J.R.B. Stewart an Archaeological Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

191 No. 165. the WELLS LAW. in Exercise of the Powers Vested In

191 No. 165. THE WELLS LAW. CAP. 312 AND LAWS 19 OF Ι 95 Ι AND 42 OF 1953. ORDER BY THE GOVERNOR UNDER SECTION 3A. In exercise of the powers vested in him by section 3A of the Wells Law, His Excellency the Governor hereby defines for the purposes of the said section the areas set out in the Schedule hereto as areas in which no permit for the sinking or construction of a well shall be issued by the Commissioner and no variation or modification of any condition or restriction imposed on any such permit shall be effected, save with the concurrence of the Director of Water Development, in accordance with the provisions of the said section. 2. Notice under section 3A (2) of the Wells Law in respect of this Order was published in Supplement No. 3 to the Gazette of the 15th December, 1955· SCHEDULE. Defined Area. In the villages of Kato Polemidhia, Ypsonas, Erimi, Kolossi, Episkopi, Trakhoni, Zakaki, Cherkez Chiftlik, Asomatos, Akrotiri and Limassol Town, in the District of Limassol, the area within the following boundary, that is to say :— The boundary commences at milepost No. 63 on the main road from Ktima Town to Limassol Town and proceeds in a northeasterly direction along the said main road through the village of Episkopi to the north eastern corner of plot No. 179 of the Government Survey Plan No. LIV.57, locality " Koutsoulia ", (on the municipal boundary of Limassol Town) ; thence eastwards along the Paphos Street and Yildiz Street of the said Town to the junction of the last mentioned street with the Ismet Pasha Street; thence southeastwards along the last mentioned street and Gazi Pasha Street to the junction of the last mentioned street with the Kio pruluzade Street ; thence southwards and southwestwards along the last mentioned street and Ayios Antonios Street (towards the Petroleum Store) to the seashore ; thence in a southerly direction along the sea ar shore to a point 1,033 y ds approximately southsoutheast of the Govern ment Survey triangulation point " Ktista " on the Government Survey Plan No. -

Cyprus Guide 1.10.18.Indd

Cyprus Explore. Dream. Discover. 1 Pissouri Bay Our charming hideaway Paphos The mythological labyrinth Limassol Cultural cosmopolitanism Wine Routes Discover the world of wine at your fi ngertips Chef’s Kitchen Mouth-watering recipes Troodos Off the beaten track Nicosia Fortifi ed by history and fresh ideas Tips from the Team Where to go, what to do, what to see ‘Cyprus: Explore. Dream. Discover’, is an exclusive publication of Columbia Hotels & Resorts, informed - in parts - by Time Out Cyprus Visitors Guide. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, kindly note that details are subject to change. Please feel free to take this guide home with you, as a token of your time at Columbia and your visit to Cyprus! Pissouri Bay ...our charming hideaway culpted into the landscape of Pissouri, Columbia Hotels & Resorts takes great pride in its home space, fi ercely respecting the full force of its natural beauty and charm. And our eagerness to be able to intimately Sacquaint our guests with the village and its surrounding area is palpable. Pissouri’s rolling, lush hills fuse with the sapphire, clear waters of the 2km-long, Blue Flag-honoured Bay – upon which Columbia Beach Resort is poised – making for a majestic sight to behold. Nestled into the mountain’s side is the village, alive with familial generations of different backgrounds and cultures. Quaint and intimate as it may be, Pissouri village’s administrative area is in fact the third largest in the Limassol district, with some 1,100 inhabitants. And as remote and secluded as the village is, it is still only a mere 30 minutes from both Limassol and Paphos, thus affording visitors the best of both worlds. -

The Wild Bees

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 924: 1–114 (2020)The wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) of the island of Cyprus 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.924.38328 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) of the island of Cyprus Androulla I. Varnava1, Stuart P.M. Roberts2, Denis Michez3, John S. Ascher4, Theodora Petanidou5, Stavroula Dimitriou5, Jelle Devalez5, Marilena Pittara1, Menelaos C. Stavrinides1 1 Department of Agricultural Sciences, Biotechnology and Food Science, Cyprus University of Technology, Arch. Kyprianos 30, Limassol, 3036, Cyprus 2 CAER, School of Agriculture, Policy and Development, The University of Reading, Reading, UK 3 Research Institute of Bioscience, Laboratory of Zoology, University of Mons, Place du parc 23, 7000 Mons, Belgium 4 Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, Singapore 5 Laboratory of Biogeography & Ecology, Department of Geo- graphy, University of the Aegean, 81100 Mytilene, Greece Corresponding author: Androulla I. Varnava ([email protected]); Menelaos C. Stavrinides ([email protected]) Academic editor: Michael S. Engel | Received 18 July 2019 | Accepted 25 November 2019 | Published 6 April 2020 http://zoobank.org/596BC426-C55A-40F5-9475-0934D8A19095 Citation: Varnava AI, Roberts SPM, Michez D, Ascher JS, Petanidou T, Dimitriou S, Devalez J, Pittara M, Stavrinides MC (2020) The wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) of the island of Cyprus. ZooKeys 924: 1–114.https://doi. org/10.3897/zookeys.924.38328 Abstract Cyprus, the third largest island in the Mediterranean, constitutes a biodiversity hotspot with high rates of plant endemism. The wild bees of the island were studied extensively by the native George Mavro- moustakis, a world-renowned bee taxonomist, who collected extensively on the island from 1916 to 1957 and summarised his results in a series of eight Cyprus-specific papers published from 1949 [“1948”] to 1957. -

Mfi Id Name Address Postal City Head Office

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE CYPRUS Central Banks CY000001 Central Bank of Cyprus 80, Tzon Kennenty Avenue 1076 Nicosia Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions CY130001 Allied Bank SAL 276, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Allied Bank SAL CY110001 Alpha Bank Limited 1, Prodromou Street 1095 Nicosia CY130002 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY120001 Arab Bank plc 1, Santaroza Avenue 1075 Nicosia JO Arab Bank plc CY130003 Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA 23, Olympion Street 3035 Limassol JO Arab Jordan Investment Bank SA CY130006 Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL 135, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3021 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut and the Arab Countries SAL CY130032 Bank of Beirut SAL 6, Griva Digeni Street 3106 Limassol LB Bank of Beirut SAL CY110002 Bank of Cyprus Ltd 51, Stasinou Street, Strovolos 2002 Nicosia CY130007 Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL 227, Archiepiskopou Makariou III Avenue 3105 Limassol LB Banque Européenne pour le Moyen - Orient SAL CY130009 Banque SBA 8C, Tzon Kennenty Street 3106 Limassol FR Banque SBA CY130010 Barclays Bank plc 88, Digeni Akrita Avenue 1061 Nicosia GB Barclays Bank plc CY130011 BLOM Bank SAL 26, Vyronos Street 3105 Limassol LB BLOM Bank SAL CY130033 BNP Paribas Cyprus Ltd 319, 28 Oktovriou Street 3105 Limassol CY130012 Byblos Bank SAL 1, Archiepiskopou Kyprianou Street 3036 Limassol LB Byblos Bank SAL CY151414 Co-operative Building Society of Civil Servants Ltd 34, Dimostheni Severi Street 1080 Nicosia -

University of Southampton Humanities Archaeology the Changing

University of Southampton Humanities Archaeology The Changing Maritime Landscape of the Akrotiri Peninsula (1650 BC – AD 650) By Annabel Crawford This Dissertation is submitted in part-fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September, 2016 Student Number: 27847284 ii Abstract The purpose of this study is to assess the changes in the geomorphology and archaeology of the Akrotiri peninsula during antiquity. By pulling together results from relevant investigations, I was able to assess the current state of knowledge, produce new hypotheses and offer recommendations for future research. This is the first time the geology and archaeology of the entire peninsula has been considered at all, let alone together, but the current interdisciplinary approach at Dreamer’s Bay and other locations across Cyprus paves the way for similar investigations at sites on the peninsula. Before that can happen, a summary of knowledge must be created from which to move forward. Research determined that interdisciplinary approaches had rarely been taken, although geological and archaeological material did exist separately, and in some cases overlapped with each other. The visibility of maritime activity increased throughout the study period, reflecting the general increase in the activity itself. A shift from the archaeologically ephemeral proto-harbours to engineered harbours occurred, although these proto-harbours still likely existed in areas of localised or smaller-scale activity. The settlements around which maritime activity and culture existed also grew across the periods despite occasional troughs, such as that which occurred at the end of the Late Cypriot period. The geological changes during this period were determined not to be as straightforward as the formation of the peninsula. -

Rapid Antigen Testing for Employees and the General Population Is In

Rapid antigen testing for employees and the general population is in progress – Testing units According to the decree in force, employees in businesses and other professional sectors who are returning to work on 8 February, are obliged to undergo an antigen rapid test. In this context, the Ministry of Health’s program of free screening with rapid antigen test continues, in order to ensure a smooth and safe re-opening of businesses/sectors. Based on the above and to make the screening possible for everyone returning to their work place, the employees are grouped alphabetically according to their surname, as follows: Day/Date Surname – Greek Surname – Latin alphabet alphabet Friday, 5 February Μ – Ο N – R Saturday, 6 Π – Σ S – V February Sunday, 7 Τ – Ω W – Z February Employees are encouraged to adhere to the above alphabetical grouping, so that the program will be carried out in an organized manner without overcrowding or inconvenience. The employees with a surname Α – Λ (Greek alphabet) and A - M (Latin alphabet) who have not proceeded for testing yet, are asked to undergo a test in the following days, since a negative rapid test outcome constitutes a requirement for returning to work. The testing program for employees will be carried out at the same time as the testing program for the general population. In order to better serve all citizens, 56 testing units are operating in all Districts, with extended operating hours for the period 5-7 February, as follows: Operating District Location of testing units hours Agios Ioannis Eleimon Church, 8.30 a.m. -

B52 - Apartments in Limassol Suburb (Erimi) - Resale Property

B52 - Apartments in Limassol suburb (Erimi) - resale property Status: Project delivered Location: Erimi, the Western suburb of Limassol, 10-minute drive from the city The housing estate comprising apartments is located in Erimi – a popular suburb of Limassol (within 10 minutes drive westwards of the city). The complex is very comfortable with all the modern conveniences. It has a large common swimming pool and sports grounds. A well-groomed landscape design park circles the buildings. Erimi (by the exertions of the vigorous mayor) is famous for its trendy and immaculate outlook in Cyprus. There are fountains and fancy sculptures in the centre of the spot. One-way streets have fine stone paving. Erimi is home to the Cyprus Museum of Wine. Orthodox Church is close at hand. But Cypriots are devoutly religious folk. They consider it improper for only one church to be found in the vicinity of such a well-known place. Therefore construction of a new great temple is under way in Erimi. Living in Erimi is likely to catch the fancy of totally different people. A beautiful Kourion beach is in 5 minutes drive. Strong breezes in combination with shallow water originate waves. Wallowing in them is a great fun for both kids and adults (the fun is perfectly safe at that as it is only 0.5-1.5 meters deep there). One will find first-rate restaurants and fish taverns on the beach too. Lovers of the antique may also freely enjoy those places. A huge hill overhangs the above beach. It hosts excavations of an ancient Greek and Roman town Kourion, probably the most large-scale and interesting excavations throughout Cyprus. -

40 Years Hashing in the Bundu

On! � l�uuwu ����WJwu�U(W �uuuu ���� !OTI[il]�W�UU�@JUU}j WJ� �����uu� �uu �w��[W� ��®li ®rul� �ml ���� ���®� ��rnJ®W�� Fellow Hashers! I am very honoured to find myself as On Pres on this special occasion. d I am the 42" Epi Hasher to hold this appointment and I am very aware of the hard work my predecessors have put in over the years to maintain the sporting spirit of our Hash. Many thousands of Hashers have passed through our RVs and enjoyed the company and the banter, and to those Epi Exiles wherever you are now, may I repeat that there is always a welcome and a cold beer for you here on Tuesday afternoons! I would like to thank everyone involved with the organisation of the programme for our Anniversary celebrations, and to wish you all a great weekend's hashing and please enjoy the entertainment. On On ! Peter Viney 1 th November 2007 1 In the Year of Our Lord Nineteen Hundred and Thirty Seven a group of rubber planters working in Malaya decided that, in order to preserve their sanity, they would get together once a week in their string vests, long shorts and plimsolls to go for a run around the plantation before collapsing outside the Selangor Club where they would have a few beers and a meal. The Selangor Club was known locally as the 'Hash House' because of the slang name of the food served there, and the sturdy group of runners were dubbed 'Harriers'. If you believe all of the above you are halfway to becoming a Hasher! Anyhow, since that first auspicious occasion, chapters of the Hash House Harriers formed in all parts of the world from Norway to New Zealand, and from Australia to America there are hundreds of clubs that meet weekly to run, eat, drink and generally enjoy themselves away from the usual run of the mill activities. -

POCA 2014 Abstracts

14th Meeting of Postgraduate Cypriot Archaeology THE MANY FACE(T)S OF CYPRUS Abstracts Caterina Scirè Calabrisotto (Florence) Palaeodietary Research in Cypriot Prehistoric Contexts: Methodology and Potentialities. A Case Study for Middle Bronze Age Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou Different models and strategies of food acquisition, production and consumption can reveal different technological and cultural strategies within the life of a community trough time, thus hinting at its social organization. Within this context, the importance of a palaeodietary research ranges far beyond the mere reconstruction of past human diet, providing useful data concerning both human impacts on the environment and the cultural behavior of a population, such as food supply and preparation, possible socio-economical and religious differences, possible trading among different communities. With reference to Prehistoric and Protohistoric Cyprus, notwithstanding different contributions to explain the patterns of development of the village-based communities towards more complex entities, palaeodietary studies are still lacking in the current literature. Given its significance, selected key-sites, pertaining to the period from the Late Chalcolithic to the beginning of Late Bronze Age, have been included into a palaeodietary research project intended to reconstruct Recent Prehistory diet in Cyprus. In particular, the focus will be drawn upon two main transitional horizons: the Philia facies at the very beginning of the Early Bronze Age, as well as the transition from the Middle to Late Bronze Age. With reference to the second one, the site of Erimi-Laonin tou porakou is discussed here. The Middle Bronze Age settlement is indeed located in a strategic position, with easy access both to marine and terrestrial resources, thus representing an interesting case of investigation in terms of food strategies and resource supplies. -

The Wild Bees

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys $$: @–@ (20##)The wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) of the island of Cyprus 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.@@.38328 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) of the island of Cyprus Androulla I. Varnava1, Stuart P.M. Roberts2, Denis Michez3, John S. Ascher4, Theodora Petanidou5, Stavroula Dimitriou5, Jelle Devalez5, Marilena Pittara1, Menelaos C. Stavrinides1 1 Department of Agricultural Sciences, Biotechnology and Food Science, Cyprus University of Technology, Arch. Kyprianos 30, Limassol, 3036, Cyprus 2 CAER, School of Agriculture, Policy and Development, The University of Reading, Reading, UK 3 Research Institute of Bioscience, Laboratory of Zoology, University of Mons, Place du parc 23, 7000 Mons, Belgium 4 Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, Singapore 5 Laboratory of Biogeography & Ecology, Department of Geo- graphy, University of the Aegean, 81100 Mytilene, Greece Corresponding author: Androulla I. Varnava ([email protected]); Menelaos C. Stavrinides ([email protected]) Academic editor: Michael S. Engel | Received 18 July 2019 | Accepted 25 November 2019 | Published @@ @@@@ 20## http://zoobank.org/ Citation: Varnava AI, Roberts SPM, Michez D, Ascher JS, Petanidou T, Dimitriou S, Devalez J, Pittara M, Stavrinides MC (20##) The wild bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) of the island of Cyprus. ZooKeys @@: @–@.https://doi. org/10.3897/zookeys.@@.38328 Abstract Cyprus, the third largest island in the Mediterranean, constitutes a biodiversity hotspot with high rates of plant endemism. The wild bees of the island were studied extensively by the native George Mavro- moustakis, a world-renowned bee taxonomist, who collected extensively on the island from 1916 to 1957 and summarised his results in a series of eight Cyprus-specific papers published from 1949 [“1948”] to 1957. -

475 Erimi-Laonin Tou Porakou (Limassol, Cyprus

ERIMI-LAONIN TOU PORAKOU (LIMASSOL, CYPRUS): RADIOCARBON ANALYSES OF THE BRONZE AGE CEMETERY AND WORKSHOP COMPLEX C Scirè Calabrisotto1,2 • M E Fedi3 • L Caforio3,4 • L Bombardieri1 ABSTRACT. The site area of Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou (Limassol, Cyprus) has been surveyed and systematically exca- vated since 2007 as a joint research project of the University of Florence and the Department of Antiquities of Cyprus. A focused investigation was dedicated to analyzing funerary evidence from the southern Cemetery (Area E), where 7 single- chamber graves were excavated. The offering goods assemblages from the burials point to a general date ranging from Early to Late Bronze Age I, and draw a sequence of use that is contemporary to the stratigraphic deposits from the top mound Work- shop Complex (Area A). During the 2010 field season, charcoal samples from the Workshop Complex and bone samples from the skeleton remains of 2 burials (tombs 228, 230) were opportunely taken for radiocarbon analyses. 14C dating was per- formed at the AMS-IBA Tandetron accelerator of the INFN-LABEC Laboratory in Florence. This paper will discuss the results of the 14C analyses and compare them with the archaeological evidence in order to outline a chronological sequence for the settlement and cemetery areas at Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou, thus collecting further data on the development and pat- tern of occupation of the Early to Late Cypriote period in the Kourion area. INTRODUCTION Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou is located in southern Cyprus, in the Limassol District, lying on a high plateau on the eastern slope of the Kouris River, facing the modern Kouris Dam to the south (Cadas- tral Sheet LIII/46, Plots 331–336, 384; 344243N, 325523E), just on the border between the Ypsonas and Erimi villages (Figure 1a). -

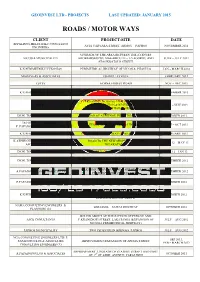

Complete List of ROADS / MOTOR WAYS

GEOINVEST LTD - PROJECTS LAST UPDATED: JANUARY 2015 ROADS / MOTOR WAYS CLIENT PROJECT-SITE DATE EFPALINOS MELETITIKI CONSULTING AYIA VARVARA STREET, ARMOU – PAPHOS NOVEMBER 2014 ENGINEERS UPGRADE OF THE AREA BETWEEN THE AVENUES NICOSIA MUNICIPALITY ARCHIERISKOPOU MAKARIOU III – EVAGOROU AND JUNE – JULY 2014 STASIKRATOUS STREET K/X PERIMETRIKI LEFKOSIAS PERIMETRICAL HIGHWAY OF NICOSIA, PHASE D2 JAN – MARCH 2014 MARAVEAS & ASSOCIATES TSERIOU AVENUE FEBRUARY 2014 CSP JV ACHNA FOREST ROAD NOV – DEC 2013 PERIMETRICAL HIGHWAY OF NICOSIA, ADDITIONAL K/X PERIMETRIKI LEFKOSIAS NOVEMBER 2013 RESEARCH PERGAMOS CROSSING POINT - STORM DRAIN CSP JV CONSTRUCTION & RESURFACING, OCT – NOV 2013 DHEKELIA BRITISH BASES AREA DION. TOUMAZIS & ASSOCIATES ROAD OF ATHIENOU INDUSTRIAL AREA, OCTOBER 2013 IACOVOU – CYBARCO JV, ZYGOS BRIDGE, ALASSA – LIMASSOL SEPT – OCT 2013 P. PAPADOPOULOS & ASSOCIATES K/X PERIMETRIKI LEFKOSIAS PERIMETRICAL HIGHWAY OF NICOSIA, PHASE E FEBRUARY 2013 K.ATHIENITES CONSTRUCTIONS LTD / ROAD TO THE NEW SHOPPING CENTER NOV 12 – MAY 13 ASCE CONSULTANTS IN LAKATAMIA DION. TOUMAZIS & ASSOCIATES KOUKLIA COMMUNITY, PHASE A & B DEC 12 – JAN 13 ROAD NETWORK OF ATHIENOU INDUSTRIAL AREA, DION. TOUMAZIS & ASSOCIATES DECEMBER 2012 PRELIMINARY STAGE MAKARIOU III AVENUE AND PART OF LIMASSOL A.PAPADOPOULOS & ASSOCIATES DECEMBER 2012 HIGHWAY, PERA CHORIO-NISOU VIADUCTS IN THE INDUSTRIAL AREA OF MESOGIS – P.PAPADOPOULOS & ASSOCIATES OCTOBER 2012 TREMYTHOUSAS, PAPHOS PEDIAIOS BRIDGE OF NICOSIA PERIMETRICAL HIGHWAY K/X PERIMETRIKI LEFKOSIAS (ROUND ABOUT OF DALI INDUSTRIAL AREA AND OCTOBER 2012 LIMASSOL ROUND ABOUT) NAMA CONSULTING ENGINEERS & LIMASSOL – SAITAS HIGHWAY OCTOBER 2012 PLANNERS SA ROUND ABOUT AT THE JUCTION OF PEFKOU AND ASCE CONULTANTS Y.KRANIDIOTI STREET, LAKATAMIA (EXPANSION OF JULY – AUG 2012 NICOSIA PERIMETRICAL HIGHWAY) PAPHOS MUNICIPALITY TWO PEDESTRIAN BRIDGES, PAPHOS JULY – AUG 2012 NGA CONSULTING ENGINEERS LTD/ P.