Quinn P. Coffey Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Jewish-Christian Relations in the University Classroom

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 307 180 SO 019 860 AUTHOR Shermis, Michael, EC. TITLE Teaching Jewish-Christian Relations in the University Classroom. PUB DATE 88 NOTE 127p. 7UB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Shofar; v6 n4 Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Anti Semitism; Biblical Literature; Biographies; *Christianity; *Cultural Exchange; *Cultural Interrelationships; Educational Resources; Higher Education; *Judaism IDENTIFIERS Israel; Jewish Culture; *Jewish Studies; WiesP1 (Eli) ABSTRACT This special issue on "Teaching Jewish-Christian Relations in the University Classroom" is meaAt to be a resource for those involved in Jewish studies and who teach about Jewish-Christian relations. It offers an introduction to the topics of the Jewish-Christian encounter, Israel, anti-Semitism, Christian Scriptures, the works of Elie Wiesel, and available educational resources, all in light of the Jewish-Christian dialogue in institutions of higher learning. Carl Evans presents a syllabus for a course in which students are required to converse with local clergy in order to explain the Jewish-Christian dialogue at the grass-roots level. This technique helps students develop mature ways of thinking on a personal, social, and religious level. Robert Everett and Bruce Bramlett discuss Israel's problematic existence, raising numerous points that can lead to effective classroom discussions. Alan Davies describes his, course on anti-Semitism and presents several practical suggestions and instrumental techniques. John Roth offers a short biography of Elie Wiesel's J.ife, his writings, and his paradoxes. Norman Beck provides a model of how a Christian teaches the Christian Scriptures, offering guidelines that are highly supportive of and sympathetic to the Jewish-Christian dialogue. -

Cry for Hope, an Urgent Call to End the Oppression of the Palestinian People

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Global Coalition of Christians Issues Call for Palestinian Justice A growing list of church leaders and justice advocates sign on to the call Bethlehem, Palestine, July 1, 2020— Kairos Palestine and Global Kairos for Justice, a broad network of allies including Palestinian Christians and international friends of Kairos Palestine, issue Cry for Hope, an urgent call to end the oppression of the Palestinian people. Rifat Kassis, General Coordinator of Kairos Palestine, explains, “The Body of Christ can no longer stand by as world leaders and the international community trample on the rights of Palestinians to dignity, justice and self-determination under international law. The integrity of the Christian faith itself is at stake.” The authors of this international call describe the release as coming at a time of global emergencies, when the world has been summoned to turn its attention to the most vulnerable. They point to movements around the world that are seeking to bring down the structures of racism, ethnic cleansing, and the violation of land and its resources. Cry for Hope: A Call to Decisive Action makes the case that, as Israel announces its annexation plans, a critical point has been reached in the struggle to end the oppression of the Palestinians. Authors of the Cry for Hope argue that the personal, cultural, economic and environmental suffering of Palestinians under occupation increases day-by-day. Apart from the Cry, leaders around the world have made the case that, with expected support from the U.S. administration, Israel’s annexation of an additional one-third of the West Bank, including the fertile Jordan Valley, will effectively accomplish the goal of colonizing the Palestinian homeland. -

Concordis Papers Viii

CONCORDIS PAPERS VIII Christian Churches and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict February 2010 Third Edition 2 Blessed are the peacemakers … Matthew 5:9 List of Contents Page 3 Introduction Rt Hon Viscount Brentford 4 Maps 5 A Note on the Purpose of this Booklet (Revised for 3rd Edtion) 6 Chronology (expanded in 2nd Edition) 8 Current Political Background Dr Fiona McCallum 10 A Christian View of Israel Dr Calvin Smith 12 Biblical Perspectives on Israel and Palestine and how these Relate to the Church Revd Chris Rose 14 Summary of Discussion at Consultation 16 Working Together towards Peaceful Co‐existence Geoffrey Smith and Jerry Marshall 18 Musalaha and the Churches Dr Salim Munayer 20 The Need for a Bridging Narrative Dr Richard Harvey 22 Engaging with the Land and People Revd Mike Fuller 24 Core Christian Principle Common to All Ben White 26 The Contributors 27 About Concordis International Cover photo: © CC Or Hitch 3 Introduction Rt Hon Viscount Brentford oncordis International has worked—not always under that name—for over 25 C years to build sustainable and just peace in areas suffering from war, by developing relationships between key individuals on all sides of violent conflict and helping them together to find constructive ways forward. Our field of experience includes South Africa, Rwanda, Sudan, Kenya and Afghanistan. With respect to the Middle East, we have so far limited ourselves to the relatively modest ambitions that available funding has allowed. This paper is the eighth in a series which seeks to build on the strengths of the Concordis approach through spreading understanding of issues and the multilateral consensus developed in consultations, primarily connected with the conflicts in Sudan. -

Palestinian Christians

Palestinian Christians Palestinian Christians are the descendants of the original indigenous Christians who first believed in Jesus Christ. They are the descendants of the disciples of Jesus Christ & the descendants of other Jews, Philistines, Arabs, Aramaeans/Eremites, Canaanites, Greeks, Romans, Persians & Samaritans... who accepted the Messiah when He was with them in the flesh. Today, they live in Nazareth, Bethlehem, Gaza, Nablus, Ramallah, Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa, Jenin, Taybeh, Birzeit, Jifna, al-Bireh, Zababdeh, Tel Aviv, Tubas, Azzun, Aboud, Tiberias, Sakhnin, Shefa-'Amr, Galilee, Jish, Amman, & other places in the Biblical Palestine & Jordan, in addition to the exile. They are Arab Christian Believers of Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, Catholic (eastern & western rites), Protestant, Evangelical & other denominations, who have ethnic or family origins in Palestine. In both the local dialect of Palestinian Arabic and in classical or modern standard Arabic, Christians are called Nasrani (a derivative of the Arabic word for Nazareth, al-Nasira) or Masihi (a derivative of Arabic word Masih, meaning "Messiah"). Christians comprise less than 4% of Palestinian Arabs living within the borders of former Mandate Palestine today (around 4% in the West Bank, a negligible percentage in Gaza, and nearly 10% of Israeli Arabs). According to official British Mandate estimates, Mandate Palestine’s Christian population varied between 9.5% (1922) and 7.9% (1946) of the total population. Demographics and Denominations Today, the majority of Palestinian Christians live abroad. In 2005, it was estimated that the Christian population of the Palestinian territories was between 40,000 and 90,000 people, or 2.1 to 3.4% of the population. -

Kairos Palestine Study Guide

four-week congregational study plan KAIROS PALESTINE a moment of truth faith, hope, and love— a confession of faith and call to action from Palestinian Christians 1 Mennonite Central Committee | Matthew Lester Mennonite Central Committee worker Ed Nyce talked with Abdul J’wad Jabar, whose farm bordered an Israeli settlement in the valley of Bequa’a, Palestine, in 2001. MCC’s partner organizations in Palestine and Israel identified information-sharing as MCC’s most helpful contribution toward peace. CONTENTS SECTION 1 ...............................................................................1 What is the Kairos Palestine document and why should we study it? SECTION 2 ...............................................................................4 The reality on the ground—background facts and maps SECTION 3 ...............................................................................9 A four-week lesson plan outline for congregational study SECTION 4 ............................................................................. 14 Brief history of Mennonite involvement in Palestine-Israel SECTION 5 ............................................................................. 16 The text of the Kairos document © 2016 Israel/Palestine Mission Network of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and Mennonite Palestine Israel Network (MennoPIN) ISBN 978-1-5138-0108-7 2 four-week congregational study plan KAIROS PALESTINE a moment of truth INTRODUCTION Kairos Palestine is the Christian Palestinian’s word to the world about what is happening in Palestine. Its importance stems from the sincere expression of Palestinian Christian concerns for their people and their view of the moment of history they are living through. It is deeply committed to Jesus’ way of love and nonviolence even in the face of entrenched injustice. It seeks to be prophetic in addressing things as they are, without equivocation. It is a contemporary, ecumenical confession of faith and call to action. -

A New Islamophobia

A New Islamophobia By Ilan Halevi Islamophobia, according to Ilan Halevi, is a growing phenomenon in Western countries. Drawing on prejudices against Islam that have deep in roots in Christian European history and thought, the phenomenon has reached unprecedented heights in the post 9/11 political discourse. Its particular power and danger lies in the potential for a broad alliance of otherwise opposed political forces: Muslims and Islam serve as the embodiment of the ultimate enemy for conservatives and the right wingers striving for Western hegemony and racial purity, and for progressives standing up for freedom of expression, rationality, human rights and rights of women. In this way, Islamophobia today serves similar purposes as Anti-Semitism did in the past, and offers a convenient scapegoat and a battle cry to distract and rally those who see their livelihoods and their way of life threatened by the forces of globalization and global capital. Ilan Halevi is a writer and political activist. He has been the representative of Palestine in the Socialist International since 1983, was a member of the Palestinian delegation in the Madrid and Washington negotiations (1991-1993) and Assistant Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs in the Palestinian Government (2003-2005). This work is licensed under the “Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License”. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/de/ Ilan Halevi: A New Islamophobia A phobia is hatred of a given object. Islamophobia: for the new global enemy, Etymologically, it is the desire to flee away from anonymously referred to as “terror”, now has a that object. -

Downloaded License

Exchange 49 (2020) 257-277 brill.com/exch The Revival of Palestinian Christianity Developments in Palestinian Theology Elizabeth S. Marteijn PhD Candidate, School of Divinity, Centre for the Study of World Christianity, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK [email protected] Abstract Palestinian Christians are a minority of approximately 1 or 2% in a context marked by conflict, expulsions, and ongoing emigration. Despite all this, Palestinian Christians have made a significant contribution to society in the spheres of politics, the arts, sci- ence, and social welfare. Moreover, from the 1980s onwards, this Palestinian context of struggle has also been the source for the emergence of a socially and politically committed contextual theology. This article analyses the development of Palestinian contextual theology by examining theological publications by Palestinian theologians. It identifies liberation, reconciliation, witness, ecumenism, and interfaith-dialogue as some of the dominant theological themes. What unites these publications is a theological engagement with the Palestinian Christian identity in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Keywords contextual theology – Israeli-Palestinian conflict – Kairos theology – Palestinian Christianity – Palestinian theology – public theology 1 An Arab Christian Awakening Palestinian Christians feel deeply rooted in Palestinian society. They under- stand themselves as part of the Palestinian community and actively contribute to its flourishing. This article aims to outline how Palestinian Christians have embraced their vocation, in the words of Emeritus Patriarch Michel Sabbah, to © Elizabeth S. Marteijn, 2020 | doi:10.1163/1572543X-12341569 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:35:54PM via free access 258 Marteijn be “in the service of society.”1 Michel Sabbah, born in Nazareth in 1933, was con- secrated on 6th January, 1988, by Pope John Paul II as the first Palestinian-born Roman Catholic Patriarch of Jerusalem. -

Journeying with Real People Towards the Real Bethlehem Could Transform Christmas for You and for Your Friends

Journeying with real people towards the real Bethlehem could transform Christmas for you and for your friends. This is a precious book - precious to keep and precious to give away. Very Rev Dr A. Mclellan, Convener, World Mission Council, Church of Scotland. This book takes the traditional Advent themes of faith, hope and love and looks at them through the lens of ordinary Palestinians, who live in the land we call holy. We hope that it will both inspire you and challenge you as you make the journey towards Christmas. Maggie Lunan, Co-Chair, nativity. The traditional themes of Advent - light out of darkness, hope out of despair, the struggle to give birth to new life in the midst of difficulty and suffering - are here given a reality that is both vigorous and challenging. These reflections from people living on a knife-edge enlarge our vision. Kathy Galloway, Head of Christian Aid Scotland. World Mission Council 121 George Street Edinburgh, EH2 4YR © COS257 10/12 Scottish National Charity Number: SC0 11353 nativity supports Kairos Palestine and is involved dignity. For these reasons we support the rights of all in this resource because we want to encourage people Palestinians and Israelis to live in safety and security, to reappraise Christmas and look at all the celebrations and believe their rights are indivisible from each other. around Christmas with fresh eyes, to challenge the sentimentality of it and offer alternatives that incorporate Christian Aid welcomes the Kairos document as an ‘Just God’. As part of the bigger picture this resource important way of engaging the churches in the UK and offers the opportunity to consider the reality both of Ireland with peace and justice in Israel and the occupied Christmas past and Christmas present in Bethlehem. -

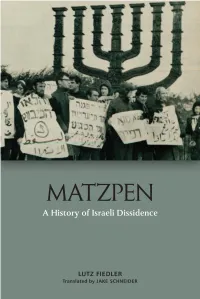

9781474451185 Matzpen Intro

MATZPEN A History of Israeli Dissidence Lutz Fiedler Translated by Jake Schneider 66642_Fiedler.indd642_Fiedler.indd i 331/03/211/03/21 44:35:35 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com Original version © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, 2017 English translation © Jake Schneider, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5116 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5118 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5119 2 (epub) Th e right of Lutz Fiedler to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Originally published in German as Matzpen. Eine andere israelische Geschichte (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017) Th e translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Th yssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Offi ce, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

The View from Here Artists // Public Policy Ceu School of Public Policy Annual Conference June 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 2016 Another Day Lost: 1906 and Counting

the view from here artists // public policy ceu school of public policy annual conference june 4 / 5 / 6 / 7 / 2016 Another Day Lost: 1906 and counting... by Syrian artist Issam Kourbaj 1 From Ai Wei Wei to Banksy, we can see art engaging policy and the political sphere. But in an increasingly connected world where cultural production is ever more easily disseminated, how can this engagement be most effective and meaningful? The CEU School of Public Policy’s 2016 annual conference focuses on a series of questions that are not often asked in the world of government or academia. How do artists engage with issues in public policy? How do artistic representations of issues change how they are perceived? Can artists promote wider public engagement in policymaking? How do artists challenge ideas in their societies and to what end? How does humor intersect with politics, censorship, and violence? Focusing on Hungary, India, Mexico, Sudan, and Syria, we are seeking a truly global perspective on issues including democracy, drugs, migration, violence, and censorship. 2 PROGRAM / ART Visit and participate in exhibitions at CEU from June 1-7. Nador u. 11, Body Imaging by Abby Robinson room 002 Precise office hours will be announced soon. Body Imaging, an installation/performance/photography piece, affords a unique collaborative occasion to make photos of all types of bodies, allowing people to display as much/little exhibitionism as they wish in a protected, safe environment. EXAMINATION: Only doctors & photographers examine people’s bodies at distances reserved for lovers. In my performative role as “photo practitioner,” I peer at people’s selected body parts at incredibly close range. -

Shaping the Peace to Come Trying to Help

Trying to help, shaping the peace to come the scandinavian role in the middle east In spite of the diversity of national situations, there is undoubtedly a Scandinavian dimension in political culture, not only economic and environmental, but also in the field of foreign policy. This is particularly true insofar as the Middle East, and the Palestinian- Israeli conflict in particular, is concerned. Ilan Halevi is the Fatah representative in the Socialist International, a member of the plo, and a writer.1 4o with which those parties took their mem- bership in the Socialist International (si), made the latter a privileged instrument, or at least a positive echo-chamber, of Scandi- navian Middle East policies. Having per- sonally represented the plo and Fatah in the si for more than two decades, I have been a privileged witness to this process, the implications of which are still highly relevant to the present day impasses. Of course, this is a specific angle of vision and recollection, and may not constitute the whole picture: attempts to put an end to the conflict came from many quarters, includ- ing the us, but also the ussr, as well as Ceausescu’s Romania or Tito’s and post- Tito Yugoslavia. Recently, South Africa, for example, has also joined the group of states trying to contribute to the Middle East peace process. The matter here is to high- text: Ilan Halevi light the distinct Scandinavian role: not to claim it was the most decisive one, or the from a “narrow” Palestinian point of sole relevant one. view, “Nordic” involvement with the con- The most decisive factor in whatever flict is marked, as early as 1948, with the progress has been achieved throughout the assassination, by Zionist extremists, of un years in the direction of peace remains the Mediator Folke Bernadotte, because he double capacity of the Palestinian people to refused to endorse the Israeli occupation of resist occupation and national obliteration, Jerusalem and demanded the return of the and to aspire to a peaceful settlement on Palestinian refugees to their homes. -

Archbishop Theodosios Atallah Hanna, Archbishop of Sebastia, Palestine

International Conference on Religious Tourism: Fostering sustainable socio-economic development in host communities Bethlehem, State of Palestine, 15-16 June 2015 Session 4: Inclusive socio-economic development of local communities – promoting partnerships that work Archbishop Theodosios Atallah Hanna, Archbishop of Sebastia, Palestine Bio: Theodosios (Hanna) of Sebastia (born 1965) is the Archbishop of Sebastia from the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem. Ordained on the 24 December 2005 at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, he is the second Palestinian to hold the position of Archbishop in the history of the diocese. Born Atallah Hanna in Rameh to Eastern Orthodox parents in the Upper Galilee, Archbishop Theodosios studied Greek in Jerusalem, continuing his studies in Greece where he earned his Master of Theology from University of Thessalonica School of Theology in 1991. Active in public life, he has served as the spokesperson and Director of the Patriarchate’s Arab Department, has taught in local schools, and lectured on Christianity at the Haifa Arab Teachers’ College. For his devotion to ministry in the Holy Land, Theodosios was granted an honorary Doctor of Theology degree from the Sofia Theological Institute in Bulgaria and the title of Archimandrite. Theodosios gained renown for his high-profile political activism, his outspoken denunciation of the occupation, and his stress upon the importance of Palestinian identity. Theodosios also served as a member of the Constitutional Consultative Committee that worked on the third draft of the Palestinian constitution of March 2003 and was awarded the Jerusalem Prize by the Palestinian National Authority’s Ministry of Culture in 2004. He is also one of the authors of Kairos Palestine together with Patriarch Michel Sabah, Naim Ateeq, Rifat Odeh Kassis, Nora Qort and others.