 600 Biblioteca Central da UTFPR, Câmpus Curitiba RESUMO KUMOTO, Rafael T. Colecionando músicas com uma câmera: mediações audiovisuais e hipermidiáticas na produção artística das sessions do YouTube. 2016. 213 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Tecnologia) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Tecnologia, Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná. Curitiba, 2016. Neste trabalho, buscamos analisar uma série de processos de mediação imagética, auditiva e hipermidiática na produção videográfica das sessions, compreendida enquanto circuito de publicações de coletivos cadastrados na plataforma do website YouTube. -

1 C's Videofest 2009 Chron Schedule Thursday, November

1 C's VideoFest 2009 Chron Schedule http://www.c-cyte.com/VideoFest_2009_Schedule.pdf via c-Blog at http://c-cyte.blogspot.com You can "build your own" at the VideoFest's site at http://www.videofest.org; I just find the chron format below easier to deal with. This schedule was hastily pasted together; apologies for any errors. I have not filled in the descriptions of all the individual videos in compilations, but sometimes randomly picked up one or two to get a feel for what they might be like. Yellow-highlighted items are rec'd because either I've seen them and liked them, I've seen and liked the artist's other work, or the piece happens to be in the area of one of my peculiar interests (so, no yellow does not mean it's not good). Comments in brackets are my own. All programs are at the Angelika Dallas – see you there! Thursday, November 5th 7:00 PM American Casino Leslie Cockburn Documentary | 89 min. It was a subprime mortgage gamble and the working-class were unwitting chips on the table. This debut feature gets to the guts of the matter by explaining how $8 trillion vanished into the American Casino. We hear from a teacher, a banker who sold us out, a mortgage salesman who inflated incomes to justify loans, and a billionaire who won a $500 million bet that people would lose their homes. We see the casinos endgame: Riverside, California a foreclosure wasteland of rats and meth labs, where mosquitoes breed in stagnant swimming pools of yesterday’s dreams. -

IFFNY 2015 Program

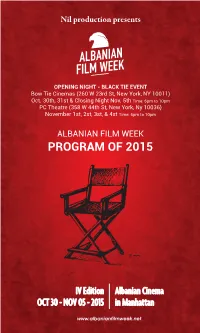

Nil production presents OPENING NIGHT - BLACK TIE EVENT Bow Tie Cinemas (260 W 23rd St, New York, NY 10011) Oct. 30th, 31st & Closing Night Nov. 5th Time: 6pm to 10pm PC Theatre (358 W 44th St, New York, Ny 10036) November 1st, 2st, 3st, & 4st Time: 6pm to 10pm ALBANIAN FILM WEEK PROGRAM OF 2015 IV Edition Albanian Cinema OCT 30 - NOV 05 - 2015 in Manhattan www.albanianfilmweek.net OPENING CEREMONY - The last battle / Alban Zogjani / short. 11’ Cast: Xhejlane Terbunja, Andi Bajgora,Bislim Mucaj, Maki OCTOBER. 30. 2015 – FRIDAY / Miftari, Besart Sllamniku, Rifat Smani, Blin Berisha. Bow Tie Cinemas, Room 7- 260 W 23rd St, New York, NY 10011 Synopsis: Linda, a thirty-year old widow takes care of her son who is passionate about the football team Real Madrid 6:30pm - Red Carpet Black Tie Event especially about Ronaldo. Ylli is sick. Real Madrid comes to play 8:00pm - Opening Ceremony / Introduction 20’ in Kosovo for its first time, of course Linda and Yll have bought 8:20pm - Three Windows And A Hanging / Isa Qosja / Feature film 1’34’’ the tickets but one day before the match something happens. Cast: Irena Cahani, Donat Qosja, Luan Jaha, Leonora Mehmetaj, Xhevat Qorraj. - Kali / Alban Ukaj & Yll Citaku/ Short film 14’ 20’’. Synopsis: In a traditional village in Kosova, a year after the war Cast: Izudin Bajroviç, Florist Bajgora, Ermal Gërdovci, Lum Berisha. when people rebuilding their lives, the female school teacher Synopsis: October 1st, 1997. Students turn out on the streets of Lushe is driven by her inner conscience to give an interview to Prishtina to protest for their rights, against the repressive regime. -

Du 22 Au 31 Octobre 2011 Vendôme(41)

Du 22 au 31 octobre 2011 Vendôme (41) 1 20e édition Conseillère générale de Loir-et-Cher Musiques, cinéma , conte, photographie, littérature, d'Avril à Décembre 7 festivals embellissent la vie des Vendômois et attirent plus de 80 000 spectateurs. édito La Communauté du Pays de Vendôme est fière d'être le premier partenaire e AVOIR 20 ANS DANS LES OREILLES de cette saison de festivals unique en Région Centre. 20 Il a deux types de festivals, ceux qui sous-estiment leur auditoire et ceux Catherine Lockhart, Maire de Vendôme, Présidente de la Communauté du Pays de Vendôme, qui le tiennent en haute estime. Ceux qui servent l’interchangeable soupe réchauffée, enflant comme des baudruches sponsorisées à mesure que l’ambition artistique perd du terrain et ceux qui n’ont pas oublié les raisons pour lesquelles ils ont décidé un jour de faire partager leurs frissons. Ceux qui font résonner la médiocrité ambiante et ceux qui la défient de s’approcher. Ceux qui programment du vide pourvu qu’ils fassent le plein et ceux qui changent les repères parce qu’ils voient encore la scène comme un lieu sacré. Ceux qui élèvent la curiosité, le partage, l’intelligence, l’art et la beauté au rang de manifeste, ceux-là sont les ennemis déclarés de notre système au bord de la salvatrice implosion. L’avenir qui se dessine aujourd’hui découlera directement de ceux-ci ou de ceux-là, dans quelque domaine que ce soit. Car ce système a beau mépriser les valeurs qui ne participent pas à son développement obscène, une lente révolte, douce et décidée, monte en mille lieux, amorcée par ceux qui ne se résignent pas, par les indignés espagnols, par ceux qui font un pas de côté et foncent, portés par le sens qu’ils mettent au coeur de tout ce qu’ils font. -

Curriculum Vitae: Tara X Aka Tara Transitory Aka One Man Nation Biography

Curriculum Vitae: Tara x aka Tara Transitory aka One Man Nation Biography “The woman who is gonna change your perception of electronic music forever, the modern shaman, the exorcist of our disenchanted age, the unique and wild” - Vincent Moon Tara Transitory (aliases - ne Man Nation " Tara_##x$ is a musician with a %ac&ground in media art' Graduating in )**+ with a Master in Media ,esign from the -iet .wart /nstitute in the Netherlands, her wor& focuses mainly on the dissolution of the self through performance and life as art itself' She currently splits his time %etween 1urope and Asia where she is co-directing The Unifiedfield artist-in- residence program and art space with Marta Moreno Mu4o5' Tara has collaborated in her existence with Pierre Bastien, C-drik Fermont, Truna, Machinefabrie&, Kato :ide&i, ,amo 0u5u&i, :ilary ;effrey, Shaun San&aran, <ichard Scott, 9atie ,uc&, Alfredo Genovesi, Soopa 7ollective, 6ambu Wu&ir, /man Zimbot and has performed internationally at festivals such as The Guggenheim Museum (6il%ao$, /012 (,ortmund), Mapping ((eneva), -iksel (6ergen$, M1M (6il%ao$, ST1/M Jamboree (Amsterdam), Makeart (-oitiers$, Fete 0'> ( rl?ans$ and Summer@26 (Gijon$' Education )**BC)**+ - Piet Zwart Institute (!@$ - Masters in Media Design & Communication: Networked Media >+++C)**) - Ngee Ann Polytechnic (Singapore$ - Technical Diploma in Film, Sound and Video Grants )*>) Apr - National Arts Council Presentations & Promotions Grant )*>> Mar - European Culture Foundation Step Beyond Grant )*>> Mar - Singapore Internationale Grant