SHAKESPEARE the ELIZABETHAN by Virgil K. Whitaker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plot? What Is Structure?

Novel Structure What is plot? What is structure? • Plot is a series of interconnected events in which every occurrence has a specific purpose. A plot is all about establishing connections, suggesting causes, and and how they relate to each other. • Structure (also known as narrative structure), is the overall design or layout of your story. Narrative Structure is about both these things: Story Plot • The content of a story • The form used to tell the story • Raw materials of dramatic action • How the story is told and in what as they might be described in order chronological order • About how, and at what stages, • About trying to determine the key the key conflicts are set up and conflicts, main characters, setting resolved and events • “How” and “when” • “Who,” “what,” and “where” Story Answers These Questions 1. Where is the story set? 2. What event starts the story? 3. Who are the main characters? 4. What conflict(s) do they face? What is at stake? 5. What happens to the characters as they face this conflict? 6. What is the outcome of this conflict? 7. What is the ultimate impact on the characters? Plot Answers These Questions 8. How and when is the major conflict in the story set up? 9. How and when are the main characters introduced? 10.How is the story moved along so that the characters must face the central conflict? 11.How and when is the major conflict set up to propel them to its conclusion? 12.How and when does the story resolve most of the major conflicts set up at the outset? Basic Linear Story: Beginning, Middle & End Ancient (335 B.C.)Greek philosopher and scientist, Aristotle said that every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. -

University Microfilms, a XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

72- 15,293 SHARP, Nicholas Andrew, 1944- SHAKESPEARE'S BAROQUE COMEDY: THE WINTER'S TALE. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, A XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED SHAKESPEARE'S BAROQUE CŒEDY: THE V/INTER'S TALE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicholas Andrew Sharp, B,A., M,A, ***** The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by Id^iser Department of English PLEASE NOTE: Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company Acknowledgraent I am extremely grateful to my adviser, Professor Rolf Soellner, for his advice, suggestions, and constant encouragement. ii VITA January 24, 1944 . Born— Kansas City, Missouri 1966 ......... B.A., The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 1966-1970........... NDEA Fellow, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1968-1969, 1971-1972 . Teaching Associate, Department of English, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 1968 .......... M.A., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENT..................................... ii VITA ..................................... .•.......... iii INTRODUCTION: BAROQUE AS AN HISTORICAL CONCEPT .... 1 Chapter I. THE JACOBEAN SETTING AND THE BAROQUE AESTHETIC 16 II. THE THEME OF SKEPTICAL FIDEISM............... 45 III. THE STRUCTURE............................... -

De Draagbare Wikipedia Van Het Schrijven – Verhaal

DE DRAAGBARE WIKIPEDIA VAN HET SCHRIJVEN VERHAAL BRON: WIKIPEDIA SAMENGESTELD DOOR PETER KAPTEIN 1 Gebruik, verspreiding en verantwoording: Dit boek mag zonder kosten of restricties: Naar eigen inzicht en via alle mogelijke middelen gekopieerd en verspreid worden naar iedereen die daar belangstelling in heeft Gebruikt worden als materiaal voor workshops en lessen Uitgeprint worden op papier Dit boek (en het materiaal in dit boek) is gratis door mij (de samensteller) ter beschikking gesteld voor jou (de lezer en gebruiker) en niet bestemd voor verkoop door derden. Licentie: Creative Commons Naamsvermelding / Gelijk Delen. De meeste bronnen van de gebruikte tekst zijn artikelen van Wikipedia, met uitzondering van de inleiding, het hoofdstuk Redigeren en Keuze van vertelstem. Deze informatie kon niet op Wikipedia gevonden worden en is van eigen hand. Engels In een aantal gevallen is de Nederlandse tekst te kort of non-specifiek en heb ik gekozen voor de Engelse variant. Mag dat zomaar met Wikipedia artikelen? Ja. WikiPedia gebruikt de Creative Commons Naamsvermelding / Gelijk Delen. Dit houdt in dat het is toegestaan om: Het werk te delen Het werk te bewerken Onder de volgende voorwaarden: Naamsvermelding (in dit geval: Wikipedia) Gelijk Delen (verspreid onder dezelfde licentie als Wikipedia) Link naar de licentie: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.nl Versie: Mei 2014, Peter Kaptein 2 INHOUDSOPGAVE INLEIDING 12 KRITIEK EN VERHAALANALYSE 16 Literaire stromingen 17 Romantiek 19 Classicisme 21 Realisme 24 Naturalisme 25 -

The Comic in the Theatre of Moliere and of Ionesco: a Comparative Study

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1965 The omicC in the Theatre of Moliere and of Ionesco: a Comparative Study. Sidney Louis Pellissier Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pellissier, Sidney Louis, "The omicC in the Theatre of Moliere and of Ionesco: a Comparative Study." (1965). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1088. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1088 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-744 PELLISSIER, Sidney Louis, 1938- s THE COMIC IN THE THEATRE OF MO LI ERE AND OF IONESCO: A COMPARATIVE STUDY. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1965 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE COMIC IN THE THEATRE OF MOLIHRE AND OF IONESCO A COMPARATIVE STUDY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Foreign Languages btf' Sidney L . ,') Pellissier K.A., Louisiana State University, 19&3 August, 19^5 DEDICATION The present study is respectfully dedicated the memory of Dr. Calvin Evans. ii ACKNO'.-'LEDGEKiNT The writer wishes to thank his major professor, Dr. -

Sachgebiete Im Überblick 513

Sachgebiete im Überblick 513 Sachgebiete im Überblick Dramatik (bei Verweis-Stichwörtern steht in Klammern der Grund artikel) Allgemelnes: Aristotel. Dramatik(ep. Theater)· Comedia · Comedie · Commedia · Drama · Dramaturgie · Furcht Lyrik und Mitleid · Komödie · Libretto · Lustspiel · Pantragis mus · Schauspiel · Tetralogie · Tragik · Tragikomödie · Allgemein: Bilderlyrik · Gedankenlyrik · Gassenhauer· Tragödie · Trauerspiel · Trilogie · Verfremdung · Ver Gedicht · Genres objectifs · Hymne · Ideenballade · fremdungseffekt Kunstballade· Lied· Lyrik· Lyrisches Ich· Ode· Poem · Innere und äußere Strukturelemente: Akt · Anagnorisis Protestsong · Refrain · Rhapsodie · Rollenlyrik · Schlager · Aufzug · Botenbericht · Deus ex machina · Dreiakter · Formale Aspekte: Bildreihengedicht · Briefgedicht · Car Drei Einheiten · Dumb show · Einakter · Epitasis · Erre men figuratum (Figurengedicht) ·Cento· Chiffregedicht· gendes Moment · Exposition · Fallhöhe · Fünfakter · Göt• Echogedicht· Elegie · Figur(en)gedicht · Glosa · Klingge terapparat · Hamartia · Handlung · Hybris · Intrige · dicht . Lautgedicht . Sonett · Spaltverse · Vers rapportes . Kanevas · Katastasis · Katastrophe · Katharsis · Konflikt Wechselgesang · Krisis · Massenszenen · Nachspiel · Perioche · Peripetie Inhaltliche Aspekte: Bardendichtung · Barditus · Bildge · Plot · Protasis · Retardierendes Moment · Reyen · Spiel dicht · Butzenscheibenlyrik · Dinggedicht · Elegie · im Spiel · Ständeklausel · Szenarium · Szene · Teichosko Gemäldegedicht · Naturlyrik · Palinodie · Panegyrikus -

Piecing Together the Puzzle of Contemporary Spanish Fiction: a Translation and Critical Analysis of Fricciones by Pablo Martín Sánchez

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 Piecing Together the Puzzle of Contemporary Spanish Fiction: A Translation and Critical Analysis of Fricciones by Pablo Martín Sánchez Madeleine Renee Calhoun Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the Reading and Language Commons, and the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Calhoun, Madeleine Renee, "Piecing Together the Puzzle of Contemporary Spanish Fiction: A Translation and Critical Analysis of Fricciones by Pablo Martín Sánchez" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 224. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/224 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Piecing Together the Puzzle of Contemporary Spanish Fiction: A Translation and Critical Analysis of Fricciones by Pablo Martín Sánchez Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Madeleine Calhoun AnnandaleonHudson, New York May 2016 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Patricia LópezGay, for her unwavering support and encouragement throughout the past year. -

Science Fiction Review 37

SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $2.00 WINTER 1980 NUMBER 37 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) Formerly THE ALIEN CRITZ® P.O. BOX 11408 NOVEMBER 1980 — VOL.9, NO .4 PORTLAND, OR 97211 WHOLE NUMBER 37 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY — $2.00 COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN SHORT FICTION REVIEWS "PET" ANALOG—PATRICIA MATHEWS.40 ASIMOV'S-ROBERT SABELLA.42 F8SF-RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON.43 ALIEN THOUGHTS DESTINIES-PATRICIA MATHEWS.44 GALAXY-JAFtS J.J, WILSON.44 REVIEWS- BY THE EDITOR.A OTT4I-MARGANA B. ROLAIN.45 PLAYBOY-H.H. EDWARD FORGIE.47 BATTLE BEYOND THE STARS. THE MAN WITH THE COSMIC ORIGINAL ANTHOLOGIES —DAVID A. , _ TTE HUNTER..... TRUESDALE...47 ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ. TRIGGERFINGER—an interview with JUST YOU AND Ft, KID. ROBERT ANTON WILSON SMALL PRESS NOTES THE ELECTRIC HORSEMAN. CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS.. .6 BY THE EDITOR.49 THE CHILDREN. THE ORPHAN. ZOMBIE. AND THEN I SAW.... LETTERS.51 THE HILLS HAVE EYES. BY THE EDITOR.10 FROM BUZZ DIXON THE OCTOGON. TOM STAICAR THE BIG BRAWL. MARK J. MCGARRY INTERFACES. "WE'RE COMING THROUGH THE WINDOW" ORSON SCOTT CARD THE EDGE OF RUNNING WATER. ELTON T. ELLIOTT SF WRITER S WORKSHOP I. LETTER, INTRODUCTION AND STORY NEVILLE J. ANGOVE BY BARRY N. MALZBERG.12 AN HOUR WITH HARLAN ELLISON.... JOHN SHIRLEY AN HOUR WITH ISAAC ASIMOV. ROBERT BLOCH CITY.. GENE WOLFE TIC DEAD ZONE. THE VIVISECTOR CHARLES R. SAUNDERS BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.15 FRANK FRAZETTA, BOOK FOUR.24 ALEXIS GILLILAND Tl-E LAST IMMORTAL.24 ROBERT A.W, LOWNDES DARK IS THE SUN.24 LARRY NIVEN TFC MAN IN THE DARKSUIT.24 INSIDE THE WHALE RONALD R. -

Adaptive Landscapes and Protein Evolution

Adaptive landscapes and protein evolution Maurício Carneiro and Daniel L. Hartl1 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 Edited by Diddahally R. Govindaraju, Boston University School of Medicine, and accepted by the Editorial Board August 31, 2009 (received for review July 10, 2009) The principles governing protein evolution under strong selection results with expectations based on computer simulations in are important because of the recent history of evolved resistance which the fitness of each combination of mutant sites is assigned to insecticides, antibiotics, and vaccines. One experimental ap- at random. We find that, in each case, mutant combinations in proach focuses on studies of mutant proteins and all combinations actual proteins show significantly more additive effects than of mutant sites that could possibly be intermediates in the evolu- would be expected by chance. These results are discussed in the tionary pathway to resistance. In organisms carrying each of the wider context of fitness landscapes in protein space. engineered proteins, a measure of protein function or a proxy for fitness is estimated. The correspondence between protein se- The Roads Not Taken quence and fitness is widely known as a fitness landscape or For every realized evolutionary path in sequence space there are adaptive landscape. Here, we examine some empirical fitness other roads not taken. General discussions of evolutionary landscapes and compare them with simulated landscapes in which pathways began ≈80 years ago in the work of Haldane (8) and the fitnesses are randomly assigned. We find that mutant sites in Wright (9). Wright’s article is far better known than Haldane’s, real proteins show significantly more additivity than those ob- probably because Wright’s had been written in response to a tained from random simulations. -

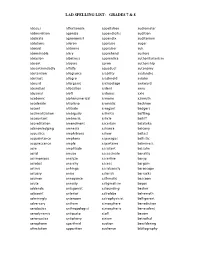

Lad Spelling List: Grades 7 & 8

LAD SPELLING LIST: GRADES 7 & 8 abacus affectionate appellation audiometer abbreviation agonize appendicitis audition abdicate agronomist appendix auditorium ablutions aileron appraise auger aboard airborne appraiser auk abominable alary apprehend austere abrasion albatross apprentice authoritarianism absent alcoves apron authorship absentmindedly alfalfa aqueduct autonomy abstention allegiance arability avalanche abstract allegro arachnoid aviator absurd allergenic archipelago awkward abundant allocation ardent awry abysmal aloft arduous axle academic alphanumerical armoire azimuth accelerate altiplano aromatic backhoe accent altitude arrogant badgers acclimatization ambiguity arthritis baffling accountant ambrosia article bailiff accreditation amendment ascertain balalaika acknowledging amnesia askance balcony acoustics amphibious askew ballast acquaintance amphora asparagus ballistic acquiescence ample aspartame balminess acre amplitude assailant balsalm acrid amuse assassinate banality acrimonious analyze assertive banjo acrobat anarchy assess bargain actinic anhinga assiduously baroscope actuary anise asterisk barracks acumen annoyance asthmatic bassoon acute annuity astigmatism bayou addenda antagonist astounding beaker adjacent anterior astrolabe behemoth admiringly anteroom astrophysicist belligerent adversary anthem atmosphere benediction aerobatics anthropologist atmospheric benevolent aerodynamic antipasto atoll besom aeronautics antiphony atrium betrothal aerophone apartheid auction bewildering affectation apparition audience -

Bibliothèque Et Archives Canada

National Ubrary :'~ nationalP. .+. of Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographie Services Branch des serviees bibliographiques 395 Wellnglon Street 395. rue WeI1lnglon ouawa. OrilallO Qnawa IOnlanO) K1A0N4 K1A0N4 NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualité de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the dépend grandement de la qualité quality of the original thesls de la thèse soumise au submitted for microfilming. mlcrofilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualité ensure the hlghest quality of supérieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S'il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec l'université degree. qui a conféré le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualité d'impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser à pages were typed with a poor désirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont été university sent us an inferlor dactylographiées à l'aide d'un photocopy. ruban usé ou si l'université nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualité inférieure. Reproduction ln full or in part of La reproduction, même partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, à la Loi canadienne sur le droit R.S.C. 1970, c. c-30, and d'auteur, SRC 1970, c. e-30, et subsequent amendments. ses amendements subséquents. Canada • The Intermediate State in Pauline Eschatology: An Exegesis of 2 Corinthians 5: 1-10 by Barbara Tychsen Harp Thesis submitted in partial'fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies McGil1 University, Montreal June, 1995 (f) Copyright by Barbara Tychsen Harp, 1995 • National Ubrary Bibliothèque nationale .+. -

High School Spelling & Vocabulary List and Rules for 2015-2016

basilisk canard harrumph zabaglione Word Power High School Spelling & Vocabulary List and Rules for 2015-2016 UNIVERSITY INTERSCHOLASTIC LEAGUE Making a World of Difference The Details... CAPITALIZATION If a word can begin with either a lowercase letter or a capital, both versions are given. It is the responsibility of the contestant to know in Word Power was compiled using The American what circumstances to use lowercase or capital Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, letters. Both the unnecessary use of a capital or third (1992) and fourth (2000) editions. Each its omission are considered errors. word was checked for possible variant spelling, capitalization, and parts of speech. Word Power refects several decisions made for consistency and clarity. MARKINGS The English language includes words taken SPELLING & PRONUNCIATION directly from foreign languages without changes in spelling. Marks assumed to be accent marks If a word has more than one correct spelling, for syllables are really guides to the proper all spellings are listed, separated by a comma pronunciation of vowels; therefore, in order (frenetic, phrenetic). Students are required to to spell the words correctly, it is necessary to spell only one variant. Although every attempt use these marks accurately. For example, the has been made to list all alternate spellings, French word dégagé is pronounced DAY gah some others will undoubtedly be discovered. ZHAY. The acute accent (´) is usually pronounced The American Heritage Dictionary of the English as the a in late or date. The grave (`) and the Language, Third, Fourth or Fifth Edition is the circumfex e (^) are pronounced as the e in peck fnal authority, not Word Power or the test lists. -

Dramatic Structure from Aristotle to Modern Times

Drama Dr. Abdel-Fattah Adel Upon the completion of this section, you will be able to: 1. To define "plot" as an element of drama 2. To summarize the development of the understanding of the dramatic structure from Aristotle to modern times. 3. To recognize the parts Freytag's pyramid of the development of dramatic plot. 4. To state the main criticism to Freytag's pyramid. 5. To apply Freytag's pyramid on a story line. Plot Dramatic structure Plot is a literary term for the events a story comprises, particularly as they relate to one another in a pattern, a sequence, through cause and effect, or by coincidence. It is the artistic arrangement of a sequence of events. Dramatic structure is the structure of a dramatic work such as a play or film. There is no difference between plot and dramatic structure. •Agree •Don’t agree There is no difference between plot and dramatic structure. Plot is related to the arrangement of the events. Dramatic structure is the overall layout of the story. There can be more than one plot in a play. •Agree •Don’t agree There can be more than one plot in a play. The play may contain a main plot a several sub-plots. Aristotle Horace Freytag In his Poetics, Aristotle considered plot ("mythos") the most important element of drama—more important than character, for example. He put forth the idea that ("A whole is what has a beginning and middle and end. This three-part view of a plot structure (with a beginning, middle, and end – technically, the protasis, epitasis, and catastrophe) must causally relate to one another as being either necessary, or probable.