Early-Chapters-–-SIMPLY-BRILLIANT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiny Temple Lucky No

72 / 54 TINY TEMPLE LUCKY NO. 72 After many changes, Dan Pehrson Mormons hope replica in Salt Lake finds a home racing late models City will help improve public’s at Magic Valley Speedway. Partly cloudy. understanding. >>> RELIGION 1 >>> SPORTS 1 SPORTS 4 UNEMPLOYMENT CONTINUES TO FALL >>> Idaho jobless rate drops for third straight month, MAIN 4 SATURDAY 75 CENTS June 5, 2010 TIMES-NEWS Magicvalley.com College basketball TEACHER PAY CUT 7.8% coaching legend Twin Falls School Board makes decision on 4-1 vote John Wooden dies By Ben Botkin By Beth Harris As a coach, he was a Times-News writer Associated Press writer groundbreaking trendsetter who demanded his players The Twin Falls School LOS ANGELES — John be in great condition so they Board on Friday decided that Wooden, college basket- could play an up-tempo the only realistic way to ball’s gentlemanly Wizard style not well-known on weather the downturn in of Westwood who built one the West Coast at the time. state funding is to use fur- of the greatest dynasties in But the Wizard’s legacy lough days to slash teacher all of sports at UCLA and extended well beyond that. pay by an average of 7.8 per- became one of the most He was the master of the cent. revered coaches ever, has simple one- or two-sen- The school board made its died. He was 99. tence homily, instructive decision with a 4-1 vote, The university said little messages best pre- with Trustee Richard Wooden died Friday night sented in his famous Crowley dissenting. -

Putting Autism to Work

Ultrasonic breast cancer detection device headed to market, Page 3 MAY 16-22, 2016 Big plans where projects once towered Putting Brewster-Douglass redevelopment is largest for Amin Irving’s Ginosko By Kirk Pinho been unheard of as the poor then [email protected] were corralled into concentrated autism When Amin Irving’s mother, a areas. teacher education professor at While he may not be a house- Michigan State University, died in hold name like Dan Gilbert, one of 1995 two months after he graduat- the other Choice Detroit LLC devel- ed from East Lansing High School, opment partners, Irving has to work his real estate career was born. racked up a steady string of low-in- It’s been more than two decades come housing developments in since he sold his mother’s acquisitions since founding his 1,200-square-foot home on Abbot Novi-based Ginosko Development Steven Glowacki has three degrees, an IQ Road south of Saginaw Street, and Co. in 2003. of 150 and knocked his CPA exam out of now Irving, 39, is embarking on his So his involvement should the park. But he can’t nd a job. largest ground-up construction come as little surprise. PHOTO BY LARRY PEPLIN plan to date: a $267 million project Irving, the father of three young as part of a joint venture to devel- children, has been well respected op 900 to 1,000 of mixed-income in the affordable housing fi eld for housing units on the site of the years, said Andy Daitch, senior Disorder’s growing population seeks place in job market former Brewster-Douglass housing vice president of investments for projects and in Eastern Market. -

Swedish House Mafias “Don't You Worry Child” Passerer 1 Millioner Solgte Kopier

21-11-2012 12:56 CET Swedish House Mafias “Don’t You Worry Child” passerer 1 millioner solgte kopier Den svenske stjernegruppen Swedish House Mafia kan i dag annonsere at singelen ”Don’t You Worry Child” har passert 1 millioner solgte kopier verden over på 9 uker. I Norge har singelen i skrivende stund solgt til 3x platina og over 4 millioner streams på Spotify. Denne helgen besøker avskjedsturnéen ”One Last Tour” Stockholm, hvor Swedish House Mafia spiller sine tre siste konserter på svensk jord for mer enn 105 000 fans. Billettene ble utsolgt på få timer. Fredag kveld gjester gruppen TV-programmet ”Skavlan” på NRK1. Swedish House Mafia spiller på Telenor Arena utenfor Oslo lørdag 22 desember, dette blir gruppens siste konsert noensinne i Europa. Se innebygd innhold her Live-video "Don't You Worry Child: Se video på YouTube her EMI er ett av verdens største og eldste plateselskaper. Blant våre internasjonale artister finner du The Beatles, Pink Floyd, David Bowie, Katy Perry, Robyn, Coldplay, David Guetta, Swedish House Mafia, Roxette, Kim Larsen, Tinie Tempah, Adam Tensta, Alice In Chains, LCD Soundsystem, Deadmau5, The Kooks, 30 Seconds To Mars, Jane’s Addiction, Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Rise To Remain, Iron Maiden m.fl. Blant våre norske artister finner du, Åge Aleksandersen, Susanne Sundfør, Marit Larsen, Henning Kvitnes, Hellbillies, Frida Amundsen, Lars Haavard Haugen, Madrugada, Dumdum Boys, Morten Abel, Halvdan Sivertsen m.fl Kontaktpersoner Matea Grøvik Pressekontakt Prosjektleder [email protected] + 47 478 65 722 Mona Olsen Pressekontakt Senior Project Manager Domestic [email protected] +47 95 82 54 20 Yordana Jakobsen Pressekontakt International Project Manager [email protected] +47 47 30 64 73. -

The Radicals and the Renaissance Nationalistic, Class Conscious, and International-Minded Than Were 5· Can-Born Blacks."84

=":S'" ttlt:;J UI;;I;;U lllgllly lj~fieficia1 to Harlem-and to America at Essays focusing on the contributions of Caribbean Americans to Harlem the United States would not have called attention to Huiswoud's and "gifts" to the Third International. Domingo and his colleagues however, the significance of the 1922 Moscow congress in placing the ofall peoples ofAfrican descent on the international agenda. Wayne F. per has noted that "the official stance of the Comintern regarding 1922 was influenced by West Indians, who were simultaneously much The Radicals and the Renaissance nationalistic, class conscious, and international-minded than were 5· can-born blacks."84 When the first version ofDomingo's article was issued in March 1925, ofthe four veteran radicals were positioned to wage their campaign racism and colonialism on many fronts as functionaries of organizati( allied with the Workers Party, such as the ANLe. Hermie was also now tiorred to join the group. She had graduated from high school in 1924 through Huiswoud had become friendly with his close comrades and As Hermie Dumont approached her twentieth birthday in 1925 she was be to radical politics along with the gifts ofwriters and artists in Harlem. ginning to appreciate that she was in the midst of a vibrant, eclectic, creative Huiswoud went to Chicago to help launch the ANLC he asked her to community. Bold print on the cover ofthe March 1925 Survey Graphic mag for him. And she did. azine declared "Harlem-Mecca of the New Negro" and included interest ing short stories and other writings by people she had met or recognized from meetings, newspaper articles, or just walking down the street. -

Tim Minchin with West Australian Symphony Orchestra Apart / Together

WORLD PREMIERE TIM MINCHIN WITH WEST AUSTRALIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA APART / TOGETHER Image: Damian Bennett Perth Festival acknowledges the Noongar people who continue to practise their values, language, beliefs and knowledge on their kwobidak boodjar. They remain the spiritual and cultural birdiyangara of this place and we honour and respect their caretakers and custodians and the vital role Noongar people play for our community and our Festival to flourish. Stay COVID-19 safe 1.5m Physical distancing Wash your hands Stay home if you are sick Register your attendance For latest health advice visit healthywa.wa.gov.au/coronavirus TIM MINCHIN WITH WEST AUSTRALIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA APART / TOGETHER KAARTA KOOMBA / PERTH CBD KINGS PARK & BOTANICAL GARDEN M T W T F S S FEBRUARY 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Sat & Sun Gates open 5.30pm Tim Minchin 7pm Duration 80mins With thanks to Mellen Events and Kings Park & Botanic Garden CONTENTS CONTENTS CONTENTS WELCOME WELCOME 6 Welcome 8 Credits 10 Repertoire CREDITS BACKGROUND 12 Apart Together - The Album REPERTOIRE BIOGRAPHIES 20 Tim Minchin 22 Jessica Gethin BACKGROUND 24 West Australian Symphony Orchestra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 26 Perth Festival Partners BIOGRAPHIES 27 Perth Festival Donors * Just tap the interactive tabs on the left to skip to a specific section ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS WELCOME Image: Jess Wyld CREDITS Perth Festival 2021 is a love song to this place – its people, artists and stories. And so, it is fitting that one of our city’s favourite sons (and a dear friend of many REPERTOIRE of us in the Festival family and beyond) is back in town to perform a special version of his very personal album Apart / Together. -

14-15-Frontoffice.Pdf

7 Chairman . .. Dan Gilbert Vice Chairmen . Jeff Cohen, Nate Forbes General Manager . David Griffin Assistant General Manager . .. Trent Redden Head Coach . David Blatt Associate Head Coach . Tyronn Lue Assistant Coaches . Jim Boylan, Bret Brielmaier, Larry Drew, James Posey Director, Pro Player Personnel . Koby Altman Director, Player Administration . Raja Bell Scouts . Pete Babcock, Stephen Giles, David Henderson Director, Strategic Planning . Brock Aller Manager, Basketball Administration & Team Counsel . Anthony Leotti Executive Administrator-Player Programs and Logistics . Randy Mims Director, International Scouting . Chico Averbuck Senior Advisor, Scout . Bernie Bickerstaff Director, Player Development/Assistant Coach . Phil Handy Assistant Director, Player Development . Vitaly Potapenko High Performance Director . Alex Moore Coordinator, Athletic Training . Steve Spiro Assistant Athletic Trainer, Performance Scientist . Yusuke Nakayama Coordinator, Strength & Conditioning . Derek Millender Athletic Performance Liaison . Mike Mancias Team Physicians . Richard Parker, MD, Alfred Cianflocco, MD Team Dentists . Todd Coy, DMD, Ray Raper, DMD Physical Therapist . George Sibel Director, Team Security . Marvin Cross Director, Executive Protection . .. Robert Brown Manager, Team Security . Rod Williams Executive Protection Specialists . Michael Pearl, Jason Daniel Director, Analytics . Jon Nichols Director, Team Operations . Mark Cashman Coordinator, Equipment/Facilities . Michael Templin Senior Manager, Practice Facility . David Painter -

Chained but Untamed

SPECIAL REPORT INTERNATIONAL BANKING May 14th 2011 Chained but untamed SRInternationalBanking2011.indd 1 03/05/2011 17:40 S PECIAL REPORT I NTERNATIONAL BANKING Chained but untamed The world’s banking industry faces massive upheaval as post•crisis reforms start to bite. They may make it only a little safer but much less protable, says Jonathan Rosenthal THE NEAR•COLLAPSE of the world’s banking system two•and•a•half years ago has prompted a fundamental reassessment of the industry. Per• haps the biggest casualty of the crisis has been the idea that nancial markets are inherently self•correcting and best left to their own devices. After decades of deregulation in most rich countries, nance is entering a new age of reregulation. This special report will focus on these regula• tory changes, which will be the main determinant of the banks’ prot• ability over the next few years. Start with the additional capital that banks around the world will have to hold. Bigger capital cushions will make the system somewhat saf• er, but they may also reduce banks’ protability by as much as a third. In addition, they may push up borrowing costs and slow economic growth. Worse, higher capital requirements for banks may drive risk into the darker corners of nan• C ONTENTS cial markets where it may cause even greater harm. 3 Reregulation Supervisors and regulators almost everywhere are A dangerous embrace still trying to nd ways to deal with banks that have be• come too big or too interconnected to be allowed to fail. 5 Japanese banks If anything, the crisis has exacerbated this problem. -

Brevard Live March 2012

Brevard Live March 2012 - 1 2 - Brevard Live March 2012 Brevard Live March 2012 - 3 4 - Brevard Live March 2012 Brevard Live March 2012 - 5 6 - Brevard Live March 2012 Content march 2012 FEATURES page 51 LES DUDEK CY CURNIN Columns During the 70s and 80s, Les Dudek made The Fixx, lead by Cy Curnin, hit the charts with flashy hits like “One Thing Charles Van Riper waves as one of the hottest guitar players Political Satire on the rock scene. He loaned his talent to Leads to Another,” “Saved By Zero” 20 famous performers like Boz Scaggs and and “Red Skies.” Matt Bretz recently Calendars Steve Miller. With 6 solo albums under talked to Curnin. his belt, he’s now part of rock history. Page 16 23 Live Entertainment, Page 10 Concerts, Festivals THE MOODY BLUES PADDLE BOARDING Chris Long Paddle boarding has just started to come 28 Political Blog Since the 60s, as a part of the histor- into the limelight with its enjoyable ath- ic original British invasion of Super letic characteristics and the rider’s spirited Brevard Scene groups, The Moody Blues have lit up unity with the water. Joe Cronin checked We’re Out There! the hearts and minds of millions of rock it out. 31 fans creating soundtracks of our lives. Page 39 Page 13 Out & About Brevard’s vibrant CHRISTOPHER BREWER 37 club & restaurant GLEN CAMPBELL scene He’s been a legend in country music. He is an artist with a very distinct and recognizable style who has been on a Just recently he announced that he has Life & The Beach Alzheimer’s. -

Eagle 2009 Temp

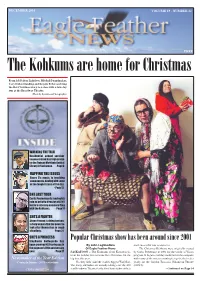

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 19 - NUMBER 12 FREE The Kohkums are home for Christmas From left Dalton Lightfoot, Mitchell Poundmaker, Cory Dallas Standing and Krystle Pederson bring the Rez Christmas story to a close with a four day run at the Broadway Theatre. (Photo by Sweetmoon Photography) WALKING THE TALK Residential school survivor Eugene Arcand has high praise for the Frances Morrison Central Library in Saskatoon. - Page 3 RAPPING THE ISSUES Beary D’s music is touching some nerves, dealing with some of the tough issues of the day . - Pag e 12 ONE LAST TOUR Curtis Peeteetuce is leaving his role as artistic director of GTNT but he’s enjoying one more fling with the Kohkums. - Page 14 SHE’S A FIGHTER Shana Pasapa is doing her best to help women find the power to look after themselves in tough situations. - Page 21 SHE’S A PRINCESS Popular Christmas show has been around since 2001 Stephanie Bellegarde has been crowned FSIN princess in By John Lagimodiere most successful tour season ever. the pageant’s 70th anniversary Of Eagle Feather News The Christmas Kohkoms were originally created year. - P age 27 SASKATOON – The Kohkums from Kitweenook, by Curtis Peeteetuce in 2001 for the Circle of Voices from the holiday fan favourite Rez Christmas, hit the program. It began a holiday tradition for the company Newsmaker of the Year Edition big time this year. with many of the actors returning to reprise their roles Coming In January -2017 Preview Issu e No, they didn’t find the world’s biggest Wal-Mart. yearly for the Gordon Tootoosis Nikaniwin Theatre The feisty old ladies are actually taking over the 400 (GTNT). -

Pandemic Profiteers: Under Trump Michigan Billionaire Wealth Soars, Local Communities Suffer ______

Pandemic Profiteers: Under Trump Michigan Billionaire Wealth Soars, Local Communities Suffer ____________________________________________________________________________________ While communities across Michigan have been ravaged by the health and economic crises created by Trump’s botched COVID-19 response,1 the state’s billionaires have actually increased their collective wealth since the start of the pandemic. Since confirming the state’s first case on March 10th, over 122,000 Michiganders have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and nearly 7,000 people have died.2 The State’s pre-pandemic unemployment rate was just 2.1%, but as of August 15th it stood at 10.7% and went as high as 24% in April.3 Michigan’s Black communities have been hit the hardest. The results of years of divestment and systemic racism coupled with COVID-19 have been brutal. In the second quarter of 2020, Michigan had the highest Black unemployment rate of any US state, a staggering 35.5%.4 This job loss was against the backdrop of the pandemic, which has also hit Michigan’s Black communities hardest. Despite making up 14% of the state's population, Black community members represent over 40% of Michigan’s COVID deaths.5 Meanwhile, five of Michigan’s eight billionaires saw their net worth surge by an estimated $43.6 billion, a 360% increase, since the beginning of the pandemic.6 Two of Michigan’s billionaires with some of the largest increases in their wealth are well connected to the Trump Administration. Recent revelations about Trump’s decades-long tax avoidance schemes -

2017 UK Neds A4 Redone CO2.Indd

The Class of 2016 New NEDs in the FTSE 350 2 FOREWORD At the time I took on my first non-executive role on a FTSE 350 Board, Tony Blair was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Steve Jobs had not yet launched the iPhone, and most of us were blissfully unaware of terms such as sub-prime lending, securitisation and credit default swaps. It is hard to believe that the year was 2006, barely over a decade ago. Bob Dylan told us that “times are a-changing” in 1964. But times are certainly changing faster now. From a corporate perspective, it is this speed of evolution – driven by economic, societal, political or technological developments – that keeps management teams and Boards up at night. However, more often than not, what appear as sudden, unexpected changes are but an aggregate of gradual, incremental steps. It is when we do not spot the early “movements” and premonitory signs of change that we find ourselves dangerously exposed to something that, in hindsight, should have been visible to those who had paid attention. As a Chief Executive and a Non-Executive Director I have always looked for those tools that could give me the “upper-hand” in dealing with the unknown and the unexpected. It is for this reason that I welcome The Class of report series published yearly by Korn Ferry. By analysing the small incremental changes occurring from one year to the next in the skills and backgrounds of each new generation of FTSE 350 Directors, and interpreting them in the context of the underlying trends of the past ten years, the Class of provides insight into how our Boards are evolving and, therefore, where companies and – by extension – societies are heading. -

CNSF Congress Program

Information ▾ o Congress Details o Congress Registration o Hotel Reservations o Host City | Travel o Congress Dates Program ▾ o Program-at-a-Glance o Tuesday, June 21 o Wednesday, June 22 o Thursday, June 23 o Friday, June 24 o Grand Plenary Speakers Abstracts/Prizes ▾ o Call for Abstracts o Presentation Formats o 2016 Society Prize Winners Meetings & Events o Society & Business Meetings o Networking & Social Events MOC ▾ o Learning Objectives o Maintenance of Certification Sponsors & Exhibitors ▾ o Sponsor Information o Exhibitor Information Exhibit Hall ▾ o Industry Updates o On-Site Exhibits Committees ▾ o Board of Directors o Congress Planning Committee CNSF 51st Congress June 21-24, 2016 | Quebec City Convention Centre | Quebec City Congress Details The Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation hosts an annual Canadian Congress with four days of accredited scientific courses to assist our members, and others, with their Continuing Professional Development and Maintenance of Certification. This is a collegial meeting providing multidisciplinary courses relevant to all neuroscience specialties. Our 2016 meeting is at: Quebec City Convention Centre 900 René-Lévesque Blve. East Quebec City, Quebec G1R 2B5 QUESTIONS? Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation Membership, sponsorship, exhibiting at Congress: 143N - 8500 Macleod Trail, SE, Calgary, AB T2H 2N1 T: 403-229-9544 F: 403-229-1661 [email protected] Intertask Conferences Registration, speakers, exhibitor logistics: 275 rue Bay Street, Ottawa ON K1R 5Z5 T: 613-238-6600 F: 613-236-2727 [email protected] Registration Onsite Registration & Check-In Desk for Delegates and Exhibitors The Registration / Check – in desk is located on Level 2 of the Quebec Convention Centre.