By John Munro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European and Chinese Coinage Before the Age of Steam*

《中國文化研究所學報》 Journal of Chinese Studies No. 55 - July 2012 The Great Money Divergence: European and Chinese Coinage before the Age of Steam* Niv Horesh University of Western Sydney 1. Introduction Economic historians have of late been preoccupied with mapping out and dating the “Great Divergence” between north-western Europe and China. However, relatively few studies have examined the path dependencies of either region insofar as the dynamics monetiza- tion, the spread of fiduciary currency or their implications for financial factor prices and domestic-market integration before the discovery of the New World. This article is de- signed to highlight the need for such a comprehensive scholarly undertaking by tracing the varying modes of coin production and circulation across Eurasia before steam-engines came on stream, and by examining what the implications of this currency divergence might be for our understanding of the early modern English and Chinese economies. “California School” historians often challenge the entrenched notion that European technological or economic superiority over China had become evident long before the * Emeritus Professor Mark Elvin in Oxfordshire, Professor Hans Ulrich Vogel at the University of Tübingen, Professor Michael Schiltz and Professor Akinobu Kuroda 黑田明伸 at Tokyo University have all graciously facilitated the research agenda in comparative monetary his- tory, which informs this study. The author also wishes to thank the five anonymous referees. Ms Dipin Ouyang 歐陽迪頻 and Ms Mayumi Shinozaki 篠崎まゆみ of the National Library of Australia, Ms Bick-har Yeung 楊 碧 霞 of the University of Melbourne, and Mr Darrell Dorrington of the Australian National University have all extended invaluable assistance in obtaining the materials which made my foray into this field of enquiry smoother. -

The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864

1 Constructing Ionian Identities: The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864 Maria Paschalidi Department of History University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to University College London 2009 2 I, Maria Paschalidi, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Utilising material such as colonial correspondence, private papers, parliamentary debates and the press, this thesis examines how the Ionian Islands were defined by British politicians and how this influenced various forms of rule in the Islands between 1815 and 1864. It explores the articulation of particular forms of colonial subjectivities for the Ionian people by colonial governors and officials. This is set in the context of political reforms that occurred in Britain and the Empire during the first half of the nineteenth-century, especially in the white settler colonies, such as Canada and Australia. It reveals how British understandings of Ionian peoples led to complex negotiations of otherness, informing the development of varieties of colonial rule. Britain suggested a variety of forms of government for the Ionians ranging from authoritarian (during the governorships of T. Maitland, H. Douglas, H. Ward, J. Young, H. Storks) to representative (under Lord Nugent, and Lord Seaton), to responsible government (under W. Gladstone’s tenure in office). All these attempted solutions (over fifty years) failed to make the Ionian Islands governable for Britain. The Ionian Protectorate was a failed colonial experiment in Europe, highlighting the difficulties of governing white, Christian Europeans within a colonial framework. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

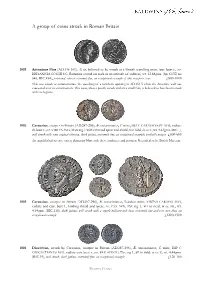

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

Merchants' Magazine: August 1840, Vol. III, No. II

HUNT’S MERCHANTS’ MAGAZINE. A UGUST, 1 840. Art. I.—THE SOUTH SEA BUBBLE. In presenting the remarkable history of this enormous bubble, which in 1720 burst in the British metropolis, overwhelming thousands with the gloom of utter bankruptcy, and crushing their fondest hopes and brightest prospects in the relentless grasp of sudden poverty, we do not claim for it the slightest affinity to the causes that have conspired to produce the com mercial and monetary embarrassments, which have existed in this country for the last few years. Nor do we think it bears the least resemblance to that vast chain of individual credit and personal confidence which, through out the United States, have called into existence a large proportion of our national wealth and internal prosperity. We give it because it mirrors forth the events of an era, more remarkable for the production of imaginary and spectral schemes, by designing and visionary men, than were ever breathed into life and form by the wildest speculations of any other age or period of the world. The universal mania, which then raged, not in England alone, but in France also, conjuring up a thousand dreamy and unsubstantial shapes, which, after assuming the name of some delusive stock, and absorbing the capital and entire fortunes of the credulous multitude, vanished in a single night, and expired with the hopes of its miserable votaries, while the vil- lanous and unprincipled inventors amassed from their fraudulent schemes the wealth of princes, furnishes no lesson which is in the slightest degree -

Medieval Bibliography

American Numismatic Society, Summer Graduate Seminar MEDIEVAL NUMISMATIC REFERENCES Robert Wilson Hoge Literature covering the numismatics of the European Middle Ages is vast and disparate. Numerous useful bibliographical sources exist, but finding relevant citations can be challenging. The attached selections provide merely an introduction and partial overview to materials in several areas, along with some observations. They are by no means exhaustive. Frequently encountered acronyms are listed as they occur in alphabetical sequence in place of the authors’ names. Emphasis has been laid on the more general works rather than the extensive specialized literature in periodical sources. Early Medieval and General (BMC) Wroth, Warwick. 1911. Catalogue of the coins of the Vandals, Ostrogoths and Lombards, and of the empires of Thessalonica, Nicaea and Trebizond in the British Museum. London: the Trustees of the British Museum. Very important, a basic collection, although much new information has been learned during the past 100 years. Chautard, Jules Marie Augustin. 1871. Imitations des monnaies au type esterlin frappés en Europe pendant le XIIIe et le XIVe siècle. Nancy: Impression de l'Académie de Stanislas. This work is “ancient” but has not been superceded. Engel, Arthur, and Raymond Serrure. 1891-1905. Traité de numismatique du moyen âge. 3 vols. Paris: E. Leroux. A general introductory handbook on the subject, standard. Grierson, Philip. 1976. Monnaies du Moyen Age. Fribourg: Office du Livre. Grierson, P. 1991. Coins of Medieval Europe. London. These two works (the latter a shorter, English version of the former) constitute an excellent introduction. Grierson was the international “grand master” of Medieval numismatics. Ilisch, Peter. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2007 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November See below Or by previous appointment. Please note that viewing arrangements on Wednesday 28 November will be by appointment only, owing to restricted facilities. For convenience and comfort we strongly recommend that clients wishing to view multiple or bulky lots should plan to do so before 28 November. Catalogue no. 30 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 172 (front); ex Lot 412 (back); Lot 745 (detail, inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. -

DEBASEMENTS in EUROPE and THEIR CAUSES, 1500-1800 Ceyhun Elgin, Kivanç Karaman and Şevket Pamuk Bogaziçi University, Istanbu

June 2015 DEBASEMENTS IN EUROPE AND THEIR CAUSES, 1500-1800 Ceyhun Elgin, Kivanç Karaman and Şevket Pamuk Bogaziçi University, Istanbul [email protected] Abstract: The large literature on prices and inflation in early modern Europe has not sufficiently distinguished between price increases measured in grams of silver and price increases due to debasements. This has made it more difficult to understand the underlying causes of the variation across Europe in price stability and more generally macroeconomic stability. This paper first provides a continent-wide perspective on the proximate causes of inflation in early modern Europe. We establish that in northwestern Europe debasements were limited and price increases measured in grams of silver were the leading cause of inflation. Elsewhere, especially in eastern Europe, debasements were more freequent and were the leading proximate cause of price increases. The existing literature on debasements based mostly on the experience of western Europe emphasizes both fiscal and monetary causes. We then investigate the fiscal causes of debasements by making use of a new dataset covering 11 countries from western, southern and eastern parts of the continent for the period 1500 to 1800. Our probit regressions suggest that fiscal demands of warfare, low fiscal capacity as measured by tax revenues, and lack of constaints on the executive power were all associated with higher likelihood of debasements for early modern Europe as a whole. Our empirical analysis also points to significant differences between the west and the east of the continent in terms of the causes of debasements. Warfare and low fiscal capacity appear as the leading causes of debasements in eastern Europe (Austria, Poland, Russia and the Ottoman empire). -

British Coins

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH COINS 567 Eadgar (959-975), cut Halfpenny, from small cross Penny of moneyer Heriger, 0.68g (S 1129), slight crack, toned, very fine; Aethelred II (978-1016), Penny, last small cross type, Bath mint, Aegelric, 1.15g (N 777; S 1154), large fragment missing at mint reading, good fine. (2) £200-300 with old collector’s tickets of pre-war vintage 568 Aethelred II (978-1016), Pennies (2), Bath mint, long -

The Medieval English Borough

THE MEDIEVAL ENGLISH BOROUGH STUDIES ON ITS ORIGINS AND CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY BY JAMES TAIT, D.LITT., LITT.D., F.B.A. Honorary Professor of the University MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 0 1936 MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by the University of Manchester at THEUNIVERSITY PRESS 3 16-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13 PREFACE its sub-title indicates, this book makes no claim to be the long overdue history of the English borough in the Middle Ages. Just over a hundred years ago Mr. Serjeant Mere- wether and Mr. Stephens had The History of the Boroughs Municipal Corporations of the United Kingdom, in three volumes, ready to celebrate the sweeping away of the medieval system by the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835. It was hardly to be expected, however, that this feat of bookmaking, good as it was for its time, would prove definitive. It may seem more surprising that the centenary of that great change finds the gap still unfilled. For half a century Merewether and Stephens' work, sharing, as it did, the current exaggera- tion of early "democracy" in England, stood in the way. Such revision as was attempted followed a false trail and it was not until, in the last decade or so of the century, the researches of Gross, Maitland, Mary Bateson and others threw a fiood of new light upon early urban development in this country, that a fair prospect of a more adequate history of the English borough came in sight. Unfortunately, these hopes were indefinitely deferred by the early death of nearly all the leaders in these investigations. -

THE COINAGE of HENRY VII (Cont.)

THE COINAGE OF HENRY VII (cont.) w. J. w. POTTER and E. J. WINSTANLEY CHAPTER VI. Type V, The Profile Coins ALEXANDER DE BRUGSAL'S greatest work was the very fine profile portrait which he produced for the shillings, groats, and halves, and these coins are among the most beautiful of all the English hammered silver. It is true that they were a belated reply to the magnificent portrait coinage which had been appearing on the Continent since as early as 1465 but they have nothing to fear in comparison with the best foreign work. There has always been some doubt as to the date of the appearance of the new coins as there is no document extant ordering the production of the new shilling denomination, nor, as might perhaps be expected, is there one mentioning the new profile design. How- ever, as will be shown in the final chapter, there are good grounds for supposing that they first saw the light at the beginning of 1504. It has been suggested that experimental coins were first released to test public reaction to the new style of portrait, and that this was so with the groats is strongly supported by the marking used for what are probably the earliest of these, namely, no mint-mark and large and small lis. They are all rare and it is clear that regular production was not undertaken until later in 1504, while the full-face groats were probably not finally super- seded until early the following year. First, then, the shillings, which bear only the large and small lis as mark. -

Comparative European Institutions and the Little Divergence, 1385-1800*

n. 614 Nov 2019 ISSN: 0870-8541 Comparative European Institutions and the Little Divergence, 1385-1800* António Henriques 1;2 Nuno Palma 3;4;5 1 FEP-UP, School of Economics and Management, University of Porto 2 CEPESE, Centre for the Study of Population, Economics and Society 3 University of Manchester 4 ICS-UL, Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon 5 CEPR, Centre for Economic Policy Research COMPARATIVE EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS AND THE LITTLE DIVERGENCE, 1385-1800 ? Ant´onioHenriques (Universidade do Porto and CEPESE) Nuno Palma (University of Manchester; Instituto de CiˆenciasSociais, Universidade de Lisboa; CEPR) Abstract Why did the countries which first benefited from access to the New World – Castile and Portugal – decline relative to their followers, especially England and the Nether- lands? The dominant narrative is that worse initial institutions at the time of the opening of Atlantic trade explain Iberian divergence. In this paper, we build a new dataset which allows for a comparison of institutional quality over time. We consider the frequency and nature of parliamentary meetings, the frequency and intensity of extraordinary taxation and coin debasement, and real interest spreads for public debt. We find no evidence that the political institutions of Iberia were worse until at least the English Civil War. Keywords: Atlantic Traders, New Institutional Economics, the Little Divergence JEL Codes: N13, N23, O10, P14, P16 ?We are grateful for comments from On´esimoAlmeida, Steve Broadberry, Dan Bogart, Leonor Costa, Chris Colvin, Leonor Freire Costa, Kara Dimitruk, Rui P. Esteves, Anton´ıFuri´o,Oded Galor, Avner Grief, Phillip Hoffman, Julian Hoppit, Saumitra Jha, Kivan¸cKaraman, Mark Koyama, Nuno Monteiro, Patrick K.