Narratives of Famine – Somalia 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Series Livelihood Baseline Analysis Baidoa-Urban

Technical Series Report No VI. 22 May 20, 2009 Livelihood Baseline Analysis Baidoa-Urban Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia Box 1230, Village Market Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 254-20-4000000 Fax: 254-20-4000555 Website: www.fsnau.org Email: [email protected] Technical and Funding Agencies Managerial Support European Commission FSNAU Technical Series Report No VI. 18 ii Issued May 20, 2009 Acknowledgements This assessment would not have been possible without funding from the European Commission (EC) and the US Office of Foreign Disaster and Assistance (OFDA). FSAU would like to extend a special thanks to FEWS NET for their funding contributions and technical support, especially to Alex King, a consultant of the Food Economy Group (FEG) who lead the urban analysis. The study benefited from the contributions made by Mohamed Yusuf Aw-Dahir, the FEWS NET Representative to Somalia, and Sidow Ibrahim Addow, FEWS NET Market and Trade Advisor. FSAU would also like to extend a special thanks to Bay region and Baidoa local government authorities and agencies, the Baidoa Intellectual Association and the various other partner organizations and community members that provided information for the assessment. The fieldwork and analysis of this study would not have been possible without the leading baseline expertise and work of the two FSAU Senior Livelihood Analysts and the FSAU Livelihoods Baseline Team consisting of 7 analysts, who collected and analyzed the field data and who continue to work and deliver high quality outputs under very difficult conditions in Somalia. This team was lead by FSAU Lead Livelihood Baseline Livelihood Analyst, Abdi Hussein Roble, and Assistant Lead Livelihoods Baseline Analyst, Abdulaziz Moalin Aden, and the team of FSAU Field Analysts included, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, Abdirahaman Mohamed Yusuf, Yusuf Warsame Mire, Mohanoud Ibrahim Asser and Abdulbari Abdi sheikh. -

Somali Region

Federalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia. A comparative study of the Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz regions Adegehe, A.K. Citation Adegehe, A. K. (2009, June 11). Federalism and ethnic conflict in Ethiopia. A comparative study of the Somali and Benishangul-Gumuz regions. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13839 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13839 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 8 Inter-regional Conflicts: Somali Region 8.1 Introduction The previous chapter examined intra-regional conflicts within the Benishangul-Gumuz region. This and the next chapter (chapter 9) deal with inter-regional conflicts between the study regions and their neighbours. The federal restructuring carried out by dismantling the old unitary structure of the country led to territorial and boundary disputes. Unlike the older federations created by the union of independent units, which among other things have stable boundaries, creating a federation through federal restructuring leads to controversies and in some cases to violent conflicts. In the Ethiopian case, violent conflicts accompany the process of intra-federal boundary making. Inter-regional boundaries that divide the Somali region from its neighbours (Oromia and Afar) are ill defined and there are violent conflicts along these borders. In some cases, resource conflicts involving Somali, Afar and Oromo clans transformed into more protracted boundary and territorial conflicts. As will be discussed in this chapter, inter-regional boundary making also led to the re-examination of ethnic identity. -

Epidemiological Week 45 (Week Ending 12Th November, 2017)

Early Warning Disease Surveillance and Response Bulletin, Somalia 2017 Epidemiological week 45 (Week ending 12th November, 2017) Highlights Cumulative figures as of week 45 Reports were received from 226 out of 265 reporting 1,363,590 total facilities (85.2%) in week 45, a decrease in the reporting consultations completeness compared to 251 (94.7%) in week 44. 78,596 cumulative cases of Total number of consultations increased from 69091 in week 44 to 71206 in week 45 AWD/cholera in 2017 The highest number of consultations in week 44were for 1,159 cumulative deaths other acute diarrhoeas (2,229 cases), influenza like illness of AWD/Cholera in 2017 (21,00 cases) followed by severe acute respiratory illness 55 districts in 19 regions (834 cases) reported AWD/Cholera AWD cases increased from 77 in week 44 to 170 in week 45 cases No AWD/cholera deaths reported in all districts in the past 7 20794 weeks cumulative cases of The number of measles cases increased from in 323 in week suspected measles cases 44 to 358 in week 45 Disease Week 44 Week 45 Cumulative cases (Wk 1 – 45) Total consultations 69367 71206 1363590 Influenza Like Illness 2287 1801 50517 Other Acute Diarrhoeas 2240 2234 60798 Severe Acute Respiratory Illness 890 911 16581 suspected measles [1] 323 358 20436 Confirmed Malaria 269 289 11581 Acute Watery Diarrhoea [2] 77 170 78596 Bloody diarrhea 73 32 1983 Whooping Cough 56 60 687 Diphtheria 8 11 221 Suspected Meningitis 2 2 225 Acute Jaundice 0 4 166 Neonatal Tetanus 0 2 173 Viral Haemorrhagic Fever 0 0 130 [1] Source of data is CSR, [2] Source of data is Somalia Weekly Epi/POL Updates The number of EWARN sites reporting decrease from 251 in week 44 to 226 in week 45. -

Calula Calula Calula Calula BOSSASO BOSSASO !

Progression of Nutrition Situation (Gu 2011 - Deyr 2015/16) SOMALIA - ESTIMATED NUTRITION SITUATION (IPC PHASES) SOMALIA - ESTIMATED NUTRITION SITUATION (IPC PHASES) SOMALIA - ESTIMATED NUTRITION SITUATION (IPC PHASES) August , 2012 (Based on June/July, 2012 surveys) -IPC Ver 2 December , 2012 (Based on October-December, 2012 surveys) -IPC Ver 2 August 16th , 2011 (Based on June/July surveys) - IPC Ver 2 SOMALIA - ESTIMATED NUTRITION SITUATION (IPC PHASES) SOMALIA - ESTIMATED NUTRITION SITUATION (IPC PHASES) Gu 2011 January , 20Deyr12 (Based on N o2011/12vember/December, 2011 surveys) -IPC Ver 2 Gu 2012 Deyr 2012/13 August , 2013 (BGuased on A2013pril-June, 2013 surveys) -IPC Ver 2 Calula Calula Calula Calula BOSSASO BOSSASO !. !. BOSSASO Calula BOSSASO !. Qandala !. Qandala Qandala Las Qoray/ Qandala Las Qoray/ BOSSASO Zeylac Bossaaso Zeylac Bossaaso Las Qoray/ !. Badhan Las Qoray/ Badhan Zeylac Bossaaso Qandala Lughaye ERIGABO Zeylac Lughaye ERIGABO Badhan !. Badhan Bossaaso !. Lughaye ERIGABO Las Qoray/ AWDAL Lughaye ERIGABO !. Zeylac Bossaaso Iskushuban AWDAL AWDAL Badhan Baki !. Baki Iskushuban Iskushuban Lughaye ERIGABO Berbera AWDAL Baki !. Borama SANAG Iskushuban Borama Berbera SANAG Berbera AWDAL Baki Borama SANAG Iskushuban BORAMA Ceel Afweyne BARI Berbera BORAMA Ceel Afweyne BARI Baki !. Sheikh Borama SANAG Sheikh BORAMA Ceel Afweyne BARI Berbera Ceerigaabo !. Ceerigaabo !. Sheikh Borama SANAG W. GALBEED BORAMA Ceel Afweyne BARI W. GALBEED W. GALBEED Ceerigaabo Gebiley Sheikh Gebiley BORAMA Ceel Afweyne BARI HARGEYSA BURAO -

8.. Colonialism in the Horn of Africa

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The state, the crisis of state institutions and refugee migration in the Horn of Africa : the cases of Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia Degu, W.A. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Degu, W. A. (2002). The state, the crisis of state institutions and refugee migration in the Horn of Africa : the cases of Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia. Thela Thesis. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 8.. COLONIALISM IN THE HORN OF AFRICA 'Perhapss there is no other continent in the world where colonialism showed its face in suchh a cruel and brutal form as it did in Africa. Under colonialism the people of Africa sufferedd immensely. -

Electronic Communication and an Oral Culture: the Dynamics of Somali Websites and Mailing Lists

ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATION AND AN ORAL CULTURE: THE DYNAMICS OF SOMALI WEBSITES AND MAILING LISTS BY ABDISALAM M. ISSA-SALWE A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THAMES VALLEY UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CENTRE FOR INFORMATION MANAGEMENT SCHOOL OF COMPUTING AND TECHNOLOGY THAMES VALLEY UNIVERSITY SUPERVISORS: DR. ANTHONY OLDEN, THAMES VALLEY UNIVERSITY EMERITUS PROFESSOR I M LEWIS, LSE, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON EXAMINERS: PROFESSOR CHRISTINE MCCOURT, THAMES VALLEY UNIVERSITY DR. MARTIN ORWIN, SOAS, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON NOVEMBER 2006 TO MY WIFE HAWO, MY CHILDREN MOHAMED-NASIR, MOHAMUD, ALI, HAFSA-YALAH, HAMDA, SHARMARKE AND YUSUF-HANAD ACKNOWLEDGMENT Foremost, I would like to thank to the Council for Assisting Refugee Academics (CARA) who helped in funding my studies. I would like to thank my thesis advisors, Dr. Tony Olden (Thames Valley University) and Emeritus Professor I M Lewis (London School of Economics) for their continuous encouragement, optimism and confidence in me to make it possible to write this dissertation. Both Dr. Olden and Emeritus Professor Lewis put an enormous amount of time and effort into supervision. Likewise, this study has been enhanced through the incisive comments of Dr Stephen Roberts (Thames Valley University). I also appreciate the advice of Dr Mohamed D. Afrax and Abdullahi Salah Osman who read and commented on the manuscript of this dissertation. I am also thankful to Ahmed Mohamud H Jama (Nero) who allowed me to have useful material relevant to my research; Dr. Ebyan Salah who solicited female correspondents to reply to the research questionnaires. I am also grateful to Said Mohamed Ali (Korsiyagaab) and Ismail Said Aw-Muse (PuntlandState.com) who gave me permission to use their websites statistics. -

Unicef Somalia

NUTRITION SURVEY REPORT BURHAKABA DISTRICT BAY REGION SOMALIA UNICEF SOUTH/CENTRAL ZONE OF SOMALIA BAIDOA OFFICE 2-15 JUNE 2000 Burhakaba District Nutrition Survey, June 2000 1. INTRODUCTION This nutrition survey is the ninth in a series of surveys agreed between UNICEF and FSAU throughout South and Central Somalia. UNICEF planned the surveys, conducted the fieldwork of data collection, trained enumerators, monitored survey activities, carried out data analysis and interpretation and paid the survey cost. UNICEF is grateful to World Vision and Burhakaba Health Authority who facilitated the work in Burhakaba District. 1.2 SURVEY JUSTIFICATION UNICEF supported a supplementary feeding programme in Burhakaba town in the last quarter of 1999 through Burhakaba Health Authority. UNICEF’s supplementary feeding support to Burhakaba was stopped in December 1999 due to misappropriation of supplies. Burhakaba district is situated on the frontline between RRA and SNA factions, is mainly dependent on agriculture and livestock and has suffered continuously from drought, security problems and lack of access to the main markets in Baidoa and Mogadishu during the past five years. Results from the Burhakaba town nutrition survey in September 1999 depicted the highest malnutrition rates in Bay region, with 28% global malnutrition. Although few humanitarian interventions have been possible in Burhakaba district that could improve the level of malnutrition, CARE International managed to continue to deliver food to all the main rural villages in the district, despite insecurity. The decision to conduct another nutrition survey in Burhakaba was made in order not only to compare the results with the previous data, but to obtain baseline data to assist in planning interventions by World Vision, which plans to start working in the district in July 2000. -

Weekly Update on Displacement and Other Population Movements in South-Central Somalia 14 - 20 April 2014 UNHCR Somalia

Weekly update on displacement and other population movements in South-Central Somalia 14 - 20 April 2014 UNHCR Somalia Overview Total estimated IDPs for the week 1,500 In summary, close to 1,500 civilians were displaced during the reporting period. Marka and the outskirts of Mogadishu are now major places of new displacement. IDPs in these Total estimated IDPs since early March 2014 72,700 locations are in need of assistance. ETHIOPIA Ceel Barde Belet Weyne Displacement to Luuq town (Gedo) GALGADUUD According to UNHCR partners, 50 individuals arrived to Luuq from Buurdhuubo (southern Rab dhuure Gedo). The estimated total number of new IDPs in Luuq since the beginning of March is now BAKOOL around 2,450 persons. IDPs from Buurdhuubo are of the same clan as Luuq host Buur dhuxunle Xudur HIRAAN community and are accommodated by extended family members from Luuq. Luuq Waajid Bulo Barde Kurtow Baidoa GEDO Buurdhuubo Buur Hakaba SHABELLE DHEXE Displacement to Baidoa town (Bay) from Bakool region BAY Another 120 IDPs arrived to Baidoa from Bakool region (mainly Wajid district). UNHCR also received reports of the onset of new displacement 150 individuals from Buur dhuxunle BANADIR town in Bakool to the near by villages after SFG attacked the town. Qoryooley Mogadishu SHABELLE HOOSE Marka KENYA JUBA DHEXE Buulo mareer Displacement inside Shabelle Hoose Baraawe Indian Ocean Afmadow Jilib Around 500 civilians arrived to Marka from Qoryooley town over the last couple of days. The total number of new IDPs in Marka is now 9 -9,500 persons. Dobley Region IDP Pop. Legend JUBA HOOSE Bakool 6,990 Main States/Divisions of Origin Kismaayo Banadir 8,350 Bay 16,960 Refugee Camp Displacement to Mogadishu Gedo 3,098 Town, village Hiraan 27,000 Around 400 IDPs from Qoryoley town (Shabelle Hoose) and 250 from Buulo Mareer arrived Major movements to Mogadishu (Km 7-13). -

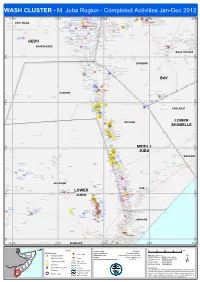

WASH Cluster (2012) ! Sustained Water Airstrip ! ! P ! ! ! Nominal Scale at A3 Paper Size: 1:820,000 All Admin

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

South and Central Somalia Security Situation, Al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups

1/2017 South and Central Somalia Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Report based on interviews in Nairobi, Kenya, 3 to 10 December 2016 Copenhagen, March 2017 Danish Immigration Service Ryesgade 53 2100 Copenhagen Ø Phone: 00 45 35 36 66 00 Web: www.newtodenmark.dk E-mail: [email protected] South and Central Somalia: Security Situation, al-Shabaab Presence, and Target Groups Table of Contents Disclaimer .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and methodology ......................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations..................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Security situation ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. The overall security situation ........................................................................................................ 7 1.2. The extent of al-Shabaab control and presence.......................................................................... 10 1.3. Information on the security situation in selected cities/regions ................................................ 11 2. Possible al-Shabaab targets in areas with AMISOM/SNA presence ....................................................... -

Cholera Epidemiological Week 15 (10 – 16 April 2017)

Situation report for acute watery diarrhoea/ cholera Epidemiological week 15 (10 – 16 April 2017) Cumulative key figures Highlights 10 – 16 April 2017 A total of 2,984 AWD/ cholera cases and 34 deaths (CFR– 1.1%) were reported during week 15 (10 – 16 April 2017) in 50 2,984 new cases in week 15 districts in 13 regions. Of these, 175 cases were reported from Iidale village(in-accessible) district Baidoa in Bay region, which 34 deaths (CFR–1.1%) in week 15 represents 5.9% of the total cases. There is a slight decrease in the number of new AWD/ cholera 51.9 % cases females cases and deaths reported – 2984 cases/ 34 deaths were 33.4% of cases are children under 5 recorded in week 15 compared to 3128 cases/ 32 deaths in years of age week 14. 50 districts reported AWD/ cholera New locations that have reported new AWD/ cholera cases cases and deaths are: Busul Village, Mintane, Saydhalow and Landanbal Village Baidoa district in Bay region, Abudwak Galinsor Village, Addado district Guriel Village, Dusmareb 28,408 cumulative cases since week 1 district in Galgadud region and Bulomarer Village district Kurtunwarey in Lower Shebelle region. Additional alerts were 558 cumulative deaths (CFR–2.0%) recorded from other regions or districts; verification by since week 1 to week 15 surveillance officers is ongoing. Situation update A total of 2984 AWD/ cholera cases and 34 deaths (CFR–1.1%) were reported during week 15 (10- to 16th April 2017) from 50 districts in 13 regions. Of these cases, 175 cases were reported from Iidale village district Baidoa in Bay which represents 5.9% of the total cases; Out of 10 stool samples collected from Bardere district, 6 have tested positive for Vibrio Cholerea. -

Bay Bakool Rural Baseline Analysis Report

Technical Series Report No VI. !" May 20, 2009 Livelihood Baseline Analysis Bay and Bakool Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit - Somalia Box 1230, Village Market Nairobi, Kenya Tel: 254-20-4000000 Fax: 254-20-4000555 Website: www.fsnau.org Email: [email protected] Technical and Funding Agencies Managerial Support European Commission FSNAU Technical Series Report No VI. 19 ii Issued May 20, 2009 Acknowledgements These assessments would not have been possible without funding from the European Commission (EC) and the US Office of Foreign Disaster and Assistance (OFDA). FSNAU would like to also thank FEWS NET for their funding contributions and technical support made by Mohamed Yusuf Aw-Dahir, the FEWS NET Representative to Soma- lia, and Sidow Ibrahim Addow, FEWS NET Market and Trade Advisor. Special thanks are to WFP Wajid Office who provided office facilities and venue for planning and analysis workshops prior to, and after fieldwork. FSNAU would also like to extend special thanks to the local authorities and community leaders at both district and village levels who made these studies possible. Special thanks also to Wajid District Commission who was giving support for this assessment. The fieldwork and analysis would not have been possible without the leading baseline expertise and work of the two FSNAU Senior Livelihood Analysts and the FSNAU Livelihoods Baseline Team consisting of 9 analysts, who collected and analyzed the field data and who continue to work and deliver high quality outputs under very difficult conditions in Somalia. This team was led by FSNAU Lead Livelihood Baseline Livelihood Analyst, Abdi Hussein Roble, and Assistant Lead Livelihoods Baseline Analyst, Abdulaziz Moalin Aden, and the team of FSNAU Field Analysts and Consultants included, Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud, Abdirahaman Mohamed Yusuf, Abdikarim Mohamud Aden, Nur Moalim Ahmed, Yusuf Warsame Mire, Abdulkadir Mohamed Ahmed, Abdulkadir Mo- hamed Egal and Addo Aden Magan.