A Demographic and Dietary History of Ancient Dogs in the Americas Using Ancient Dna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee

From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Miller, Darcy Shane Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 09:33:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/320030 From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee by Darcy Shane Miller __________________________ Copyright © Darcy Shane Miller 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Darcy Shane Miller, titled From Colonization to Domestication: A Historical Ecological Analysis of Paleoindian and Archaic Subsistence and Landscape Use in Central Tennessee and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Vance T. Holliday _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Steven L. Kuhn _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) Mary C. Stiner _______________________________________________________________________ Date: (4/29/14) David G. Anderson Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Aartswoud, 210, 211, 213, 217 Abri Dufaure, 221, 225, 257 Abydos

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-86617-0 - Birds Dale Serjeantson Index More information INDEX Aartswoud, 210, 211, 213, 217 American coot, 106, 108, 122, 147, 403 Abri Dufaure, 221, 225, 257 American Ornithologist’s Union, 419 Abydos, 245 American Southwest, 177, 189, 193, 289, 291, Acheulian culture, 261 292, 312, 333, 345, 399, 400, 450 Africa, 3, 9, 72, 165, 180, 261, 280, 285, 311, 333. amulet, 200, 201, 226, 227, 229, 359. See also See also North Africa, South Africa, talisman West Africa analogue fauna, 369 African collared dove, 304 Anasazi, 289, 292 African goose. See Chinese goose Anatolia, 271, 320, 337, 354, 359. See also age class, 45–47, 240, 267 Turkey ageing, 35–38, 45, 398. See also fusion, ancient DNA, 34, 285, 292, 314, 396, 399 porosity albatross, 69 bone length, 43, 44, 46, 61 chicken, 69, 268, 273 incremental lines, 40–43 grey geese, 69, 296-297 line of arrested growth (LAG), 40, 42 turkey, 291 Aggersund, 200, 257, 449 Andean condor, 9, 403 agricultural clearance, 315, 365, 374, 377, 385 Anglo-Saxon period, 225, 297, 299, 344, agriculture, 252, 265, 300, 306, 376, 381, 383 364 marginal, 230, 263, 400 Animal Bone Metrical Archive Project, 71, Ain Mallaha, 372 421 Ainu, 206, 336 Antarctica, 14, 252, 266 Ajvide, 51, 154, 221, 259 anthropogenic assemblage, 156 Alabama, 211 recognising, 100, 104, 130–131 Alaska, 14, 195, 210, 226, 246, 363 Apalle Cave, 376, 377 Aldrovandi, 274, 303 Apicius, 341, 343 Aleutian Islands, 204, 214, 216, 226, 231, 252, Aquincum, 342, 351 445 Arabia, 316, 325 Alligator site, 198 archaeological project manager, 84, 343, 397 Alpine chough. -

Climatic Variability at Modoc Rock Shelter (Illinois) and Watson Brake (Louisiana): Biometric and Isotopic Evidence from Archaeological Freshwater Mussel Shell

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2009 Climatic variability at Modoc Rock Shelter (Illinois) and Watson Brake (Louisiana): biometric and isotopic evidence from archaeological freshwater mussel shell Sarah Mistak Caughron Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Caughron, Sarah Mistak, "Climatic variability at Modoc Rock Shelter (Illinois) and Watson Brake (Louisiana): biometric and isotopic evidence from archaeological freshwater mussel shell" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 1070. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/1070 This Graduate Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATIC VARIABILITY AT MODOC ROCK SHELTER (ILLINOIS) AND WATSON BRAKE (LOUISIANA): BIOMETRIC AND ISOTOPIC EVIDENCE FROM ARCHAEOLOGICAL FRESHWATER MUSSEL SHELL By Sarah Mistak Caughron A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology in the Department of Anthropology and Middle Eastern Cultures Mississippi State, Mississippi December 2009 Copyright 2009 By Sarah Mistak Caughron CLIMATIC VARIABILITY AT MODOC ROCK SHELTER (ILLINOIS) AND WATSON BRAKE (LOUISIANA): BIOMETRIC -

1990 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

MIDWEST ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE 35th ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS October 5-6, 1990 Northwestern University Evanston, Illinois REF Conferenc MAC 1990 I ~~F ~e,.A.~~ rt.AC. ~ MIDWEST ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE 35th ANNUAL MEETING PROGRAM October 5-6, 1990 Northwestern University Evanston, Illinois ARCHIVES Office of the State Archaeologist The University of Iowa Iowa City, IA 52242 35th MIDWEST ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY October 5-6, 1990 Friday Morning - OCTOBER 5, 1990 [ 1 ] General Session: HISTORIC PERIOD RESEARCH Norris, McCormick Auditorium Chairperson: Rochelle Lurie 1 0 :00 Steven Hackenberger; MACKTOWN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATIONS, WINNEBAGO COUNTY, IWNOIS 10:20 Mark E. Esarey; 1989 EXCAVATIONS AT FT.GRATIOT, PORT HURON, MICHIGAN 10:40 Floyd Mansberger and Joseph Phllllppe; THE EARLY 1870S FARMER'S MARKET: CERAMICAVAIIJ\8I1..lTY' AND ECONOMIC SCALING AT THE FARMERS HOME HOTEL. GALENA, IWNOIS 11 :00 Break 11 :20 Marilyn R. Orr and Myra J. Giesen; STATURE VARIATION AMONG AMERICAN CIVIL WAR SOLDIERS 11 :40 Mark Madsen end Kevin Christensen; A GREAT LAKES FORE-AFT RIGGED SCHOONER FROM THE MID-19TH CENTURY [ 2 J General Session: NEW IDEAS ON OLD PROBLEMS Norris, 2C 1 0 :20 J. Peter Denny; THE ALGONQUIAN MIGRATION FROM THE COLUMBIA PLATEAU TO THE MIDWEST, CIRCA 1800 B.C.: CORRELATING LINGUISTICS AND ARCHAEOLOGY 1 0 :40 James A. Marshall; THE PREHISTORIC PARALLEL STRAIGHT WALLS OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA EXAMINED FOR ASTRONOMICALORIENrATIONS 11 :00 Harry Murphy; BUREAUCRACY, THE AGENCY ARCHAEOLOGIST, AND -

A Late Archaic and Woodland Site in Northeastern Illinois Peter John Geraci University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2016 The rP ehistoric Economics of the Kautz Site: a Late Archaic and Woodland Site in Northeastern Illinois Peter John Geraci University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Geraci, Peter John, "The rP ehistoric Economics of the Kautz Site: a Late Archaic and Woodland Site in Northeastern Illinois" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1141. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1141 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PREHISTORIC ECONOMICS OF THE KAUTZ SITE: A LATE ARCHAIC AND WOODLAND SITE IN NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS by Peter J. Geraci A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Degree of Masters of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2016 ABSTRACT THE PREHISTORIC ECONOMICS OF THE KAUTZ SITE: A LATE ARCHAIC AND WOODLAND SITE IN NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS by Peter J. Geraci The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under The Supervision of Robert J. Jeske, Ph.D. The Kautz Site (11DU1) is a multi-component archaeological site located in the DuPage River Valley in northeastern Illinois. It was inhabited at least six different times between the Late Archaic and Late Woodland periods ca. 6000-1000 B.P. The site was excavated over the course of three field seasons between 1958 and 1961, but the results were never made public. -

2008 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Midwest Archaeological Conference Mound 10 Nitschke Mounds (47DO27) Dodge County, Wisconsin October 15-19, 2008 Milwaukee, WI Midwest Archaeological Conference Annual Meeting Schedule October 15-19, 2008 Hyatt Regency Hotel 333 West Kilbourn Avenue Milwaukee, WI 53203 Wednesday October 15, 2008 7:00-9:00 PM Early Registration and Reception at the Hyatt Regency Cash Bar, with soft drinks available. Thursday October 16, 2008 Thursday Morning Enjoy the city. Milwaukee Public Museum, Art Museum, Discovery World are all nearby. Thursday Afternoon 1:15-4:30 PM Symposium: Human Bone as Cultural Object: A Midwestern Perspective Organizers: Eve Hargrave, Shirley J. Shermer, Kristin M. Hedman (ITARP) and Robin Lillie Room: Lakeshore A 1:15 Shermer, Shirley J. (Office of the State Archaeologist, University of Iowa) Opening Remarks. 1:30 Johnston, Cheryl A. (Western Carolina University) More than Skulls and Mandibles: An Unusual Mortuary Practice from an Early Woodland Context in Central Ohio 1:45 Nawrocki, Stephen P. (University of Indianapolis) and Paul Emanovsky (Joint POW/MIA Command, Central Identification Laboratory) Modified Hopewellian Trophy Jaws 2:00 Cobb, Dawn E. (Illinois State Museum/Illinois Historic Preservation Agency) Interpretations of Modified Human Jaw Bones from Hopewellian Mound Sites in the Central Illinois River Valley 2:15 Lee, Anne B. (Hardlines Design Company) and Cheryl A. Johnston (Western Carolina University) Phallic Batons Made of Bone in the Collections of the Ohio Historical Society 2:30 Carr, Christopher (Arizona State University) and Anna Novotny (Arizona State University) Ritual Dramas in Ohio Hopewell Earthworks 2:45 Schermer, Shirley J. (Office of the State Archaeologist, University of Iowa) and Robin M. -

Late Paleo-Indian Period Lithic Economies, Mobility, and Group Organization in Wisconsin Ethan Adam Epstein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Late Paleo-Indian Period Lithic Economies, Mobility, and Group Organization in Wisconsin Ethan Adam Epstein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Climate Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Epstein, Ethan Adam, "Late Paleo-Indian Period Lithic Economies, Mobility, and Group Organization in Wisconsin" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1361. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1361 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LATE PALEO-INDIAN PERIOD LITHIC ECONOMIES, MOBILITY, AND GROUP ORGANIZATION IN WISCONSIN by Ethan A. Epstein A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology at University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee Fall 2016 ABSTRACT LATE PALEO-INDIAN PERIOD LITHIC ECONOMIES, MOBILITY, AND GROUP ORGANIZATION IN WISCONSIN by Ethan A. Epstein University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Robert J. Jeske The following dissertation focuses upon the organization of Pleistocene / Holocene period lithic technology in Wisconsin circa 10,000 – 10,500 years before present. Lithic debitage and flaked stone tools from the Plainview/Agate Basin components of the Heyrman I site (47DR381), the Dalles site (47IA374), and the Kelly North Tract site at Carcajou Point (47JE02) comprise the data set. These Wisconsin sites are located within a post glacial Great Lakes dune environment, an inland drainage/riverine environment, and an inland wetland/lacustrine environment. -

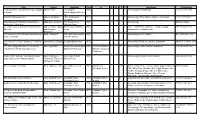

Title Author Publisher Date in V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number

Title Author Publisher Date In V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number Field Manual for Avocational Archaeologists Adams, Nick The Ontario 1994 1 Archaeology, Methodology CC75.5 .A32 1994 in Ontario Archaeological Society Inc. Prehistoric Mesoamerica Adams, Richard E. Little, Brown and 1977 1 Archaeology, Aztec, Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan F1219 .A22 1991 W. Company Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Addington, Lucile R. The University of 1986 Archaeology 000Unavailable Artifacts for Publication Chicago Press The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North Adney, Edwin Tappan Smithsonian Institution 1983 1 Form, Construction, Maritime, Central Canada, E98 .B6 A46 1983 America and Howard I. Press Northwestern Canada, Arctic Chappelle The Knife River Flint Quarries: Excavations Ahler, Stanley A. State Historical Society 1986 1 Archaeology, Lithic, Quarry E78 .N75 A28 1986 at Site 32DU508 of North Dakota The Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Tassili N' Mazonowicz, Douglas Douglas Mazonowicz 1970 1 Archaeology, Rock Art, Sahara, Sandstone N5310.5 .T3 M39 1970 Ajjer The Archeology of Beaver Creek Shelter Alex, Lynn Marie Rocky Mountain Region 1991 Selections form the 3 1 Archaeology, South Dakota, Excavation E78 .S63 A38 1991 (39CU779): A Preliminary Statement National Park Service Division of Cultural Resources People of the Willows: The Prehistory and Ahler, Stanley A., University of North 1991 1 Archaeology, Mandan, North Dakota E99 .H6 A36 1991 Early History of the Hidatsa Indians Thomas D. Thiessen, Dakota Press Michael K. Trimble Archaeological Chemistry -

Late Paleoindian Through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-1998 Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama Renee Beauchamp Walker University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Renee Beauchamp, "Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1998. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1873 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Renee Beauchamp Walker entitled "Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave, Alabama." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Anthropology. Walter E. Klippel, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Paul W. Parmalee, Gerald F. Schroedl, David A. Etnier, Boyce N. Driskell Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Renee Beauchamp Walker entitled "Late Paleoindian through Middle Archaic Faunal Evidence from Dust Cave , Alabama ." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requi rements for the degree of Doctor of Ph ilosophy, with a ma jor in An thropology . -

An Oneota Manifestation in the Central Des Moines River Valley Nancy Mae Osborn Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1976 The lC arkson site (13WA2): an Oneota manifestation in the Central Des Moines River Valley Nancy Mae Osborn Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Osborn, Nancy Mae, "The lC arkson site (13WA2): an Oneota manifestation in the Central Des Moines River Valley" (1976). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16714. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16714 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Clarkson site (13WA2): An Oneota manifestation in the Central Des Moines River Valley by Nancy Mae Osborn A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department: Sociology and Anthropology Major: Sociology (Anthropology) Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1976 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • · . · . 1 General Background • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Statement of Purpose • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2 Methodology • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • · . , . 5 Plan of Presentation • • • • • • • • • • • · . 7 CHAPTER 2. THE ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING • • • • • • • · . 8 The Central Des Moines River Region · . 8 The Clarkson-Carlisle Locale • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 10 CHAPTER 3. THE CULTURE-HISTORICAL SETTING • • • • • • • • • • • 13 Prehistoric and Protohistoric Occupations within the Central Des Moines Valley • • • • • • • • • • • • • • . -

2.15 Paleoindian and Archaic Periods in North America David G

2.15 PALEOINDIAN AND ARCHAIC PERIODS IN NORTH AMERICA DAVID G. ANDERSON Unequivocal evidence for widespread human settlement in and to the south in Latin America. Evidence for earlier human North America dates to c. 13,000 cal BP (all dates herein are in occupation in the Americas prior to c. 13,000 cal BP is reviewed calendar years before present unless explicitly noted), and sites by Michael Collins in this volume (Chapter 2.14), while Archaic are recognised by the presence of bifacial fl uted Clovis - style and subsequent occupations in other parts of the continent up projectile points, named after a town in eastern New Mexico to and after c. 3000 cal BP are summarised by several authors in where they were found in stratigraphic complex in the 1930s later chapters. and after at the nearby site of Blackwater Draw (Boldurian & Clovis points, the diagnostic artifacts used to identify Cotter 1999 ) ( Map 2.15.1 ). The ensuing 10,000 years of human these early occupations, have blades that are typically lanceo- occupation in North America, during the temporal interval late or slightly expanding in shape, and range in size from a from c. 13,000 to 3200 cal BP or c. 11,200–3000 14C yr BP , cor- few to 20 cm or so in length, with most under c. 10 to 12 cm responds to what were traditionally known as the Paleoindian ( Fig. 2.15.2 ). They were prepared using a distinctive manu- and Archaic stages of cultural development across much of facturing procedure employing overshot fl aking to produce a the continent, prior to the appearance of agriculture, monu- bifacial shape from a parent core or fl ake, followed by a thin- mental architecture and pottery in many areas ( e.g. -

Volume 1, Number 1 (1989) Presidents Statement Editors Comment Mississippian Faunal Remains from the Lundy Site (11-Jd-140), Jo Daviess County, Illinois Mona L

Volume 1, Number 1 (1989) Presidents Statement Editors Comment Mississippian Faunal Remains from the Lundy Site (11-Jd-140), Jo Daviess County, Illinois Mona L. Colburn Cahokias Immediate Hinterland: The Mississippian Occupation of Douglas Creek Brad Koldehoff Lighting the Pioneer Homestead: Stoneware Lamps from the Kirkpatrick Kiln Site, La Salle County, Illinois Floyd R. Mansberger, John A. Walthall, and Eva Dodge Mounce Rediscovery of a Lost Woodland Site in the Lower Illinois Valley Kenneth B. Farnsworth Volume 1, Number 2 (1989) Horticultural Technology and Social Interaction at the Edge of the Prairie Peninsula Robert J.Jeske The Pike County, Illinois, Piasa Petroglyph Iloilo M. Jones Reconstructing Prehistoric Settlement Patterns in the Chicago Area David Keene Radiocarbon Dates for the Great Salt Spring Site: Dating Saltpan Variation Jon Muller and Lisa Renken The Effectiveness of Five Artifact Recovery Methods at Upland Plowzone Sites in Northern Illinois Douglas Kullen Volume 2 (1990) Foreword John A. Walthall Introduction: A Historical Perspective on Short-Term Middle Woodland Site Archaeology in West-Central Illinois James R. Yingst Isolated Middle Woodland Occupation in the Sny Bottom Gail E. Wagner The Widman Site (11-Ms-866) A Small Middle Woodland Settlement in the Wood River Valley, Illinois Thomas R. Wolforth, Mary L. Simon, and Richard L. Alvey The Point Shoal Site (11-My-97) A Short-Term Havana Occupation along Upper Shoal Creek, Montgom- ery County, Illinois James R. Yingst Coldfoot: A Middle Woodland Subsistence-Activity Site in the Uplands of West-Central Illinois Susana R. Katz The Evidence for Specialized Middle Woodland Camps in Western Illinois Kenneth B.