UC Davis Streetnotes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HANLAR BÖLGESİ Osmanlı Devletinin Ilk Önemli Başkenti Olan Bursa’Da Kentin Merkezini Yine Yüzlerce Yıl Çarşı Belirlemiştir

HANLAR BÖLGESİ Osmanlı devletinin ilk önemli başkenti olan Bursa’da kentin merkezini yine yüzlerce yıl çarşı belirlemiştir. İpek Yolu güzergahında bulunan, ilk Osmanlı başkenti Bursa’nın kent kimliğini sergileyen, geleneksel ticaret kimliğini bu günde devam ettiren ve Osmanlı’nın ticaret oluşumunun başlangıcı kabul edilen yapılar bütünü, Tarihi Çarşı ve Hanlar Bölgesi’ dir. BURSA ALAN BAŞKANLIĞI ENVANTER FÖYÜ HANLAR BÖLGESİ (ORHAN GAZİ KÜLLİYESİ VE ÇEVRESİ) “BURSA VE CUMALIKIZIK: OSMANLI İMPARATORLUĞU’NUN DOĞUŞU” UNESCO ADAYLIK BAŞVURU DOSYASI ÇEKİRDEK ALAN(DÜNYA MİRAS ADAYI ALAN) ADI ORHAN GAZİ CAMİSİ PAFTADAKİ NO N 1 İL/İLÇE/MAHALLE BURSA/OSMANGAZİ ENVANTER NO A111 PAFTA/ADA/PARSEL E.18/1040/1 Y.01/5822/1 ADRES NALBANTOĞLU MAH. ORHANGAZİ MEYDANI SOK. YAPTIRAN ORHAN GAZİ MİMAR MİMARİ ÇAĞI OSMANLI DÖNEMİ ANIT YAPIM TARİHİ 1339 KİTABE VAR VAKFİYE N1 İNCELEME TARİHİ 07.05.2012 BAKIMINDAN SORUMLU KURULUŞ VAKIFLAR GENEL MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ BUGÜNKÜ SAHİBİ VAKIFLAR GENEL MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ YAPILAN ONARIMLAR 1417,1619,1629,1732,1773,1782,1794,1808,1863,1905,1963 AYRINTILI TANIM TEKNİK BİLGİLER Su Isınma Elek. Kanaliz. Orhan külliyesinin içindeki caminin kapısı üzerindeki kitabede binanın 1339 yılında Orhan Gazi tarafından x x x x yaptırıldığı, Karamanoğlu Mehmed Bey tarafından 1413 yılında yaktırıldığı, Çelebi Sultan Mehmed döneminde ORJİNAL KULLANIMI 1417 yılında onarıldığı belirtilmektedir. Bursa’daki ilk zaviyeli plan şemalı camidir. Mihrap ekseninde arka arkaya kubbeyle örtülü iki mekan, yanlarda iki tane eyvan ve son cemaat mahalli ile plan tamamlanmıştır. CAMİ Cami’nin ana ibadet mekanının üzerinde sekizgen kasnağa oturan iki kubbe ile yandaki eyvanların üzerinde BUGÜNKÜ KULLANIMI daha küçük kubbeler bulunmaktadır. Duvarları değişik biçimlerde bir araya getirilen moloz taşı ve tuğla ile CAMİ örülen Cami’nin tek minaresi kuzeydoğudadır. -

The Vakf Institution in Ottoman Cyprus

Ottoman Cyprus A Collection of Studies on History and Culture Edited by Michalis N. Michael, Matthias Kappler and Eftihios Gavriel 2009 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 0932-2728 ISBN 978-3-447-05899-5 The Vakf Institution in Ottoman Cyprus Netice Yıldız * Introduction: The legacy of Vakf in Cyprus The pious foundations, called vakf (Turkish: vakıf ) or evkaf (plural) in Cyprus were launched on 15 th September 1570 by converting the cathedral of the city into a mosque and laying it as the first pious foundation in the name of the Sultan followed by others soon after. Since then it has been one of the deep-rooted Ottoman institutions on the island to survive until today under the office of the Turkish Cypriot Vakf Administration (Kıbrıs Türk Vakıflar Đdaresi) (Fig. 1). Alongside its main mission to run all the religious affairs and maintain all religious buildings, it is one of the most important business enterprises in banking, farming and tourism sectors as well as the leading philanthropy organisation in the Turkish Cypriot society. Among its most important charity works is to provide support and service to people of low income status by allocating accommodation at rather low cost, or to give scholarships for young people, as it did in the past, using the income derived from the enterprises under its roof and rents collected from its estates. Besides this, the institution incorporates a mission dedicated to the preservation and restoration of the old vakf monuments in collaboration with the Department of Antiquities and Monuments. Another task of the vakf was to ensure the family properties to last from one generation to the others safely in accordance with the conditions of the deed of foundation determined by the original founder. -

Impact of Land Use Changes on the Authentic Characteristics of Historical Buildings in Bursa Historical City Centre

IMPACT OF LAND USE CHANGES ON THE AUTHENTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF HISTORICAL BUILDINGS IN BURSA HISTORICAL CITY CENTRE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AYŞEGÜL KELEŞ ERİÇOK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING OCTOBER 2012 Approval of the thesis: IMPACT OF LAND USE CHANGES ON THE AUTHENTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF HISTORICAL BUILDINGS IN BURSA HISTORICAL CITY CENTRE submitted by AYŞEGÜL KELEŞ ERİÇOK in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of City and Regional Planning, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Canan ÖZGEN _____________________ Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Melih ERSOY _____________________ Head of Department, City and Regional Planning Prof. Dr. Numan TUNA _____________________ Supervisor, City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Anlı ATAÖV _____________________ City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Numan TUNA _____________________ City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Gül ASATEKİN _____________________ Architecture Dept., Bahçeşehir University Prof. Dr. Ruşen KELEŞ _____________________ Faculty of Political Sciences, Ankara University Prof. Dr. Zuhal ÖZCAN _____________________ Architecture Dept., Çankaya University Date: October 5, 2012 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Ayşegül Keleş Eriçok Signature : iii ABSTRACT IMPACT OF LAND USE CHANGES ON THE AUTHENTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF HISTORICAL BUILDINGS IN BURSA HISTORICAL CITY CENTRE Keleş Eriçok, Ayşegül Ph.D., Department of City and Regional Planning Supervisor: Prof. -

Şehir Ve Ticâret

Şehir ve Ticâret Şehir ve Ticâret ISBN: 978-605-74634-7-0 Esenler Belediyesi Şehir Düşünce Merkezi Şehir Yayınları Yayın No: 23 Editör M. Ebru Erdönmez Dinçer Redaksiyon ve Tashih Cihan Dinar Tasarım - Kapak Mehmet Ülker / Düzey Ajans Baskı / Cilt İlbey Matbaa 2. Matbaacılar Sitesi 3NB3 Topkapı - Zeytinburnu / İSTANBUL 0212 613 83 63 2021 www.aynmedya.com Eserin tüm yayın hakları Esenler Belediyesi’ne aittir. Kitapta yer alan makalelerden yazarları sorumludur. Şehir ve Ticâret Katkıda Bulunanlar M. Ebru ERDÖNMEZ DİNÇER Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Mimarlık Fakültesi’nden 1995 yılında mezun oldu. 1996 yılında YTÜ de araş- tırma görevlisi olarak başladığı akademik kariyerine 2006 yılında Yardımcı Doçent ve 2011 yılında Doçent olarak devam etmektedir. 2006-2007 yılları arasında Almanya Siegen Üniversitesi Mimarlık Bölümü’nde Misafir Öğretim Üyesi olarak ders vermiştir. Çok sa- yıda kitapları, editörlükleri, konferansları, makaleleri bulunan M. Ebru Erdönmez Dinçer aynı zamanda ulu- sal ve uluslararası mimari proje yarışmalarında çeşitli ödüller almıştır. Çalışmalarına hâlen YTÜ Mimarlık Fakültesi Mimarlık Bölümü’nde Doçent olarak devam etmektedir. Hande APAK 2004 İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Mimarlık Fakültesi Mimarlık Bölümü mezunu. 2004-2006 yılları arasında Kayalar İnşaat A.Ş.’de, Harp Akademileri similasyon merkezi ve kütüphane binaları şantiyesinde, 2006- 2009 yılları arasında Som Yapı İnşaat A.Ş’de, 2010- 2012 yılları arasında ASL İnşaat-Kalyon İnşaat’ta ince işler şefi olarak, 2012-2015 yılları asarında Kalyon İnşaat San ve Tic. A.Ş’de mimar olarak çalışmıştır. 2014 yılında Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi, Mimarlık Fa- kültesi Yapı Programı’nda yüksek lisansını tamam- lamıştır. Hâlen, Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Mimarlık Fakültesi’nde Yapı Programı’nda eğitimine devam etmektedir. Kent kimliği, kentsel bellek, kamusal alanlar, yenileyici mimarlık alanlarında çalışmaları devam etmektedir. -

Here Is Another Accounting Due

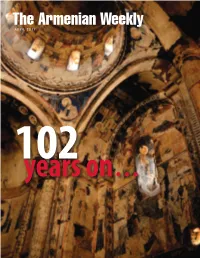

The Armenian Weekly APRIL 2017 102years on . The Armenian Weekly NOTES REPORT 4 Contributors 19 Building Bridges in Western Armenia 5 Editor’s Desk —By Matthew Karanian COMMENTARY ARTS & LITERATURE 7 ‘The Ottoman Lieutenant’: Another Denialist 23 Hudavendigar—By Gaye Ozpinar ‘Water Diviner’— By Vicken Babkenian and Dr. Panayiotis Diamadis RESEARCH REFLECTION 25 Diaspora Focus: Lebanon—By Hagop Toghramadjian 9 ‘Who in this room is familiar with the Armenian OP-ED Genocide?’—By Perry Giuseppe Rizopoulos 33 Before We Talk about Armenian Genocide Reparations, HISTORY There is Another Accounting Due . —By Henry C. Theriault, Ph.D. 14 Honoring Balaban Hoja: A Hero for Armenian Orphans 41 Commemorating an Ongoing Genocide as an Event —By Dr. Meliné Karakashian of the Past . —By Tatul Sonentz-Papazian 43 The Changing Significance of April 24— By Michael G. Mensoian ON THE COVER: Interior of the Church of St. Gregory of Tigran 49 Collective Calls for Justice in the Face of Denial and Honents in Ani (Photo: Rupen Janbazian) Despotism—By Raffi Sarkissian The Armenian Weekly The Armenian Weekly ENGLISH SECTION THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY The opinions expressed in this April 2017 Editor: Rupen Janbazian (ISSN 0004-2374) newspaper, other than in the editorial column, do not Proofreader: Nayiri Arzoumanian is published weekly by the Hairenik Association, Inc., necessarily reflect the views of Art Director: Gina Poirier 80 Bigelow Ave, THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY. Watertown, MA 02472. ARMENIAN SECTION Manager: Armen Khachatourian Sales Manager: Zovig Kojanian USPS identification statement Editor: Zaven Torikian Periodical postage paid in 546-180 TEL: 617-926-3974 Proofreader: Garbis Zerdelian Boston, MA and additional FAX: 617-926-1750 Armenian mailing offices. -

Country City on Product 3Dlm

Country City on product 3dlm - lmic Name alb tirana Resurrection Cathedral alb tirana Clock Tower of Tirana alb tirana The Plaza Tirana alb tirana TEATRI OPERAS DHE BALETIT alb tirana Taivani Taiwan Center alb tirana Toptani Shopping Center alb tirana Muzeu Historik Kombetar and andorra_la_vella Sant Joan de Caselles and andorra_la_vella Rocòdrom - Caldea and andorra_la_vella Sant Martí de la Cortinada and andorra_la_vella Santa Coloma and andorra_la_vella Sant Esteve d'Andorra la Vella and andorra_la_vella La Casa de la Vall and andorra_la_vella La Noblesse du Temps aut bischofshofen Paul Ausserleitner Hill aut graz Graz Hauptbahnhof aut graz Stadthalle Graz aut graz Grazer Opernhaus aut graz Merkur Arena aut graz Kunsthaus Graz aut graz Universität Graz aut graz Technische Universität Graz aut graz Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Graz aut graz Mariatrost aut graz Mausoleum aut graz Vereinigte Bühnen Schauspielhaus Graz aut graz Heiligen Blut aut graz Landhaus aut graz Grazer Uhrturm aut graz Schloss Eggenberg aut graz Magistrat der Stadt Graz mit eigenem Statut aut graz Neue Galerie Graz aut graz Ruine Gösting aut graz Herz Jesu aut graz Murinsel aut graz Dom aut graz Herzogshof aut graz Paulustor aut graz Franciscan Church aut graz Holy Trinity Church aut graz Church of the Assumption am Leech aut graz Mariahilf aut graz Universalmuseum Joanneum, Museum im Palais aut graz Straßengel aut graz Kirche Hl. Kyrill und Method aut graz Kalvarienberg aut graz Pfarrkirche der Pfarre Graz-Kalvarienberg aut graz Glöckl Bräu aut innsbruck -

Cultural Heritage of Turkey

Cultural Heritage of Turkey by Zeynep AHUNBAY © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3230 Handbook Series 9 ISBN: 978-975-17-3448-8 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Photographs Grafiker Printing Co. Archive, Zeynep Ahunbay, Umut Almaç, Mine Esmer, Nimet Hacikura, Sinan Omacan, Robert Ousterhout, Levent Özgün, Nazlı Özgün, Işıl Polat, Mustafa Sayar, Aras Neftçi First Edition Grafiker Printing Co. Print run: 5000. Printed in Ankara in 2009. Second Edition Print and Bind: Kalkan Printing and Bookbinder Ind. Co. www.kalkanmatbaacilik.com.tr - Print run: 5000. Printed in Ankara in 2011. Ahunbay, Zeynep Cultural Heritage of Turkey / Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2011. 184 p.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3230. Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 9) ISBN: 978-975-17-3448-8 I. title. II. Series. 791.53 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 5 I.PREHISTORIC SETTLEMENTS AND ANCIENT SITES 7 Karain 7 Göbeklitepe 8 Çatalhöyük 9 Ephesus 12 Aphrodisias 18 Cultural Heritage of Turkey Heritage of Cultural Lycian Cities 21 Kekova 23 Pergamon 24 Perge 25 Sagalassos 26 Termessos 27 II. MEDIEVAL SITES 29 Myra and St.Nicholas Church 29 Tarsus and St.Paul’s well 30 Alahan Monastery 30 Sümela Monastery 32 III.ANATOLIAN SELJUK ARCHITECTURE 33 Ahlat and its medieval cemetery 33 Diyarbakır City Walls 34 Alanya Castle and Docks 36 St. Peter’s Church 37 Konya, Capital of the Anatolian Seljuks 38 Seljuk Caravansarays 39 IV.OTTOMAN MONUMENTS AND URBAN SITES 42 Bursa 42 Edirne and Selimiye Complex 44 3 Mardin 46 Harran and Urfa 47 Ishak Paşa Palace, Doğubayezıt 47 V. -

Journal of Science Use of Unglazed Brick in Monumental Architecture As

GU J Sci, Part B, 5(2): 1-11(2017) Gazi University Journal of Science PART B: ART, HUMANITIES, DESIGN AND PLANNING http://dergipark.gov.tr/gujsb Use of Unglazed Brick in Monumental Architecture as an Ornamental Element Özlem SAĞIROĞLU1,*, Arzu ÖZEN YAVUZ1 1Gazi University, Faculty of Architecture, Ankara, TÜRKİYE Article Info Abstract Anatolia had been a region for many civilizations that built many religious and cultural Received: 25/08/2016 monumental structures, some of them survived today. One of the most important and common Revised: 20/01/2017 materials used in these structures; which cover crucial information about the properties of these Accepted: 22/05/2017 old civilizations such as their socio-cultural status, religious - administrative decisions, construction technology, traditions and lifestyles; was brick. In many monumental structures; Keywords besides its use in construction, brick was also used within the context of ornamentation; and it became one of the important ornamental elements in certain periods. Within this paper; the use Brick Unglazed brick of brick in Anatolia in ornamental context is studied; weaving systems, dimension, color and Brick Decoration setup are presented in detail covering the Seljukians, principalities and early Ottoman Periods. Brick Ornamentation Terra Cotta 1. INTRODUCTION Since the beginning of history; housing need has constituted one of the essential needs for the survival of mankind. Shelters started to be built later for this need; for which cave and tree hollows had been used formerly; one of the most important construction materials for construction of the shelters was soil as it was possible to be found easily in neighboring area. -

Bursa Ile Ilgili Osmanli Devri Görsel Belgelerinin Sanat

T.C. SAKARYA ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ BURSA İLE İLG İLİ OSMANLI DEVR İ GÖRSEL BELGELER İNİN SANAT TAR İHİ AÇISINDAN DE ĞERLEND İRİLMES İ YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ Nurten ÇALI ŞKAN Enstitü Anabilim Dalı : Sanat Tarihi Tez Danı şmanı: Doç. Dr. Candan NEML İOĞLU EYLÜL – 2010 BEYAN Bu tezin yazılmasında bilimsel ahlak kurallarına uyuldu ğunu, ba şkalarının eserlerinden yararlanılması durumunda bilimsel normlara uygun olarak atıfta bulunuldu ğunu, kullanılan verilerde herhangi bir tahrifat yapılmadı ğını, tezin herhangi bir kısmının bu üniversite veya ba şka bir üniversitenin tez çalı şması olarak sunulmadı ğını beyan ederim. Nurten ÇALI ŞKAN 24.09.2010 ÖNSÖZ Yüzyıllar boyunca ye şiller diyarı olarak anılan Bursa, pek çok sanat eserine konu olmu ştur. Bu sanat eserlerinin bir kısmı müzelerde ve özel koleksiyonlarda yer almaktadır. Bunların dı şında özgün örneklerine ula şılamayan eserler ise albümlerde, seyahatnamelerde ve süreli yayınlarda bulunmaktadır. Bursa’yı tanıtması hedeflenerek bir araya toplanan eserler “Bursa ile ilgili Osmanlı devri görsel belgelerinin sanat tarihi açısından de ğerlendirmesi” konusunu ara ştırmaya de ğer kılmı ştır. Bu çalı şmanın hazırlanmasında yardımlarını esirgemeyen danı şmanım Doç. Dr. Candan Nemlio ğlu’na te şekkürlerimi sunarım. Ayrıca, bu günlere ula şmamda emeklerini hiçbir zaman ödeyemeyece ğim aileme şükranlarımı sunar, çalı şmamı hazırlarken payla şımlarını esirgemeyerek destek olan, İstanbul ve Bursa’daki ö ğretmen arkada şlarıma da te şekkürlerimi ifade etmek isterim. Nurten ÇALI ŞKAN -

Istanbul-Bursa-Trabzon-Tour

PRIVATE FAMILY TOUR FOR NOUFAL PROGRAM Day 1: Welcome to Turkey (20 Dec. 2019) We welcome you at Istanbul Airport. Transfer to the hotel.If you came earlier, we can have a city tour program for today as well. Overnight at 4-5 star hotel in Istanbul Day 2: Discover Old City Istanbul (21 Dec. 2019) Welcome to Istanbul, the heart of the history, culture, and entertainment! The city has a variety of must see places to see but we will just highlight Istanbul in two days. Starting at Topkapi Palace, Hagia Sophia and Sultanahmet Blue Mosque, let's deepen our exploration with in Basilica Cistern, Bayazit Mousque, Beyazıt Square, and Suleymaniye Mosque. Then, Stop at ancient Grand Bazaar for shopping and see its beautiful arts! After that let us move to Çamlica Terrace to see the beautiful night view of Istanbul and have dinner at the top of Istanbul at Çamlıca Hill. See the new biggest mosque with the classical and modern architecture in Çamlıca. Transfer to the hotel and have rest. Overnight at 4-5 star hotel in Istanbul Day 3: Enjoy Istanbul (22 Dec. 2019) Today lets drive to Bosphorus and take a Bosphorus boat tour. See the magnificent architecture of Istanbul from different views. After that let us go to Taksim Square and walk across famous Istiklal Street to Galata Tower. Let’s go to local bazaar and shop there. In the afternoon, let’s cruise to Princess Islands to see beautiful views of islands.. Then, let’s drive to Bursa. Overnight at 3-4 star hotel in Istanbul Day 4: Visit Green Bursa (23 Dec. -

Review of the Development and Change of Tripoli Bazaar in Lebanon

REVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT AND CHANGE OF TRIPOLI BAZAAR IN LEBANON Danah MOHAMAD T.C BURSA ULUDAĞ UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES REVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT AND CHANGE OF TRIPOLI BAZAAR IN LEBANON Danah MOHAMAD 0000-0003-3654-4336 ASSOC. PROF. DR. SELEN DURAK (Supervisor) MSc THESIS DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE BURSA-2020 All Rights Reserved THESIS APPROVAL This thesis, titled "Review of the development and change of Tripoli Bazaar in Lebanon" and prepared by Danah Mohamad has been accepted as an MSc THESIS in Bursa Uludağ University Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Department of Architecture following a unanimous vote of the jury below. Supervisor:Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selen Durak Head: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Selen DURAK Signature 000-0001-7499-8246 Bursa Uludağ University / Architecture Faculty Architecture Member: Prof. Dr. Tulin Vural ARSLAN Signature 000-0003-2072-4981 Bursa Uludağ University / Architecture Faculty Architecture Member: Prof. Dr. Burcu Cingi ÖZÜDURU Signature 0000-0002-8315-2303 Gazi University/ Architecture Faculty City and region planning I approve the above result Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Aksel Eren Institute Director ../../.... I declare that this thesis has been written in accordance with the following thesis writing rules of the B.U.U Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences; All the information and documents in this thesis are based on academic rules, audio, visual and written information and results are in accordance with the scientific code of ethics, in the case that works of others are used, I have provided attribution in accordance with the scientific norms, I have included all attributed sources as references, I have not tampered with the data used, and that I do not present any of this thesis as another thesis work at this university or any other university. -

Turkey Flyer.Indd

DAY 1: SINGAPORE – ISTANBUL DAY 2: ISTANBUL – BURSA (BREAKFAST/LUNCH/DINNER) Tokapi Palace - It was built in between 1466 and 1478 by the Sultan Mehmet Il on top of a hill in a small peninsula, dominating the Golden Isa Bey Mosque - Situated below the basilica of Saint John. The mosque Horn to the north, the Sea of Marmara to the south, and the Bosphorus was built between the years of 1374 and 1375. The mosque was styled strait to the north east, with great views of the Asian side as well. asymmetrically unlike the traditional style, the location of the windows, doors and domes were not matched, purposely. In the entrance of Ulucami - It is a prominent landmark in Bursa’s downtown. With its the mosque, an inscription from the god decorates the doorway. The two towering minarets and 20 domes, the building is one of the most columns inside the house of prayer are from earlier ruins in Ephesus, impressive and important in Bursa. Ulu Cami’i is considered the fi fth most making an interesting contrast to the mosque. important mosque in Islam, after those in Mecca, Medina, Jerusalem, and Damascus. The Grand Mosque was opened in 1399 and built in the Hierapolis & Necropolis - Hierapolis was known for its thermal baths Seljuk style of architecture. and health centre. An ancient Roman spa city founded around 190 B.C., Necropolis means cemetery. In Greek language it means city of dead. DAY 3: BURSA – KUSADASI Necropolis is a large burial site outside the settlement. (BREAKFAST/LUNCH/DINNER) Koza Han - It means the “silk cocoon market”.