Happiness and the Psalms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philosophy of Happiness: an Interdisciplinary Introduction

“This outstanding book is the introduction to happiness many of us have been waiting for: Clear and accessible, engaging, and remarkably comprehensive. It covers not just the philosophy of happiness but also the science, economics, and policy side of happiness, as well as practical issues about how to be happier, and includes non-Western approaches as well. It is the single best overview of research on happiness, and I strongly recommend it both for the classroom and for researchers wanting to learn more about the field, as well as anyone wishing to understand the state of the art in thinking about happiness.” Daniel M. Haybron, Saint Louis University “An engaging and wide-ranging introduction to the study of happiness. The book’s perspective is philosophical, and it would be an excellent choice for philosophy courses in ethics or happiness itself. The philosophy here is enriched by well-informed discussions of research in psychology, neuroscience, and economics, which makes it a very fine choice for courses in any field where there is an interest in a philosopher’s take on happiness. Indeed, anyone with an interest in happiness—whether or not they are teaching or taking a course—would profit from reading this book. Highly recommended!” Valerie Tiberius, University of Minnesota THE PHILOSOPHY OF HAPPINESS Emerging research on the subject of happiness—in psychology, economics, and public policy—reawakens and breathes new life into long-standing philosophi- cal questions about happiness (e.g., What is it? Can it really be measured or pursued? What is its relationship to morality?). By analyzing this research from a philosophical perspective, Lorraine L. -

Giovanni Paolo Colonna "Psalmi Ad Vesperas" Op. 12: Introduction

GIOVANNI PAOLO COLONNA Psalmi ad Vesperas OPUS DUODECIMUM, 1694 Edited by Pyrros Bamichas May 2010 WEB LIBRARY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MUSIC (www.sscm-wlscm.org), WLSCM No. 18 Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... iii The Composer ........................................................................................................................ iii The Music .............................................................................................................................. vi Liturgical Practice .................................................................................................................. xi Acknowledgments................................................................................................................. xii CRITICAL COMMENTARY ..................................................................................................... xiv The Sources .......................................................................................................................... xiv Other Sources for the Pieces of Op. 12 .............................................................................. xviii Editorial Method ................................................................................................................... xx Critical Notes ....................................................................................................................... xxi [1] Domine ad adjuvandum -

Cultural Values and Happiness: an East–West Dialogue

The Journal of Social Psychology, 2001, 141(4), 477–493 Cultural Values and Happiness: An East–West Dialogue LUO LU Graduate Institute of Behavioural Sciences Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan ROBIN GILMOUR Department of Psychology University of Lancaster, United Kingdom SHU-FANG KAO Graduate Institute of Behavioural Sciences Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan ABSTRACT. Happiness as a state of mind may be universal, but its meaning is complex and ambiguous. The authors directly examined the relationships between cultural values and experiences of happiness in 2 samples, by using a measurement of values derived from Chinese culture and a measurement of subjective well-being balanced for sources of happiness salient in both the East and the West. The participants were university stu- dents—439 from an Eastern culture (Taiwan) and 344 from a Western culture (the United Kingdom). Although general patterns were similar in the 2 samples, the relationships between values and happiness were stronger in the Taiwanese sample than in the British sample. The values social integration and human-heartedness had culture-dependent effects on happiness, whereas the value Confucian work dynamism had a culture-general effect on happiness. Key words: British university students, Eastern cultural values, happiness, Taiwanese uni- versity students, Western cultural values FOR CENTURIES, scholars in many disciplines have studied happiness, or sub- jective well-being (SWB), and have defined it in ethical, theological, political, economic, and psychological terms (Diener, 1984; Veenhoven, 1984). Happiness is currently defined (a) as a predominance of positive over negative affect and (b) as satisfaction with life as a whole (Argyle, Martin, & Crossland, 1989; Diener). -

Worship God Reverently, Great and Small

Second Vespers in Ordinary Time e Week IV f ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL SEATTLE Second Vespers WITH BENEDICTION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT FOR THE SUNDAYS OF ORDINARY TIME Week IV We welcome our visitors to St. James Cathedral and to Sunday Vespers. In keeping with a long tradition in cathedral churches, the Office of Vespers, along with Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, is prayed each Sunday in the cathedral, linking St. James with cathedral churches throughout the world. We invite your prayerful participation. Lucernarium OFFERING OF LIGHT please stand Cantor: ALL: Procession from the Paschal Candle Cantor: ALL: all make the sign of the cross The cantor proclaims the evening thanksgiving, which ends: ALL: Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament INCENSATION AND SONG please kneel Psalm 141 Domine, clamavi Refrain Hughes Cantor: I have called to you, Lord: hasten to help me! Hear my voice when I cry to you. Let my prayer arise before you like incense, the raising of my hands like an evening oblation. Refrain. Set, O Lord, a guard over my mouth; keep watch at the door of my lips! Do not turn my heart to things that are wrong, to evil deeds with those who are sinners. Refrain Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit: as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be for ever. Amen. Refrain Presider: Let us pray. Collect to Psalm 141 ALL: Amen. Evening Hymn O gladsome light nunc dimittis Psalmody From ancient times it has been the custom the pray the Psalms antiphonally. -

The Twenty-Third Day at Morning Prayer

The Twenty-third Day at Morning Prayer PSALM 110 Dixit Dominus Tone III A 2 THE LORD said / unto my Lord, * Sit thou on my right hand, until I make thine ene/mies thy footstool. 2. The Lord shall send the rod of thy power / out of Zion: * be thou ruler, even in the midst a/mong thine enemies. 3. In the day of thy power shall thy people offer themselves willingly with an / holy worship: * thy young men come to thee as dew from the womb / of the morning. 4. The Lord / sware, and will not repent, * Thou art a Priest for ever after the order / of Melchizedek. 5. The Lord u/pon thy right hand * shall wound even kings in the / day of his wrath. 6. He shall judge a/mong the heathen; * he shall fill the places with the dead bodies, and smite in sunder the heads over / divers countries. 7. He shall drink of the / brook in the way; * therefore shall he / lift up his head. Glory be to the / Father, and to the Son, * and / to the Holy Ghost: As it was in the beginning, † is now, and / ever shall be, * world / without end. Amen. PSALM 111 Confitebor tibi Tone IV 8 I WILL give thanks unto the Lord with / my whole heart, * secretly among the faithful, and in the con/gregation. 2. The works / of the Lord are great, * sought out of all them that have plea/sure therein. 3. His work is worthy to be praised and / had in honor, * and his righteousness endureth / for ever. -

Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person Quarter 2 - Module 8: the Meaning of His/Her Own Life

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Regional Office IX, Zamboanga Peninsula 12 Zest for Progress Zeal of Partnership Introduction to the Philosophy of the Human Person Quarter 2 - Module 8: The Meaning of His/Her Own Life Name of Learner: ___________________________ Grade & Section: ___________________________ Name of School: ___________________________ WHAT I NEED TO KNOW? An unexamined life is a life not worth living (Plato). Man alone of all creatures is a moral being. He is endowed with the great gift of freedom of choice in his actions, yet because of this, he is responsible for his own freely chosen acts, his conduct. He distinguishes between right and wrong, good and bad in human behavior. He can control his own passions. He is the master of himself, the sculptor of his own life and destiny. (Montemayor) In the new normal that we are facing right now, we can never stop our determination to learn from life. ―Kung gusto nating matuto maraming paraan, kung ayaw naman, sa anong dahilan?‖ I shall present to you different philosophers who advocated their age in solving ethical problems and issues, besides, even imparted their age on how wonderful and meaningful life can be. Truly, philosophy may not teach us how to earn a living yet, it can show to us that life is worth existing. It is evident that even now their legacy continues to create impact as far as philosophy and ethics is concerned. This topic: Reflect on the meaning of his/her own life, will help you understand the value and meaning of life since it contains activities that may help you reflect the true meaning and value of one’s living in a critical and philosophical way. -

Some Historical Perspectives on the Monteverdi Vespers

CHAPTER V SOME HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE MONTEVERDI VESPERS It is one of the paradoxes of musicological research that we generally be- come acquainted with a period, a repertoire, or a style through recognized masterworks that are tacitly or expressly assumed to be representative, Yet a masterpiece, by definition, is unrepresentative, unusual, and beyond the scope of ordinary musical activity. A more thorough and realistic knowledge of music history must come from a broader and deeper ac- quaintance with its constituent elements than is provided by a limited quan- tity of exceptional composers and works. Such an expansion of the range of our historical research has the advan- tage not only of enhancing our understanding of a given topic, but also of supplying the basis for comparison among those works and artists who have faded into obscurity and the few composers and masterpieces that have sur- vived to become the primary focus of our attention today. Only in relation to lesser efforts can we fully comprehend the qualities that raise the master- piece above the common level. Only by comparison can we learn to what degree the master composer has rooted his creation in contemporary cur- rents, or conversely, to what extent original ideas and techniques are re- sponsible for its special features. Similarly, it is only by means of broader investigations that we can detect what specific historical influence the mas- terwork has had upon contemporaries and younger colleagues, and thereby arrive at judgments about the historical significance of the master com- poser. Despite the obvious importance of systematic comparative studies, our comprehension of many a masterpiece stiIl derives mostly from the artifact itself, resulting inevitably in an incomplete and distorted perspective. -

Henryk Górecki's Spiritual Awakening and Its Socio

DARKNESS AND LIGHT: HENRYK GÓRECKI’S SPIRITUAL AWAKENING AND ITS SOCIO-POLITICAL CONTEXT By CHRISTOPHER W. CARY A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Christopher W. Cary ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Christopher Caes, who provided me with a greater understanding of Polish people and their experiences. He made the topic of Poland’s social, political, and cultural history come alive. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Paul Richards and Dr. Arthur Jennings for their scholarly ideas, critical assessments, and kindness. I would like to thank my family for their enduring support. Most importantly, this paper would not have been possible without Dr. David Kushner, my mentor, friend, and committee chair. I thank him for his confidence, guidance, insights, and patience. He was an inspiration for me every step of the way. Finally, I would like to thank Dilek, my light in all moments of darkness. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 Purpose of the Study.....................................................................................................1 -

Early Jewish Writings

EARLY JEWISH WRITINGS Press SBL T HE BIBLE AND WOMEN A n Encyclopaedia of Exegesis and Cultural History Edited by Christiana de Groot, Irmtraud Fischer, Mercedes Navarro Puerto, and Adriana Valerio Volume 3.1: Early Jewish Writings Press SBL EARLY JEWISH WRITINGS Edited by Eileen Schuller and Marie-Theres Wacker Press SBL Atlanta Copyright © 2017 by SBL Press A ll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office,S BL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schuller, Eileen M., 1946- editor. | Wacker, Marie-Theres, editor. Title: Early Jewish writings / edited by Eileen Schuller and Marie-Theres Wacker. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, [2017] | Series: The Bible and women Number 3.1 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers:L CCN 2017019564 (print) | LCCN 2017020850 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142324 (ebook) | ISBN 9781628371833 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780884142331 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Bible. Old Testament—Feminist criticism. | Women in the Bible. | Women in rabbinical literature. Classification: LCC BS521.4 (ebook) | LCC BS521.4 .E27 2017 (print) | DDC 296.1082— dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019564 Press Printed on acid-free paper. -

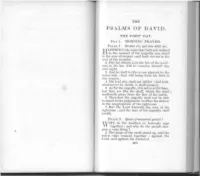

Psalms of Da Vid

THE PSALMS OF DA VID. THE FIRST DAY. DAY 1. MORNING PRAYER. PSALM 1. Beatus vir, qui non abiit &c. LESSED is the man that hath not walked B in the counsel of the ungodly, nor stood in the way of sinners: and hath not sat in the seat of the scornful. 2 But his delight is in the law of the Lord: and in his law will he exercise himself day and night. 3 And he shall be like a tree planted by the water-side: that will bring forth his fruit in due season. 4 His leaf also shall not wither: and look, whatsoever he doeth, it shall prosper. 5 As for the ungodly, it is not so with them: but they are like the chaff, which the wind scattereth away from the face of the earth. 6 Therefore the ungodly shall not be able to stand in the judgement: neither the sinners in the congregation of the righteous. 7 But the Lord knoweth the way of the righteous : and the way of the ungodly shall perish. PSALM 2. Quare fremuerunt gentes? "llTHY do the heathen so furiously rage VV together: and why do the people ima gine a vain thing ? 2 The kings of the earth stand up, and the rulers take counsel together : against the Lord, and against his Anointed. 405 DAY 1: MN. THE PSALl\IS. PS. 3. PSS. 4,5. THE PSALMS. DAY 1: MN. 3 Let us break their bonds asunder : and the people: that have set themselves against cast away their cords from us. -

Sexagesima SEVENTH of FEBRUARY, A.D

OMAHA, NEBRASKA SAINT BARNABAS CHURCH A ROMAN CATHOLIC PARISH OF THE Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter EVENSONG AND BENEDICTION OF THE BLESSED SACRAMENT Sexagesima SEVENTH of FEBRUARY, a.d. 2021 Preces sung by the Ritual Choir O Lord, open thou our lips. And our mouth shall shew forth thy praise. O God, make speed to save us. O Lord, make haste to help us. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be world without end. Amen. Praise ye the Lord The Lord’s name be praised. Psalmody Psalm 111 (110) Confitebor tibi Tone iv will give thanks unto the Lord |with my whole heart: sit I secretly among the faithful, and in |the congregation. 2 The works |of the Lord are great: sought out of all of them that |have pleasure therein. 3 His work is worthy to be praised and |had in honour: and his righteousness en-|dureth for ever. 4 The merciful and gracious Lord hath so |done his marvellous works: that they ought to be |had in remembrance. 5 He hath given meat unto |`them that fear him: he shall ever be mind-|ful of his covenant. 6 He hath shewed his people the power |of his works: that he may give them the heri-|tage of the heathen. 7 The works of his hands are veri-|ty and judgment: all his |commandments are true. 8 They stand fast for ev-|er and ever: and are done |in truth and equity. -

Philosophy of Happiness Regents Professor Julia Annas

Philosophy 220: Philosophy of Happiness Regents Professor Julia Annas. MWF 1 – 1.50 pm. Chavez 301. The course has a D2L website, where all the readings are to be found. My office is Social Science Building 123. Office hours TBA. The Philosophy Department office is Social Sciences Building 213. Why happiness? Happiness matters!. There are large numbers of self-help books telling us how to be happy. Some nations are planning to measure the happiness of their citizens to find out how it can be increased. There is a huge field of ‘happiness studies’, and focus on happiness in positive psychology as well as politics and law. Much of this is confusing, since it’s often not clear what the authors think happiness is. Is it feeling good? Is it having a positive attitude to the way you are now? Is it having a positive attitude to your life as a whole? Is it having a happy life? How can some people advise others on how to be happy? Philosophers have explored happiness, and our search for happiness, for two thousand years. They have asked what happiness is, and have developed different answers, including some now being rediscovered. In this course we will ask what happiness is, and look at major answers. We’ll look at rich philosophical traditions of thinking about happiness, and also at some recent work in the social sciences. We’ll examine the contributions being made to the ongoing search to find out what happiness is, and how we can live happy lives. Course Readings Course readings will be available on the D2L site.