Capping Nashville's I-40 South Loop to Connect Downtown and Midtown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Route 66 Auto Tour — Williams to Flagstaff, Arizona Williams Ranger District Kaibab National Forest

Southwestern Region United States Department of Agriculture RG-3-07-07 Forest Service July 2013 Historic Route 66 Auto Tour — Williams to Flagstaff, Arizona Williams Ranger District Kaibab National Forest Points of Interest Take a trip back in time, to a day when driving across America meant finding adventure and freedom on the open road. Imagine what it was like when Arizona’s first tourists saw scenic wonders like the Navajo Indian Reservation, Petrified Forest, Grand Canyon National Park, and pine-laden Kaibab National Forest. Cruise down memory lane and discover the past on Historic Route 66. Williams served travelers on Route 66 as part of the “Main Street of America.” Now called Bill Williams Avenue in this picturesque western town, the historic road is still lined with businesses dating from the highway’s heyday. In 1984, Williams became the last Route 66 town in America to be bypassed by Interstate 40. The tour winds through beautiful scenery toward Bill Williams Mountain. Interstate 40 now covers this section of Route 66 at Davenport Lake. Pittman Valley was first settled by ranchers in the 1870s. Tourists found guest cabins and a gas station along the road here. Historic Route 66 Auto Tour ― Williams to Flagstaff, AZ 1 Garland Prairie Vista has a beautiful view of the San Francisco Peaks, the highest mountains in Arizona. A favorite with photographers, this view appeared on many Route 66 postcards. Parks is a small community that started out as a railroad stop in the 1880s and later became a wayside for highway tourists. When the highway was thriving, the area had a Forest Service campground, several motels, gas stations, curio shops, and a road that led north to the Grand Canyon. -

Revised Application Prop Designation of I-840.Pdf

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials An Application from the State Highway or Transportation Department of Tennessee for: Elimination of a U.S. (Interstate) Route AASHTO Use Only Establishment of a U.S. (Interstate) Route I-840 Action taken by SCOH: Extension of a U.S. (Interstate)Route Relocation of a U.S. (Interstate) Route Establishment of a U.S. Alternate Route Establishment of a Temporary U.S. Route **Recognition of a Business Route on U.S. (Interstate) Route **Recognition of a By-Pass Route on U.S. Route Between Interstate 40 exit 176 and Interstate 40 exit 235 The following states or states are involved: Tennessee • **“Recognition of…”A local vicinity map needed on page 3. On page 6 a short statement to the effect that there are no deficiencies on proposed routing, if true, will suffice. • If there are deficiencies, they should be indicated in accordance with page 5 instructions. • All applications requesting Interstate establishment or changes are subject to concurrence and approval by the FHWA DATE SUBMITTED: SUBMIT APPLICATION ELECTRONICALLY TO [email protected] • *Bike Routes: this form is not applicable for US Bicycle Route System The purpose of the United States (U.S.) Numbered Highway System is to facilitate travel on the main interstate highways, over the shortest routes and the best available roads. A route should form continuity of available facilities through two or more states that accommodate the most important and heaviest motor traffic flow in the area. The routes comprising the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways will be marked with its own distinctive route marker shield and will have a numbering system that is separate and apart from the U.S. -

Interstate 40 Median Regrade Project Initial Study

Interstate 40 Median Regrade Project San Bernardino County, California District 08-SBd-40 (PM R100.0/R125.0) EA 08-0R141/PN 0815000200 Initial Study [with Proposed] Mitigated Negative Declaration Prepared by the State of California Department of Transportation September 2020 This page intentionally left blank. General Information About This Document What’s in this document: The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) has prepared this Initial Study, which examines the potential environmental impacts of alternatives being considered for the proposed project in San Bernardino County, California. The project is to regrade the existing median cross slope which vary from 2:1 to 6:1 or steeper gradient to 10:1 or flatter on Interstate 40 (I-40) from Post Mile (PM) R100.0 to PM R125.0. The document describes the project, the existing environment that could be affected by the project, potential impacts from the project, and proposed measures. What you should do: • Please read this document. • Additional copies of this document are available for review during regular business hours at the Needles Branch Library, 1111 Bailey Avenue, Needles, CA 92363, and at Caltrans District 8, 464 West 4th Street, San Bernardino, 92401. • We welcome your comments. If you have any comments about the proposed project, please send your written comments to Caltrans by the deadline below. • Submit comments via U.S. mail to Caltrans at the following address: Gabrielle Duff, Senior Environmental Planner California Department of Transportation, District 8 464 West 4th Street San Bernardino, CA 92401-1400 • Submit comments via email to: [email protected] • Submit comments by the deadline: October 26, 2020. -

American Indians & Route 66

American Indians & Route 66 AMERICAN INDIANS & ROUTE 66 | 01 ON OUR COVER: ‘SEEING THROUGH THE PATTERNS’ Geraldine Lozano is a conceptual artist based out of Brooklyn, New York. She works using photo, video performance, artist books, and public art in her practice. Her video installation work has been funded by the Creative Work Fund and the Zellerbach Foundation of San Francisco, California. Lozano’s public art can be seen in the architecturally integrated art of eco-resin screens set into the bus shelters of BRIO, Sun Metro’s new rapid transit system. Gera, as she as also known in the street art world, creates femenine artwork that is conscious and provocative. Her studio work and public art work reflect the spirit of culture and dreams. – www.geralozano.com American Indians & Route 66 AMERICAN INDIANS & ROUTE 66 | 01 MAP KEY Route 66 American Indian Reservation Tribal Jurisdictions (Oklahoma) Trust Land ABOUT THIS MAP Route 66 cartography provided by Pueblo of Sandia GIS Program, Pueblo of Sandia, Bernalillo, New Mexico Route 66 historic alignment information derived from National Park Service data and Rick Martin’s online resource, http://route66map. publishpath.com/ Tribal land status and base mapping provided by Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Trust Services Division of Water and Power DID DIDYOU YOUKNOW? KNOW? DID YOU KNOW? INTRODUCTION AMERICAN INDIANS AND ROUTE 66 Route 66 was an officially commissioned highway from 1926 Route 66 begins in Grant Park, Chicago—or ends there— to 1985. During its lifetime, the road guided travelers through depending on which direction you’re traveling. At the intersection the lands of more than 25 tribal nations. -

Route 66 Economic Impact Study Contents 6 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi Ts

SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey June 2011 AUTHORS David Listokin and David Stanek Kaitlynn Davis Michael Lahr Orin Puniello Garrett Hincken Ningyuan Wei Marc Weiner with Michelle Riley Andrea Ryan Sarah Collins Samantha Swerdloff Jedediah Drolet Charles Heydt other participating researchers include Carissa Johnson Bing Wang Joshua Jensen Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey ISBN-10 0-9841732-3-4 ISBN-13 978-0-9841732-3-5 This report in its entirety may be freely circulated; however content may not be reproduced independently without the permission of Rutgers, the National Park Service, and World Monuments Fund. 1929 gas station in Mclean, Texas Route 66 Economic Impact Study contents 6 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi ts 16 SECTION TWO Tourism and Travelers 27 SECTION THREE Museums and Route 66 30 SECTION FOUR Main Street and Route 66 39 SECTION FIVE The People and Communities of Route 66 51 SECTION SIX Opportunities for the Road 59 Acknowledgements 5 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi ts unning about 2,400 miles from Chicago, Illinois, to Santa Monica, California, Route 66 is an American and international icon, myth, carnival, and pilgrimage. -

![[Archived] Oklahoma: I-40 Crosstown / ACCT Workshop](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3904/archived-oklahoma-i-40-crosstown-acct-workshop-2743904.webp)

[Archived] Oklahoma: I-40 Crosstown / ACCT Workshop

accepted or practice. or current Archival guidance reflect policy, longer no May regulation, Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1: ACTT GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DETAILS ...................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Corridor Analysis ................................................................................................................ 9 2.2 Alternate D-The Locally Preferred Alternate ...................................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3: WORKSHOP MEETING DETAILS ................................................................................................ 17 3.1 Opening Session .............................................................................................................accepted.. 18 3.2 Workshop Process and Recommendations ....................................................................... 18 3.2.1 Railroad/Utilities ...............................................................................................................or practice. 18 3.2.2 Structures/Geotechnical ................................................................................................... -

Arizona Transportation History

Arizona Transportation History Final Report 660 December 2011 Arizona Department of Transportation Research Center DISCLAIMER The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Arizona Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Trade or manufacturers' names which may appear herein are cited only because they are considered essential to the objectives of the report. The U.S. Government and the State of Arizona do not endorse products or manufacturers. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-AZ-11-660 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date December 2011 ARIZONA TRANSPORTATION HISTORY 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author 8. Performing Organization Report No. Mark E. Pry, Ph.D. and Fred Andersen 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. History Plus 315 E. Balboa Dr. 11. Contract or Grant No. Tempe, AZ 85282 SPR-PL-1(173)-655 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13.Type of Report & Period Covered ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 206 S. 17TH AVENUE PHOENIX, ARIZONA 85007 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Project Manager: Steven Rost, Ph.D. 15. Supplementary Notes Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration 16. Abstract The Arizona transportation history project was conceived in anticipation of Arizona’s centennial, which will be celebrated in 2012. Following approval of the Arizona Centennial Plan in 2007, the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) recognized that the centennial celebration would present an opportunity to inform Arizonans of the crucial role that transportation has played in the growth and development of the state. -

Interstate 80 Freight Corridor Analysis

FINAL REPORT FHWA-WY- 09/09F Interstate 80 Freight Corridor Analysis Current Freight Traffic, Trends and Projections for WYDOT Policy-makers, Planning, Engineering, Highway Safety and Enforcement R Prepared by: & R&S Consulting S Consulting PO Box 302 Masonville, CO 80541 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration State of Wyoming Department of Transportation December 2008 Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author(s) who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Wyoming Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. The United States Government and the State of Wyoming do not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objectives of the document. Quality Assurance Statement The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides high-quality information to serve government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. ii Report No. FHWA – WY-09/09F Government Accession No. Recipients Catalog No. -

The Highway to Segregation by Sabre J. Rucker Thesis Submitted to The

The Highway to Segregation By Sabre J. Rucker Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Medicine, Health, and Society May, 2016 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Aimi Hamraie Juleigh Petty Laura Stark ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor Doctor Aimi Hamraie of the Center of Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University. The door to Professor Hamraie’s office was always open. They always steered me in the right direction whenever they thought I needed it. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee Professor JuLeigh Petty and Professor Laura Stark of the Center of Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University. I am indebted to all of your valuable comments and encouragement. Finally I must express my gratitude to my parents and to my family for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank You. Sabre J. Rucker TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... iii Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 Methods............................................................................................................................................3 -

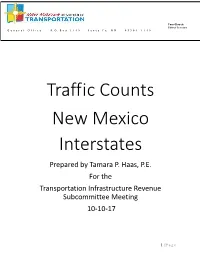

Traffic Counts New Mexico Interstates Prepared by Tamara P

Tom Church Cabinet Secretary G e n e r a l O f f i c e P. O. B o x 1 1 4 9 S a n t a F e, N M 8 7 5 0 4 – 1 1 4 9 Traffic Counts New Mexico Interstates Prepared by Tamara P. Haas, P.E. For the Transportation Infrastructure Revenue Subcommittee Meeting 10-10-17 1 | Page New Mexico Interstate Traffic 2016 12,700 AADT 10% trucks 38,000 AADT 20,000 AADT 12% trucks 30% trucks 14,800 AADT 40% trucks I-40 I-25: 202,000 I-40: 204,000 11,800 AADT 12% trucks I-25 15,600 AADT 30% trucks I-10 32,400 AADT 22% trucks AADT is the Average Annual Daily Traffic which includes cars and semi- trucks. 2 | Page Interstate 10 Traffic Interstate 40 Traffic I-10 begins at the Arizona State line and ends I-40 begins at the Arizona state line and ends at the Texas State Line. I-10 is 164.26 miles at the Texas state line. I-40 is 373.53 miles long. long. Arizona to Las Cruces: Arizona to Albuquerque (Big-I): AADT=15,600. AADT=20,000 30% trucks 30% trucks The total traffic has been consistent The total traffic has experienced over the past five years on this growth of 2%. portion of I-10. Albuquerque Metro Area: Las Cruces (I-25) to the Texas state line: AADT = 204,000 at I-25 AADT=32,400. Number of trucks is consistent 22% trucks through the metropolitan area; The traffic has experienced growth however, the % of trucks is less due of 2% per year. -

I-40 Douglas Boulevard Interchange Reconstruction and Related Widening Oklahoma County, Oklahoma

I-40 Douglas Boulevard Interchange Reconstruction and Related Widening Oklahoma County, Oklahoma Submitted Previously for FASTLANE? YES Project on NHFN? Yes/no YES Name in Previous Application Same Project Name Project on NHS? Yes/no YES Previously Incurred Project Cost: $4,909,700 Project to add Interstate capacity? Yes/no YES Future Eligible Project Cost: $122,220,000 Project in national scenic area? Yes/no NO Total Project Cost: $127,129,700 Rail grade crossing or separation included? NO FASTLANE Request: $73,332,000 Intermodal or freight rail project, or freight project Total Federal Funds (incl. FASTLANE) $97,776,000 within freight rail, water, or intermodal facility? NO Matching funds restricted to If yes, specify: specific project component? NO NSFHP $ to be spent on above two items: N/A I-40 Douglas FASTLANE Application submitted by the Oklahoma Department of Transportation, 2017 Supporting information can be found at: https://www.ok.gov/odot/Progress_and_Performance/Federal_Grant_Awards/FASTLANE_Grants.html ODOT Contact: Matthew Swift, SAPM Division Engineer, ODOT. (405) 521-2704 email: [email protected] State Oklahoma Inclusion in Planning Documents: Begin Lat/Long: 35˚26'0"N, 97˚22'30"W TIP: NO* End Lat/Long: 35˚24'8 "N, 97˚17'17"W STIP: NO* Size of project: Large MPO LRTP: YES Urbanized Area (UA): Oklahoma City State LRTP: YES UA population, 2014 919,230 State Freight Plan: NA * Elements of this project are included in the current STIP and TIP documents i I-40 Douglas FASTLANE Application submitted by Oklahoma Department of Transportation, 2017 ii Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ -

Transportation Improvement Corridors in This Plan Utilized the Following Method

CHAPTER 7: TRANSPORTATION CORRIDORS 7.0 DEFINITIONS Three types of transportation corridors are identified in the 2005-2030 Oklahoma Statewide Intermodal Transportation Plan: • Transportation Improvement Corridors: These are highway corridors where projected traffic volumes indicate additional capacity will be needed by 2030. • National High Priority Corridors: These are Congressionally-identified corridors of national significance. There are four such corridors in Oklahoma: (1) US 287 [Ports-to-Plains Corridor] from Texas to Colorado in Cimarron County; (2) US 54 [TransAmerica Corridor] from Texas to Kansas in Texas County; (3) I-35 from Texas to Kansas; and, (4) US 412 from Tulsa to Memphis, Tennessee. These corridors are eligible for special discretionary funding from the National Corridor Planning and Development (NCPD) program. • Freight Operational Improvement Corridor: These corridors represent highways with high truck traffic but do not indicate capacity needs by 2030. However, the efficiency of the these corridors is compromised by conditions such as stops in towns and cities, bridge deficiencies, geometrics, urban speed zones, school zones, at grade rail crossings, or other operating conditions that reduce the efficiency of freight movements. These corridors can benefit from corridor studies and improvements from a menu of improvements such as bypasses; intelligent transportation systems for driver information on traffic flows, weather conditions, etc.; bridge upgrades; rail grade separations; signal timing; and, geometric roadway improvements. 7.1 TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENT CORRIDORS 7.1.1 Definition The Transportation Improvement Corridors are highway corridors needing capacity upgrades by 2030. Transportation Improvement Corridors were first identified in the 1995 Oklahoma Statewide Intermodal Transportation Plan and resulted in the policy “To provide for continued safe and efficient movement, the plan includes the development from two to four lanes along the corridors”.