Nicaraguan Women: Unlearning the Alphabet of Submission Was Made Possible in Part by Fund- Ing from W.H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

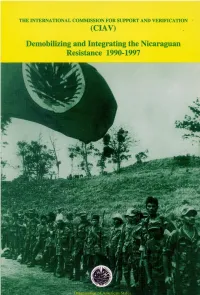

Demobilizing and Integrating the Nicaraguan Resistance 1990-1997

The International Commission for Support and Verification Commission (CIAV) Demobilizing and Integrating the Nicaraguan Resistance 1990-1997 ii Acknowledgements: This paper is a summary English version, written by Fernando Arocena, a consultant to CIAV-OAS, based on the original Spanish report: “La Comisión Internacional de Apoyo y Verificación, La Desmovilización y Reinserción de la Resistencia Nicaragüense 1990 – 1997”, prepared by Héctor Vanolli, Diógenes Ruiz and Arturo Wallace, also consultants to the CIAV-OAS. Bruce Rickerson, Senior Specialist at the UPD revised and edited the English text. This is a publication of the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States. The ideas, thoughts, and opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the OAS or its member states. The opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors. Correspondence should be directed to the UPD, 1889 "F" Street, N.W., 8th Floor, Washington, DC, 20006, USA. Copyright ©1998 by OAS. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced provided credit is given to the source. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS................................................................................................................................ix READER'S GUIDE ..................................................................................................................... xi INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................xiii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... -

A Nicaraguan Exceptionalism? Debating the Legacy of the Sandinista Revolution

A Nicaraguan Exceptionalism? Debating the Legacy of the Sandinista Revolution edited by Hilary Francis INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES A Nicaraguan Exceptionalism? Debating the Legacy of the Sandinista Revolution edited by Hilary Francis Institute of Latin American Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2020 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/. This book is also available online at http://humanities-digital-library.org. ISBN: 978-1-908857-57-6 (paperback edition) 978-1-908857-78-1 (.epub edition) 978-1-908857-79-8 (.mobi edition) 978-1-908857-77-4 (PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/220.9781908857774 (PDF edition) Institute of Latin American Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House London WC1E 7HU Telephone: 020 7862 8844 Email: [email protected] Web: http://ilas.sas.ac.uk Typesetting by Thomas Bohm, User Design, Illustration and Typesetting. Cover image © Franklin Villavicencio. Contents List of illustrations v Notes on contributors vii Introduction: exceptionalism and agency in Nicaragua’s revolutionary heritage 1 Hilary Francis 1. ‘We didn’t want to be like Somoza’s Guardia’: policing, crime and Nicaraguan exceptionalism 21 Robert Sierakowski 2. ‘The revolution was so many things’ 45 Fernanda Soto 3. Nicaraguan food policy: between self-sufficiency and dependency 61 Christiane Berth 4. On Sandinista ideas of past connections to the Soviet Union and Nicaraguan exceptionalism 87 Johannes Wilm 5. -

La Retórica Del Placer: Cuerpo, Magia, Deseo Y Subjetividad En Cinco Novelas De Gioconda Belli

La Retórica del Placer: Cuerpo, Magia, Deseo y Subjetividad en Cinco Novelas de Gioconda Belli Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Urzúa-Montoya, Miriam Rocío Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 09:25:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/238652 1 LA RETÓRICA DEL PLACER: CUERPO, MAGIA, DESEO Y SUBJETIVIDAD EN CINCO NOVELAS DE GIOCONDA BELLI by Miriam Rocío Urzúa-Montoya _____________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN SPANISH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2012 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Miriam Rocío Urzúa-Montoya entitled La retórica del placer: Cuerpo, magia, deseo y subjetividad en cinco novelas de Gioconda Belli and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: May 16, 2012 Laura G. Gutiérrez _______________________________________________________________________ Date: May 16, 2012 Melissa A. Fitch _______________________________________________________________________ Date: May 16, 2012 Amy R. Williamsen Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Twentieth Century Nicaraguan Protest Poetry: the Struggle for Cultural Hegemony

KU ScholarWorks | The University of Kansas Central American Theses and Dissertations Collection http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Twentieth Century Nicaraguan Protest Poetry: The Struggle for Cultural Hegemony by Kenneth R. Kincaid M.A., University of Kansas, 1994 Professor in Charge Charles Stansifer Committee Members Vicky Unruh Elizabeth Kuznesof The University of Kansas has long historical connections with Central America and the many Central Americans who have earned graduate degrees at KU. This work is part of the Central American Theses and Dissertations collection in KU ScholarWorks and is being made freely available with permission of the author through the efforts of Professor Emeritus Charles Stansifer of the History department and the staff of the Scholarly Communications program at the University of Kansas Libraries’ Center for Digital Scholarship. TWENTETH CENTURY NiCAR AGUAN PROTEST POETRY: THE STRUGGLE FOR CULTURAL HEGEMONY ay * KitK>*fl) TWENTIETH CENTURY NIGARAGUAN PROTEST POETRY: THE STRUGGLE FOR CULTURAL HEGEMONY by Kenneth R. ^ncaid M.A., University of' Kansas, 1994 Submitted to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in par• tial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Latin American History. / Charles Stansifer \j \ - : Vic^y Unruh Elizabeth Kuznesof For the Graduate Division Date thesis accepted RGOSST fifiMflS 5 Abstract The 1979 Nicaraguan revolution spawned many demo• cratic reforms. These included agrarian, political, economic and cultural changes that were implemented in order to increase participation in all aspects of Nicara• guan life. Of the changes, one would have to consider those effecting culture and poetry to be the most unique. -

Panel 10: Testimonial Writing Across the Americas Moderator: Patrick D

IABAA 2017 – Lives Outside the Lines: A Symposium in Honour of Marlene Kadar Panel 10: Testimonial Writing Across the Americas Moderator: Patrick D. M. Taylor Lisa Ortiz-Vilarelle, The College of New Jersey [[email protected]] Milk Poems and Blood Poems: Autobiographical Poetry and the New Nicaraguan Woman In 1967, La Prensa Literaria, Nicaragua’s most highly regarded literary magazine, laments that Nicaragua is “overpopulated” by “poetesses” who outnumber male poets 1,000 to 700 in the capital alone. Nicaraguan women were virtually invisible in their nation’s literary history until the future of a revolutionary “new Nicaragua” was being imagined by an idealist, nationalist, socialist, but not always feminist, Sandinista movement. Through the literary magazines founded by the Sandinista National Liberation Front, these spokeswomen and activists published transformative autobiographical poetry chronicling the aesthetic, social, and political birth of the “new woman” in Nicaragua. This poetry introduced a new voice – that of a self-reflective revolutionary womanhood. The focus of this paper is the construction Sandinista womanhood through its autobiographical depiction in a full range of embodied self- expression. This paper will examine the poetry of six influential guerilla poets of the revolution – Daisy Zamora, Gioconda Belli, Yolanda Blanco, Michele Najlis, Vidaluz Meneses, and Rosario Murillo, wife of Sandinista leader and president of Nicaragua, Daniel Ortega – all of whom vocalize the emergence of the “New Nicaraguan Woman” as experienced in the physical body. Unapologetically presented in cycles of menstruation, states of pregnancy, labor of childbirth, and climaxes of erotic ecstasy, these poets challenge the bourgeois chivalry of the ruling class for which graphic references to the female body are considered indecent. -

UN Digital Library

UNITED *-7’; NATIONS q -c L S PROVISIONAL S/PV.2792 17 February 1988 ENGLISH PROVISIONAL VERBATIM RECORD OF THE TWO THOUSAND SEVEN HUNDRED AND NINETY-SECOND MEETING Held at Headcuarters, New York, on Wednesday, 17 February 1988, at 10.30 a.m. President: Mr. WALTERS (United States of America) Members: Algeria Mr. ACHACHE Argentina Mr. DELPECH Brazil Mr. ALLENCAR China Mr. LI LUye France Mr. BLANC -_ -Germany, Federal Republic of Mr. VERGAU Italy Mr. BUCCI Japan Mr. KAGAMI Nepal Mr. RANA Senegal Mr. SARRE Union of Soviet Socialist Republics Mr. BELONOGOV United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Mr. BIRCH Yugoslavia Mr. PEJIC Zambia Mr. ZUZE This record contains the original text of speeches delivered in English and interpretations of speeches in the other languages. The'final~text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to original speeches only. They should be &R?:nx~u&&r the signature of a member of the delegation concerned, within one week, to the Chief, Official Records Editing Section, Department of Conference Services, tbbm DC&750, 2 United Nations Plaza, and incorporated in a copy of the record. 88-6U286A 3286V (E) 2-d . 3 ..'. RW3 S/PV.2792 &&pi 2-5 The meeting was called to order a-t lo,55 a..m. ADOP.l!IONOF TBE AGENDA The agenda was adopted. LETTER DATED 18FEBRUARY 1988 FRa TBE PERMANENTOBSERVER OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA TD THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED 'ID THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY CXINCIL (s/19488) =m DATED 18 FEBRUARY 1988 FRW THE PERMANENT REPRESENTATIVE OF JAPAN 'IO THE UNITED NATIONS ADDRESSED IO THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY CDUNCIL (S/19489) The PRESIDENT: In accordance with decisions taken by the Council at its 2791st meeting, I invite the representative of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and the \ representative of the Republic of Korea to take places at the Council table. -

THE EROTICIZED FEMINISM of GIOCONDA BELLI Elizabeth

SPEAKING THROUGH THE BODY: THE EROTICIZED FEMINISM OF GIOCONDA BELLI Elizabeth Casimir Bruno A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (Spanish American) Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: María A. Salgado Reader: Rosa Perelmuter Reader: Glynis Cowell Reader: Teresa Chapa Reader: John Chasteen © 2006 Elizabeth Casimir Bruno ii ABSTRACT ELIZABETH CASIMIR BRUNO: Speaking Through the Body: The Eroticized Feminism of Gioconda Belli (Under the direction of María A. Salgado) While female authors have been writing about “women’s issues” for centuries, their foregrounding of women’s bodies is a relatively new phenomenon. This “literature of the body” is perceived as a way for women to claim back what is and has always been theirs. Gioconda Belli’s literature of the body presents a mosaic of images of woman, through which she empowers women to claim back their body and to celebrate it as the site of the multiple facets of woman. After a brief introductory chapter presenting my topic, I move to Chapter 2, which explores how Belli embodies “woman” in her poetry. In order to contextualize her representation, I first look at several poems by Rubén Darío as examples of idealized canonical portrayals. I also analyze poems written by a number of women authors who preceded Belli, thereby demonstrating a distinct progression in the treatment of women-centered literature. Belli’s representation of the erotic woman is the focus of Chapter 3, though I also examine some poems by another Central American woman poet that illustrate the boldness of her work, particularly because this author was the first Central American woman writer to celebrate women’s eroticism. -

El País De Las Mujeres De Gioconda Belli: Um Romance Feminista?

Bruna Bechlin Queiroz Lopes El país de las mujeres de Gioconda Belli: Um romance feminista? Dissertação de Mestrado em Estudos Literários e Culturais, orientada pela Doutora Catarina Isabel Caldeira Martins, apresentada ao Departamento de Línguas, Literaturas e Culturas da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra 2016 Faculdade de Letras El país de las mujeres de Gioconda Belli: Um romance feminista? Ficha Técnica: Tipo de trabalho Dissertação de Mestrado Título EL PAÍS DE LAS MUJERES, DE GIOCONDA BELLI: UM ROMANCE FEMINISTA? Autora Bruna Bechlin Orientadora Catarina Martins Júri Presidente: Doutor Apolinário Lourenço 1. Doutora Isabel Caldeira 2. Doutora Catarina Martins Identificação do 2º Ciclo em Mestrado em Estudos Curso Literários e Culturais Área científica Letras Especialidade/Ramo Estudos Literários e Culturais Data da defesa 05-07-2016 Classificação 14 valores We cannot all succeed when half of us are held back. Malala Yousafzai I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own. Audre Lorde If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. Desmond Tutu We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time. T. S. Elliot 2 Agradecimentos Dividir a vida entre Portugal e Brasil foi muito difícil, aqui sentimos saudade da família, dos amigos, dos bichinhos de estimação e das festinhas que fazemos sempre que chegamos a casa, mas lá também sentimos saudade das companheiras de aula, dos sotaques variados, das diversas possibilidades que temos quando moramos sozinha em uma nova cidade. -

An Abstract of the Thesis of Kim Glover for the Master Ofarts in World

An Abstract Of The Thesis Of Kim Glover for the Master ofArts in World History presented on April 30, 2003 Title: The Revolutionary Women ofNicaragua Abstract approved:9" A c5~ This thesis contends that women were active participants in the revolutionary events taking place in Nicaragua between the 1960s through the 1990s. I state in this thesis that women made huge contributions and sacrifices on both sides ofthe Nicaraguan civil war in order to take a part in determining the government oftheir country and to develop a better future for themselves and others. The first chapter ofthis thesis will explain the events leading up to the Sandinista Revolution and the participation of women in the revolt. In chapter 2, in addition to a general overview ofwomen's involvement in the Nicaraguan revolution the thesis will also briefly compare it to the women's involvement in the Cuban revolution years earlier. In the next chapter I will also give personal accounts of several women that fought in the Sandinista revolution and ofthose that fought in the Contra counter-revolution. I have tried to include profiles ofwomen from different social classes and ofthose who fought in either support or combat situations. Chapter 4 ofthe thesis explains the Catholic Church's involvement in recruitment and organization of Sandinista and Contra revolutionaries with an emphasis on the Church's impact on women's involvement in the FSLN (Frente Sandinista de Liberaci6n Nacional). Chapter 5 will list and describe the different women's organizations that formed during the Sandinista revolution and after as well as their effects on women's lives in Nicaragua. -

De Sandino Aux Contras Formes Et Pratiques De La Guerre Au Nicaragua

De Sandino aux contras Formes et pratiques de la guerre au Nicaragua Gilles Bataillon De 1978 à 1987, la vie politique nicaraguayenne a été marquée par la prédomi- nance des affrontements armés. Le pays a en effet connu deux guerres civiles. La première opposa de 1978 à juillet 1979 le Front sandiniste de libération nationale (FSLN), le Conseil supérieur de l’entreprise privée (COSEP), le Parti conserva- teur, les sociaux-chrétiens et les communistes, les syndicalistes de toutes obé- diences à Anastasio Somoza Debayle et ses partisans et pris fin avec la défaite du dictateur. La seconde mit aux prises de 1982 à 1987 le nouvel État dominé par les sandinistes à une nébuleuse d’opposants, la Contra, composée de dissidents du sandinisme, d’anciens partisans de Somoza et de l’organisation indienne de la côte Caraïbe. Ces deux guerres se traduisirent par des affrontements particuliè- rement meurtriers entre les groupes armés, mais les populations civiles ne furent jamais à l’abri des cruautés des différents clans combattants, bien au contraire. Chacune de ces guerres civiles vit les parties en présence faire largement appel à l’aide étrangère. Enfin, les motifs religieux furent étroitement imbriqués aux motifs politiques. Deux interprétations de ces guerres ont été avancées. L’une met l’accent sur les facteurs internes, tant sociaux que politiques ; l’autre souligne le rôle décisif des interventions extérieures. La première, à laquelle est associé le nom d’Edelberto Que soient remerciés Jorge Alanı´z Pinell, Antonio Annino et Jean Meyer, dont les suggestions m’ont permis d’améliorer les premières versions de ce texte, fruit d’une recherche conduite au CIDE (Mexico). -

Teaching Central America

Central America: An Introductory Lesson By Pat Scallen Background The grand narrative of Latino immigrant history in the United States has most often settled upon Mexicans, who make up the overwhelming majority of Latino migrants in the past half century. Yet many rural areas, mid-sized cities, and even large metropolitan areas boast rapidly rising immigrant populations from the countries of Central America: Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. According to the 2010 Census, approximately 4 million people in the United States claim Central American origin, more than double the number recorded in 2000.1 In the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area, the Central American population has skyrocketed in recent years, dwarfing other immigrant populations.2 This rapid rise in the Central American population is reflected in area public schools; in the District, Spanish-speaking populations make up the majority or a significant minority of the student body at several elementary, middle, and high schools. Immediate reasons for the rapid increase in Central Americans crossing the U.S. border abound; high levels of poverty brought on by economic stagnation, political unrest, and violence are often cited as the most significant incentives to attempt the dangerous trek northward.3 But many of the problems which currently plague Central America are rooted in centuries of structural economic inequality, state-sponsored oppression, and institutionalized racism. This lesson is designed to introduce students to several of these concepts through brief biographical sketches of figures in twentieth-century Central American history. It then builds upon this knowledge in examining the role the United States has played in the affairs of these smaller nations residing in what many U.S. -

S Ijfsta REVOLUTION

NEWS COVE~AGE S iJfsTA REVOLUTION NEWS COVE~AGE REVOLUTION By Joshua Muravchik With a foreword by Pablo Antonio Cuadra, Editor ofLA PRENSA American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research Washington, D.C. Distributed to the Trade by National Book Network, 15200 NBN Way, Blue Ridge Summit, PA 17214. To order call toll free 1-800-462-6420 or 1-717-794-3800. For all other inquiries please contact the AEI Press, 1150 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 or call 1-800-862-5801. Publication of this volume is made possible by a grant from the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, Inc. Distributed by arrangement with UPA, Inc. 4720 Boston Way 3 Henrietta Street Lanham, MD 20706 London WC2E 8LU England ISBN 0-8447-3661-9 (alk. paper) ISBN 0-8447-3662-7 (pbk.: alk. paper) AEI Studies 476 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Muravchik, Joshua. News coverage of the Sandinista revolution / Joshua Muravchik. p. cm. - (AEI studies; 476) Includes bibliographies. ISBN 0-8447-3661-9 (alk. paper). ISBN 0-8447-3662-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Foreign news-United States-History. 2. Press and politics United States-History. 3. Nicaragua-Politics and government-1937-1979. 4. Nicaragua-History-Revolution, 1979. 5. Public opinion-United States. 6. Nicaragua-History Revolution, 1979-Foreign public opinion, American. I. Title. II. Series. PN4888.F69M87 1988 972.85'052-dcI9 88-10553 CIP © 1988 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Re search, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publica tion may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews.