NEWSLETTER the Journal of the London Numismatic Club Joint Honorary Editors of Newsletter DM M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Bibliography

American Numismatic Society, Summer Graduate Seminar MEDIEVAL NUMISMATIC REFERENCES Robert Wilson Hoge Literature covering the numismatics of the European Middle Ages is vast and disparate. Numerous useful bibliographical sources exist, but finding relevant citations can be challenging. The attached selections provide merely an introduction and partial overview to materials in several areas, along with some observations. They are by no means exhaustive. Frequently encountered acronyms are listed as they occur in alphabetical sequence in place of the authors’ names. Emphasis has been laid on the more general works rather than the extensive specialized literature in periodical sources. Early Medieval and General (BMC) Wroth, Warwick. 1911. Catalogue of the coins of the Vandals, Ostrogoths and Lombards, and of the empires of Thessalonica, Nicaea and Trebizond in the British Museum. London: the Trustees of the British Museum. Very important, a basic collection, although much new information has been learned during the past 100 years. Chautard, Jules Marie Augustin. 1871. Imitations des monnaies au type esterlin frappés en Europe pendant le XIIIe et le XIVe siècle. Nancy: Impression de l'Académie de Stanislas. This work is “ancient” but has not been superceded. Engel, Arthur, and Raymond Serrure. 1891-1905. Traité de numismatique du moyen âge. 3 vols. Paris: E. Leroux. A general introductory handbook on the subject, standard. Grierson, Philip. 1976. Monnaies du Moyen Age. Fribourg: Office du Livre. Grierson, P. 1991. Coins of Medieval Europe. London. These two works (the latter a shorter, English version of the former) constitute an excellent introduction. Grierson was the international “grand master” of Medieval numismatics. Ilisch, Peter. -

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes

Ancient, Islamic, British and World Coins Historical Medals and Banknotes To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Thursday 29 November 2007 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 23 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 28 November See below Or by previous appointment. Please note that viewing arrangements on Wednesday 28 November will be by appointment only, owing to restricted facilities. For convenience and comfort we strongly recommend that clients wishing to view multiple or bulky lots should plan to do so before 28 November. Catalogue no. 30 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 172 (front); ex Lot 412 (back); Lot 745 (detail, inside front and back covers) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. -

Ancient Coins

ANCIENT COINS GREEK 6 Argolis, Argos, silver triobol, before 146 BC, forepart of wolf, rev. large ‘A’ within incuse square, wt. 2.01gms. (GCV 2797), toned, very fine £120-150 1 Calabria, Tarentum, circa 272-240 BC, silver didrachm or nomos, magistrate Likinos, wt. 6.46gms. (GCV 363), good very fine £150-200 7 Abataea, miscellaneous Æ issues (22), mostly of Aretas IV (AD 9-40), mainly fine to 2 Lucania, Metapontum, circa340-330 BC, silver very fine (22) £300-400 stater, head of Demeter, rev. barley ear, wt. 7.77gms. (GCV 405), very fine £180-220 ROMAN 8 Rome, Julius Caesar silver denarius, African mint, 47-46 BC. head of Venus right, rev. Aeneas advancing l., carrying palladium in right hand and Anchises on left shoulder, CAESAR downwards to r., fine; other denarii, Republican (5), later (3), including Trajan and Domitian, fair and fine (9) £100-150 3 Lucania, Thourioi, silver stater or didrachm, head of Athena to r., rev. bull to r, wt. 7.45gms. (GCV 446-448), reverse off-centre, toned about very fine £150-200 9 Rome, Nero (54-68 AD), gold aureus, laureate head to r., rev. Jupiter seated l., wt. 5.90gms. (Fr. 94), ex-jewellery, edge shaved, metal flaw behind head, 4 Paphlagonia, Kromna, circa 340-300 BC, silver obverse good fine, reverse fair to fine £300-350 triobol or drachm, head of Zeus, rev. head of Hera, wt. 3.48gms. (GCV 3678), reverse off centre, toned good very fine £200-250 10 Rome, Vespasian (69-79 AD), gold aureus, 69- 70 AD, laureate head to r., rev. -

KING CNUT's LAST COINAGE? Robert L. Schichler on 12

KING CNUT’S LAST COINAGE? Robert L. Schichler On 12 November 1035, Cnut the Great died, leaving uncertain in England the matter of the royal succession, for the king had not named a successor (O’Brien 159). Two of his sons, by different women, were preoccupied in Scandinavia: Swein, Cnut’s eldest son from his earlier union with Ælfgifu of Northampton, had recently been deposed as regent or king of Norway and had fled to seek the support of his half- brother Harthacnut, Cnut’s son by Queen Emma (also called Ælfgifu by the English), who was reigning in Denmark. These two sons, on good terms with each other, then apparently agreed to a geographical division of England, the southern section going to Harthacnut, the northern section to Swein. Because neither of them could leave Denmark at this time, the decision was made that Cnut’s middle son Harold Harefoot, full-brother to Swein and half-brother to Harthacnut, should oversee the affairs of England in their absence (Howard 51-52). This plan, however, met with the objection of Queen Emma, who, distrusting Harold and his mother, was watching out for the interests of her son Harthacnut, and did not wish to lose her own position of power. She had even anticipated such a dreaded development when agreeing to marry Cnut in 1017; mindful of the children of the other Ælfgifu and Cnut, Emma had made it a condition of her acceptance of the marriage that no other son but her own (by Cnut) should succeed to the throne: “But she refused ever to become the bride of Knútr, unless he would affirm to her by oath, that he would never set up the son of any wife other than herself to rule after him, if it happened that God should give her a son by him. -

View a Sample

THE COIN STARTER KIT An Introduction to Coin Collecting and Its History Coin Collecting Lingo Welcome to the world of Obv./Obverse The front of a coin, usually rarity, or whether it is currently legal with the date and main design. tender. Rev./Reverse The back of the coin, Key Date A coin which is difficult to obtain opposite to the obverse. In for the given date, sometimes limited to a Commonwealth coins, this is usually specific grade or coin series. NUMISMATICS depicts the head of the reigning Monarch. Token A privately issued coin, usually with Choice A nice coin at any grade. Not an an exchange value for goods or services official designation, but used to show that at a specific business, rather than being People collect coins for many reasons. It is a a coin is attractive or interesting. issued by a country's Government. challenging and rewarding hobby that can Dull A boring or lacklustre coin, made less Mint A facility which manufactures coins. last a lifetime, and connect you with other impressive by the environment or Set A collection of coins in a series, collectors around the world. Numismatics is cleaning. usually from the same mint. the study or collection of coins and currency. Circulated A coin which shows signs of Mint Set Mints will periodically release wear from being used as currency. groups of coins produced for a particular Collecting coins and other historical items Commemorative A coin issued in year as a set, usually displayed in a coin will teach you about history, the culture and celebration of a person, place, or event. -

Ancient Coins English Hammered and Milled Coins

Ancient Coins 1 Sicily, Syracuse, 485-478 B.C., silver tetradrachm, quadriga r., Nike above, rev. head of Artemis- Arethusa r., within border of four dolphins (S.913/4; Boehringer 112 var.), good very fine, apparently an unpublished combination of dies £700-900 2 Attica, Aegina, 445-431 B.C., silver stater, tortoise, rev. incuse square of skew pattern (S.2600), toned, nearly extremely fine £500-600 3 Ionia, Magnesia, 2nd century B.C., silver tetradrachm, bust of Artemis r., rev. Apollo stg. l., within wreath (cf.S.4485), a few spots of corrosion on obverse, otherwise about extremely fine £350-400 4 Pamphylia, Aspendos, 385-370 B.C., silver stater, two athletes wrestling, rev. slinger advancing r., triskelis in field (S.5390; v. Aulock 4543), well struck, extremely fine or better £320-350 5 Pamphylia, Side, early 2nd century B.C., silver tetradrachm, head of Athena r., wearing Corinthian helmet, rev. Nike advancing l., holding wreath, pomegranate in field (cf.S.5433; v. Aulock 4785), extremely fine £350-400 6 Phoenicia, Tyre, 84/3 B.C., laur head of Melqarth r., rev. eagle l., club and date letters before (S.5921), about very fine £280-300 7 Macedon, Philip II, 359-336 B.C., gold stater, laur. head of Apollo r., rev. biga r., Nike below (cf. S.6663; SNG ANS 159), good very fine or better £1000-1200 8 Macedon, Alexander III, 336-323 B.C., gold stater, Miletos, helmeted head of Athena r., rev. winged Nike stg. l. (S.6702; BMC2114c), good very fine £900-1100 9 Macedon, Alexander III, 336-323 B.C., silver tetradrachm, Mesembria mint, struck 175-125 B.C., head of Heracles r., rev. -

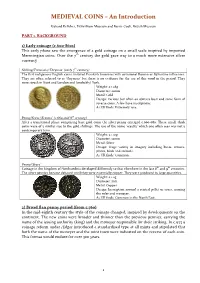

MEDIEVAL COINS – an Introduction

MEDIEVAL COINS – An Introduction Richard Kelleher, Fitzwilliam Museum and Barrie Cook, British Museum PART 1. BACKGROUND 1) Early coinage (c.600-860s) This early phase saw the emergence of a gold coinage on a small scale inspired by imported Merovingian coins. Over the 7 th century the gold gave way to a much more extensive silver currency Shilling/Tremissis/‘Thrymsa’ (early 7 th century) The first indigenous English coins imitated Frankish tremisses with occasional Roman or Byzantine influences. They are often referred to as ‘thrymsas’ but there is no evidence for the use of this word in the period. They were struck in Kent and London and (probably) York. Weight: c.1.28g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Gold Design: various but often an obverse bust and some form of reverse cross. A few have inscriptions. As UK finds: Extremely rare. Penny/Sceat/‘Sceatta’ (c.660-mid 8 th century) After a transitional phase comprising base gold coins the silver penny emerged c.660-680. These small, thick coins were of a similar size to the gold shillings. The use of the name ‘sceatta’ which one often sees was not a contemporary term. Weight: c.1.10g Diameter: 12mm Metal: Silver Design: Huge variety in imagery including busts, crosses, plants, birds and animals. As UK finds: Common. Penny/‘Styca’ Coinage in the kingdom of Northumbria developed differently to that elsewhere in the late 8 th and 9 th centuries. The silver pennies became debased until they were essentially copper. They were produced in large quantities. Weight: c.1.2g Diameter: mm Metal: Copper Design: Inscription around a central pellet or cross, naming the ruler and moneyer. -

Roman and Medieval Coins Found in Scotland, 2006–10 | 227

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 143 (2013), 227–263ROMAN AND MEDIEVAL COINS FOUND IN SCOTLAND, 2006–10 | 227 Roman and medieval coins found in Scotland, 2006–10 J D Bateson* and N M McQ Holmes† ABSTRACT &RLQVDQGRWKHUQXPLVPDWLFÀQGVIURPORFDWLRQVDFURVV6FRWODQGDUHOLVWHGDQGGLVFXVVHG INTRODUCTION alphabetically by location. The type of site is included for the Roman sites of A1, with those This survey lists those coins recovered and on the Antonine Wall preceded by AW, eg ‘AW reported between January 2006 and December fort’. WRJHWKHU ZLWK D IHZ HDUOLHU ÀQGV ZKLFK The medieval catalogue covers all issues have not been included in earlier papers in from the Anglo-Saxon period to the Act of this series. The catalogue and discussion cover Union in 1707. For the 17th century, all gold coins dating from the Roman period to the and silver coins are included, but the numerous Act of Union of 1707 and include all casual Scottish copper coins are not normally listed DQG PHWDOGHWHFWRU ÀQGV ZKLFK KDYH EHHQ individually. Where such coins occur as part of QRWLÀHG WR HLWKHU RI WKH DXWKRUV DV ZHOO DV assemblages containing earlier coins, this fact is KRDUGVIRXQGLQLVRODWLRQDQGDQXPEHURIÀQGV appended to the list. In the discussion section, from archaeological excavations and watching the 17th-century material is again treated EULHIV&RLQÀQGVIURPPDMRUH[FDYDWLRQVZKLFK separately. will be published elsewhere, have, on occasion, In addition to the identity of each coin, not been listed individually, but reference has the following information, where available, is been made to published or forthcoming reports. included in the catalogue: condition/weight/ The format follows that of the previous die axis/location. -

The Control, Organization, Pro Ts and out Put of an Ecclesiastical Mint

Durham E-Theses The Durham mint: the control, organization, prots and out put of an ecclesiastical mint Allen, Martin Robert How to cite: Allen, Martin Robert (1999) The Durham mint: the control, organization, prots and out put of an ecclesiastical mint, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4860/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Durham Mint: the Control, Organization, Profits and Output of an Ecclesiastical Mint Martin Robert Allen Submitted for the Doctorate of Philosophy at the University of Durham, in the Department of Archaeology 1999 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubhshed without his prior written consent, and information derived from it should be acknowledged. This thesis is dedicated to the memory of VERA ADELAIDE ALLEN (nee HANN) (1924-1996) and GEORGE EDWARD ALLEN (1910-1997) Contents List of tables vi List of abbreviations vii Preface x Introduction 1 1. -

By John Munro

THE COINAGES AND MONETARY POLICIES OF HENRY VIII (r 1509–47) Coinage debasements The coinage changes of Henry viii john h. munro the monetary policies of henry viii 424 The infamy of Henry viii’s Great Debasement, which began in 1542 and was continued by his successors for another six years after his death, until 1553, has obscured the previous monetary changes of his reign, especially the two linked debasements of 1526. Certainly the Great Debasement was by far the most severe ever experienced in English monetary history and was one of the worst experienced in early-modern Europe.1 The 1526 debasements and related monetary changes are of interest not only to economic historians but also to readers of the Correspondence of Erasmus, since many of the letters discuss financial transactions that were affected by them. Coinage Debasements Coinage debasement is a complex, arcane, and confusing topic for most read- ers, and indeed for most historians. Put simply, however, we may say that it meant a reduction of the fine precious metals contents, silver or gold, rep- resented in the unit of money-of-account. That generally also meant (though not always) a physical diminution of the precious metal contents in the af- fected coins. Thus the nature and consequences of coinage debasements de- pended on the relationship between coins and moneys-of-account, that is, the accounting system used to reckon prices, values, wages, other payments, receipts of income, and so forth. the relationship between coins and moneys-of-account The English money-of-account, closely based on the monetary system that Charlemagne’s government had established between 794 and 802, was the ***** 1 The four classic accounts of Henry viii’s debasements, are, in chronological order: Frederick C. -

The Hammered Gold Coins of Charles Ii

THE HAMMERED GOLD COINS OF CHARLES II By HERBERT SCHNEIDER SIMON'S portrait of Charles II on the hammered coinage of 1660/62 is almost universally regarded as one of the greatest artistic achievements in English numismatics. It is there- fore surprising that his coins have received so little attention whereas we have an unusually complete literature on Thomas Simon himself and the other engravers who worked at the Tower during the period under review.1 For the matter of that the historical and technical data of the coinage were recorded more than once. Since Ruding2 the evidence was reviewed in a most competent manner by Sir John Craig3 and more recently by Mr. H. G. Stride4 who has gone over the subject again with such a fine comb that there is hardly anything to be added. The evidence contained in the Mint Record Books proved most important and they are clearly a source of information which numismatists have not always sufficiently explored in the past. Indeed, without Mr. Stride's paper certain portions of my research work could only have been conducted against a background of dangerously incomplete facts and figures, and the invaluable collaboration I received from Mr. G. P. Dyer of the Royal Mint for which I am more grateful than I can say, has made it possible to obtain a really coherent general picture. When one considers the importance of the information supplied by Mr. Dyer one begins to appreciate how fatal the destruction of the old Mint Record Books prior to the reign of Charles II really was. -

Coin Auction 19

COIN AUCTION SATURDAY 14 NOVEMBER 2020 Svartensgatan 6, Stockholm MYNTKOMPANIET Svartensgatan 6, 116 20 Stockholm, Sweden Tel. +46 (0)8-640 09 78 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.myntkompaniet.se/auktion Preface Welcome to our Autumn sale! We are glad to present a well filled auction with many interesting items from Sweden and abroad. Despite the pandemic situation our hobby appears to be thriving, with much interest from clients worldwide. We are excited to offer a new website with online live bidding throughout the auction (please see page 4 for more details). This will allow you do bid from home as if you were in the auction room! As always, we will offer floor bidding at our offices throughout the auction, subject to regulations in place by authorities at the time of the auction. As usual we can also offer telephone bidding for important items. This auction offers a small selection of rare high grade classic Swedish items such as an 8 mark 1608 with impressive provenance, a stunning Gustav Vasa daler 1559 and a selection of ducat coinage. There is a wide range of high grade Oscar II and Gustav V coinage from a couple of collections. The foreign section shows a wide selection of taler coinage including multiple talers and high grade items. A Venice 10 zecchini with original mount is a highly unusual offer among a collection of foreign gold coins. We have a selection of foreign banknotes with focus on many unusual Chinese items. We look forward to see you in Stockholm, or participation in the auction through other means.