POTTERY ANALYSIS of Kuntasl CHAPTEH IV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

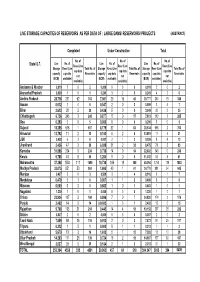

Live Storage Capacities of Reservoirs As Per Data of : Large Dams/ Reservoirs/ Projects (Abstract)

LIVE STORAGE CAPACITIES OF RESERVOIRS AS PER DATA OF : LARGE DAMS/ RESERVOIRS/ PROJECTS (ABSTRACT) Completed Under Construction Total No. of No. of No. of Live No. of Live No. of Live No. of State/ U.T. Resv (Live Resv (Live Resv (Live Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of cap data cap data cap data capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs not not not (BCM) available) (BCM) available) (BCM) available) available) available) available) Andaman & Nicobar 0.019 20 2 0.000 00 0 0.019 20 2 Arunachal Pradesh 0.000 10 1 0.241 32 5 0.241 42 6 Andhra Pradesh 28.716 251 62 313 7.061 29 16 45 35.777 280 78 358 Assam 0.012 14 5 0.547 20 2 0.559 34 7 Bihar 2.613 28 2 30 0.436 50 5 3.049 33 2 35 Chhattisgarh 6.736 245 3 248 0.877 17 0 17 7.613 262 3 265 Goa 0.290 50 5 0.000 00 0 0.290 50 5 Gujarat 18.355 616 1 617 8.179 82 1 83 26.534 698 2 700 Himachal 13.792 11 2 13 0.100 62 8 13.891 17 4 21 J&K 0.028 63 9 0.001 21 3 0.029 84 12 Jharkhand 2.436 47 3 50 6.039 31 2 33 8.475 78 5 83 Karnatka 31.896 234 0 234 0.736 14 0 14 32.632 248 0 248 Kerala 9.768 48 8 56 1.264 50 5 11.032 53 8 61 Maharashtra 37.358 1584 111 1695 10.736 169 19 188 48.094 1753 130 1883 Madhya Pradesh 33.075 851 53 904 1.695 40 1 41 34.770 891 54 945 Manipur 0.407 30 3 8.509 31 4 8.916 61 7 Meghalaya 0.479 51 6 0.007 11 2 0.486 62 8 Mizoram 0.000 00 0 0.663 10 1 0.663 10 1 Nagaland 1.220 10 1 0.000 00 0 1.220 10 1 Orissa 23.934 167 2 169 0.896 70 7 24.830 174 2 176 Punjab 2.402 14 -

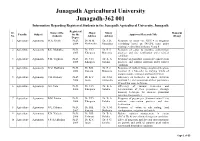

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

(PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat

ROADS AND BUILDINGS DEPARTMENT (PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) FOR GUJARAT RURAL ROADS (MMGSY) PROJECT Under AIIB Loan Assistance May 2017 LEA Associates South Asia Pvt. Ltd., India Roads & Buildings Department (Panchayat), Environmental and Social Impact Government of Gujarat Assessment (ESIA) Report Table of Content 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 MUKHYA MANTRI GRAM SADAK YOJANA ................................................................ 1 1.3 SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT: GUJARAT .................................... 3 1.3.1 Population Profile ........................................................................................ 5 1.3.2 Social Characteristics ................................................................................... 5 1.3.3 Distribution of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population ................. 5 1.3.4 Notified Tribes in Gujarat ............................................................................ 5 1.3.5 Primitive Tribal Groups ............................................................................... 6 1.3.6 Agriculture Base .......................................................................................... 6 1.3.7 Land use Pattern in Gujarat ......................................................................... -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Ahmedabad Sector

Office of the Chief Commissioner of Central Excise, Ahmedabad Zone, 7th Floor, Central Excise Bhavan, Near Polytechn_c, Ambavadi, Ahmedabad — 380 015 Email : ccuahmedabad gmail.com Fax: (079) 26303607 Tel.: (079) 26303612 Establishment Order No. 27 / 2014 Dated 13th June, 2014 Sub : Annual General Transfer — J014 in the grade of Inspector — Regarding The following Inspectors of Customs Gujarat Zone are hereby transferred and posted to Central Excise, Ahmedabad Ione with immediate effect and until further orders. Sr. Name of the Officer FroM To No. S/Shri 01 Shri Neeraj Singh Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector 02 Shri Manish Kumar Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector Singh 03 Shri Rupesh Kumar Customs, Ahm:xlabad Ahmedabad Sector Suman 04 Shri Rajendra Singh Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector 05 Shri Saurabh Prakash Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector 06 Shri Narendra Kumar Customs, Ah dabad Ahmedabad Sector Rai 07 Shri Nirmal Kumar Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector Jha 08 Shri Suraj Prakash Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector 09 Shri Sarvesh Kumar Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector Singh 10 Shri Jay Kumar Customs, Ahrr edabad Ahmedabad Sector Bishwas 11 Shri Narendra Kumar Customs, A edabad Ahmedabad Sector Meena 12 Shri Rakesh Devathia Customs, Ahniedabad Ahmedabad Sector 13 Shri Premraj Meena Customs, Ahrnedabad Ahmedabad Sector 14 Shri Navin Kumar Customs, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad Sector 15 Shri K.J. Acharya Customs, Kandla Ahmedabad Sector 16 Shri M.J. Shulda Customs, Kandla Ahmedabad Sector 17 Shri P.C. Dave Customs, Kandla Ahmedabad Sector 18 Shri L.C. Bodat Customs, Kandla Ahmedabad Sector 19 Shri B.S. Bhagora Customs, Karklla Ahmedabad Sector 20 Shri F.S. Shaikh Customs, Ka4dla Ahmedabad Sector ' Sr. -

DENA BANK.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE South ANDAMAN Andaman,Village &P.O AND -BambooFlat(Near bambooflat NICOBAR Rehmania Masjid) BAMBOO @denaban ISLAND ANDAMAN Bambooflat ,Andaman-744103 FLAT BKDN0911514 k.co.in 03192-2521512 non-MICR Port Blair,Village &P.O- ANDAMAN Garacharma(Near AND Susan garacharm NICOBAR Roses,Opp.PHC)Port GARACHAR a@denaba ISLAND ANDAMAN Garacharma Blair-744103 AMA BKDN0911513 nk.co.in (03192)252050 non-MICR Boddapalem, Boddapalem Village, Anandapuram Mandal, ANDHRA Vishakapatnam ANANTAPU 888642344 PRADESH ANANTAPUR BODDAPALEM District.PIN 531163 R BKDN0631686 7 D.NO. 9/246, DMM GATE ANDHRA ROAD,GUNTAKAL – 08552- guntak@denaba PRADESH ANANTAPUR GUNTAKAL 515801 GUNTAKAL BKDN0611479 220552 nk.co.in 515018302 Door No. 18 slash 991 and 992, Prakasam ANDHRA High Road,Chittoor 888642344 PRADESH CHITTOOR Chittoor 517001, Chittoor Dist CHITTOOR BKDN0631683 2 ANDHRA 66, G.CAR STREET, 0877- TIRUPA@DENA PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATHI TIRUPATHI - 517 501 TIRUPATI BKDN0610604 2220146 BANK.CO.IN 25-6-35, OPP LALITA PHARMA,GANJAMVA ANDHRA EAST RI STREET,ANDHRA 939474722 KAKINA@DENA PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA PRADESH-533001, KAKINADA BKDN0611302 2 BANK.CO.IN 1ST FLOOR, DOOR- 46-12-21-B, TTD ROAD, DANVAIPET, RAJAHMUNDR ANDHRA EAST RAJAMUNDRY- RAJAHMUN 0883- Y@DENABANK. PRADESH GODAVARI RAJAHMUNDRY 533103 DRY BKDN0611174 2433866 CO.IN D.NO. 4-322, GAIGOLUPADU CENTER,SARPAVAR AM ROAD,RAMANAYYA ANDHRA EAST RAMANAYYAPE PETA,KAKINADA- 0884- ramanai@denab PRADESH GODAVARI TA 533005 KAKINADA BKDN0611480 2355455 ank.co.in 533018003 D.NO.7-18, CHOWTRA CENTRE,GABBITAVA RI STREET, HERO HONDA SHOWROOM LINE, ANDHRA CHILAKALURIPE CHILAKALURIPET – CHILAKALU 08647- chilak@denaban PRADESH GUNTUR TA 522616, RIPET BKDN0611460 258444 k.co.in 522018402 23/5/34 SHIVAJI BLDG., PATNAM 0836- ANDHRA BAZAR, P.B. -

'A Study of Tourism in Gujarat: a Geographical Perspective'

‘A Study of Tourism in Gujarat: A Geographical Perspective” CHAPTER-2 GEOGRAPHICAL PROFILE OF THE STUDY AREA ‘A Study of Tourism in Gujarat: A Geographical Perspective’ 2.1 GUJARAT : AN INTRODUCTION Gujarat has a long historical and cultural tradition dating back to the days of the Harappan civilization established by relics found at Lothal(Figure-1).It is also called as the “Jewel of the West”, is the westernmost state of India(Figure-2). The name “Gujarat” itself suggests that it is the land of Gurjars, which derives its name from ‘Gujaratta’ or ‘Gujaratra’ that is the land protected by or ruled by Gurjars. Gurjars were a migrant tribe who came to India in the wake of the invading Huna’s in the 5th century. The History of Gujarat dates back to 2000 BC. Some derive it from ‘Gurjar-Rashtra’ that is the country inhabited by Gurjars. Al-Beruni has referred to this region as ‘Gujratt’. According to N.B. Divetia the original name of the state was Gujarat & the above- mentioned name are the Prakrit& Sanskrit forms respectively. The name GUJARAT, which is formed by adding suffix ‘AT’ to the word ‘Gurjar’ as in the case of Vakilat etc. There are many opinions regarding the arrivals of Gurjars, two of them are, according to an old clan, they inhabited the area during the Mahabharat period and another opined that they belonged to Central Asia and came to India during the first century. The Gurjars passed through the Punjab and settled in some parts of Western India, which came to be known as Gujarat.Gujarat was also inhabited by the citizens of the Indus Valley and Harappan civilizations. -

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat Tannen Neil Lincoln ISBN 978-81-7791-236-4 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. Working Paper Series Editor: Marchang Reimeingam THE POLITICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MODERN -

Provisioning Drinking Water in Gujarat's Tribal Areas: an Assessment

Working Paper No. 225 Provisioning Drinking Water in Gujarat’s Tribal Areas: An Assessment Keshab Das February 2015 Gujarat Institute of Development Research Gota, Ahmedabad 380 060 Abstracts of all GIDR Working Papers are available on the Institute’s website. Working Paper No 121 onwards can be downloaded from the site. All rights are reserved. This publication may be used with proper citation and due acknowledgement to the author(s) and the Gujarat Institute of Development Research, Ahmedabad. © Gujarat Institute of Development Research First Published February 2015 ISBN 81-89023-83-7 Price Rs. 100.00 Abstract Drawing upon both intensive and extensive field research, this paper assesses state provisioning of drinking water in 48 designated tribal talukas of 12 districts in the west Indian state of Gujarat, through the much-publicized Vanbandhu Kalyan Yojana (VKY) of the Tribal Development Department (TDD). Absence of comprehensive and accessible basic data on the programme remained a major constraint in following up implementation and ensuring corrective measures en route. Despite claims of transparency and efficiency, it was near impossible to obtain village wise and scheme wise financial information as the TDD, the originator of the VKY, did not possess relevant data on these. This lacunae was compounded by the overlapping of interventions and difficulty in rendering the relevant agency responsive. The programme’s excessive dependence on groundwater, even in high-rainfall areas in south Gujarat, for drinking water purposes posed serious challenges in a state suffering steady decline in groundwater tables in several regions. Governance deficit was obvious at the village level where participation in Gram Sabhas was often low. -

Vulture Status of Gujarat of the Nine Species of Vultures Recorded In

Vulture Status of Gujarat Of the nine species of vultures recorded in India, seven species i.e. White-rumped Vulture, Long-billed Vulture, Eurasian Griffon, Egyptian Vulture, Red-headed Vulture, Cinereous Vulture and Himalayan Griffon. Of these seven species, four species White-rumped Vulture, Long-billed Vulture, Red-headed Vulture and Egyptian Vulture are regularly sighted in Gujarat. Currently, the vulture Population estimation was done by GEER foundation. A total of 999 vultures of four species were recorded during May, 2016 estimation. Of these, 843 individuals were Gyps vulture (458 White-rumped Vultures and 385 Long-billed Vultures), 24 Red-headed Vultures and 132 Egyptian Vultures. While during the previous state wise estimation in May 2012, a total of 1,037 vulture were recorded which included 938 Gyps vultures (577 White-rumped Vultures & 361 Long-billed Vultures), 8 Red-headed Vultures and 97 Egyptian Vultures. Of the four species of vultures covered under current population estimation, three species viz. Red-headed Vulture, Egyptian Vulture and Long-billed Vulture, have shown population increase by 300%, 36.1% and 6.65%, respectively as compared with the population estimation 2012. Among various regions of the State, Saurashtra region support the highest population of the four species of vultures population of the four species of vultures (n=458, i.e., 45.84% of total population) followed by North Gujarat (n=203, i.e., 20.32% of total population). Central Gujarat and South Gujarat support 157 (15.71% of total population) and 109 vultures (10.91% of total population) and 109 vultures (10.91% of total population0 respectively, whereas Kachchh region recorded the lowest population of vultures (n=72) during the 2016 estimation.Saurashtra region support the highest population of Gyps vultures (n=430; 67.11% of the total population) population is concerned. -

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT

The Decline of Harappan Civilization K.N.DIKSHIT EBSTRACT As pointed out by N. G. Majumdar in 1934, a late phase of lndus civilization is illustrated by pottery discovered at the upper levels of Jhukar and Mohenjo-daro. However, it was the excavation at Rangpur which revealed in stratification a general decline in the prosperity of the Harappan culture. The cultural gamut of the nuclear region of the lndus-Sarasvati divide, when compared internally, revealed regional variations conforming to devolutionary tendencies especially in the peripheral region of north and western lndia. A large number of sites, now loosely termed as 'Late Harappan/Post-urban', have been discovered. These sites, which formed the disrupted terminal phases of the culture, lost their status as Harappan. They no doubt yielded distinctive Harappan pottery, antiquities and remnants of some architectural forms, but neither town planning nor any economic and cultural nucleus. The script also disappeared. ln this paper, an attempt is made with the survey of some of these excavated sites and other exploratory field-data noticed in the lndo-Pak subcontinent, to understand the complex issue.of Harappan decline and its legacy. CONTENTS l.INTRODUCTION 2. FIELD DATA A. Punjab i. Ropar ii. Bara iii. Dher Majra iv. Sanghol v. Katpalon vi. Nagar vii. Dadheri viii. Rohira B. Jammu and Kashmir i. Manda C. Haryana i. Mitathal ii. Daulatpur iii. Bhagwanpura iv. Mirzapur v. Karsola vi. Muhammad Nagar D. Delhi i. Bhorgarh 125 ANCiENT INDlA,NEW SERIES,NO.1 E.Western Uttar Pradesh i.Hulas il.Alamgirpur ili.Bargaon iv.Mandi v Arnbkheri v:.Bahadarabad F.Guiarat i.Rangpur †|.Desalpur ili.Dhola宙 ra iv Kanmer v.」 uni Kuran vi.Ratanpura G.Maharashtra i.Daimabad 3.EV:DENCE OF RICE 4.BURIAL PRACTiCES 5.DiSCUSS10N 6.CLASSiFiCAT10N AND CHRONOLOGY 7.DATA FROM PAKISTAN 8.BACTRIA―MARGIANAARCHAEOLOGICAL COMPLEX AND LATE HARAPPANS 9.THE LEGACY 10.CONCLUS10N ・ I.