Crack Manifesto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concept of Generation in the Study of Twenty-First Century Mexican Literature: Usefulness and Limitations

The Concept of Generation in the Study of Twenty-First Century Mexican Literature: Usefulness and Limitations Elsa M. Treviño Investigadora independiente [email protected] Recibido: 15/02/2018 – Aceptado: 05/06/2018 DOI: 10.17533/udea.lyl.n74a06 Abstract: This article analyzes the concept of generation as a methodological tool for con- temporary literary research, advancing its use to characterize aesthetic trends in the artistic production of diverse groups of coetaneous writers. By providing a cultural history of the uses of the category in Mexican literary studies, it examines the applicability and limitations of the concept of generation, highliting the importance of contextual and diachronic aware- ness in its deployment. This study then advocates for an understanding of a generation as a porous sociobiological category that groups several people under a similar Weltanschauung. It contends that the heterogeneity of Mexican cultural nationalism generates an equivocal ground for the literature of the generation of writers born in the 1960s and 1970s, and argues for the consideration of the cluster of Mexican authors born in these decades as a generation. Keywords: Generational analysis, Mexican Literature, Mexican Cultural Studies, Literary Research Methods, Literature of the crack. EL CONCEPTO DE GENERACIÓN EN EL ESTUDIO DE LA LITERATURA MEXICANA DEL SIGLO XXI: USOS Y LIMITACIONES Resumen: Este artículo analiza el concepto de generación como una herramienta metodo- lógica para la investigación literaria contemporánea, proponiendo el uso del concepto para caracterizar las tendencias estéticas en la producción artística de diversos grupos de escri- tores coetáneos. A partir de una historia cultural de los usos de la categoría en los estudios literarios mexicanos, se examinan la aplicabilidad y limitaciones del concepto, recalcando la importancia de la conciencia textual y diacrónica en la aplicación de dicha categoría ana- lítica. -

EL FIN DE LA NARRATIVA LATINOAMERICANA Jorge Volpi

REVISTA DE CRITICA LITERARIA LATINOAMERICANA Año XXX, Nº 59. Lima-Hanover, 1er. Semestre de 2004, pp. 33-42 EL FIN DE LA NARRATIVA LATINOAMERICANA Jorge Volpi Para Carlos Fuentes, por supuesto Como el tema de estas reflexiones es el futuro de la narrativa latinoamericana, me permitiré citar, in extenso, el célebre artículo del profesor Ignatius H. Berry, catedrático de Hispanic and Chica- na Literature de la Universidad Estatal de Dakota del Norte, pu- blicado en la revista Im/positions en el mes de junio de 2055: Cincuenta años de literatura hispánica, 2005-2055: un canon imposible De vez en cuando ocurre que, en un período histórico restringido, de pronto surge un torrente de escritores que trastoca para siempre una tradición literaria. Los ejemplos son muy conocidos: la Atenas de Peri- cles, el Quattrocento italiano, la Inglaterra isabelina, el clasicismo francés y, por supuesto, el Siglo de Oro español. En Hispanoamérica, una región que llegó muy tarde a la modernidad, la época de esplendor de su literatura no se produjo sino hasta la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Por más que los filólogos y eruditos se obstinen en encontrar anteceden- tes notables en épocas anteriores, la realidad es que no existe ninguna obra escrita en esta región del mundo que resulte universalmente rele- vante antes de la aparición de esa pareja de colosos formada por el ar- gentino Jorge Luis Borges y el mexicano Juan Rulfo. Poco después, surgió al fin un grupo compacto de escritores capaz de convertir a Hispanoamérica en un referente obligado de la cultura occi- dental. Conocido con el nombre poco edificante de boom, su núcleo cen- tral estuvo formado por Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, Mario V. -

Swedish House Mafias “Don't You Worry Child” Passerer 1 Millioner Solgte Kopier

21-11-2012 12:56 CET Swedish House Mafias “Don’t You Worry Child” passerer 1 millioner solgte kopier Den svenske stjernegruppen Swedish House Mafia kan i dag annonsere at singelen ”Don’t You Worry Child” har passert 1 millioner solgte kopier verden over på 9 uker. I Norge har singelen i skrivende stund solgt til 3x platina og over 4 millioner streams på Spotify. Denne helgen besøker avskjedsturnéen ”One Last Tour” Stockholm, hvor Swedish House Mafia spiller sine tre siste konserter på svensk jord for mer enn 105 000 fans. Billettene ble utsolgt på få timer. Fredag kveld gjester gruppen TV-programmet ”Skavlan” på NRK1. Swedish House Mafia spiller på Telenor Arena utenfor Oslo lørdag 22 desember, dette blir gruppens siste konsert noensinne i Europa. Se innebygd innhold her Live-video "Don't You Worry Child: Se video på YouTube her EMI er ett av verdens største og eldste plateselskaper. Blant våre internasjonale artister finner du The Beatles, Pink Floyd, David Bowie, Katy Perry, Robyn, Coldplay, David Guetta, Swedish House Mafia, Roxette, Kim Larsen, Tinie Tempah, Adam Tensta, Alice In Chains, LCD Soundsystem, Deadmau5, The Kooks, 30 Seconds To Mars, Jane’s Addiction, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Rise To Remain, Iron Maiden m.fl. Blant våre norske artister finner du, Åge Aleksandersen, Susanne Sundfør, Marit Larsen, Henning Kvitnes, Hellbillies, Frida Amundsen, Lars Haavard Haugen, Madrugada, Dumdum Boys, Morten Abel, Halvdan Sivertsen m.fl Kontaktpersoner Matea Grøvik Pressekontakt Prosjektleder [email protected] + 47 478 65 722 Mona Olsen Pressekontakt Senior Project Manager Domestic [email protected] +47 95 82 54 20 Yordana Jakobsen Pressekontakt International Project Manager [email protected] +47 47 30 64 73. -

Early-Chapters-–-SIMPLY-BRILLIANT.Pdf

01 02 03 PROLOGUE: THE NEW 04 STORY OF SUCCESS 05 06 “The Possible Is Immense” 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 ho doesn’t want to be part of a great success story? 14 To run, start, or play a leadership role in a company 15 that wins big and changes the course of its industry. 16 ToW launch a brand that dazzles customers and dominates its mar- 17 ket. To be the kind of executive or entrepreneur who creates jobs, 18 generates wealth, and builds an organization bursting with energy 19 and creativity. 20 These days, in the popular imagination, the quest for success 21 has become synonymous with the spread of disruptive technolo- 22 gies and viral apps, with the rise of radical business models and 23 newfangled work arrangements. This is the stuff that fuels the 24 dreams of countless engineers and venture capitalists in Silicon 25 Valley, and inspires hard-charging innovators such as Facebook’s 26 Mark Zuckerberg and Uber’s Travis Kalanick. The “new economy,” 27 the story goes, belongs to a new generation of companies and lead- S28 ers who have little in common with what came before. N29 1 9781591847755_Simply_i-xvi_1-256_B1.indd 1 7/27/16 10:56 PM SIMPLY BRILLIANT 01 But why should the story of success be the exclusive domain of 02 a few technology-driven start-ups or a handful of young billion- 03 aires? The story of this book, its message for leaders who aim to do 04 something important and build something great, is both simple 05 and subversive: In a time of wrenching disruptions and exhilarat- 06 ing advances, of unrelenting turmoil and unlimited promise, the 07 future is open to everybody. -

The Radicals and the Renaissance Nationalistic, Class Conscious, and International-Minded Than Were 5· Can-Born Blacks."84

=":S'" ttlt:;J UI;;I;;U lllgllly lj~fieficia1 to Harlem-and to America at Essays focusing on the contributions of Caribbean Americans to Harlem the United States would not have called attention to Huiswoud's and "gifts" to the Third International. Domingo and his colleagues however, the significance of the 1922 Moscow congress in placing the ofall peoples ofAfrican descent on the international agenda. Wayne F. per has noted that "the official stance of the Comintern regarding 1922 was influenced by West Indians, who were simultaneously much The Radicals and the Renaissance nationalistic, class conscious, and international-minded than were 5· can-born blacks."84 When the first version ofDomingo's article was issued in March 1925, ofthe four veteran radicals were positioned to wage their campaign racism and colonialism on many fronts as functionaries of organizati( allied with the Workers Party, such as the ANLe. Hermie was also now tiorred to join the group. She had graduated from high school in 1924 through Huiswoud had become friendly with his close comrades and As Hermie Dumont approached her twentieth birthday in 1925 she was be to radical politics along with the gifts ofwriters and artists in Harlem. ginning to appreciate that she was in the midst of a vibrant, eclectic, creative Huiswoud went to Chicago to help launch the ANLC he asked her to community. Bold print on the cover ofthe March 1925 Survey Graphic mag for him. And she did. azine declared "Harlem-Mecca of the New Negro" and included interest ing short stories and other writings by people she had met or recognized from meetings, newspaper articles, or just walking down the street. -

Tim Minchin with West Australian Symphony Orchestra Apart / Together

WORLD PREMIERE TIM MINCHIN WITH WEST AUSTRALIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA APART / TOGETHER Image: Damian Bennett Perth Festival acknowledges the Noongar people who continue to practise their values, language, beliefs and knowledge on their kwobidak boodjar. They remain the spiritual and cultural birdiyangara of this place and we honour and respect their caretakers and custodians and the vital role Noongar people play for our community and our Festival to flourish. Stay COVID-19 safe 1.5m Physical distancing Wash your hands Stay home if you are sick Register your attendance For latest health advice visit healthywa.wa.gov.au/coronavirus TIM MINCHIN WITH WEST AUSTRALIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA APART / TOGETHER KAARTA KOOMBA / PERTH CBD KINGS PARK & BOTANICAL GARDEN M T W T F S S FEBRUARY 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Sat & Sun Gates open 5.30pm Tim Minchin 7pm Duration 80mins With thanks to Mellen Events and Kings Park & Botanic Garden CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTENTS WELCOME WELCOME 6 Welcome 8 Credits 10 Repertoire CREDITS BACKGROUND 12 Apart Together - The Album REPERTOIRE BIOGRAPHIES 20 Tim Minchin 22 Jessica Gethin BACKGROUND 24 West Australian Symphony Orchestra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 26 Perth Festival Partners BIOGRAPHIES 27 Perth Festival Donors * Just tap the interactive tabs on the left to skip to a specific section ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS WELCOME Image: Jess Wyld CREDITS Perth Festival 2021 is a love song to this place – its people, artists and stories. And so, it is fitting that one of our city’s favourite sons (and a dear friend of many REPERTOIRE of us in the Festival family and beyond) is back in town to perform a special version of his very personal album Apart / Together. -

Brevard Live March 2012

Brevard Live March 2012 - 1 2 - Brevard Live March 2012 Brevard Live March 2012 - 3 4 - Brevard Live March 2012 Brevard Live March 2012 - 5 6 - Brevard Live March 2012 Content march 2012 FEATURES page 51 LES DUDEK CY CURNIN Columns During the 70s and 80s, Les Dudek made The Fixx, lead by Cy Curnin, hit the charts with flashy hits like “One Thing Charles Van Riper waves as one of the hottest guitar players Political Satire on the rock scene. He loaned his talent to Leads to Another,” “Saved By Zero” 20 famous performers like Boz Scaggs and and “Red Skies.” Matt Bretz recently Calendars Steve Miller. With 6 solo albums under talked to Curnin. his belt, he’s now part of rock history. Page 16 23 Live Entertainment, Page 10 Concerts, Festivals THE MOODY BLUES PADDLE BOARDING Chris Long Paddle boarding has just started to come 28 Political Blog Since the 60s, as a part of the histor- into the limelight with its enjoyable ath- ic original British invasion of Super letic characteristics and the rider’s spirited Brevard Scene groups, The Moody Blues have lit up unity with the water. Joe Cronin checked We’re Out There! the hearts and minds of millions of rock it out. 31 fans creating soundtracks of our lives. Page 39 Page 13 Out & About Brevard’s vibrant CHRISTOPHER BREWER 37 club & restaurant GLEN CAMPBELL scene He’s been a legend in country music. He is an artist with a very distinct and recognizable style who has been on a Just recently he announced that he has Life & The Beach Alzheimer’s. -

Eagle 2009 Temp

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 19 - NUMBER 12 FREE The Kohkums are home for Christmas From left Dalton Lightfoot, Mitchell Poundmaker, Cory Dallas Standing and Krystle Pederson bring the Rez Christmas story to a close with a four day run at the Broadway Theatre. (Photo by Sweetmoon Photography) WALKING THE TALK Residential school survivor Eugene Arcand has high praise for the Frances Morrison Central Library in Saskatoon. - Page 3 RAPPING THE ISSUES Beary D’s music is touching some nerves, dealing with some of the tough issues of the day . - Pag e 12 ONE LAST TOUR Curtis Peeteetuce is leaving his role as artistic director of GTNT but he’s enjoying one more fling with the Kohkums. - Page 14 SHE’S A FIGHTER Shana Pasapa is doing her best to help women find the power to look after themselves in tough situations. - Page 21 SHE’S A PRINCESS Popular Christmas show has been around since 2001 Stephanie Bellegarde has been crowned FSIN princess in By John Lagimodiere most successful tour season ever. the pageant’s 70th anniversary Of Eagle Feather News The Christmas Kohkoms were originally created year. - P age 27 SASKATOON – The Kohkums from Kitweenook, by Curtis Peeteetuce in 2001 for the Circle of Voices from the holiday fan favourite Rez Christmas, hit the program. It began a holiday tradition for the company Newsmaker of the Year Edition big time this year. with many of the actors returning to reprise their roles Coming In January -2017 Preview Issu e No, they didn’t find the world’s biggest Wal-Mart. yearly for the Gordon Tootoosis Nikaniwin Theatre The feisty old ladies are actually taking over the 400 (GTNT). -

CNSF Congress Program

Information ▾ o Congress Details o Congress Registration o Hotel Reservations o Host City | Travel o Congress Dates Program ▾ o Program-at-a-Glance o Tuesday, June 21 o Wednesday, June 22 o Thursday, June 23 o Friday, June 24 o Grand Plenary Speakers Abstracts/Prizes ▾ o Call for Abstracts o Presentation Formats o 2016 Society Prize Winners Meetings & Events o Society & Business Meetings o Networking & Social Events MOC ▾ o Learning Objectives o Maintenance of Certification Sponsors & Exhibitors ▾ o Sponsor Information o Exhibitor Information Exhibit Hall ▾ o Industry Updates o On-Site Exhibits Committees ▾ o Board of Directors o Congress Planning Committee CNSF 51st Congress June 21-24, 2016 | Quebec City Convention Centre | Quebec City Congress Details The Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation hosts an annual Canadian Congress with four days of accredited scientific courses to assist our members, and others, with their Continuing Professional Development and Maintenance of Certification. This is a collegial meeting providing multidisciplinary courses relevant to all neuroscience specialties. Our 2016 meeting is at: Quebec City Convention Centre 900 René-Lévesque Blve. East Quebec City, Quebec G1R 2B5 QUESTIONS? Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation Membership, sponsorship, exhibiting at Congress: 143N - 8500 Macleod Trail, SE, Calgary, AB T2H 2N1 T: 403-229-9544 F: 403-229-1661 [email protected] Intertask Conferences Registration, speakers, exhibitor logistics: 275 rue Bay Street, Ottawa ON K1R 5Z5 T: 613-238-6600 F: 613-236-2727 [email protected] Registration Onsite Registration & Check-In Desk for Delegates and Exhibitors The Registration / Check – in desk is located on Level 2 of the Quebec Convention Centre. -

Memory, Space and the Individualizing Transformation of the Subject in Twenty-First-Century Mexican Fiction

Me acuerdo … ¿Te acuerdas?: Memory, Space and the Individualizing Transformation of the Subject in Twenty-First-Century Mexican Fiction Elsa Treviño Ramírez 1. Twenty-First-Century Transitions and the New Individual Since the mid-nineties, Mexican literature has witnessed a departure from a traditional interest in collectivizing discourses of identity. Particularly, the generation of writers born in the late 1960s and early 1970s has displayed a growing faith in individualism as a means to resist totalizing state-driven cultural visions (Raphael, 113), and as a crucial element of authorial freedom (Chimal). Literary critics have, in one way or another, identified individualism as the main characteristic of contemporary writing.1 Individual literary endeav- ours have replaced ideas about a homogenizing ‘literatura nacional’ (González Boixo, 17)2 that explores and assists in the definition of ‘lo mexicano’ (Bartra, 41), a vague ideological notion that would capture the ‘true’ characteristics and façon d’être – the spirit – of the Mexican people. As González Boixo explains: ‘[l]ibrados de la idea de nación, la nueva generación, “los nietos de Rulfo”, podrán escribir sobre cualquier tema, desde su preciado ‘individualismo’’(17).3 Opposing a triumphalist notion of unrestrained personal freedom however, twenty-first-century Mexican literature consistently shows anxiety- ridden and uprooted characters. The stories of these characters lay bare the struggle of the individual subject to construct her or his own identity when confronted with the limits of self-determination. Characters are placed at odds with the many social forces that determine and influence people’s lives without offering them anchorage or guidance. In addition, in a signifi- cant number of stories, characters are faced with their own desire and their embodied experience as elements that inform and constrain their self- representations. -

Esharp TRANS- TRANSITIONS, TRANSFORMATIONS, ‘TRANS’ NARRATIVES

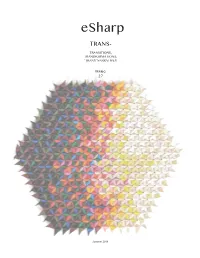

eSharp TRANS- TRANSITIONS, TRANSFORMATIONS, ‘TRANS’ NARRATIVES Issue 27 Summer 2019 2 3 eSharp TRANS- They say life can be represented by Birth and Death but for me (I say this because I’ve lived a quarter of it by now) , it’s also the colours that lie between black and white. This piece is my friend’s version of life represented in Origami where 2456 pieces of small paper are individually folded and interlocked together without any glue. She folded each paper in the cab, metro, flight and train while people stared at her trying to figure out what she’s up to without even looking at the pieces in her hand. She would continue to do so even if you blind fold her. She used 33 shades of colours to ge the best Ombré of life. How life transitions from birth with a pure white soul of a baby embracing various stages and colours of life and eventually goes down to a death a blunt black reality. ADITI ANUJ Aditi Anuj is origami enthusiast. They call her the Origami girl. Graduated from the reputed National school of Design in India she took on a journey to gold each piece of paper she touched to create a beautiful version of itself. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 08 A CRITICAL OVERVIEW OF FEMINISM AND/IN TRANSLATION: CONSTRUCTING CULTURES AND IDENTITIES THROUGH AN INTERDISCIPLINARY EXCHANGE CHARLOTTE LE BERVET (UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW) THE GAZE IN CASINO ROYALE: TRANSFORMATION FROM SUBJECT TO OBJECT IN 18 BOND’S NEW ALTERNATIVE MASCULINITY ITSNA SYAHADATUD DINURRIYAH (UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS) THE PERILS OF WORLD LITERATURE: ROBERTO BOLAÑO’S EXOTICISATION AND FALSE -

Annual March 27 – April 7, 2019

NJJFF sponsored by 19TH ANNUAL MARCH 27 – APRIL 7, 2019 TICKET INFORMATION SEATING POLICY FESTIVAL CO-CHAIRS Online Sponsor seating will begin 30 minutes prior to all Andrea Bergman, Joni Cohen jccmetrowest.org/njjff screenings. General admission ticket holders will Your printed receipt will serve as your ticket. be admitted 20 minutes prior to all screenings. In FESTIVAL CURATOR the event of a sell-out, a waiting list will be created. In Person Vicky Jacobs Visit the Box Office in the Gaelen Lobby, adjacent GENERAL INFORMATION to the Maurice Levin Theater on the first floor FESTIVAL COMMITTEE Films are not rated. Parental discretion is strongly of JCC MetroWest, Mondays and Thursdays, advised. Films designated “Adult Content” may Carol Churgin Abby Meth Kanter February 25–March 25, 10:00am–12:00pm. contain sexual content, explicit language and/ Myrna Comerchero Deborah Prinz Boxofficetickets.com fees apply. or violence. The NJJFF is not responsible for lost Michele Dreiblatt Ruth Ross or stolen tickets. Sorry, no refunds or exchanges. Nancy Fisher Evelyn Rothfeld Ticket Prices Festival programs are subject to change/ Robin Florin Sue Z Rudd General Seating: $13 cancellation without prior notice. For film trailers Caren Ford Sara-Ann Sanders Student, Senior, Matinee (before 5:00pm): $11 and the most up-to-date information about festival Herbert Ford Rickey Slezak At the Door events, visit our website or call the Film Festival Terri Friedman Dorit Tabak hotline at 973-530-3417. Tickets may be purchased at the theater venue Max Kleinman Neimah Tractenberg starting 45 minutes prior to screening, ALL FOREIGN FILMS HAVE ENGLISH SUBTITLES.