The Function of Dialogue in the Process of Evangelisation A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uptown Conversation : the New Jazz Studies / Edited by Robert G

uptown conversation uptown conver columbia university press new york the new jazz studies sation edited by robert g. o’meally, brent hayes edwards, and farah jasmine griffin Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 2004 Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Uptown conversation : the new jazz studies / edited by Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-231-12350-7 — ISBN 0-231-12351-5 1. Jazz—History and criticism. I. O’Meally, Robert G., 1948– II. Edwards, Brent Hayes. III. Griffin, Farah Jasmine. ML3507.U68 2004 781.65′09—dc22 2003067480 Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Acknowledgments ix Introductory Notes 1 Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin part 1 Songs of the Unsung: The Darby Hicks History of Jazz 9 George Lipsitz “All the Things You Could Be by Now”: Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus and the Limits of Avant-Garde Jazz 27 Salim Washington Experimental Music in Black and White: The AACM in New York, 1970–1985 50 George Lewis When Malindy Sings: A Meditation on Black Women’s Vocality 102 Farah Jasmine Griffin Hipsters, Bluebloods, Rebels, and Hooligans: The Cultural Politics of the Newport Jazz Festival, 1954–1960 126 John Gennari Mainstreaming Monk: The Ellington Album 150 Mark Tucker The Man 166 John Szwed part 2 The Real Ambassadors 189 Penny M. -

A Power Stronger Than Itself

A POWER STRONGER THAN ITSELF A POWER STRONGER GEORGE E. LEWIS THAN ITSELF The AACM and American Experimental Music The University of Chicago Press : : Chicago and London GEORGE E. LEWIS is the Edwin H. Case Professor of American Music at Columbia University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2008 by George E. Lewis All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewis, George, 1952– A power stronger than itself : the AACM and American experimental music / George E. Lewis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography (p. ), and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-226-47695-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-226-47695-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians—History. 2. African American jazz musicians—Illinois—Chicago. 3. Avant-garde (Music) —United States— History—20th century. 4. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3508.8.C5L48 2007 781.6506Ј077311—dc22 2007044600 o The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. contents Preface: The AACM and American Experimentalism ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction: An AACM Book: Origins, Antecedents, Objectives, Methods xxiii Chapter Summaries xxxv 1 FOUNDATIONS AND PREHISTORY -

Piano Bass (Upright And/Or Electric)

January 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 1 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin Tolleson; Philadelphia: David Adler, Shaun Brady, Eric Fine; San Francisco: Mars Breslow, Forrest Bryant, Clayton Call, Yoshi Kato; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Tampa Bay: Philip Booth; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Belgium: Jos Knaepen; Canada: Greg Buium, James Hale, Diane Moon; Denmark: Jan Persson; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Detlev Schilke, Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Brian Priestley; Japan: Kiyoshi Koyama; Portugal: Antonio Rubio; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

The Freedom Principle Review – an Astounding Fusion of Jazz and Art by Jason Farago | July 17, 2015

The Freedom Principle review – an astounding fusion of jazz and art By Jason Farago | July 17, 2015 Contemporary art has grown omnivorous. These days, in your local white cube, you are as likely to see a dance or an experimental film as a painting. But music, somehow, remains a challenge for arts institutions: too abstract, too personal, too hard to present in three-dimensional space. The calamitous Björk retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art this spring, where visitors had to wear headphones while looking at pop-star relics, was not the only false step lately. This year’s Venice Biennale features numerous musicians, notably the pianist Jason Moran, and yet music still felt like a temporary diversion rather than a coequal of fine art. If all it were remembered for was its engagement with musical history, then The Freedom Principle – an astounding new exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago – would already stand as a landmark. In telling the story of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, a radical organisation of jazz artists founded in 1965, it does a better job than any show I have ever seen at analysing music and conveying its cultural importance. But The Freedom Principle, curated by Naomi Beckwith and Dieter Roelstraete, does even more than that. It shows how the themes of black cultural nationalism in the 1960s – an art engaged with political struggle, and unafraid to speak in a collective voice – continued a modernist artistic tradition of merging art into daily life. And it pushes into the present day, discovering the legacy of an important but under-appreciated musical tradition in contemporary art worldwide, from American sculptors to Albanian video artists. -

Bozza Utima Improvvisazione DEF

! Paul Steinbeck «Like a cake made from five ingredients»: the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s social and musical practices Many music aficionados first encountered the Art Ensemble of Chicago in the 1980s, when the band was touring the world to promote its ECM albums Nice Guys, Full Force, Urban Bushmen, and The Third Decade.1 And a few Art Ensemble fans, mostly on the South Side of Chicago, still remember the group’s early years in the mid-1960s, when its founding members came together in the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and began to explore the practices that would make their perfor- mances so unique: multi-instrumentalism, group improvisation, and fusions of music with poetry, theater, and other forms of intermedia. But the best way to understand the Art Ensemble may be to examine the band’s activities in be- tween these two eras, after the mid-1960s and before the advent of the 1980s. During the ten-year period from 1969 to 1979, the Art Ensemble settled into its ‘classic’ lineup — adding Joseph Jarman and Famoudou Don Moye to the core of Roscoe Mitchell, Malachi Favors Maghostut, and Lester Bowie, a five-man configuration that would remain unchanged for a quarter-century.2 At the same time, the band members established a set of social practices that governed how they related to one another, individually and collectively, in situations ranging from concerts and recording sessions to the group’s busi- ness meetings. In my book Message to Our Folks, published in Italian as Grande Musica Nera, I argue that the Art Ensemble’s social practices were instrumental in 1. -

A Pilgrimage Through the Old Testament

A PILGRIMAGE THROUGH THE OLD TESTAMENT ** Year 3 of 3 ** (Part 2 of 2) Cold Harbor Road Church Of Christ Mechanicsville, Virginia Old Testament Curriculum TABLE OF CONTENTS Lesson 131: JEREMIAH’S MISSION Jeremiah 1-25 .................................................................................................4 Lesson 132: A YOKE FOR JEREMIAH Jeremiah 26-45 ...............................................................................................9 Lesson 133: PROPHESIES OF DOOM Jeremiah 46-52 ...............................................................................................15 Lesson 134: SIN, SUFFERING, AND SORROW Lamentations 1-5 ...........................................................................................18 Lesson 135: LIFE AND TIMES OF EZEKIEL Ezekiel 1-11 ....................................................................................................23 Lesson 136: THAT THEY MIGHT KNOW I AM THE LORD Ezekiel 12-32 ..................................................................................................29 Lesson 137: RATTLE MY BONES Ezekiel 33-48 ..................................................................................................35 Lesson 138: DANIEL AND FRIEINDS ARE FAITHFUL TO GOD Daniel 1 ..........................................................................................................41 Lesson 139: FOUR IN A FURNACE Daniel 2,3........................................................................................................44 Lesson 140: THE WRITING ON THE -

Joseph Jarman: Black Case Volume I & II: Return from Exile May 18, 2020 by Brian Morton

Joseph Jarman: Black Case Volume I & II: Return From Exile May 18, 2020 By Brian Morton Who was the “real” leader of the Art Ensemble of Chicago? As missing-the- point questions go, it’s a good one. Lester Bowie’s “is there a doctor in the house?” schtick made him the most obviously charismatic member. You might cast Roscoe Mitchell as The Composer, until you scan the albums and find that the credits were a lot more democratic. Don Moye, the latecomer, may have completed the line-up, but he was never an engine-room drummer. Malachi Favors was a spirit-presence, often dark and troubling, but he followed as well as led. What we can say without strain is that Joseph Jarman was the group’s intellectual and poet, possessed of a mind that saw music as a continuum activity that aligned with language and the movements of the physical body, also with our place in the world. When he introduced his writings in 1977, he defined exile as “a state of mind that people get into in order to escape from the reality of themselves in the world of the now”, but insisted that it was a state from which it was always possible to return. Much of his music, and his writing, was concerned with that process of restoration. Jarman had included text (recited by Sherri Scott) in his early Delmark recording As If It Were The Seasons, but probably the only well-known text is Non-Cognitive Aspects Of The City, of which Mitchell’s setting became a key component of the AEC repertoire. -

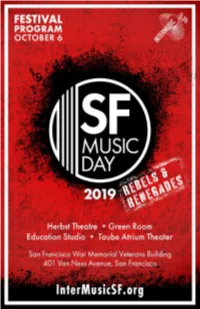

SF-Music-Day-2019-Program-Book-V1.1.Pdf

SF MUSIC DAY 2019 SCHEDULE SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6, NOON–7:45 PM SF WAR MEMORIAL VETERANS BUILDING FIRST SECOND FOURTH FOURTH p. 19 12:00–12:30 p. 36 12:00–12:30 FLOOR FLOOR FLOOR FLOOR JAZZ & Brass Over Bridges CLASSIAL Hristo Vitchev Trio 2nd floor CONTEMPORARY balcony p. 46 12:30–1:00 p. 8 12:45–1:15 12:45–1:15 Quinteto Latino p. 21 CLASSICAL CONTEMPORARY Dee Spencer: JAZZ The Smile Orange Project Fervida Trio CLASSIAL p. 37 1:00–1:30 CONTEMPORARY StringQuake CONTEMPORARY p. 9 1:30–2:00 p. 22 1:30–2:00 p. 47 1:30–2:00 Sylvestris Quartet EARLY CLASSIAL CLASSIAL Stenberg|Cahill Duo CLASSICAL Trance Mission CONTEMPORARY CONTEMPORARY p. 38 2:00–2:45 2:15–2:45 Equity & Opportunity: p. 24 Cornelius Boots A Panel Discussion with Women Music Leaders p. 10 2:30–3:00 & the Heavy Roots p. 49 2:30–3:00 Dresher | Davel Shakuhachi Ensemble CONTEMPORARY in the Bay Area Ensemble for Invented Instrument Duo CONTEMPORARY These Times CONTEMPORARY p. 25 3:00–3:30 Chordless: Sara LeMesh p. 41 3:15–3:45 & Allegra Chapman CLASSIAL CONTEMPORARY Los Tangueros 3:30–4:00 3:30–4:00 p. 12 Del Oeste p. 50 CONTEMPORARY JAZZ Destiny 3:45–4:15 duo B. JAZZ Muhammad Trio p. 26 Experimental Band CONTEMPORARY Keyed Kontraptions CLASSIAL CONTEMPORARY p. 43 4:15–4:45 JAZZ Howard Wiley 4:30–5:00 4:30–5:00 4:30–5:00 p. 13 p. 27 & Extra Nappy p. -

Migration Is the World on the Move

Migration is the world on the move. It is a search for a new meaning; a hope for survival or for better life. With each generation claiming the tangible and the intangible, humanity carries on its own sense of immortality. The migrant leaves everything behind either motivated by domestic menace or seduced by the promises of the new world, in a subconscious search for immortality. Even if this experience might turn into a short-lived illusion, the migrant becomes nevertheless an exemplar of hope and courage, just like Gilgamesh did in his search for immortality. With the immersion into the unknown, the migrant can become anything but a static entity. This is because migration itself is an engine of civilization, claiming a piece of its self-expression and creativity. The perpetual scarcity, or by both, migration has become so unexceptional these days that it will soon claimstate of its creativity own rite ofis motivatedpassage for by the a longgenerations tale of survival. to come. Whether dictated by conflict, by SCIENTIFIC EDITORS Ioan-Gheorghe Rotaru is an educator and a theologian specialized in the philosophy of religion, human rights, church law, and the practice of religious liberty. He is an Associate Professor at ‘Timotheus’ Brethren Theological Institute of Bucharest, and an ordained pastor in the Adventist Church in Romania, North Transylvania Conference, where he worked for 18 years as director of the Public Affairs and Religious Liberty program. He holds two undergraduate degrees (Reformed Theology and Law), one masters degree (Theology), and two doctorates: a PhD in Philosophy (awarded by the Romanian Academy, in Bucharest, Bolyai” University, in Cluj-Napoca, Romania.) Rev. -

Free Jazz CD Listening Notes-Chase

Listening Notes JS 581/IMPRV 481 Jazz Styles: Free Jazz and the Avant Garde Fall 2005 Key: Track number. Title (composer) leader-instrument, musicians-instrument, recording location, recording date (month/day/year), (r=reissue title:) CD or LP title CD 1, Part 1: Precursors of free jazz and the avant-garde 1. Tough Truckin' (Duke Ellington) DE-p, Cootie Williams-t, Rex Stewart-ct, Joe "Tricky Sam" Nanton- tbn, Lawrence Brown-tbn, Juan Tizol-v tbn, Johnny Hodges-ss, Harry Carney-bari, Otto Hardwick-as, Hayes Alvis-b, Billy Taylor-b, Sonny Greer-d Chicago, 3/5/1935 (r) Classics Chronological 1935-1936 An early ostinato-based piece. Also note the attention that Ellington's soloists gave to timbre and envelope (attack, change of timbre and loudness over time, and decay), like many others who began their careers in early jazz of the 1920s. Wide variation of timbre and envelope were less often used as expressive devices (except by a few players) in late swing, bebop and early modern jazz of the late 1930s through the 1950s. Exceptions during that period, especially in rhythm and blues, were viewed by many in the jazz world as unsophisticated, vulgar, and/or a means of pandering to audiences' bad taste. In the 1960s, avant-garde players reclaimed wide variations in timbre and envelope as important expressive parameters. 2. The Clothed Woman (Duke Ellington) DE-p, Harold Baker-t, Johnny Hodges-as, Harry Carney-bari, Junior Raglin-b, Sonny Greer-d NYC, 12/30/1947 (r) Classics Chronological 1947-1948 Ellington's piano playing blends aspects of his stride roots with pedal effects and surprising sonorities -- an example of making the familiar seem strange through exaggeration or isolation of elements. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/55 - Total : 2125 Vinyls Au 25/09/2021 Collection "Jazz" De Cush

Collection "Jazz" de cush Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage A.r. Penck Going Through LP none Allemagne Aacm L'avanguardia Di Chicago LP BSRMJ 001 Italie Abbey Lincoln Painted Lady LP 1003 France Abraham Inc. Tweet Tweet LP LBLC 1711 EU Abus Dangereux Happy French Band LP JB 105 M7 660 France Acid Birds Acid Birds LP QBICO 85 Italie Acting Trio Acting Trio LP 529314 France Adam Rudolph's Moving Pictures... Glare Of The Tiger 2LP Inconnu Ahmad Jamal At The Blackhawk LP 515002 France Aidan Baker With Richard Baker... Smudging LP BW06 Italie Air Open Air Suite LP AN 3002 Etats Unis Amerique Air Live Air LP Inconnu Air Air Mail LP BSR 0049 Italie Air 8o° Below '82 LP 6313 385 France Al Basim Revival LP none Etats Unis Amerique Al Cohn Xanadu In Africa LP Xanadu 180 Etats Unis Amerique Al Cohn & Zoot Sims Either Way LP ZMS-2002 Etats Unis Amerique Alan Silva Skillfullness LP 1091 Etats Unis Amerique Alan Silva Inner Song LP CW005 France Alan Silva Alan Silva & The Celestial Com...3LP Actuel 5293042-43-44France Alan Silva And His Celestrial ... Luna Surface LP 529.312 France Alan Silva, The Celestrial Com... The Shout - Portrait For A Sma...LP Inconnu Alan Skidmore, Tony Oxley, Ali... Soh LP VS 0018 Allemagne Albert Ayler Witches & Devils LP FLP 40101 France Albert Ayler Vibrations LP AL 1000 Etats Unis Amerique Albert Ayler The Village Concerts 2LP AS 9336/2 Etats Unis Amerique Albert Ayler The Last Album LP AS 9208 France Albert Ayler The Last Album LP AS-9208 Etats Unis Amerique Albert Ayler The Hilversum Session LP 6001 Pays-Bas -

Novembre – Decembre 1999

NOVEMBRE – DECEMBRE 1999 LESTER BOWIE NUMBERS 1 & 2 LP NESSA LESTER BOWIE THE 5TH POWER LP BLACK SAINT LESTER BOWIE BRASS I ONLY HAVE EYES FOR YOU / THE ODYSSEY OF CD ECM FUNK & POPUL. MUSIC S ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO PEOPLE IN SORROW LP PATHE ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO A JACKSON IN YOUR HOUSE LP BYG ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO THE THIRD DECADE / FULL FORCE / CD ECM COMING HOME JAMAICA S ART ENSEMBLE OF CHICAGO LIVE IN JAPAN CD DIW 1.MICHEL F. COTE COMPIL ZOUAVE CD AMBIANCES MAGNETIQUES 2.THE RESIDENTS RESIDUE DEUX CD E.S.D. 3.PAPA BOA TÊTE A QUEUE CD AMBIANCES MAGNETIQUES 4.LADDIO BOLOCKO IN REAL TIME CD HUNGARIAN 5.VARIOUS ARTISTS with host PENN JILLETTE RALPH RECORDS 10TH ANNIVERSARY RADIO CD RALPH AMERICA SPECIAL! 6.UNIVERS ZERO THE HARD QUEST CD CUNEIFORM/ORKHESTRA 7.KEUHKOT RUSKEA AIKAKIRJA CD BAD VUGUM 8.VARIOUS ARTISTS STRINGS AND STINGS CD F.B.W.L. 9.LA SOCIETE DES TIMIDES A LA PARADE DES EXPERIENCES DE SURVIE CD PRIKOSNOVENIE OISEAUX 10.LÖBE ONDULATION CD F.B.W.L. 11.UN DEPARTEMENT DES NOUVELLES CD LES COMPAGNONS DE LA TÊTEDEMORT 12.ERIK M FRAME CD METAMKINE 13.BLAST A SOPHISTICATED FACE CD CUNEIFORM/ORKHESTRA 14.PAUL PANHUYSEN PARTITAS FOR LONG STRINGS CD XI 15.NORBERT STEIN PATA MASTERS PATA MAROC CD PATA MUSIC/AMF 16.MIGALA ASI DUELE UN VERANO CD ACUARELA/LABELS 17.YOSHIKAZU IWAMOTO L'ESPRIT DU CREPUSCULE CD BUDA RECORDS 18.N.L.C THE CEREAL KILLER CD EDT/GAZUL/MUSEA 19.MAJU MAJU-1 CD EXTREME 20.CHRIS & COSEY UNION CD CTI 21.ARNO A POIL COMMERCIAL CD DELABEL 22.THE JON SPENCER BLUES EXPLOSION ACME-PLUS CD LABELS 23.PETER FROHMADER/RICHARD