Zero Dark Thirty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

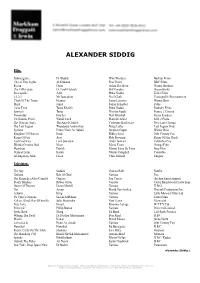

Alexander Siddig

ALEXANDER SIDDIG Film: Submergence Dr Shadid Wim Wenders Backup Films City of Tiny Lights Al-Dabaran Pete Travis BBC Films Recon Omar Adam Davidson Warner Brothers The Fifth Estate Dr Tarek Haliseh Bill Condon DreamWorks Inescapable Adib Ruba Nadda Killer Films 4.3.2.1 Mr Jauo-pinto Noel Clark Unstoppable Entertainment Clash Of The Titans Hermes Louis Leterrier Warner Bros Miral Jamal Julian Schnabel Pathe Cairo Time Tareq Khalifa Ruba Nadda Foundry Films Spy(ies) Tariq Nicolas Saada France 2 Cinema Doomsday Hatcher Neil Marshall Focus Features Un Homme Perdi Wahid Saleh Danielle Arbid M K 2 Prods. The Nativity Story The Angel Gabriel Catherine Hardwicke New Line Cinema The Last Legion Theodorus Andronikos Doug Lefler Last Legion Prod Syriana Prince Nasir Al- Subaii Stephen Gagan Warner Bros Kingdom Of Heaven Imad Ridley Scott 20th Century Fox Reign Of Fire Ajay Rob Bowman Reign Of Fire Prods. Last First Kiss Lord Sebastian Andy Tennant Columbia Pics World's Greatest Dad Nisse Maria Essen Omega Film Heartbeat Patrick Martin Lima De Faria Stop Film Vertical Limit Karim Martin Campbell Columbia A Dangerous Man Faisal Chris Menaul Enigma Television: The Spy Sudaini Gideon Raff Netflix Gotham Ra's Al Ghul Various Fox The Kennedys After Camelot Onassis Jon Cassar Asylum Entertainment Peaky Blinders Ruben Oliver Various Caryn Mandabach Productions Game Of Thrones Doran Martell Various H B O Tut Amun David Von Ancken Pharaoh Productions Inc. Atlantis King Various Little Monster Films Ltd Da Vinci's Demons Saslan Al Rahim Various Tonto Films Falcon; -

Pastor's Page – January 2006

PASTOR’S PAGE – JANUARY 2006 I’m not big on resolutions around the New Year. It seems that if I know that I should do something for my health, or something positive in my life (like simplifying or discarding things that are no longer used) I don’t need to wait until the beginning of a new year. I can start those things anytime. Also, it has always seemed that so many of those well intentioned resolutions made on January 1 have gone by the wayside around January 4 th , so why bother. But there are some resolutions that I think we would do well to include in our lives. Not all of them, for they are a tall order when taken all together. But, perhaps you might start with one. And then, when it has become a planned part of your life you can move on to another. I want to warn you, don’t expect immediate results on any of these. They need multitudes resolving to be involved to become reality. But, work diligently on the one that you pick, see if you can find reports of things improving in your particular area, and be proud that during the coming year you are part of the solution to something. Resolve to do something about the health care mess in our nation, so that we aren’t last among nations in the first world in the health care that we provide for our children, adults and seniors. Resolve to do something to start fixing the infrastructure of our country, so that roads are repaired and levees strengthened and parklands are protected. -

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo Da Vinci) Tom Has Been Seen in A

CAST BIOS TOM RILEY (Leonardo da Vinci) Tom has been seen in a variety of TV roles, recently portraying Dr. Laurence Shepherd opposite James Nesbitt and Sarah Parish in ITV1’s critically acclaimed six-part medical drama series “Monroe.” Tom has completed filming the highly anticipated second season which premiered autumn 2012. In 2010, Tom played the role of Gavin Sorensen in the ITV thriller “Bouquet of Barbed Wire,” and was also cast in the role of Mr. Wickham in the ITV four-part series “Lost in Austen,” alongside Hugh Bonneville and Gemma Arterton. Other television appearances include his roles in Agatha Christie’s “Poirot: Appointment with Death” as Raymond Boynton, as Philip Horton in “Inspector Lewis: And the Moonbeams Kiss the Sea” and as Dr. James Walton in an episode of the BBC series “Casualty 1906,” a role that he later reprised in “Casualty 1907.” Among his film credits, Tom played the leading roles of Freddie Butler in the Irish film Happy Ever Afters, and the role of Joe Clarke in Stephen Surjik’s British Comedy, I Want Candy. Tom has also been seen as Romeo in St Trinian’s 2: The Legend of Fritton’s Gold alongside Colin Firth and Rupert Everett and as the lead role in Santiago Amigorena’s A Few Days in September. Tom’s significant theater experiences originate from numerous productions at the Royal Court Theatre, including “Paradise Regained,” “The Vertical Hour,” “Posh,” “Censorship,” “Victory,” “The Entertainer” and “The Woman Before.” Tom has also appeared on stage in the Donmar Warehouse theatre’s production of “A House Not Meant to Stand” and in the Riverside Studios’ 2010 production of “Hurts Given and Received” by Howard Barker, for which Tom received outstanding reviews and a nomination for best performance in the new Off West End Theatre Awards. -

Fake Realities: Assassination and Race in Popular Culture Kevin Marinella

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects College of Graduate Studies 2018 Fake Realities: Assassination and Race in Popular Culture Kevin Marinella Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses Part of the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Marinella, Kevin. (2018). Fake Realities: Assassination and Race in Popular Culture. In BSU Master’s Theses and Projects. Item 56. Available at http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses/56 Copyright © 2018 Kevin Marinella This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Running Head: FAKE REALITIES: ASSASSINATION AND RACE IN POPULAR CULTURE 1 Fake realities: Assassination and race in popular culture A Thesis Presented by KEVIN MARINELLA Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies Bridgewater State University Bridgewater, Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Criminal Justice MAY 2018 Fake realities: Assassination and race in popular culture 2 Fake realities: Assassination and race in popular culture A Thesis Presented by KEVIN MARINELLA MAY 2018 Approved as to style and content by: Signature:______________________________________________________________ Dr. Wendy Wright, Chair Date: Signature:______________________________________________________________ Dr. Carolyn Petrosino, Member Date: Signature:______________________________________________________________ Dr. Jamie Huff, Member Date: Fake realities: Assassination and race in popular culture 3 ABSTRACT Since the September 11th, 2011 terrorist attacks the United States had been involved in conflicts across the globe. These conflict have given rise to the use of target killing, commonly known as assassination as a way to eliminate enemies of the United States. A majority of those killed are of Middle-Eastern descent and/or are followers of Islam. -

Call for Contributions Fan Phenomena: Game of Thrones with Five Books

Call for Contributions Fan Phenomena: Game of Thrones With five books and approximately eight million words published thus far in the Song of Ice and Fire series (1996-ongoing) and the sixth season of HBO's Game of Thrones currently airing, we are seeing the beginnings of a school of criticism devoted to George R.R. Martin’s works and their peculiar brand of deconstructive and in many ways postmodern interpretations of the fantasy genre and medievalism. Often positioned as the grittier antithesis of J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-Earth, Martin's narrative focuses on the darker side of chivalry and heroism, stripping away these higher ideals to reveal the greed, amorality, and lust for power underpinning them. The Fan Phenomena series from Intellect Press is seeking contributors for a new volume on Game of Thrones. This series explores and decodes the fascination we have with what constitutes an iconic or cult phenomenon and how a particular person, TV show, or film character/film infiltrates its way into the public consciousness. Game of Thrones has done precisely that, first subtly and on the fringes as the book series A Song of Ice and Fire, before the lush production values and dynamic cast of the HBO series made it a worldwide blockbuster. Some suggested topics are listed below, although feel free to propose something not on this list. The only requirement is that your proposed chapter focus not just on the show or the books, but on fans and fan responses to either or both. • Demographics of Game of Thrones fans o Who makes up the Game of Thrones fandom? How does the actual fandom differ from the show's perceived/intended audience? • Location tourism o Fans who visit filming locations for the HBO series in Ireland, Croatia, Spain, etc; how these locations are capitalising on Game of Thrones fans • The cast of the HBO series and their engagement with fans/social media o e.g. -

The Magical Neoliberalism of Network Films

International Journal of Communication 8 (2014), 2680–2704 1932–8036/20140005 The Magical Neoliberalism of Network Films AMANDA CIAFONE1 The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA Transnational network narrative films attempt a cognitive mapping of global systems through a narrative form interconnecting disparate or seemingly unrelated characters, plotlines, and geographies. These films demonstrate networks on three levels: a network narrative form, themes of networked social relations, and networked industrial production. While they emphasize realism in their aesthetics, these films rely on risk and randomness to map a fantastic network of interrelations, resulting in the magical meeting of multiple and divergent characters and storylines, spectacularizing the reality of social relations, and giving a negative valence to human connection. Over the last 20 years, the network narrative has become a prominent means of representing and containing social relations under neoliberalism. Keywords: globalization, neoliberalism, network theory, network narrative films, political economy, international film markets After seeing Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Amores Perros (2000) and Rodrigo García’s Things You Can Tell Just by Looking at Her (2000), Chilean writer Alberto Fuguet confirmed his excitement about being part of the new Latin American cultural boom he called “McOndo.” McOndo, he wrote, had achieved the global recognition of Latin America’s earlier boom time, “magical realism,” as represented in Macondo, the fictional town of Gabriel García Marquez’s Cien Años de Soledad. But now the “flying abuelitas and the obsessively constructed genealogies” (Fuguet, 2001, p. 71) (and the politics) had been replaced with the globalized, popular commercial world of McDonalds: Macondo was now McOndo. -

Alexander Siddig

ALEXANDER SIDDIG Film: Submergence Dr Shadid Wim Wenders Backup Films City of Tiny Lights Al-Dabaran Pete Travis BBC Films Recon Omar Adam Davidson Warner Brothers The Fifth Estate Dr Tarek Haliseh Bill Condon DreamWorks Inescapable Adib Ruba Nadda Killer Films 4.3.2.1 Mr Jauo-pinto Noel Clark Unstoppable Entertainment Clash Of The Titans Hermes Louis Leterrier Warner Bros Miral Jamal Julian Schnabel Pathe Cairo Time Tareq Khalifa Ruba Nadda Foundry Films Spy(ies) Tariq Nicolas Saada France 2 Cinema Doomsday Hatcher Neil Marshall Focus Features Un Homme Perdi Wahid Saleh Danielle Arbid M K 2 Prods. The Nativity Story The Angel Gabriel Catherine Hardwicke New Line Cinema The Last Legion Theodorus Andronikos Doug Lefler Last Legion Prod Syriana Prince Nasir Al- Subaii Stephen Gagan Warner Bros Kingdom Of Heaven Imad Ridley Scott 20th Century Fox Reign Of Fire Ajay Rob Bowman Reign Of Fire Prods. Last First Kiss Lord Sebastian Andy Tennant Columbia Pics World's Greatest Dad Nisse Maria Essen Omega Film Heartbeat Patrick Martin Lima De Faria Stop Film Vertical Limit Karim Martin Campbell Columbia A Dangerous Man Faisal Chris Menaul Enigma Television: The Spy Sudaini Gideon Raff Netflix Gotham Ra's Al Ghul Various Fox The Kennedys After Camelot Onassis Jon Cassar Asylum Entertainment Peaky Blinders Ruben Oliver Various Caryn Mandabach Productions Game Of Thrones Doran Martell Various H B O Tut Amun David Von Ancken Pharaoh Productions Inc. Atlantis King Various Little Monster Films Ltd Da Vinci's Demons Saslan Al Rahim Various Tonto Films -

Game of Thrones Season Six Trading Cards Checklist

Game of Thrones Season Six Trading Cards Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 001 The Red Woman [ ] 002 The Red Woman [ ] 003 The Red Woman [ ] 004 Home [ ] 005 Home [ ] 006 Home [ ] 007 Oathbreaker [ ] 008 Oathbreaker [ ] 009 Oathbreaker [ ] 010 Book of the Stranger [ ] 011 Book of the Stranger [ ] 012 Book of the Stranger [ ] 013 The Door [ ] 014 The Door [ ] 015 The Door [ ] 016 Blood of My Blood [ ] 017 Blood of My Blood [ ] 018 Blood of My Blood [ ] 019 The Broken Man [ ] 020 The Broken Man [ ] 021 The Broken Man [ ] 022 No One [ ] 023 No One [ ] 024 No One [ ] 025 Battle of the Bastards [ ] 026 Battle of the Bastards [ ] 027 Battle of the Bastards [ ] 028 The Winds of Winter [ ] 029 The Winds of Winter [ ] 030 The Winds of Winter [ ] 031 Tyrion Lannister [ ] 032 Ser Jaime Lannister [ ] 033 Cersei Lannister [ ] 034 Daenerys Targaryen [ ] 035 Jon Snow [ ] 036 Petyr "Littlefinger" Baelish [ ] 037 Queen Margaery [ ] 038 Ser Davos Seaworth [ ] 039 Melisandre [ ] 040 Ellaria Sand [ ] 041 Sansa Stark [ ] 042 Sandor Clegane "The Hound" [ ] 043 Missandei [ ] 044 Arya Stark [ ] 045 Lord Varys [ ] 046 Theon Greyjoy [ ] 047 Samwell Tarly [ ] 048 King Tommen Baratheon [ ] 049 Brienne of Tarth [ ] 050 Bronn [ ] 051 Bran Stark [ ] 052 Tormund Giantsbane [ ] 053 Daario Naharis [ ] 054 Roose Bolton [ ] 055 Gilly [ ] 056 High Sparrow [ ] 057 Ramsay Bolton [ ] 058 Jaqen H'ghar [ ] 059 Ser Jorah Mormont [ ] 060 Grey Worm [ ] 061 Waif [ ] 062 Ser Gregor Clegane [ ] 063 Yara Greyjoy [ ] 064 Lady Olenna Tyrell [ ] 065 Eddison Tollett [ ] 066 Podrick Payne -

European Journal of American Studies, 15-3 | 2020 the Reluctant Islamophobes: Multimedia Dissensus in the Hollywood Premodern 2

European journal of American studies 15-3 | 2020 Special Issue: Media Agoras: Islamophobia and Inter/ Multimedial Dissensus The Reluctant Islamophobes: Multimedia Dissensus in the Hollywood Premodern Elena Furlanetto Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/16256 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.16256 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Elena Furlanetto, “The Reluctant Islamophobes: Multimedia Dissensus in the Hollywood Premodern”, European journal of American studies [Online], 15-3 | 2020, Online since 29 September 2020, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/16256 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas. 16256 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License The Reluctant Islamophobes: Multimedia Dissensus in the Hollywood Premodern 1 The Reluctant Islamophobes: Multimedia Dissensus in the Hollywood Premodern Elena Furlanetto 1. Introduction 1 In February 2020,1 Bong Joon-ho’s film Parasite made history winning four Academy Awards, including best foreign picture and best picture, awarded for the first time to a non-Anglophone film. After Parasite’s game-changing success, the question of Orientalism in Hollywood has become more layered; perhaps, as Mubarak Altwaiji suggests, working toward the exclusion of countries from the map of the Orient and their inclusion in the imaginary perimeter of Western progress (see 313).2 Yet, as South Korean cinema makes its grand entrance into the persistently white halls of the Academy, Muslim countries remain underrepresented and Muslim characters continue to be heavily stereotyped. Altwaiji goes as far as suggesting that neo-Orientalism of the post 9/11 kind has triggered a re-evaluation of the classic Orient with the “Arab world” and its stereotyping as its center (314). -

Major Kira of Star Trek: Ds9: Woman of the Future, Creation of the 90S

MAJOR KIRA OF STAR TREK: DS9: WOMAN OF THE FUTURE, CREATION OF THE 90S Judith Clemens-Smucker A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2020 Committee: Becca Cragin, Advisor Jeffrey Brown Kristen Rudisill © 2020 Judith Clemens-Smucker All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Becca Cragin, Advisor The 1990s were a time of resistance and change for women in the Western world. During this time popular culture offered consumers a few women of strength and power, including Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s Major Kira Nerys, a character encompassing a complex personality of non-traditional feminine identities. As the first continuing character in the Star Trek franchise to serve as a female second-in-command, Major Kira spoke to women of the 90s through her anger, passion, independence, and willingness to show compassion and love when merited. In this thesis I look at the building blocks of Major Kira to discover how it was possible to create a character in whom viewers could see the future as well as the current and relatable decade of the 90s. By laying out feminisms which surround 90s television and using original interviews with Nana Visitor, who played Major Kira, and Marvin Rush, the Director of Photography on DS9, I examine the creation of Major Kira from her conception to her realization. I finish by using historical and cognitive poetics to analyze both the pilot episode “Emissary” and the season one episode “Duet,” which introduce Major Kira and display character growth.