C:\A Projects\AAA IBLA Decs\149IBLA\L287-293.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bakken Production Optimization Program Prospectus

Bakken Production Optimization Program BAKKEN PRODUCTION OPTIMIZATION PROGRAM 2.0 PROSPECTUS PROGRAM INTRODUCTION Led by the Energy & Environmental Research Center (EERC), the highly successful Bakken Production Optimization Program (BPOP), funded by its members and the North Dakota Industrial Commission, is continuing for the time frame of 2017–2020. The goal of this research program, BPOP 2.0, is to improve Bakken system oil recovery and reduce its environmental footprint. The results of the 3-year program will increase well productivity and the economic output of North Dakota’s oil and gas resources, decrease environmental impacts of wellsite operations, and reduce demand for infrastructure construction and maintenance. BPOP 1.0 PARTNERS A premier partnership program was recently completed which has been cited as an exemplary model by others nationwide. It has demonstrated that state lawmakers, state regulators, and industry can work together for positive results for shareholders and taxpayers alike. Phase I partners focused research on industry-driven challenges and opportunities. Continental Resources, Inc. ® Marathon Oil Corporation America’s Oil Champion Whiting Petroleum Corporation North Dakota Oil and Gas Research Program ConocoPhillips Company Nuverra Environmental Solutions Hitachi Hess Corporation Oasis Petroleum, Inc. SM Energy XTO Energy, Inc. BPOP 1.0 ACHIEVEMENTS (2013–2016) Continental’s Hawkinson Project Water Use and Handling Forecast Aimed at significantly increasing total production and A summary of trends in the Bakken, an estimation of production rates from North Dakota oil wells where oil future demand/disposal needs, an overview of treatment reserves of the second and third benches of the Three technologies, recycling/reuse considerations, and a Forks Formation, located just below the Bakken oil summary of implications for BPOP partners were created. -

Whiting Petroleum Corporation and Our Ability to Grow MMBOE: One Million BOE

Whiting Petroleum Corporation ANNUAL REPORT 8 0 0 2 NATU RAL HUM+AN Resources ABOUT THE COVER Having assembled a solid foundation of quality assets through acquisition, we are now more focused on organic drilling activity and on the development of previously acquired properties. We believe that our experienced team of management, engineering and geoscience professionals is generating superior results as evidenced by our reserves and production growth in the Bakken formation in North CONTENTS Dakota and our two CO 2 enhanced oil recovery projects. Corporate Profile 1 From our Bakken play in North Dakota, our average net daily production jumped 516% to 14,165 BOE in December 2008 Financial and Operations Summary 2 from 2,300 BOE in December 2007. We also completed Letter to the Shareholders 4 our first two infill wells in the Sanish field, which we believe Drilling and Operations Overview 7 adds a total of 78 potential infill well locations. Also of note was our first Three Forks horizontal well completion in the Northern Rockies 8 Sanish field. Production and pressure data from this well are Central Rockies 10 being analyzed to determine the viability of developing the Three Forks in the Sanish field. EOR Projects 12 Board of Directors 14 At our two EOR projects, our average net daily production Annual Report on Form 10-K 15 from the Postle and North Ward Estes fields increased 26% to 13,700 BOE in December 2008 from 10,900 BOE in Corporate Investor Information Inside back cover December 2007. We expect production from both EOR projects to continue to increase as 2009 progresses. -

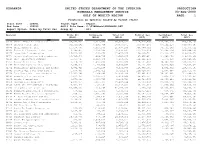

Ranking Operator by Gas 1999

PDRANKOP UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PRODUCTION MINERALS MANAGEMENT SERVICE 03-AUG-2000 GULF OF MEXICO REGION PAGE: 1 Production by Operator Ranked by Volume (4120) Start Date : 199901 Report Type : Report End Date : 199912 ASCII File Name: C:\TIMSWork\PDRANKOP.DAT Report Option: Order by Total Gas Group By : All Operator Crude Oil Condensate Total Oil Natural Gas Casinghead Total Gas (BBLS) (BBLS) (BBLS) (MCF) (MCF) (MCF) 02140 Shell Deepwater Production Inc. 85,672,533 9,411,739 95,084,272 245,810,790 213,353,317 459,164,107 00078 Chevron U.S.A. Inc. 50,545,262 6,292,709 56,837,971 353,305,284 87,102,210 440,407,494 00689 Shell Offshore Inc. 15,438,780 6,417,500 21,856,280 300,789,310 30,544,202 331,333,512 00003 Union Oil Company of California 6,344,477 2,334,388 8,678,865 253,150,024 15,694,524 268,844,548 00276 Exxon Mobil Corporation 16,626,406 1,243,669 17,870,075 168,330,701 51,313,377 219,644,078 00771 Texaco Exploration and Production Inc 10,785,640 1,908,736 12,694,376 187,865,901 31,396,468 219,262,369 00114 Amoco Production Company 1,853,723 2,410,438 4,264,161 182,121,250 1,573,019 183,694,269 01855 Vastar Resources, Inc. 7,750,730 1,435,200 9,185,930 114,537,982 34,747,390 149,285,372 01364 Newfield Exploration Company 4,368,048 2,162,039 6,530,087 132,431,383 10,633,590 143,064,973 02332 PennzEnergy Exploration and Production 5,772,629 3,160,145 8,932,774 118,870,351 9,572,802 128,443,153 00491 Coastal Oil & Gas Corporation 1,038,860 1,682,412 2,721,272 119,028,667 2,687,097 121,715,764 02219 Kerr-McGee Oil & Gas Corporation 13,307,198 1,569,590 14,876,788 102,681,653 14,762,861 117,444,514 00185 Samedan Oil Corporation 2,673,355 2,285,513 4,958,868 104,938,141 7,424,318 112,362,459 00105 Apache Corporation 6,574,028 1,660,755 8,234,783 92,723,545 12,356,983 105,080,528 00059 Amerada Hess Corporation 9,001,254 7,825,335 16,826,589 76,749,036 23,640,310 100,389,346 00540 MOBIL OIL EXPLORATION & PRODUCING SOUT 8,967,820 1,142,597 10,110,417 88,168,916 11,699,694 99,868,610 01680 BP Exploration & Oil Inc. -

Marathon Oil Corporation Creates Value by Responsibly Producing Oil and Natural Gas Vital to Meeting Growing Global Energy Needs

Create, Grow, Sustain: BUSINESS ROUNDTABLE Celebrating Success 2014 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT Marathon Oil Corporation creates value by responsibly producing oil and natural gas vital to meeting growing global energy needs. In doing so, we act responsibly toward our shareholders and business partners, support those who work for us, and strive to improve the communities where we operate. www.marathonoil.com/lov2012/index.shtml Our goal is to be recognized as the premier independent exploration and production company, and to accomplish this, we must successfully execute the strategic imperatives that guide our efforts. These imperatives begin with an uncompromising focus on our long-standing core values of health and safety, environmental stewardship, honesty and integrity, corporate citizenship, and a high-performance team culture. Our values help us protect our license to operate and drive business performance. We believe that developing oil To achieve sustainable and profitable growth, Marathon Oil is accelerating activity in our U.S. and gas resources in a safe, unconventional resource assets — the South Texas Eagle Ford Shale, North Dakota Bakken Shale and Oklahoma resource basins. These resource plays are at the forefront of the technology-driven environmentally sound and renaissance in the American oil and gas industry, which is making vast hydrocarbon resources available for the economic growth and energy security of our nation. responsible way is not only We recognize that the same spirit of technological discovery and innovation that is driving the possible, but also vital to the renaissance in the oil and gas industry can and will drive our ability to develop these important energy resources with less impact on the environment. -

2018 Annual Report

CALIFORNIA RESOURCES CORPORATION 2018 ANNUAL REPORT FINANCIAL AND OPERATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS Amounts in millions, except per-share amounts as of and for the years ended December 31, Financial Highlights 2018 2017 2016 Total Revenue $ 3,064 $ 2,006 $ 1,547 Income (Loss) Before Income Taxes $ 429 $ (262) $ 201 Net Income Attributable to Noncontrolling Interests $ 101 $ (4) $ - Net Income (Loss) Attributable to Common Stock $ 328 $ (266) $ 279 Adjusted Net Income (Loss)(a) $ 61 $ (187) $ (317) Net Income (Loss) Attributable to Common Stock per Share – Basic and Diluted(b) $ 6.77 $ (6.26) $ 6.76 Adjusted Net Income (Loss) per Share – Basic and Diluted(b) $ 1.27 $ (4.40) $ (7.85) Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities $ 461 $ 248 $ 130 Capital Investments $ 690 $ 371 $ 75 Net Payments on Debt $ 26 $ 18 $ 73 Net Cash Provided (Used) by Financing Activities $ 692 $ 73 $ (69) Total Assets $ 7,158 $ 6,207 $ 6,354 Long-Term Debt $ 5,251 $ 5,306 $ 5,168 Deferred Gain and Issuance Costs, Net $ 216 $ 287 $ 397 Equity $ (247) $ (720) $ (557) Weighted-Average Shares Outstanding(b) 47.4 42.5 40.4 Year-End Shares 48.7 42.9 42.5 Operational Highlights 2018 2017 2016 Production: Oil (MBbl/d) 82 83 91 NGLs (MBbl/d) 16 16 16 Natural Gas (MMcf/d) 202 182 197 Total (MBoe/d)(c) 132 129 140 Average Realized Prices: Oil with hedge ($/Bbl) $ 62.60 $ 51.24 $ 42.01 Oil without hedge ($/Bbl) $ 70.11 $ 51.47 $ 39.72 NGLs ($/Bbl) $ 43.67 $ 35.76 $ 22.39 Natural Gas ($/Mcf) $ 3.00 $ 2.67 $ 2.28 Reserves: Oil (MMBbl) 530 442 409 NGLs (MMBbl) 60 58 55 Natural Gas (Bcf) 734 706 626 Total (MMBoe)(c) 712 618 568 Organic Reserve Replacement Ratio(a) 127% 119% 71% PV-10 of Proved Reserves(a) (in billions) $ 9.4 $ 4.5 $ 2.8 Net Mineral Acreage (in thousands): Developed 701 703 717 Undeveloped 1,539 1,550 1,614 Total 2,240 2,253 2,331 Closing Share Price $ 17.04 $ 19.44 $ 21.29 (a) See www.crc.com, Investor Relations for a discussion of these non-GAAP measures, including a reconciliation to the most closely related GAAP measure or information on the related calculations. -

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Total score ACT rating Ranking out of 100 performance, narrative and trend 1 Neste 57.4 / 100 8.1 / 20 B 2 Engie 56.9 / 100 7.9 / 20 B 3 Naturgy Energy 44.8 / 100 6.8 / 20 C 4 Eni 43.6 / 100 7.3 / 20 C 5 bp 42.9 / 100 6.0 / 20 C 6 Total 40.7 / 100 6.1 / 20 C 7 Repsol 38.1 / 100 5.0 / 20 C 8 Equinor 37.9 / 100 4.9 / 20 C 9 Galp Energia 36.4 / 100 4.3 / 20 C 10 Royal Dutch Shell 34.3 / 100 3.4 / 20 C 11 ENEOS Holdings 32.4 / 100 2.6 / 20 C 12 Origin Energy 29.3 / 100 7.3 / 20 D 13 Marathon Petroleum Corporation 24.8 / 100 4.4 / 20 D 14 BHP Group 22.1 / 100 4.3 / 20 D 15 Hellenic Petroleum 20.7 / 100 3.7 / 20 D 15 OMV 20.7 / 100 3.7 / 20 D Total score ACT rating Ranking out of 100 performance, narrative and trend 17 MOL Magyar Olajes Gazipari Nyrt 20.2 / 100 2.5 / 20 D 18 Ampol Limited 18.8 / 100 0.9 / 20 D 19 SK Innovation 18.6 / 100 2.8 / 20 D 19 YPF 18.6 / 100 2.8 / 20 D 21 Compania Espanola de Petroleos SAU (CEPSA) 17.9 / 100 2.5 / 20 D 22 CPC Corporation, Taiwan 17.6 / 100 2.4 / 20 D 23 Ecopetrol 17.4 / 100 2.3 / 20 D 24 Formosa Petrochemical Corp 17.1 / 100 2.2 / 20 D 24 Cosmo Energy Holdings 17.1 / 100 2.2 / 20 D 26 California Resources Corporation 16.9 / 100 2.1 / 20 D 26 Polski Koncern Naftowy Orlen (PKN Orlen) 16.9 / 100 2.1 / 20 D 28 Reliance Industries 16.7 / 100 1.0 / 20 D 29 Bharat Petroleum Corporation 16.0 / 100 1.7 / 20 D 30 Santos 15.7 / 100 1.6 / 20 D 30 Inpex 15.7 / 100 1.6 / 20 D 32 Saras 15.2 / 100 1.4 / 20 D 33 Qatar Petroleum 14.5 / 100 1.1 / 20 D 34 Varo Energy 12.4 / 100 -

Strategic Decisions and Shareholder Value: an Analysis of Conocophillips Michael Miller University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Accounting Undergraduate Honors Theses Accounting 5-2012 Strategic decisions and shareholder value: an analysis of ConocoPhillips Michael Miller University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/acctuht Part of the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Michael, "Strategic decisions and shareholder value: an analysis of ConocoPhillips" (2012). Accounting Undergraduate Honors Theses. 3. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/acctuht/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Accounting at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Strategic Decisions and Shareholder Value: An Analysis of ConocoPhillips By Michael Cameron Miller Advisor: Ms. Susan Bristow An Honors Thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Bachelor of Science in Business Administration in Accounting Sam M. Walton College of Business University of Arkansas Fayetteville, Arkansas May 11, 2012 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................................................... -

California Resources Corporation (The “Company”) Believes Will Or May Occur in the Future Are Forward-Looking Statements

FINANCIAL AND OPERATING HIGHLIGHTS Dollar and share amounts in millions, except per-share amounts as of and for the years ended December 31, 2015 2014 2013 Financial Highlights Revenues $ 2,403 $ 4,173 $ 4,284 Income / (Loss) Before Income Taxes $ (5,476 ) $ (2,421 ) $ 1,447 Net Income / (Loss) $ (3,554 ) $ (1,434 ) $ 869 Adjusted Net Income / (Loss) (a) $ (311) $ 650 $ 869 EPS – Basic and Diluted (b) $ (9.27 ) $ (3.75 ) $ 2.24 Adjusted EPS – Basic and Diluted (b) $ (0.81) $ 1.67 $ 2.24 Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities $ 403 $ 2,371 $ 2,476 Capital Investments $ (401 ) $ (2,089 ) $ (1,669 ) Proceeds from Debt, Net $ 379 $ 6,360 — Cash Dividends to Occidental — $ (6,000 ) — Net Cash Provided (Used) by Financing Activities $ 352 $ (45) $ (763) Total Assets $ 7,053 $ 12,429 $ 14,297 Long-Term Debt – Principal Amount $ 6,043 $ 6,360 — Deferred Gain and Issuance Costs, Net $ 491 $ (68 ) — Equity / Net Investment $ (916) $ 2,611 $ 9,989 Weighted Average Shares Outstanding 383.2 381.9 — Year-End Shares 388.2 385.6 — Operational Highlights 2015 2014 2013 Production: Crude Oil (MBbl/d) 104 99 90 NGLs (MBbl/d) 18 19 20 Natural Gas (MMcf/d) 229 246 260 Total (MBoe/d) 160 159 154 Average Realized Prices: Crude with hedge ($/Bbl) $ 49.19 $ 92.30 $ 104.16 Crude without hedge ($/Bbl) $ 47.15 $ 92.30 $ 104.16 NGLs ($/Bbl) $ 19.62 $ 47.84 $ 50.43 Natural Gas with hedge ($/Mcf) $ 2.66 $ 4.39 $ 3.73 Reserves: Crude Oil (MMBbl) 466 551 532 NGLs (MMBbl) 59 85 71 Natural Gas (Bcf) 715 790 844 Total (MBoe/d) 644 768 744 Acreage (in thousands): Net Developed 736 716 701 Net Undeveloped 1,653 1,691 1,604 Total 2,389 2,407 2,305 Closing Share Price $ 2.33 $ 5.51 (a) For discussion of, or reconciliation to the most closely-related GAAP measure, see “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations – Results,” in our Form 10-K. -

Big Oil Goes to College an Analysis of 10 Research Collaboration Contracts Between Leading Energy Companies and Major U.S

ISTOCKPHOTO/SSHEPHARD Big Oil Goes to College An Analysis of 10 Research Collaboration Contracts between Leading Energy Companies and Major U.S. Universities Jennifer Washburn October 2010 (updated) WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG ii Center for American Progress | Big Oil Goes Back to College Big Oil Goes to College An Analysis of 10 Research Collaboration Contracts between Leading Energy Companies and Major U.S. Universities Jennifer Washburn With research assistance from Derrin Culp, and legal analysis and interpretation of university-industry research agreements by Jeremiah Miller October 2010 Contents 1 Preface 5 Introduction and summary 29 Energy research at U.S. universities 32 The university perspective 38 The energy industry perspective 45 The U.S. government perspective 49 A detailed analysis of 10 university-industry agreements to finance energy research 52 Table: Summary of main contract analysis findings 60 Overview of the 10 agreements: Major findings 69 Recommendations 74 Conclusion 75 Appendix one—Detailed contract review Arizona State University & BP Technology Ventures, Inc., a unit of BP PLC 85 Appendix two—Detailed contract review Energy Biosciences Institute University of California at Berkeley; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign & BP Technology Ventures, Inc., a unit of BP PLC 106 Appendix three —Detailed contract review University of California at Davis & Chevron Technology Ventures, LLC, a unit of Chevron Corp. 114 Appendix four—Detailed contract review Chevron Center of Research Excellence Colorado School of Mines & ChevronTexaco Energy Technology Co., a unit of Chevron Corp. 122 Appendix five—Detailed contract review Colorado Center for Biorefining and Biofuels University of Colorado, Boulder; Colorado State University; Colorado School of Mines; National Renewable Energy Laboratory & Numerous industrial partners 135 Appendix six—Detailed contract review Georgia Institute of Technology & Chevron Technology Ventures LLC, a unit of Chevron Corp. -

Chevron Usa Inc

Case Number: PC-2018-4716 Filed in Providence/Bristol County Superior Court Submitted: 1/13/2020 11:48 PM Envelope: 2422242 Reviewer: Carol M. STATE OF RHODE ISLAND SUPERIOR COURT PROVIDENCE, SC. STATE OF RHODE ISLAND, : Plaintiff, : : v. : : P.C. No. 2018-4716 CHEVRON CORP.; : CHEVRON U.S.A. INC.; : EXXONMOBIL CORP.; : BP P.L.C.; : BP AMERICA, INC.; : BP PRODUCTS NORTH AMERICA, : INC.; : ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC; : MOTIVA ENTERPRISES, LLC; : SHELL OIL PRODUCTS COMPANY : LLC; : CITGO PETROLEUM CORP.; : CONOCOPHILLIPS; : CONOCOPHILLIPS COMPANY; : PHILLIPS 66; : MARATHON OIL COMPANY; : MARATHON OIL CORPORATION; : MARATHON PETROLEUM CORP.; : MARATHON PETROLEUM COMPANY : LP; : SPEEDWAY LLC; : HESS CORP.; : LUKOIL PAN AMERICAS, LLC; : GETTY PETROLEUM MARKETING, : INC.; AND : DOES 1 through 100, inclusive : Defendants. DEFENDANTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS FOR FAILURE TO STATE A CLAIM UPON WHICH RELIEF CAN BE GRANTED Case Number: PC-2018-4716 Filed in Providence/Bristol County Superior Court Submitted: 1/13/2020 11:48 PM Envelope: 2422242 Reviewer: Carol M. Pursuant to R.I. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6), Defendants1 Chevron Corporation; Chevron U.S.A., Inc.; Exxon Mobil Corporation; BP Products North America Inc.; BP P.L.C.; BP America Inc.; Royal Dutch Shell, PLC; Motiva Enterprises, LLC; Shell Oil Products Company LLC; Citgo Petroleum Corporation; ConocoPhillips; ConocoPhillips Company; Phillips 66; Marathon Petroleum Corporation; Marathon Petroleum Company LP; Speedway, LLC; Hess Corp.; Marathon Oil Company; and Marathon Oil Corporation collectively move this Court to dismiss Plaintiff’s Complaint with prejudice for failure to state a claim. Defendants rely upon the Complaint, all prior pleadings and proceedings and the contemporaneously filed Memorandum of Law in Support of Defendants’ Motion for Failure to State a Claim Upon Which Relief Can be Granted.2 Dated: January 13, 2020 Respectfully submitted, /s/ Gerald J. -

APACHE CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): May 13, 2014 APACHE CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 1-4300 41-0747868 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 2000 Post Oak Boulevard Suite 100 Houston, Texas 77056-4400 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (713) 296-6000 Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-Commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Item 5.02. Departure of Directors or Certain Officers; Election of Directors; Appointment of Certain Officers; Compensatory Arrangements of Certain Officers On May 13, 2014, the Board appointed Ms. Annell R. Bay as a new director of Apache Corporation (the “Company”). On May 14, 2014, the Company issued a press release announcing this appointment, a copy of which is filed herewith as Exhibit 99.1. Ms. -

Effective Tax Rates for Oil and Gas Companies

Effective Tax Rates of Oil and Gas Companies: Cashing in on Special Treatment July 2014 Table of Contents Page Results in Brief …………………………………………………………………….. 3 Discussion ……………………………………………………………………………. 4 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………… 6 Notes …………………………………………………………………………………… 6 U.S. Federal Effective Tax Rates, 2009-2013 …………………………… 7 Foreign Effective Tax Rates, 2009-2013 ………………………………..... 8 Deferred Tax Liabilities from Property, Plant, and Equipment in 2012 and 2013……………………………………………………………………….. 9 Appendix: Company Profiles ExxonMobil Corporation ……………………………………………......... 10 ConocoPhillips …………………………………………………………………. 12 Occidental Petroleum Corporation …………………………………….. 14 Chevron Corporation ………………………………………………………… 15 Anadarko Petroleum Corporation ………………………………………. 17 Chesapeake Energy Corporation …………………………………......... 19 EOG Resources, Inc. …………………………………………………........ 20 Devon Energy Corporation …………………………………………......... 22 Apache Corporation ………………………………………………………….. 23 Pioneer Natural Resources Company ………………………………….. 25 Continental Resources, Inc. ……………………………………………… 27 Marathon Oil Corporation …………………………………………………. 28 Hess Corporation ……………………………………………………………… 29 Range Resources Corporation ……………………………………………. 30 Plains Exploration & Production Company …………………………. 31 SandRidge Energy, Inc. ……………………………………………………. 33 Whiting Petroleum Corporation …………………………………………. 34 Denbury Resources, Inc. ………………………………………………….. 35 Noble Energy, Inc. …………………………………………………………… 36 Concho Resources Inc. …………………………………………………….. 37 Company Notes …………………………………………………………………