Election Law on the Ground: Challenges in Missouri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fact Sheet: Designation of Election Infrastructure As Critical Infrastructure

Fact Sheet: Designation of Election Infrastructure as Critical Infrastructure Consistent with Presidential Policy Directive (PPD) 21, the Secretary of Homeland Security has established Election Infrastructure as a critical infrastructure subsector within the Government Facilities Sector. Election infrastructure includes a diverse set of assets, systems, and networks critical to the administration of the election process. When we use the term “election infrastrucure,” we mean the key parts of the assets, systems, and networks most critical to the security and resilience of the election process, both physical locations and information and communication technology. Specficially, we mean at least the information, capabilities, physical assets, and technologies which enable the registration and validation of voters; the casting, transmission, tabulation, and reporting of votes; and the certification, auditing, and verification of elections. Components of election infrastructure include, but are not limited to: • Physical locations: o Storage facilities, which may be located on public or private property that may be used to store election and voting system infrastructure before Election Day. o Polling places (including early voting locations), which may be physically located on public or private property, and may face physical and cyber threats to their normal operations on Election Day. o Centralized vote tabulation locations, which are used by some states and localities to process absentee and Election Day voting materials. • Information -

Notice of Election

NOTICE OF ELECTION Notice is hereby given that a General Election will be held in the State of Missouri on the 8th day of November, 2016 for the purpose of voting on candidates and statewide ballot measures (Section 115.125, RSMo). DEMOCRATIC PARTY REPUBLICAN PARTY LIBERTARIAN PARTY CONSTITUTION PARTY GREEN PARTY FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT (VOTE FOR 1) HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON TIMOTHY MICHAEL KAINE DEMOCRATIC PARTY DONALD J. TRUMP MICHAEL R. PENCE REPUBLICAN PARTY GARY JOHNSON BILL WELD LIBERTARIAN PARTY DARRELL L. CASTLE SCOTT N. BRADLEY CONSTITUTION PARTY JILL STEIN AJAMU BARAKA GREEN PARTY FOR UNITED STATES SENATOR (VOTE FOR 1) JASON KANDER DEMOCRATIC PARTY ROY BLUNT REPUBLICAN PARTY JONATHAN DINE LIBERTARIAN PARTY FRED RYMAN CONSTITUTION PARTY JOHNATHAN MCFARLAND GREEN PARTY FOR GOVERNOR (VOTE FOR 1) CHRIS KOSTER DEMOCRATIC PARTY ERIC GREITENS REPUBLICAN PARTY CISSE W SPRAGINS LIBERTARIAN PARTY DON FITZ GREEN PARTY LESTER BENTON (LES) TURILLI, JR. INDEPENDENT FOR LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR (VOTE FOR 1) RUSS CARNAHAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY MIKE PARSON REPUBLICAN PARTY STEVEN R. HEDRICK LIBERTARIAN PARTY JENNIFER LEACH GREEN PARTY FOR SECRETARY OF STATE (VOTE FOR 1) ROBIN SMITH DEMOCRATIC PARTY JOHN (JAY) ASHCROFT REPUBLICAN PARTY CHRIS MORRILL LIBERTARIAN PARTY FOR STATE TREASURER (VOTE FOR 1) JUDY BAKER DEMOCRATIC PARTY ERIC SCHMITT REPUBLICAN PARTY SEAN O’TOOLE LIBERTARIAN PARTY CAROL HEXEM GREEN PARTY FOR ATTORNEY GENERAL (VOTE FOR 1) TERESA HENSLEY DEMOCRATIC PARTY JOSH HAWLEY REPUBLICAN PARTY FOR UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE DISTRICT 4 -

Sample Ple Sample Sam Ample Sample Sam

SAMPLE SAMPLE SAMPLE SAMPLE SAMPLE SAMPLE SAMPLE SAMPLE SA SAMPLE SAMPLE SA SAMPLE SAMPLE SA MPL SAMPLE SAMPLE SA MPL DEM SAMPLEREP SAMPLE MPLE SA E in the County ofSAMPLE Cass SAMPLE MPLE Vote for ONE SA FOR ATTORNEY GENERAL MPLE SAMPLE DEM SAMPLE SA TERESA HENSLEY REP JOSH HAWLEY SAMPLELIB MPLE DISTRICT 4 SA Write-in OFFICIAL SAMPLE BALLOT DEM Vote for ONE eneral Election will be held REP SAMPLE MPLE SAM CASS COUNTY, MISSOURI FOR UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE SA LIB LIBERTARIAN - (LIB); CONSTITUTION - (CST); GREEN - (GRN); INDEPENDENT - (IND) NOTICE OF ELECTION GRN GORDON CHRISTENSEN REP MPLE SAMPLE GENERAL ELECTION - NOVEMBER 8, 2016 SAMPLE LIB IND VICKY HARTZLER SA FOR GOVERNORVote for ONE MARK BLISS IND MPLE SAMPLE SAMPLEWrite-in DISTRICT 31 FOR STATEVote SENATOR for ONE SA CHRIS KOSTER DEM MPLE SAMPLE ERIC GREITENS SAMPLEREP SA LIB CISSE W SPRAGINS ED EMERY DEM DON FITZ SAMPLEGRN LORA YOUNG SA MPLREP E SAMPLE LESTER BENTON (LES) TURILLI, JR. TIM WELLS DEMOCRATIC - (DEM); REPUBLICAN - (REP); Vote for ONE DEM Write-in Write-in DISTRICT 33 SAMPLE Vote for ONE MPLE SAMPLE Notice is hereby given that the November G FOR LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR SA FOR STATE REPRESENTATIVE REP DEM on Tuesday, November 8, 2016 as certified to this office by the participating entitiesSAMPLERUSS of CARNAHAN Cass County. REP MPLE SAM LIB MIKE PARSON SALIB CHASE LINDER The ballot for the election shall be in substantially the following form: STEVEN R. HEDRICK DONNA PFAUTSCH A vote for candidates forVote President for ONE PAIR and MPLE CST JENNIFER LEACH SAMPLE Vice President is a vote for their Electors. -

2021 Bicentennial Inauguration of Michael L. Parson 57Th Governor of the State of Missouri

Missouri Governor — Michael L. Parson Office of Communications 2021 Bicentennial Inauguration of Michael L. Parson 57th Governor of the State of Missouri On Monday, January 11, 2021, Governor Michael L. Parson will be sworn in as the 57th Governor of the State of Missouri at the 2021 Bicentennial Inauguration. Governor Michael L. Parson Governor Parson is a veteran who served six years in the United States Army. He served more than 22 years in law enforcement, including 12 years as the sheriff of Polk County. He also served in the Missouri House of Representatives from 2005-2011, in the Missouri Senate from 2011-2017, and as Lieutenant Governor from 2017-2018. Governor Parson and First Lady Teresa live in Bolivar. Together they have two children and six grandchildren. Governor Parson was raised on a farm in Hickory County and graduated from Wheatland High School in Wheatland, Missouri. He is a small business owner and a third generation farmer who currently owns and operates a cow and calf operation. Governor Parson has a passion for sports, agriculture, Christ, and people. Health and Safety Protocols State and local health officials have been consulted for guidance to protect attendees, participants, and staff on safely hosting this year’s inaugural celebration. All inauguration guests will go through a health and security screening prior to entry. Inaugural events will be socially distanced, masks will be available and encouraged, and hand sanitizer will be provided. Guests were highly encouraged to RSVP in advance of the event in order to ensure that seating can be modified to support social distancing standards. -

Daily Congressional Record Corrections for 2019

Daily Congressional Record Corrections for 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 00:56 May 29, 2019 Jkt 089060 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8392 Sfmt 8392 J:\CRONLINE\2019-BATCH-JAN\2019 TITLE PAGES FOR CRI INDEX\2019JANFEB.IDX 2 abonner on DSKBCJ7HB2PROD with CONG-REC-ONLINE VerDate Sep 11 2014 00:56 May 29, 2019 Jkt 089060 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8392 Sfmt 8392 J:\CRONLINE\2019-BATCH-JAN\2019 TITLE PAGES FOR CRI INDEX\2019JANFEB.IDX 2 abonner on DSKBCJ7HB2PROD with CONG-REC-ONLINE Daily Congressional Record Corrections Note: Corrections to the Daily Congressional Record are identified online. (Corrections January 2, 2019 through February 28, 2019) Senate On page S8053, January 2, 2019, first column, The online Record has been corrected to read: the following appears: The PRESIDING OFFI- The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without objection, it CER. Without objection, it is so ordered. The is so ordered. The question is, Will the Senate ad- nominations considered and confirmed are as fol- vise and consent to the nominations of Robert S. lows: Robert S. Brewer, Jr., of California, to be Brewer, Jr., of California, to be United States At- United States Attorney for the Southern District of torney for the Southern District of California for California for the term of four years. Nicholas A. the term of four years; Nicholas A. Trutanich, of Trutanich, of Nevada, to be United States Attor- Nevada, to be United States Attorney for the Dis- ney for the District of Nevada for the term of four trict of Nevada for the term of four years; Brian years. -

Bethany Republican-Clipper the Official Newspaper of Harrison County, Missouri Since 1873 Bethany, Missouri 64424 Vol

Bethany Republican-Clipper The official newspaper of Harrison County, Missouri since 1873 Bethany, Missouri 64424 Vol. 89, No. 18 www.bethanyclipper.com June 6, 2018 75 Cents Towns attempting to meet EPA standards on wastewater output Two Harrison County towns allow the city to retrofit its has been working with several munity also has a three-stage are working on wastewater present lagoon system to com- area communities in developing lagoon facility that needs to be treatment projects to meet new ply with DNR standards. This new treatment systems. brought into compliance with EPA limits on ammonia and ni- would benefit farmers by pro- “We have to figure out what EPA regulations. trogen levels in treated sewage. viding nutrients for their pasture is needed and the corrective Gilman City began advertis- The Ridgeway City Council and row crops and even to have actions that should be taken,” ing for bids this week on their met recently with a representa- access to the water discharged Rains said. treatment facility. The bids will tive of Allstate Consultants En- from the third lagoon. “Some 73 villages and cit- be opened at 1 p.m. on July 9 at gineering of Marceline, Mo., to Sayre offered to come back ies now have issues because the City Clerk’s office. discuss proposed modifications at an evening meeting to hold EPA told DNR that they need to Gilman City’s project will be in the community’s sewage la- discussions with farmers and tighten up their regulations on funded by $500,000 in commu- goon system. -

Secretaries of State Are Crucial for Protecting African American Voters

GETTY IMAGES/IRA L. BLACK GETTY L. IMAGES/IRA Secretaries of State Are Crucial for Protecting African American Voters By Michael Sozan and Christopher Guerrero August 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESSACTION.ORG Contents 1 Introduction and summary 2 Background for the analysis 6 Analyzing the state of elections 11 Recommendations for secretaries of state during the COVID-19 pandemic 14 Conclusion 14 About the authors 14 Acknowledgments 15 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is simultaneously confronting three wrenching challenges: the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, deep economic upheaval, and systemic racism—issues that disproportionately affect African Americans. Compounding these critical issues is the racial discrimination that pervades the U.S. voting system and silences the voices of the communities that are most affected. In several primary elections across the country, there has been a breakdown in election processes—including closed polling places, mail ballot voting hurdles, and malfunctioning voting equipment—causing outsize harm to African American communities. It is important for elected officials to ensure that every American can fully exercise their constitutional right to vote, especially during a pivotal election year. Secretaries of state, although perhaps not the most well-known public officials, serve as the gatekeepers of free and fair elections across the United States. As the top election administrators in most states, they face unprecedented hurdles to running safe elections during a pandemic, on top of their responsibility to ensure that elec- tions are inclusive and accessible. The decisions that secretaries of state make can help determine whether every eligible American can vote and play a meaningful role in transforming the United States into a more just society. -

November 2020 Candidates

Certification of Candidates and Party Emblems Certified by John R. Ashcroft Secretary of State IMPORTANT These are candidates for the General Election on Tuesday, November 3, 2020 JOHN R. ASHCROFT SECRETARY OF STATE JAMES C. KIRKPATRICK STATE OF MISSOURI ELECTIONS DIVISION STATE INFORMATION CENTER (573) 751-2301 (573) 751-4936 August 25, 2020 Dear Election Authority: I, John R. Ashcroft, Secretary of State of the State of Missouri, in compliance with Section 115.401, RSMo, hereby certify that the persons named hereinafter and whose addresses are set opposite their respective names were duly and lawfully nominated as candidates of the above-named parties and independent candidates for the offices herein named to be filled at the General Election to be held November 3, 2020. This 2020 General Election Certification booklet contains: 1. The list of names and addresses of candidates entitled to be voted for at the November 3, 2020 general election; 2. The list of names and addresses of the nonpartisan judicial candidates to be voted for at the November 2020 general election; and 3. The party emblems. These emblems are required by law to be certified by the Secretary of State but are not required to be included on the ballot. Please be advised that candidate filing remains open for certain offices. These offices are denoted with an * in the certification book. Our office will issue supplemental certifications as necessary, should candidates file for those offices. If you are impact- ed by an open filing period, you should consider withholding printing ballots until further notified. If you have any questions, please call us at (800) 669-8683 or (573) 751-2301. -

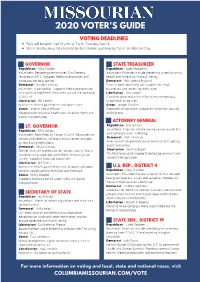

2020 Voter's Guide

2020 VOTER'S GUIDE VOTING DEADLINES Polls will be open from 6 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 3. Mail-in ballots must be received by the election authority by 7 p.m. on Election Day. GOVERNOR STATE TREASUREER Republican - Mike Parson. Republican - Scott Fitzpatrick. Incumbent. Became governor when Eric Greitens Incumbent. Priorities include preserving state's financial resigned in 2018. Opposes Medicaid expansion and health and increasing financial literacy. advocates for local control. Democrat - Vicki Lorenz Englund. Democrat - Nicole Galloway. Plans to boost economy with support for small Incumbent state auditor. Supports Medicaid expansion businesses and access to health care. and wants to implement measures to curb the spread of Libertarian - Nick Kasoff. COVID-19. If elected, plans make the office as environmentally Libertarian - Rik Combs. responsible as possible. Believes in limited government and lower taxes. Green - Joseph Civettini. Green - Jerome Howard Bauer. Opponent of capitalism; proponent of gender equality Advocates for universal health care, disability rights and and diversity. public transportation. ATTORNEY GENERAL LT. GOVERNOR Republican - Eric Schmitt. Republican - Mike Kehoe. Incumbent. Priorities include testing sexual assault kits Incumbent. Appointed by Parson in 2018. Advocates for and fighting human trafficking. seniors and veterans; will expand businesses and jobs Democrat - Rich Finneran. by decreasing regulations. Priorities include prosecution of criminals and fighting Democrat - Alissia Canady. public corruption. Former assistant prosecutor for Jackson County. Wants Libertarian - Kevin Babcock. to create living-wage jobs and reform criminal justice The libertarian party supports limited government and system. Supports Medicaid expansion. laissez-faire capitalism. Libertarian - Bill Slantz. Believes in limited government and advocates for open U.S. -

TABLE 4.15 the Secretaries of State, 2018

SECRETARIES OF STATE TABLE 4.15 The Secretaries of State, 2018 Maximum consecutive State or other Method of Length of regular Date of first Present term Number of terms allowed by jurisdiction Name and party Selection term in years service ends previous terms constitution Alabama John Merrill (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Alaska --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (a) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Arizona Michele Reagan (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Arkansas Mark Martin (R) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 2 California Alex Padilla (D) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Colorado Wayne Williams (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … 2 Connecticut Denise Merrill (D) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 … Delaware Jeffrey Bullock (D) A (b) 4 1/2009 … … … Florida Kenneth Detzner (R) A 4 2/2012 … 1 2 Georgia Brian Kemp (R) E 4 1/2010 1/2019 1 … Hawaii --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (a) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Idaho Lawerence Denney (R) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … … Illinois Jesse White (D) E 4 1/1999 1/2019 4 … Indiana Connie Lawson (R) E 4 3/2012 1/2019 1 2 Iowa Paul Pate (R) E 4 12/2014 12/2018 … … Kansas Kris Kobach (R) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 … Kentucky Alison Lundergan Grimes (D) E 4 12/2011 12/2019 1 2 Louisiana Kyle Ardoin (R) (acting) E 4 5/2018 (c) 1/2020 … … Maine Matt Dunlap (D) L 2 1/2005 (d) 1/2019 (d) 5 (e) Maryland John Wobensmith (R) A … 1/2015 … … … Massachusetts William Francis Galvin (D) E 4 1/1995 1/2019 5 … Michigan Ruth Johnson (R) E 4 1/2011 1/2019 1 2 Minnesota Steve Simon (DFL) E 4 1/2015 1/2019 … … Mississippi C. -

Notice of Election

SAMPLE BALLOT PRIMARY ELECTION AUGUST 4, 2020 COLE COUNTY, MISSOURI NOTICE OF ELECTION Notice is hereby given that the Primary Election will be held in the County of Cole on Tuesday, August 4, 2020 as certified to this office by the participating entities of Cole County. The ballot for the Election shall be in substantially the following form. REPUBLICAN PARTY FOR STATE REPRESENTATIVE FOR ASSESSOR DISTRICT 60 Vote For One FOR GOVERNOR Vote For One JONATHAN ROY MEYERS Vote For One DAVE GRIFFITH RICK PRATHER RALEIGH RITTER CHRISTOPHER "CHRIS" ESTES FOR STATE REPRESENTATIVE MIKE PARSON DISTRICT 62 ALEX MELLER JAMES W. (JIM) NEELY Vote For One FOR TREASURER SAUNDRA McDOWELL CHRIS BEYER Vote For One FOR LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR BRUCE SASSMANN ERIC PETERS Vote For One TOM REED FOR PUBLIC ADMINISTRATOR ARNIE C. AC DIENOFF Vote For One FOR CIRCUIT JUDGE MIKE KEHOE CIRCUIT 19 DIVISION 2 RALPH JOBE AARON T WISDOM Vote For One DEMOCRATIC PARTY MIKE CARTER DAVID G. BANDRÉ FOR SECRETARY OF STATE DANIEL GREEN FOR GOVERNOR Vote For One FOR CIRCUIT JUDGE Vote For One JOHN R. (JAY) ASHCROFT CIRCUIT 19 DIVISION 3 NICOLE GALLOWAY FOR STATE TREASURER Vote For One Vote For One COTTON WALKER JIMMIE MATTHEWS SCOTT FITZPATRICK MARK RICHARDSON FOR ATTORNEY GENERAL ANTOIN JOHNSON Vote For One FOR ASSOCIATE CIRCUIT JUDGE DIVISION 5 ERIC SCHMITT ERIC MORRISON Vote For One FOR UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE BRIAN K. STUMPE ROBIN JOHN DANIEL DISTRICT 3 TODD T. SMITH VAN QUAETHEM Vote For One MATT WILLIS FOR LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR BRANDON WILKINSON TIM ANDERSON Vote For One -

Kathy Boockvar - Wikiwand

11/8/2020 Kathy Boockvar - Wikiwand Kathy Boockvar Secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Incumbent Assumed office January 5, 2019 Acting: January 5, 2019 – November 19, 2019 Governor Tom Wolf Preceded by Robert Torres (acting) Personal details Kathryn Boockvar Born October 23, 1968 (age 52) New York City, New York, U.S. Political party Democratic Spouse(s) Jordan Yeager University of Pennsylvania (BA) Education American University (JD) https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Kathy_Boockvar 2/9 11/8/2020 Kathy Boockvar - Wikiwand Kathryn "Kathy" Boockvar (born October 23, 1968)[1] is an American attorney and politician who serves as the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania since January 5, 2019, appointed to the position by Governor Tom Wolf. She has previously served as Senior Advisor to the Governor on Election Modernization, beginning in March 2018.[2] In August 2019, she was named co-chair of the Elections Committee of the National Association of Secretaries of State.[3] Boockvar previously served as Chief Counsel at the Department of Auditor General, on the Board of Commissioners of the Delaware River Port Authority, and as Executive Director of Lifecycle WomanCare, a birth center in suburban Philadelphia.[4] She has worked as a poll worker and voting-rights attorney in Pennsylvania.[5] Early life and education Born in Staten Island,[6] Boockvar was raised in Hewlett Neck, New York, where she attended Hewlett High School.[7] Boockvar earned her Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1990 and her Juris Doctor from the Washington College of Law at American University in 1993.[5] Career She is a member of the Bar of the U.S.