Paris, Hollywood and Kay Kendall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHDWBOAT Began More Tban 20 Years Ago, F RIDAY JAN

Page Twelve TH~ ROCKETEER Friday, January 17, 1964 Taxi Drivers Spruce Up In New Uniforms! Neptune Ball Set For For the first time since NOTS SHDWBOAT began more tban 20 years ago, f RIDAY JAN . Station taxi chauffeurs will be Feb. 7 and 8 at Center " SWORD Of LANeElOT" (115 Min .) Cornel Wilde, Jean Wallace all spruced up in new uniforms, 7 p.m. beginning Monday. (Adventur. in Color) The famed Kni ght is in love w ith King Arthur's intended wife. The uniforms are Navy blue, A suspense, v iolent OCT ion and intrigue with Eisenhower-type jackets. spec io l sel in colorful Comelot. (Adults and The drivers will w e a r white Young People). shirts, black ties and eight-point SATURDAY JAN. 18 " FRANCI S IN TH E NA VY" (80 Min.) caps. Donald O'Connor Mrs. F. III. Mullin, the only 1 p .m. SHORT: " Witty KilTy" (7 M in.) woman chauffe ur, will have a " Ma nhunt No. I S" (1 6 Min.) Navy blue ensemble of skirt and - EVENI NG - jacket, white blouse, black bow· " TH E WRO NG ARM OF THE LAW" (91 Min .) type tie and a WAVE-type hat. Peter Sellers, lionel JeffreYI 7 p .m. Men drivers are J. V. Adam· (Comedy) When on outlide gong muscles son, F. L. Bennett, E. E. Blur· in the owner of on exclulive dresa l a lan (who is also an underworld leader) coop. ton, G. III. Brown, G. H. Davis, erotes w ith Scotland Yord to catch the ch i, B. -

Building Dedication Plans Under Way Another Academy First the Doors at 8949 Wilshire Boule This Year Seems to Be a Year for Vard Are Finally Open

AMPAS PUBlICATIONS Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences library. Beverly Hills. Calif. of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences NUMBER..¥\b FALL, 1975 BEVERLY HILLS, CALIF. Non-Awards TV Special Building Dedication Plans Under Way Another Academy First The doors at 8949 Wilshire Boule This year seems to be a year for vard are finally open. The Academy "firsts" in the history of the Acad has planned a week of Gala Ded emy. The Academy, for the first ication festivities for the official time in its history aside from the opening, December 8, to celebrate Academy Award Presentations, has one of the greatest accomplishments produced a one-hour television in the Academy's 48-year history. special for the ABC network. It is For the first time, the Academy has scheduled to air Nov. 25, from 10-11 all of its facilities housed under one p.m. and will inaugurate a new five roof in a practical and luxurious new year contract with ABC. seven-story building under its own Jack Lemmon, who was awarded ownership. an Oscar for best supporting actor Similar dedication ceremonies for his role in Mr. Roberts twenty are planned for each of five consec years ago, and for best actor for utive evenings. National and inter Save The Tiger in 1974, will host the national press, industry leaders, show, entitled, The Academy Pre civic leaders, governmental leaders, sents Oscar's Greatest Music. The and past Academy Award winners show is a composite of musical will be invited to the black tie Gala numbers from Academy Award Those in the motion p icture industry go to all Dedication ceremonies on the first shows from 1956 through last year, ends to w in an Oscar. -

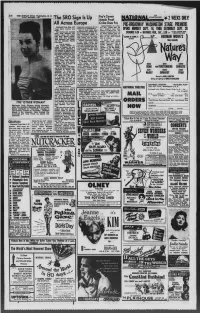

NUTCRACKER Myra Hes*

A-30 THE SUNDAY STAR, Washington, D. C. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 1. JSST Foy's Career CONDITIONED * The SRO Sign Is Up Ample Proof # 2 WEEKS ONLY! All Across Europe Crime Does Pay HOLLYWOOD (/P).—Who- PRE-BROADWAY WASHINGTON STAGE PREMIERE Continued From File A-29 theatrical experiences for the ever said, "Crime does not “Lons Day’s Journey Into tourist are in Scandinavia. pay,” couldn’t have been Night." One of these takes place thinking of Bryan Foy. The OPENS MONDAY SEPT. 16, THRU SATURDAY SEPT. 20 in Copenhagen's famous Tiv- ' ° The festival also Included veteran producer likes to rip • • ballet from Belgrade and oli Gardens, where each eve- his movie themes from the EVENINGS 8:30 MATINEES WED., SAL 2:30 SUBSCRIPTION SINK Moscow, opera and drama ning thousands swarm to day’s real-life headlines—a.s from Italy, Brecht produc- open-air arena to view vaude- often as not, about factual tions from East Germany, ville variety and the only deed of violence. .iM.auMKiE.pl HERMAN WOUK’S 1 current exhibit of pantomime. V West Germany and Japan, A glance at his movie Players Another experience occurs and the Hablmah credits, some with factual CM* from Israel. a few miles outside this \ I Swedish capital, in the 200- origins, shows such titles as Life in London year-old Drottingholm Thea- “Crime School.” “Road The tireless Oliviers re- Gang.” "Alcatraz < Island," to London, only ter. where ancient stage ma- turned the chinery “Murder in the Big House.” theater center affording a somehow still works and elegant musical plays “Roger Touhy, Gangster” full schedule of regular plays and “Canon City,” the latter and musical comedies (38 on are purveyed. -

During the 1930-60'S, Hollywood Directors Were Told to "Put the Light Where the Money Is" and This Often Meant Spectacular Costumes

During the 1930-60's, Hollywood directors were told to "put the light where the money is" and this often meant spectacular costumes. Stuidos hired the biggest designers and fashion icons to bring to life the glitz and the glamour that moviegoers expected. Edith Head, Adrian, Walter Plunkett, Irene and Helen Rose were just a few that became household names because of their designs. In many cases, their creations were just as important as the plot of the movie itself. Few costumes from the "Golden Era" of Hollywood remain except for a small number tha have been meticulously preserved by a handful of collectors. Greg Schreiner is one of the most well-known. His wonderful Hollywood fiolm costume collection houses over 175 such masterpieces. Greg shares his collection in the show Hollywoood Revisited. Filled with music, memories and fun, the revue allows the audience to genuinely feel as if they were revisiting the days that made Hollywood a dream factory. The wardrobes of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Julie Andrews, Robert Taylor, Bette Davis, Ann-Margret, Susan Hayward, Bob Hope and Judy Garland are just a few from the vast collection that dazzle the audience. Hollywood Revisited is much more than a visual treat. Acclaimed vocalists sing movie-related music while modeling the costumes. Schreiner, a professional musician, provides all the musical sccompaniment and anecdotes about the designer, the movie and scene for each costume. The show has won critical praise from movie buffs, film historians, and city-wide newspapers. Presentation at the legendary Pickfair, The State Theatre for The Los Angeles Conservancy and The Santa Barbara Biltmore Hotel met with huge success. -

HH Available Entries.Pages

Greetings! If Hollywood Heroines: The Most Influential Women in Film History sounds like a project you would like be involved with, whether on a small or large-scale level, I would love to have you on-board! Please look at the list of names below and send your top 3 choices in descending order to [email protected]. If you’re interested in writing more than one entry, please send me your top 5 choices. You’ll notice there are several women who will have a “D," “P," “W,” and/or “A" following their name which signals that they rightfully belong to more than one category. Due to the organization of the book, names have been placed in categories for which they have been most formally recognized, however, all their roles should be addressed in their individual entry. Each entry is brief, 1000 words (approximately 4 double-spaced pages) unless otherwise noted with an asterisk. Contributors receive full credit for any entry they write. Deadlines will be assigned throughout November and early December 2017. Please let me know if you have any questions and I’m excited to begin working with you! Sincerely, Laura Bauer Laura L. S. Bauer l 310.600.3610 Film Studies Editor, Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal Ph.D. Program l English Department l Claremont Graduate University Cross-reference Key ENTRIES STILL AVAILABLE Screenwriter - W Director - D as of 9/8/17 Producer - P Actor - A DIRECTORS Lois Weber (P, W, A) *1500 Major early Hollywood female director-screenwriter Penny Marshall (P, A) Big, A League of Their Own, Renaissance Man Martha -

DRAWING COSTUMES, PORTRAYING CHARACTERS Costume Sketches and Costume Concept Art in the Filmmaking Process

Laura Malinen 2017 DRAWING COSTUMES, PORTRAYING CHARACTERS Costume sketches and costume concept art in the filmmaking process MA thesis Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture Department of Film, Television and Scenography Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television Major in Costume Design 30 credits Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Sofia Pantouvaki and Satu Kyösola for the invaluable help I got for this thesis. I would also like to thank Nick Keller, Anna Vilppunen and Merja Väisänen, for sharing their professional expertise with me. Author Laura Malinen Title of thesis Drawing Costumes, Portraying Characters – Costume sketches and costume concept art in the filmmaking process Department Department of Film, Television and Scenography Degree programme Master’s Degree Programme in Design for Theatre, Film and Television. Major in Costume Design Year 2017 Number of pages 85 Language English Abstract This thesis investigates the various types of drawing used in the process of costume design for film, focusing on costume sketches and costume concept art. The research question for this thesis is ‘how and why are costume sketches and costume concept art used when designing costumes for film?’ The terms ‘costume concept art’ and ‘costume sketch’ have largely been used interchangeably. My hypothesis is that even though costume sketch and costume concept art have similarities in the ways of usage and meaning, they are, in fact, two separate, albeit interlinked and complementary terms as well as two separate types of professional expertise. The focus of this thesis is on large-scale film productions, since they provide the most valuable information regarding costume sketches and costume concept art. -

Profiles in History December 2012 Auction 53 Prices Realized Lot Title Winning Bid Amount 2 Vintage Futuristic City Photograph F

Profiles in History December 2012 Auction 53 Prices Realized Lot Title Winning Bid Amount 2 Vintage futuristic city photograph from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. $1,200 3 Mary Philbin “Christine Daae” photograph from The Phantom of the Opera. $300 4 Louise Brooks publicity portrait. $2,500 5 Louise Brooks portrait for Now We’re in the Air. $400 9 Alfred Cheney Johnston nude portrait of Peggy Page. $1,000 10 Alfred Cheney Johnston oversize nude portrait of Julie Newmar. $1,200 11 Alfred Cheney Johnston Portrait of unidentified seated nude. $600 13 Vintage Carroll Borland as “Luna” photograph from Mark of the Vampire $325 16 Katharine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $200 17 Katharine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $1,100 18 Pair of Katharine Hepburn oversize gallery portraits by Ernest A. Bachrach. $1,700 19 Katharine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $1,200 20 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $475 21 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $650 22 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait for Sylvia Scarlett by Ernest A. Bachrach. $300 23 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $1,200 24 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $450 25 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $450 26 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $225 27 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $200 28 Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portrait by Ernest A. Bachrach. $200 29 Pair of Katherine Hepburn oversize gallery portraits by Ernest A. -

Mitzi Gaynor

Omnibus <^£ectuze Series Presents Mitzi Gaynor Tuesday, Oct. 10, 2000 7:30 p.m. IPFW Walb Student Union Ballroom c£Pvofvam Welcome Michael A. Wartell IPFW Chancellor Introduction Larry L. Life Chair, IPFW Department of Theatre Lecture: 'An Evening with Mitzi Gaynor" Mitzi Gaynor Media sponsors: WBNI 89.1 and NewsChannel 15. The Omnibus Lecture Series is funded by a grant from the English, Bonier, Mitchell Foundation. This Omnibus lecture is cosponsored by the IPFW Department of Theatre, Russell Sunday, and Walter McComb. Thanks to InterVarsity for ushering tonight. Mitzi Gaynor itzi Gaynor, star of stage and screen, is best knownsfor her role as Ensign Nellie llilbpfepin the Rodgeb'and Hamrrierstein musical South Pacific. To describe Mitzi Gaynor is to form a picture of the complete entertainer, which she has been since starting her career at the age of 12 in the corps de ballet of the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera. Her vibrant personality and singing, dancing, and acting talents have since found her as a star of motion pictures, television, the theatrical stage, Las Vegas, and concerts. She was recognized by her peers when the theatrical union of entertainers voted her "Singing and Dancing Star of the Year," presented on national video by George Burns. Gaynor was virtually born into the theatre; her mother was a dancer, her father a professional musician. When the family moved from her native Chicago, she was discovered by legendary Los Angeles theatrical producer Edwin Lester, and made her debut as a dancer in Song without Words for the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense. -

CUL Keller Archive Catalogue

HANS KELLER ARCHIVE: working copy A1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49 A1/1: Unpublished manuscripts, 1940-49: independent work This section contains all Keller’s unpublished manuscripts dating from the 1940s, apart from those connected with his collaboration with Margaret Phillips (see A1/2 below). With the exception of one pocket diary from 1938, the Archive contains no material prior to his arrival in Britain at the end of that year. After his release from internment in 1941, Keller divided himself between musical and psychoanalytical studies. As a violinist, he gained the LRAM teacher’s diploma in April 1943, and was relatively active as an orchestral and chamber-music player. As a writer, however, his principal concern in the first half of the decade was not music, but psychoanalysis. Although the majority of the musical writings listed below are undated, those which are probably from this earlier period are all concerned with the psychology of music. Similarly, the short stories, poems and aphorisms show their author’s interest in psychology. Keller’s notes and reading-lists from this period indicate an exhaustive study of Freudian literature and, from his correspondence with Margaret Phillips, it appears that he did have thoughts of becoming a professional analyst. At he beginning of 1946, however, there was a decisive change in the focus of his work, when music began to replace psychology as his principal subject. It is possible that his first (accidental) hearing of Britten’s Peter Grimes played an important part in this change, and Britten’s music is the subject of several early articles. -

Sydney Program Guide

Page 1 of 28 Sydney Program Guide Sun Apr 5, 2015 06:00 TV SHOP - HOME SHOPPING WS G Home shopping programme. 06:30 TASTY CONVERSATIONS Captioned Repeat HD WS G Apple Cake & Walnut Praline Audra deems this her “healthy indulgence”, a beautiful apple cake with a walnut praline to die for. 06:40 TWICE ROUND THE DAFFODILS 1962 Captioned Repeat WS PG Twice Round The Daffodils A patient's final trial of strength before being discharged is the long, lonely walk twice around the daffodils, as love helps the recovery process and comedy runs riot in the hospital corridors. Starring: Donald Sinden, Juliet Mills, Kenneth Williams, Donald Houston, Ronald Lewis Cons.Advice: Adult Themes 08:30 DANOZ WS G Home shopping programme. 10:00 WENT THE DAY WELL 1942 Captioned Repeat PG Went The Day Well The residents of a British village during WWII welcome a platoon of soldiers who are to be billeted with them. The trusting residents then discover that the soldiers are Germans who proceed to hold the village captive. Starring: Oliver Wilsford, Valerie Taylor Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 12:00 SUBURU NATIONAL ROAD SERIES WS NA Woodside Tour de Perth Highlights of the Woodside Tour de Perth in it's third year, and marks the beginning of the men's Subaru National Road Series. 12:30 THE GARDEN GURUS Captioned Repeat HD WS G Do you know where the best place in the garden is to grow vegetables? Have you ever wondered what fruit leather is and how to make it? Or are you looking for a great place for your child’s next birthday party? The Garden Gurus tackles all these questions and more. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter.