100Birds of Heronsheadpark.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 3.4 Biological Resources 3.4- Biological Resources

SECTION 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4- BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 3.4 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES This section discusses the existing sensitive biological resources of the San Francisco Bay Estuary (the Estuary) that could be affected by project-related construction and locally increased levels of boating use, identifies potential impacts to those resources, and recommends mitigation strategies to reduce or eliminate those impacts. The Initial Study for this project identified potentially significant impacts on shorebirds and rafting waterbirds, marine mammals (harbor seals), and wetlands habitats and species. The potential for spread of invasive species also was identified as a possible impact. 3.4.1 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES SETTING HABITATS WITHIN AND AROUND SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY The vegetation and wildlife of bayland environments varies among geographic subregions in the bay (Figure 3.4-1), and also with the predominant land uses: urban (commercial, residential, industrial/port), urban/wildland interface, rural, and agricultural. For the purposes of discussion of biological resources, the Estuary is divided into Suisun Bay, San Pablo Bay, Central San Francisco Bay, and South San Francisco Bay (See Figure 3.4-2). The general landscape structure of the Estuary’s vegetation and habitats within the geographic scope of the WT is described below. URBAN SHORELINES Urban shorelines in the San Francisco Estuary are generally formed by artificial fill and structures armored with revetments, seawalls, rip-rap, pilings, and other structures. Waterways and embayments adjacent to urban shores are often dredged. With some important exceptions, tidal wetland vegetation and habitats adjacent to urban shores are often formed on steep slopes, and are relatively recently formed (historic infilled sediment) in narrow strips. -

Late Holocene Anthropogenic Depression of Sturgeon in San Francisco Bay, California

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 35, No. 1 (2015) | pp. 3–27 Late Holocene Anthropogenic Depression of Sturgeon in San Francisco Bay, California JACK M. BROUGHTON Department of Anthropology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 ERIK P. MARTIN Department of Anthropology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 BRIAN MCENEANEY McEaneaney Construction Inc, 10182 Worchester Cir., Truckee, CA 96161 THOMAS WAKE Zooarchaeology Laboratory, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California, Los Angeles DWIGHT D. SIMONS Consulting Archaeologist, 2334 Tiffany Way, Chico, CA Prehistoric resource depression has been widely documented in many late Holocene contexts characterized by expanding human population densities, and has been causally linked to a wide range of other significant changes in human behavior and biology. Some of the more detailed records of this phenomenon have been derived from the San Francisco Bay area of California, including a possible case of anthropogenic sturgeon depression, but evidence for the latter was derived from limited fish-bone samples. We synthesize and analyze a massive ichthyoarchaeological data set here, including over 83,000 identified fish specimens from 30 site components in the central San Francisco Bay, to further test this hypothesis. Allometric live weight relationships from selected elements are established to reconstruct size change in white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) through time, and—collectively—the data show significant linear declines over the last 3,000 years in the relative abundance of sturgeon compared to all other identified fishes, as well as declines in the maximum and mean weights of the harvested fish. Both these patterns are consistent with resource depression and do not appear to be related to changes in the estuarine paleoenvironment. -

Ardea Cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds)

UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour Ardea cinerea (Grey Heron) Family: Ardeidae (Herons and Egrets) Order: Ciconiiformes (Storks, Herons and Ibises) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Grey heron, Ardea cinerea. [http://www.google.tt/imgres?imgurl=http://www.bbc.co.uk/lancashire/content/images/2006/06/15/grey_heron, downloaded 14 November 2012] TRAITS. Grey herons are large birds that can be 90-100cm tall and an adult could weigh in at approximately 1.5 kg. They are identified by their long necks and very powerful dagger like bills (Briffett 1992). They have grey plumage with long black head plumes and their neck is white with black stripes on the front. In adults the forehead sides of the head and the centre of the crown are white. In flight the neck is folded back with the wings bowed and the flight feathers are black. Each gender looks alike except for the fact that females have shorter heads (Seng and Gardner 1997). The juvenile is greyer without black markings on the head and breast. They usually live long with a life span of 15-24 years. ECOLOGY. The grey heron is found in Europe, Asia and Africa, and has been recorded as an accidental visitor in Trinidad. Grey herons occur in many different habitat types including savannas, ponds, rivers, streams, lakes and temporary pools, coastal brackish water, wetlands, marsh and swamps. Their distribution may depend on the availability of shallow water (brackish, saline, fresh, flowing and standing) (Briffett 1992). They prefer areas with tall trees for nesting UWU The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Behaviour (arboreal rooster and nester) but if trees are unavailable, grey herons may roost in dense brush or undergrowth. -

The Grey Heron

Bird Life The Grey Heron t is quite likely that if someone points out a grey heron to you, I you will remember it the next time you see it. The grey heron is a tall bird, usually about 80cm to 1m in height and is common to inland waterways and coasts. Though the grey heron has a loud “fraank” call, it can most often be seen standing silently in shallow water with its long neck outstretched, watching the water for any sign of movement. The grey heron is usually found on its own, although some may feed close together. Their main food is fish, but they will take small mammals, insects, frogs and even young birds. Because of their habit of occasionally taking young birds, herons are not always popular and are often driven away from a feeding area by intensive mobbing. Mobbing is when smaller birds fly aggressively at their predator, in this case the heron, in order to defend their nests or their lives. Like all herons, grey herons breed in a colony called a heronry. They mostly nest in tall trees and bushes, but sometimes they nest on the ground or on ledge of rock by the sea. Nesting starts in February,when the birds perform elaborate displays and make noisy callings. They lay between 3-5 greenish-blue eggs, often stained white by the birds’ droppings. Once hatched, the young © Illustration: Audrey Murphy make continuous squawking noises as they wait to be fed by their parents. And though it doesn’t sound too pleasant, the parent Latin Name: Ardea cinerea swallows the food and brings it up again at the nest, where the Irish Name: Corr réisc young put their bills right inside their parents mouth in order to Colour: Grey back, white head and retrieve it! neck, with a black crest on head. -

Goga Wrfr.Pdf

The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top: Golden Gate Bridge, Don Weeks Middle: Rodeo Lagoon, Joel Wagner Bottom: Crissy Field, Joel Wagner ii CONTENTS Contents, iii List of Figures, iv Executive Summary, 1 Introduction, 7 Water Resources Planning, 9 Location and Demography, 11 Description of Natural Resources, 12 Climate, 12 Physiography, 12 Geology, 13 Soils, 13 -

Bay Fill in San Francisco: a History of Change

SDMS DOCID# 1137835 BAY FILL IN SAN FRANCISCO: A HISTORY OF CHANGE A thesis submitted to the faculty of California State University, San Francisco in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Gerald Robert Dow Department of Geography July 1973 Permission is granted for the material in this thesis to be reproduced in part or whole for the purpose of education and/or research. It may not be edited, altered, or otherwise modified, except with the express permission of the author. - ii - - ii - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Maps . vi INTRODUCTION . .1 CHAPTER I: JURISDICTIONAL BOUNDARIES OF SAN FRANCISCO’S TIDELANDS . .4 Definition of Tidelands . .5 Evolution of Tideland Ownership . .5 Federal Land . .5 State Land . .6 City Land . .6 Sale of State Owned Tidelands . .9 Tideland Grants to Railroads . 12 Settlement of Water Lot Claims . 13 San Francisco Loses Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 14 San Francisco Regains Jurisdiction over Its Waterfront . 15 The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and the Port of San Francisco . 18 CHAPTER II: YERBA BUENA COVE . 22 Introduction . 22 Yerba Buena, the Beginning of San Francisco . 22 Yerba Buena Cove in 1846 . 26 San Francisco’s First Waterfront . 26 Filling of Yerba Buena Cove Begins . 29 The Board of State Harbor Commissioners and the First Seawall . 33 The New Seawall . 37 The Northward Expansion of San Francisco’s Waterfront . 40 North Beach . 41 Fisherman’s Wharf . 43 Aquatic Park . 45 - iii - Pier 45 . 47 Fort Mason . 48 South Beach . 49 The Southward Extension of the Great Seawall . -

50K Course Guide

50K COURSE GUIDE IMPORTANT UPDATES (11/02/2017) • NEW COURSE MODIFICATION - Old Inn to Muir Beach • New 2017 Start & Finish Locations • On-Course Nutrition Information • UPDATED Crew and spectator information RACE DAY CHECKLIST PRE-RACE PREPARATION • Review the shuttle and parking information on the website and make a plan for your transportation to the start area. Allow extra time if you are required or planning to take a shuttle. • Locate crew- and spectator-accessible Aid Stations on the course map and inform your family/friends where they can see you on-course. Review the crew and spectator information section of this guide for crew rules and transportation options. • If your distance allows, make a plan with your pacer to meet you at a designated pacer aid station. Review the pacer information section of this guide for pacer rules and transportation options. • Locate the designated drop bag aid stations and prepare a gear bag for the specific drop bag location(s). Review the drop bag information section of this guide for more information regarding on-course drop bag processes and policies. • Pick up your bib and timing device at a designated packet pickup location. • Attend the Pre-Race Panel Discussion for last-minute questions and advice from TNF Athletes and the Race Director. • Check the weather forecast and plan clothing and extra supplies accordingly for both you and your friends/family attending the race and Finish Festival. It is typically colder at the Start/Finish area than it is in the city. • Make sure to have a hydration and fuel plan in place to ensure you are properly nourished throughout your race. -

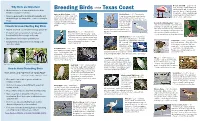

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Flamingos, Stilts and Whales

Nature Vol. 289 29 January 1981 347 Flamingos, stilts and whales from Andrew Milner THE phylogenetic position of the flamingos (family Phoenicopteridae) has long been the subject of controversy among avian systematists with some workers supporting relationship with the Anseriformes (ducks and geese) whilst others favour association with the Ciconiiformes (storks, herons and ibis). The evidence has been reviewed recently by Olson and Feduccia (Relationships and Evolulion oj Flamingos (A ves: Phoenicopteridae) Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 316, Smithsonian Institution Press; 1980) who have developed an earlier proposal by Feduccia that the flamingos fall within the Charadriiformes (waders, gulls and auks). Characteristics of the musculature, the skeleton, the natal down and the endoparasitic cestodes all lead to the conclusion that the closest living relatives of the flamingos are the Recurvirostridae (stilts and avocets) and, more specifically, the Australian Banded Stilt (Cladorhynchus). This remarkable bird lives in colonies frequenting temporary salt lakes in southern Australia and its behaviour, pattern of breeding and life history all bear specific similarities to those of flamingos. The B earliest certain fossil flamingo from the Eocene of Wyoming is described by Head of a Lesser Flamingo, Phoeniconaias minor (A), compared with that of a Black Right Olson and Feduccia and supports their Whale, Eubalaena glacialis (B), to show the hypothesis by being morphologically convergent similarities in the filter·feeding intermediate -

Full Article

NOTORNIS Journal of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand Volume 29 Part 2 June 1982 ISSN 0029-4470 CONTENTS EADES, D. W.; ROGERS, A. E. P. Comments on identification of Magenta Petrel and similar species ...... ...... ...... TUNNICLIFFE, G. A. First sightings of North Atlantic (Cory's) Shearwater in Australasian seas ...... ...... ...... ...... INNES, J. G.; HEATHER, B. D.; DAVIES, L. J. Bird distribution in Tongariro National Park and environs - January 1982 IMBER, M. J.; LOVEGROVE, T. G. Leach's Storm Petrels pros- pecting for nest sites on the Chatham Islands ...... ...... EVANS, R. M. Roosts at foraging sites in Black-billed Gulls ...... SIBLEY, C. G.; WILLIAMS, G. R.; AHLQUIST, J. E. Relation- ships of NZ Wrens as indicated by DNA-DNA hybridization SCHODDE, R.; de NAUROIS, R. Patterns of variation and dispersal in Buff-banded Rail in the South-west pacific and description of a new sub-species ...... ...... ...... ...... SAGAR, P. M.; O'DONNELL, C. F. J. Seasonal movements and population of Southern Crested Grebe in Canterbury ...... O'DONNELL, C. F. J. Food and feeding behaviour of Southern Crested Grebe on Ashburton Lakes ...... ...... ...... Short Notes NORTON, S. A. Bird dispersal of Pseudowintera seed ...... ...... CHILD, P. A new breeding species for Central Otago: Black- fronted Dotterel ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... JENKINS, J. Kermadec Storm Petrel ...... ...... ...... ...... GARRICK, D. P. Young Black-browed Mollymawk inland ...... SIBSON, R. B. Terns perching on wires ...... ...... ...... ...... BELLINGHAM, M.; DAVIS, A. Common Sandpipers in Far North BELLINGHAM, M.; DAVIS, A. A transient colony of Red-billed Gulls ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... HABRAKEN, A. Sooty Terns on Auckland's west coast ...... ...... McLEAN, I. G. Whitehead breeding and parasitism by Long-tailed Cuckoos .. -

Great Egret Ardea Alba

Great Egret Ardea alba Joe Kosack/PGC Photo CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the great egret is listed state endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered/threatened species. All migra- tory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: The Pennsylvania Game Commission counts active great egret (Ardea alba) nests in every known colony in the state every year to track changes in population size. Since 2009, only two nesting locations have been active in Pennsylvania: Kiwanis Lake, York County (fewer than 10 pairs) and the Susquehanna River’s Wade Island, Dauphin County (fewer than 200 pairs). Both sites are Penn- sylvania Audubon Important Bird Areas. Great egrets abandoned other colonies along the lower Susque- hanna River in Lancaster County in 1988 and along the Delaware River in Philadelphia County in 1991. Wade Island has been surveyed annually since 1985. The egret population there has slowly increased since 1985, with a high count of 197 nests in 2009. The 10-year average count from 2005 to 2014 was 159 nests. First listed as a state threatened species in 1990, the great egret was downgraded to endan- gered in 1999. IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS: Great egrets are almost the size of a great blue heron (Ardea herodias), but white rather than gray-blue. From bill to tail tip, adults are about 40 inches long. The wingspan is 55 inches. The plumage is white, bill yellowish, and legs and feet black. Commonly confused species include cattle egret (Bubulus ibis), snowy egret (Egretta thula), and juvenile little blue herons (Egretta caerulea); however these species are smaller and do not nest regularly in the state.