Hodgkin Lymphoma Paolo G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin Lymphoma • Lymphoid neoplasm derived from germinal center B cells. • Neoplastic cells (i.e. Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg/LP cells) comprise the minority of the infiltrate. • Non-neoplastic background inflammatory cells comprise the majority of infiltrate. • Two biologically distinct types: 1. Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma (CHL) 2. Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma (NLPHL) Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma • Neoplastic B (Hodgkin) cells are often take the form of Reed-Sternberg cells or variants – Classic RS, mummified and lacunar cells. • The majority of background, non-neoplastic small lymphocytes are T cells. • Unique immunophenotype that differs from most B cell lymphomas. • Divided into 4 histologic subtypes according to the background milieu: – Nodular Sclerosis – Mixed Cellularity – Lymphocyte Rich – Lymphocyte Deplete CHL - RS Cell Variants Classic RS Cell Lacunar Cells Mummified Cell Hsi ED and Golblum JR. Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology: Hematopathology. 2nd Ed. 2012 CHL - Immunophenotype CD45 CD3 CD20 Pax-5 CD30 CD15 CHL - Histologic Subtypes Nodular Sclerosis • Architecture is effaced by prominent nodules separated by dense bands of collagen. • Mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of T cells, granulocytes, and histiocytes. • Lacunar variants are the predominant form of RS cells. Mixed Cellularity • Architecture is effaced by a more diffuse infiltrate without bands of fibrosis. • Background of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes and eosinophils. • Approximately 75% of cases are positive for EBV-encoded RNA or protein (LMP1) Lymphocyte Rich • Architecture is effaced by a nodular to vaguely nodular infiltrate of lymphocytes. • Nodules may contain regressed germinal centers. • The majority of background, non- neoplastic lymphocytes are B cells; T cells form rosettes around neoplastic cells. • Granulocytes and histiocytes are rare. Regressed germinal center Lymphocyte Deplete • Architecture is effaced by disordered fibrosis and necrosis. -

Mimics of Lymphoma

Mimics of Lymphoma L. Jeffrey Medeiros MD Anderson Cancer Center Mimics of Lymphoma Outline Progressive transformation of GCs Infectious mononucleosis Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease Castleman disease Metastatic seminoma Metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma Thymoma Myeloid sarcoma Progressive Transformation of Germinal Centers (GC) Clinical Features Occurs in 3-5% of lymph nodes Any age: 15-30 years old most common Usually localized Cervical LNs # 1 Uncommonly patients can present with generalized lymphadenopathy involved by PTGC Fever and other signs suggest viral etiology Progressive Transformation of GCs Different Stages Early Mid-stage Progressive Transformation of GCs Later Stage Progressive Transformation of GCs IHC Findings CD20 CD21 CD10 BCL2 Progressive Transformation of GCs Histologic Features Often involves small area of LN Large nodules (3-5 times normal) Early stage: Irregular shape Blurring between GC and MZ Later stages: GCs break apart Usually associated with follicular hyperplasia Architecture is not replaced Differential Diagnosis of PTGC NLPHL Nodules replace architecture LP (L&H) cells are present Lymphocyte- Nodules replace architecture rich classical Small residual germinal centers HL, nodular RS+H cells (CD15+ CD30+ LCA-) variant Follicular Numerous follicles lymphoma Back-to-back Into perinodal adipose tissue Uniform population of neoplastic cells PTGC –differential dx Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant HL CD20 NLPHL CD3 Lymphocyte-rich Classical HL Nodular variant CD20 CD15 LRCHL Progressive Transformation of GCs BCL2+ is -

Hodgkin's Disease Variant of Richter's Syndrome in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Patients Previously Treated with Fludarabin

research paper Hodgkin’s disease variant of Richter’s syndrome in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients previously treated with fludarabine Dominic Fong,1 Alexandra Kaiser,2 Summary Gilbert Spizzo,1 Guenther Gastl,1 Alexandar Tzankov2 The transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) into large-cell 1Division of Haematology and Oncology and lymphoma (Richter’s syndrome, RS) is a well-documented phenomenon. 2Department of Pathology, Innsbruck Medical Only rarely does CLL transform into Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL). To further University, Innsbruck, Austria analyse the clinico-pathological and genetic findings in the HL variant of RS, we performed a single-institution study in four patients, who developed HL within a mean of 107 months after diagnosis of CLL. All were treated with fludarabine. Three cases were Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated mixed cellularity (MC) HL, the fourth was nodular sclerosis (NS) HL without EBV association. The sites involved by HL included supra- and infradiaphragmal lymph nodes and the tonsils; stage IV disease was also documented. All patients presented with CLL treatment-resistant lymphadenopathies and B- symptoms. In two of the MC cases, molecular analysis performed on CLL samples and microdissected Hodgkin and Reed–Sternberg cells (HRSC) suggested a clonal relationship, while in NS no indication of a clonal relationship was detected. In summary, HL can occur in CLL patients at any Received 15 December 2004; accepted for site, up to 17 years after initial diagnosis, especially after treatment with publication 1 February 2005 fludarabine. The majority present with B-symptoms and CLL treatment- Correspondence: A. Tzankov MD, Department resistant lymphadenopathy, are of the MC type, clonally related to CLL and of Pathology, Innsbruck Medical University, might be triggered by an EBV infection. -

CD20-Positive Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: Report of a Case After Nodular Sclerosis Hodgkin’S Disease and Review of the Literature Renee L

CD20-Positive Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: Report of a Case after Nodular Sclerosis Hodgkin’s Disease and Review of the Literature Renee L. Mohrmann, M.D., Daniel A. Arber, M.D. Division of Pathology, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, California CASE REPORT We present a case of peripheral T-cell lymphoma co-expressing CD3 and CD20, as well as demon- A 47-year-old man presented in 1993 with a brief strating T-cell receptor gene rearrangement, in a history of right axillary lymph node enlargement patient who had been diagnosed with nodular scle- and mild fatigue. Biopsy showed nodular sclerosis rosis Hodgkin’s disease 5 years previously. Although Hodgkin’s disease. He was treated with six courses 15 cases of CD20-positive T-cell neoplasms have of mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, been previously reported in the literature, this is the prednisone/doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine first report of CD20-positive T-cell lymphoma oc- chemotherapy over a period of 6 months. Clinical curring subsequent to treatment of Hodgkin’s dis- remission was achieved for 5 years. In early 1998, the patient noticed enlargement of lymph nodes in ease. The current case affords an opportunity to the posterior cervical region, which were followed review the rarely reported expression of CD20 in clinically for several months. Weight loss of 15 lbs., T-cell neoplasms as well as the relationship between fatigue, and flu-like symptoms ensued. The lymph Hodgkin’s disease and subsequently occurring non- nodes became firmer to palpation and were biop- Hodgkin’s lymphomas. In addition, the identifica- sied, showing peripheral T-cell lymphoma, diffuse tion of this case supports the suggestion that the use large-cell type. -

CD20 Over-Expression in Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg Cells of Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma: the Neglected Quest Daniel Benharroch1, Karen Nalbandyan1, Irina Lazarev2

Journal of Cancer 2015, Vol. 6 1155 Ivyspring International Publisher Journal of Cancer 2015; 6(11): 1155-1159. doi: 10.7150/jca.13107 Research Paper CD20 Over-Expression in Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg Cells of Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma: the Neglected Quest Daniel Benharroch1, Karen Nalbandyan1, Irina Lazarev2 1. Department of Pathology, Soroka University Medical Center, Beer-Sheva and Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel 2. Department of Oncology, Soroka University Medical Center, Beer-Sheva and Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel Corresponding author: Prof. Daniel Benharroch, Dept. of Pathology, Soroka University Medical Center, P.O.Box 151, Beer-Sheva, 84101, Israel. Tel: 97286400920. Fax:86232770. e-mail: [email protected] © 2015 Ivyspring International Publisher. Reproduction is permitted for personal, noncommercial use, provided that the article is in whole, unmodified, and properly cited. See http://ivyspring.com/terms for terms and conditions. Received: 2015.07.01; Accepted: 2015.08.08; Published: 2015.09.15 Abstract We have scrutinized a previously analyzed cohort of classical Hodgkin lymphoma patients for evidence of a CD20 over-expression. This was pursued in order to determine whether all the 24 (12.6%) CD20+++ patients had clinical and/or biological profiles which would warrant a separate consideration and treatment or would carry a different outcome from our 166 CD20 (-) classical Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Except for an older age and a significantly lower expression of non-sialyl-CD15 antigen, both previously described in classical Hodgkin lymphoma, no justification to exclude these CD20+++ patients from the cohort at large is apparent. -

Hodgkin Reed–Sternberg-Like Cells in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

diagnostics Review Hodgkin Reed–Sternberg-Like Cells in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma 1 2 3, 4,5, Paola Parente , Magda Zanelli , Francesca Sanguedolce *, Luca Mastracci y 1, and Paolo Graziano y 1 Pathology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Ospedale Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, 71013 San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy; [email protected] (P.P.); [email protected] (P.G.) 2 Pathology Unit, Azienda USL-IRCCS Reggio Emilia, 42123 Reggio Emilia, Italy; [email protected] 3 Pathology Unit, Azienda Ospedaliera-Universitaria OO.RR, 71100 Foggia, Italy 4 Anatomic Pathology, Ospedale Policlinico San Martino IRCCS, 16132 Genova, Italy; [email protected] 5 Anatomic Pathology, Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics (DISC), University of Genova, 16132 Genova, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-0881736315 These Authors contributed equally. y Received: 10 September 2020; Accepted: 24 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Reed–Sternberg cells (RSCs) are hallmarks of classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). However, cells with a similar morphology and immunophenotype, so-called Reed–Sternberg-like cells (RSLCs), are occasionally seen in both B cell and T cell non-Hodgkin Lymphomas (NHLs). In NHLs, RSLCs are usually present as scattered elements or in small clusters, and the typical background microenviroment of cHL is usually absent. Nevertheless, in NHLs, the phenotype of RSLCs is very similar to typical RSCs, staining positive for CD30 and EBV, and often for B cell lineage markers, and negative for CD45/LCA. Due to different therapeutic approaches and prognostication, it is mandatory to distinguish between cHL and NHLs. Herein, NHL types in which RSLCs can be detected along with clinicopathological correlation are described. -

Hodgkin Lymphoma

Hodgkin Lymphoma Zach, Hodgkin lymphoma survivor Revised 2013 A Message From John Walter President and CEO of The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) believes we are living at an extraordinary moment. LLS is committed to bringing you the most up-to-date blood cancer information. We know how important it is for you to have an accurate understanding of your diagnosis, treatment and support options. An important part of our mission is bringing you the latest information about advances in treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma, so you can work with your healthcare team to determine the best options for the best outcomes. Our vision is that one day the great majority of people who have been diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma will be cured or will be able to manage their disease with a good quality of life. We hope that the information in this publication will help you along your journey. LLS is the world’s largest voluntary health organization dedicated to funding blood cancer research, education and patient services. Since 1954, LLS has been a driving force behind almost every treatment breakthrough for patients with blood cancers, and we have awarded almost $1 billion to fund blood cancer research. Our commitment to pioneering science has contributed to an unprecedented rise in survival rates for people with many different blood cancers. Until there is a cure, LLS will continue to invest in research, patient support programs and services that improve the quality of life for patients and families. We wish you well. John -

Stats KID 2003 Severity File

HCUP Summary Statistics Report: KID 2003 - SEVERITY File 1 Means of Continuous Data Elements 13:36 Wednesday, December 14, 2005 N Variable / Label N Miss Minimum Maximum Mean Std Dev HOSPID : HCUP hospital identification number 2984129 0 4001.00 55188.00 27728.13 15991.24 RECNUM : HCUP record number 2984129 0 1.00 6614217.0 3307312.6 1909855.8 APRDRG : All Patient Refined DRG 2984129 0 1.00 956.00 469.20 229.77 APRDRG_Risk_Mortality : All Patient Refined DRG: Risk of Mortality Subclass 2984129 0 0.00 4.00 1.11 0.43 APRDRG_Severity : All Patient Refined DRG: Severity of Illness Subclass 2984129 0 0.00 4.00 1.55 0.75 APSDRG : All-Payer Severity-adjusted DRG 2984129 0 10.00 9112.00 3277.30 1807.40 APSDRG_Charge_Weight : All-Payer Severity-adjusted DRG: Charge Weight 2984129 0 0.10 29.24 0.76 1.48 APSDRG_LOS_Weight : All-Payer Severity-adjusted DRG: Length of Stay Weight 2984129 0 0.22 18.97 0.92 1.31 APSDRG_Mortality_Weight : All-Payer Severity-adjusted DRG: Mortality Weight 2984129 0 0.00 36.44 0.33 1.46 CM_AIDS : AHRQ comorbidity measure: Acquired immune deficiency syndrome 2984129 0 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.01 CM_ALCOHOL : AHRQ comorbidity measure: Alcohol abuse 2984129 0 0.00 1.00 0.01 0.08 CM_ANEMDEF : AHRQ comorbidity measure: Deficiency anemias 2984129 0 0.00 1.00 0.02 0.15 CM_ARTH : AHRQ comorbidity measure: Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseases 2984129 0 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.04 CM_BLDLOSS : AHRQ comorbidity measure: Chronic blood loss anemia 2984129 0 0.00 1.00 0.01 0.11 CM_CHF : AHRQ comorbidity measure: Congestive heart failure -

The Pathology and Nomenclature of Hodgkin's Disease

ICANCER RESEARCH 26 Part 1, 1063-1081,June 1966] The Pathology and Nomenclature of Hodgkin's Disease ROBERT J. LUKES AND JAMES J. BUTLER Department of Pathology, University of Southern California, School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California (R. J. L.) and Department of Pathology, M. D. Anderson Hospital, Houston, Texas (J. J. B.) Summary relate the histologie features to survival and to depict the as yet The diverse morphologic expressions of Hodgkin's disease have unsettled nature of the basic process. Over SO terms for the disease were collected from the literature by Wallhauser (35) been reviewed and compared to the numerous histologie terms in from the 1st century after Thomas Hodgkin's description. This the literature and the author's recently proposed histologie profusion of names for the disease primarily reflects the different, types. The relationship of the histologie findings to the clinical concepts of the disease particularly in relationship to etiology. stages and survival has also been analyzed. The histologie ex pressions of the Hodgkin's disease process appear to be reparable The noncommittal eponymic designation has gained general acceptance in the United States at the present time, even though into the following 6 groups: (a) lymphocytic and/or histiocytic (L & H),1 nodular; (b) lymphocytic and/or histiocytic (L & H), the process is generally regarded as a neoplasm and included with the malignant lymphomas. In the past 4 decades numerous diffuse; (c) nodular sclerosis; (d) mixed; (e) diffuse fibrosis; and terms have been proposed for the histologie types of Hodgkin's. (/) reticular. The L & H types represent essentially a pre disease as a result of the attempts to relate the histologie changes dominant lymphocytic proliferation with histiocytes, while to the extremely variable rates of progression of the disease and diffuse fibrosis and reticular are associated with lymphocytic to provide a prognostic basis for the recognition of potential depletion. -

The Owl-Eyed, Herculean Cancroid- Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Cell Cellular

Cell & Cellular Life Sciences Journal ISSN: 2578-4811 The Owl-Eyed, Herculean Cancroid- Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Anubha B* Mini Review Histopathology and Cytopathology consultant, India Volume 3 Issue 2 Received Date: June 07, 2018 *Corresponding author: Anubha Bajaj, Histopathology and Cytopathology Published Date: July 03, 2018 consultant, New Delhi, India, Tel: 00911125117399; Email: [email protected] Abstract Initially scripted by Dr Thomas Hodgkin (1798-1866) in 1832, Hodgkin’s Lymphoma is a neoplasm, essentially disseminated in a predominantly non-malignant cell population the lymphoma comprises chiefly of T lymphocytes. The classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma (c HL) and the subtype lymphocyte predominance (NLPHD) commences with a B cell clone. The age predominance, surmises two definitive developments: i) A minimally infective agent contaminates the young adults and ii) A synergistic conformity of lymphomas that may explain the pathogenesis of adult Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) may be implicated in 30%-50% of the immune competent Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Array based comparative genomic hybridization (a CGH) may be applied to analyze the genes applicable in the pathogenesis of c HL. The Ann Arbor classification delineates the dominant prognostic categories as the LIMITED (EARLY STAGE) and ADVANCED DISEASE. The Early Stage includes the stage I and II while stage III and IV are encompassed in the Advanced Disease. Stage II along with the systemic symptoms (II B) may be incorporated in the subclass of UNFAVOURABLE Early Stage Disease. The mortality of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma has diminished considerably with the current 5 year survival rate at 81%. Where no therapy has been instituted, the survival extends to 1- 2 years with < 5% of patients existing at 5 years. -

ICD-O-3 Implementation Guidelines

North American Association of Central Cancer Registries GUIDELINES FOR ICD-O-3 IMPLEMENTATION Prepared by the NAACCR ICD-O-3 Implementation Work Group November 27, 2000 Guidelines for ICD-O-3 Implementation NAACCR, Inc TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 3 2 BACKGROUND AND IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES....................................................................... 4 2.1 Why ICD-O-3? ........................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 How sweeping is the change? ..................................................................................................... 4 2.3 When will the ICD-O-3 manual be available? ............................................................................ 4 2.4 What about training for data collectors? ..................................................................................... 4 2.5 What impact does the delayed release of the ICD-O-3 manual have on case finding on or after January 1, 2001? ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2.6 What impact does the delayed release of the ICD-O-3 manual have on cancer registry software development and release? ........................................................................................................................ 5 2.7 What are the conversion issues? -

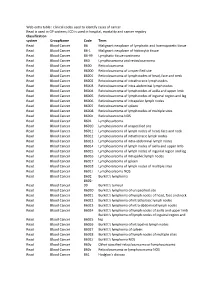

Web Extra Table : Clinical Codes Used to Identify Cases of Cancer Read Is

Web extra table : clinical codes used to identify cases of cancer Read is used in GP systems; ICD is used in hospital, mortality and cancer regsitry Classification system GroupName Code Term Read Blood Cancer B6 Malignant neoplasm of lymphatic and haemopoietic tissue Read Blood Cancer B6-1 Malignant neoplasm of histiocytic tissue Read Blood Cancer B6-99 Lymphatic tissue carcinoma Read Blood Cancer B60 Lymphosarcoma and reticulosarcoma Read Blood Cancer B600 Reticulosarcoma Read Blood Cancer B6000 Reticulosarcoma of unspecified site Read Blood Cancer B6001 Reticulosarcoma of lymph nodes of head, face and neck Read Blood Cancer B6002 Reticulosarcoma of intrathoracic lymph nodes Read Blood Cancer B6003 Reticulosarcoma of intra-abdominal lymph nodes Read Blood Cancer B6004 Reticulosarcoma of lymph nodes of axilla and upper limb Read Blood Cancer B6005 Reticulosarcoma of lymph nodes of inguinal region and leg Read Blood Cancer B6006 Reticulosarcoma of intrapelvic lymph nodes Read Blood Cancer B6007 Reticulosarcoma of spleen Read Blood Cancer B6008 Reticulosarcoma of lymph nodes of multiple sites Read Blood Cancer B600z Reticulosarcoma NOS Read Blood Cancer B601 Lymphosarcoma Read Blood Cancer B6010 Lymphosarcoma of unspecified site Read Blood Cancer B6011 Lymphosarcoma of lymph nodes of head, face and neck Read Blood Cancer B6012 Lymphosarcoma of intrathoracic lymph nodes Read Blood Cancer B6013 Lymphosarcoma of intra-abdominal lymph nodes Read Blood Cancer B6014 Lymphosarcoma of lymph nodes of axilla and upper limb Read Blood Cancer B6015