5The Infinitive in the Writing of Czech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional

Traditional Grammar Review Page 1 of 15 TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional grammar recognizes eight parts of speech: Part of Definition Example Speech noun A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. John bought the book. verb A verb is a word which expresses action or state of being. Ralph hit the ball hard. Janice is pretty. adjective An adjective describes or modifies a noun. The big, red barn burned down yesterday. adverb An adverb describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or He quickly left the another adverb. room. She fell down hard. pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. She picked someone up today conjunction A conjunction connects words or groups of words. Bob and Jerry are going. Either Sam or I will win. preposition A preposition is a word that introduces a phrase showing a The dog with the relation between the noun or pronoun in the phrase and shaggy coat some other word in the sentence. He went past the gate. He gave the book to her. interjection An interjection is a word that expresses strong feeling. Wow! Gee! Whew! (and other four letter words.) Traditional Grammar Review Page 2 of 15 II. Phrases A phrase is a group of related words that does not contain a subject and a verb in combination. Generally, a phrase is used in the sentence as a single part of speech. In this section we will be concerned with prepositional phrases, gerund phrases, participial phrases, and infinitive phrases. Prepositional Phrases The preposition is a single (usually small) word or a cluster of words that show relationship between the object of the preposition and some other word in the sentence. -

1St Rule: FANBOYS and Compound Sentences FANBOYS Is a Mnemonic Device, Which Stands for the Coordinating Conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, and So

1st Rule: FANBOYS and Compound Sentences FANBOYS is a mnemonic device, which stands for the coordinating conjunctions: For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, and So. These words, when used to connect two independent clauses (two complete thoughts), must be preceded by a comma. A sentence is a complete thought, consisting of a Subject and a Verb. Conjunctions should not be confused with conjunctive adverbs, such as However, Therefore, and Moreover or with conjunctions, such as Because. 2nd Rule: Introductory Bits When using an introductory word, phrase, or clause to begin a sentence, it is important to place a comma between the introduction and the main sentence. The introduction is not a complete thought on its own; it simply introduces the main clause. This lets the reader know that the “meat” of the sentence is what follows the comma. You should be able to remove the part which comes before the comma and still have a complete thought. Examples: Generally, John is opposed to overt acts of affection. However, Lucy inspires him to be kind. If the hamster is launched fifty feet, there is too much pressure in the cannon. Although the previous sentence has little to do with John and Lucy, it is a good example of how to use commas with introductory clauses. 3rd Rule: Separating Items in a Series Commas belong between each item in a list. However, in a series of three items, the comma between the second and third item and the conjunction (generally and or or) is optional, whereas in a list of four items, the comma is necessary. -

Conjunction Junction WHAT’S THEIR FUNCTION? What Are Conjunctions, Anyway?

Conjunction Junction WHAT’S THEIR FUNCTION? What are conjunctions, anyway? A conjunction is a word used to connect clauses or sentences or to coordinate words in the same clause. What kinds of conjunctions are there? • Coordinating conjunctions (=) • FANBOYS • Correlating Conjunctions • Both…and, either…or, neither…nor, whether…or, not only…but also • Subordinating Conjunctions (< ) • After, although, as, because, before, how, if, since, than, that, though, unless, until, what (whatever), when (whenever), where (wherever), whereas, whether, which (whichever), while, who (whom, whomever), whose • Conjunctive Adverb () • Accordingly, however, nonetheless, also, indeed, otherwise, besides, instead, similarly, consequently, likewise, still, conversely, meanwhile, subsequently, finally, moreover, then, furthermore, nevertheless, therefore, hence, next, thus Coordinating Conjunctions • Coordinating Conjunctions are used to connect two complete sentences(independent clauses) and coordinating words and phrases. • All coordinating conjunctions MUST be preceded by a comma if connecting two independent clauses. Coordinating Conjunctions at Work • Miss Smidgin was courteous but cool. (coordinating adjectives) • The next five minutes will determine whether we win or lose. (coordinating verbs) • This chimp is crazy about peanuts but also about strawberries. (coordinating prepositional phrases) • He once lived in mansions, yet now he is living in an empty box. (coordinating independent clauses) • You probably won’t have any trouble spotting him, for he weighs almost three hundred pounds. • She didn’t offer help, nor did she offer any excuse for her laziness. • I wanted to live closer to Nature, so I built myself a cabin in the swamps of Louisiana. Correlating Conjunctions Correlating Conjunctions connect two equal phrases. Correlating Conjunctions at Work • In the fall, Phillip will either start classes at the community college or join the navy. -

Using-Conjunctions.Pdf

GRAMMAR AND MECHANICS Using Conjunctions A conjunction is the part of speech used to join or link words, phrases, or clauses to each other. Conjunctions help to provide coherence to your writing by connecting elements between or within sentences and from one paragraph to the next in order to most effectively communicate your ideas to your reader. TYPES OF CONJUNCTIONS Coordinating conjunctions or coordinators (and, but, or, nor, so, for, yet) connect ideas of equal structure or function. The instructor was interesting and extremely knowledgeable about the subject. The play was entertaining but disappointing. I am a highly motivated and diligent worker, so I should be considered for the job. Correlative conjunctions come in pairs and function like coordinating conjunctions to connect equal elements. The most common correlative conjunctions are either . or, neither . nor, not only . but also, whether . or, and both . and. Either Miranda or Julia will fill the recently vacated position. Both the music and the lyrics were written by the same composer. Subordinating conjunctions or subordinators such as if, when, where, because, although, since, whether, and while introduce a subordinate or dependent clause that is usually attached to an independent clause and signal the relationship between the clauses. If the director is unavailable, I will speak with her assistant. When the speaker finished, the audience responded with tremendous applause. As a general rule, if a subordinating or dependent clause precedes the independent clause, use a comma to separate the two clauses. Since the secretary was unable to find the file (subordinating or dependent clause), the meeting was cancelled (independent clause). -

Constituency Tests Ling201, Apr

Constituency Tests Ling201, Apr. 14 The following tests help us to determine whether a string of words forms a constituent. Key: Constituents are underlined. Non-constituents are wavy-lined. Warning: Not all tests will work for all constituent types! Fragment Answers Only a constituent can answer a question, while retaining the meaning of the original sentence. That ismy rother. → !: "ho#s that$ A: &y rother. 'e is making a mess. → !: "hat#s he doing$ A: &aking a mess. The keys are on the ta le. → !: "here are the keys? A: On the ta le. I want two of those apples. → !: 'ow many apples do you want$ A: *)wo of. 'e#s preserving in wa* the earwigs I gave him. → !: "hat#s he doing with the earwigs? A: *+reserving in wa*. I gave the dog the keys. → !: "hat did you do with the keys? A: *,ave the dog. Coordination Only constituents -of the same type) can e coordinated using conjunction words like and, or, and but. 'er friends from +eru went to the show. → &ary and her friends from +eru went to the show. "e peeled the potatoes. → "e peeled the potatoes and shucked the corn. /hould I go through the tunnel$ → /hould I go through the tunnel or over the ridge$ The doughnuts were full of 0elly. → The doughnuts were full of 0elly ut slightly disappointing. 'er friends from +eru went to the movies. → *'er friends from and two guys interested in +eru went1 "e peeled the potatoes. → *"e peeled the and washed the potatoes. /hould I go through the tunnel$ → */hould I go through or I go around the tunnel$ The doughnuts were full of 0elly. -

Phrasal Conjunction and Symmetric Predicates

.. '-~ ·... ]" '· MODERN STUDIES IN ENGLISH Readings in Transformational Grammar Edited by DAVID A. REIBEL " University of York SANFORD A. SCHANE Univertit1 of CJifornill. at San Diego . '~ I ~.' 1-" c c ! . ,' ' ." ':- ····- .. :', : ·.~:·· ,,,··· ""''·· l,_ '·• ;'. ,.41•, ' L ;.,_ ~ L~ -'1 Loft':-"! • ~~~ ..... <t ' l'lp: ~·~·,. ~. ''·""-~•· ', . .-.~; :: •, ~ ! :~,...~~ ~~X.::.~f-~,-~~:: ·l' ·~";j<iJ'-. :'ll!_:~t:::'""'~.,%ITPWt{:.f:~_?· ~~y}. ~~ E''-l~5 .I .·,, )~ :,. '. '0':, f' ·.·· . :,f ...... '112 ~- (204) Tryl1.1l4 ~tell me. (205} Do m8 o /arcr tm4 #I t/owtt. The intorlation contour for such sentences seems quite difl'erent from that asso-: ciated with C:OtVoined X-C-X. If that is so, such occurrences can be treated much like modal verbs, the and being classified as similar to infinitival to. Evidence for the oddity of this use, beyond the difference in intonation contour, is its un 10 systematic nature: (a) where affixes are required on the verb forms, this usage is ,,l. avoided (e.g. They try and get it,· but • He tries 411d get It; He tries to get it),· and I: (b) iteration is not uniformly allowable (e.g. Do me a favor and run and get It; Phrasal Conjunction but ?Run and do me a favor and get it.) 2. •• AND" AS AN JN'Il!NSIFIER. (xxvi) disallows the conjunction of identical constit and Symmetric Predicates uents, because (xxiv) does not mark them. However, we often find and between identical words and phrases without contrastive stress (e.g. We went around and around, She hit him and hit him.). Such repetitions have the effect of suggesting GEORGE LAKOFF and STANLEY PETERS continuous or repeated or increasing action~ They are not allowable on all constit uents conjoinable by (xxvi) (e.g. -

Constructions and Result: English Phrasal Verbs As Analysed in Construction Grammar

CONSTRUCTIONS AND RESULT: ENGLISH PHRASAL VERBS AS ANALYSED IN CONSTRUCTION GRAMMAR by ANNA L. OLSON A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Master of Arts in Linguistics, Analytical Stream We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard ............................................................................... Dr. Emma Pavey, PhD; Thesis Supervisor ................................................................................ Dr. Sean Allison, Ph.D.; Second Reader ................................................................................ Dr. David Weber, Ph.D.; External Examiner TRINITY WESTERN UNIVERSITY September 2013 © Anna L. Olson i Abstract This thesis explores the difference between separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs, focusing on finding a reason for the non-separable verbs’ lack of compatibility with the word order alternation which is present with the separable phrasal verbs. The analysis is formed from a synthesis of ideas based on the work of Bolinger (1971) and Gorlach (2004). A simplified version of Cognitive Construction Grammar is used to analyse and categorize the phrasal verb constructions. The results indicate that separable and non-separable transitive English phrasal verbs are similar but different constructions with specific syntactic reasons for the incompatibility of the word order alternation with the non-separable verbs. ii Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... -

A New Outlook of Complementizers

languages Article A New Outlook of Complementizers Ji Young Shim 1,* and Tabea Ihsane 2,3 1 Department of Linguistics, University of Geneva, 24 rue du Général-Dufour, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland 2 Department of English, University of Geneva, 24 rue du Général-Dufour, 1211 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 University Priority Research Program (URPP) Language and Space, University of Zurich, Freiestrasse 16, 8032 Zurich, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-22-379-7236 Academic Editor: Usha Lakshmanan Received: 28 February 2017; Accepted: 16 August 2017; Published: 4 September 2017 Abstract: This paper investigates clausal complements of factive and non-factive predicates in English, with particular focus on the distribution of overt and null that complementizers. Most studies on this topic assume that both overt and null that clauses have the same underlying structure and predict that these clauses show (nearly) the same syntactic distribution, contrary to fact: while the complementizer that is freely dropped in non-factive clausal complements, it is required in factive clausal complements by many native speakers of English. To account for several differences between factive and non-factive clausal complements, including the distribution of the overt and null complementizers, we propose that overt that clauses and null that clauses have different underlying structures responsible for their different syntactic behavior. Adopting Rizzi’s (1997) split CP (Complementizer Phrase) structure with two C heads, Force and Finiteness, we suggest that null that clauses are FinPs (Finiteness Phrases) under both factive and non-factive predicates, whereas overt that clauses have an extra functional layer above FinP, lexicalizing either the head Force under non-factive predicates or the light demonstrative head d under factive predicates. -

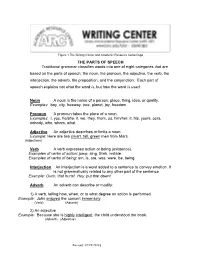

THE PARTS of SPEECH Traditional Grammar Classifies Words Into One

Figure 1 The Writing Center and Academic Resource Center logo THE PARTS OF SPEECH Traditional grammar classifies words into one of eight categories that are based on the parts of speech: the noun, the pronoun, the adjective, the verb, the interjection, the adverb, the preposition, and the conjunction. Each part of speech explains not what the word is, but how the word is used. Noun A noun is the name of a person, place, thing, idea, or quality. Examples: boy, city, freeway, tree, planet, joy, freedom Pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. Examples: I, you, he/she, it, we, they, them, us, him/her, it, his, yours, ours, nobody, who, whom, what Adjective An adjective describes or limits a noun. Example: Here are two smart, tall, green men from Mars. (Adjectives) Verb A verb expresses action or being (existence). Examples of verbs of action: jump, sing, think, imitate. Examples of verbs of being: am, is, are, was, were, be, being Interjection An interjection is a word added to a sentence to convey emotion. It is not grammatically related to any other part of the sentence. Example: Ouch, that hurts! Hey, put that down! Adverb An adverb can describe or modify: 1) A verb, telling how, when, or to what degree an action is performed. Example: John enjoyed the concert immensely. (Verb) (Adverb) 2) An adjective Example: Because she is highly intelligent, the child understood the book. (Adverb) (Adjective) Revised: 07/25/20181 3) Another adverb Example: The pedestrian ran across the street very rapidly. (Verb) (Adverb) (The adverb “rapidly” modifies the verb “ran,” and the adverb “very” modifies the adverb “rapidly.”) Preposition A word that shows the relation of a noun or pronoun to some other word in the sentence. -

Composing Cps: Evidence from Disjunction and Conjunction*

Proceedings of SALT 30: 000–000, 2020 Composing CPs: evidence from disjunction and conjunction* Itai Bassi Tatiana Bondarenko Massachusetts Institute of Technology Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract In this paper we compare CP disjunction to TP disjunction and CP con- junction to TP conjunction, and conclude that CPs and TPs do not have identical meanings (cf. similar observations reported in Szabolcsi 1997, 2016; Bjorkman 2013). We argue that this result is incompatible with the view that the CP layer of embedded clauses is semantically vacuous. We propose that the differences between CPs and TPs can be explained under a particular implementation of Kratzer’s ap- proach to the semantics of clausal embedding (Kratzer 2006, 2016; Bogal-Allbritten 2016, 2017; Moulton 2009, 2015; Elliott 2017), according to which CPs denote predicates of events whose content equals the embedded proposition. Keywords: semantics of clausal embedding, conjunction, disjunction, content CPs 1 Introduction Theories of clausal embedding seek to identify the contribution of the different syntactic pieces to the entailment patterns such sentences produce (1). In this paper we focus on the complementizer, or the abstract head COMP that it realizes, and ask: does it have a semantic contribution, and if so, what is it? (1) Maria thinks /knows /is upset [CP that Dina is dancing]. The classical semantics for attitude reports due to Hintikka(1969) assigned no meaning to the complementizer. On Hintikka’s theory (or a compositional rendering thereof, e.g. von Fintel & Heim 2011), the CP meaning inherits the mean- ing of the embedded TP—a proposition—with which the attitude verb composes: CP that Dina dances = TP Dina dances = fw : Dina dances in wg. -

Parts of Speech

Parts of Speech Created by Diedre Grafel. Kent Campus Learning Center, Communications Lab Updated 06-28-05 by South Campus Lab. Permission to copy and use is granted to all FCCJ staff provided this copyright label is displayed. For more information, visit the Learning Services web site: www.fccj.org/campuses/south/learning_cent/learning_cent.htm In each of the following lessons, read the definition of the part of speech. Check the examples for understanding. Then complete the exercises. The answers are included at the end of this handout. If you do not understand any part of the handout or the answers, please see a tutor in the South Campus Communications Lab, G-219. I. NOUN Definition: A noun names something and usually can form a plural (by adding –s or –es) except for non-count nouns such as information or transportation Persons George, man, people Animals cat, fish, dog Places Jacksonville, city, park Things paper, spoon, eraser Ideas happiness, horror, thought Exercise: Directions: Underline the nouns in each of the following sentences: 1. Jason enjoyed the movie about France. 2. The musicians play marching songs. 3. Music lovers thrill to the sound of trumpets. 4. Boys and girls are often eager to listen. 5. The conductor moves his baton vigorously. 6. There is no death penalty for criminals in Puerto Rico. 7. The "Explorer," crammed with scientific instruments, was launched on January 31, 1958. 8. New Mexico was admitted as a state in the twentieth century. 9. Chester Arthur was nominated for vice-president by the Republican Party in 1880. -

Phrasal and Sentential Conjunction in Transformational Grammar(船田) 143

名城論叢 2004年4月 141 Phrasal and Sentential Conjunction in Transformational Grammar Shukei Funada 1.Abstarct The present paper discusses two types of noun phrase conjunction in English from the congnitive linguistic views. This approach will shed some light on what is going on in the listener’s mind when he decodes and ecodes lingiuistc messages. 2.Phrasal and Sentential Conjunction There are two basic types of noun phrase conjunction, which we will callphrasaland sentential,based on the underlying P-marker from which each type derives. Correlating each type is a distinct type of semantic interpretation. When phrasal conjunction is involved, the act denoted by the verb phrase is an act shared by the two or more persons or things denoted by the conjoined noun phrases. For example, when we have a sentence such as ⑴,the act of conferring one act is shared by the two persons who confer with each other. ⑴ John and Mary conferred. Sentence ⑴ cannot be paraphrased by sentence ⑵. ⑵* John conferred and Mary conferred. When sentential conjunction is involved,each person or thing denoted by the conjoined noun phrases has its own act, as in ⑶. ⑶ John and Mary know the answer. That is, John’s knowing the answer and Mary’s knowing the answer are two distinct acts of knowing the answer since they cannot have a shared consciousness. Since two acts are involved, two underlying verb phrases are also involved, as indicated in ⑷, which is a para- phrase of ⑶. 142 第4巻 第4号 ⑷ John knows the answer and Mary knows the answer. Sentence ⑷ is derived by coordinate recursion from the underlying sentences ⑸ and ⑹.