Sand Dune Management Techniques & Preliminary Decision Support Tool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PENHALE DUNES from the Website Cornwall for the Book Discover Butterflies in Britain © D E Newland 2009

PENHALE DUNES from www.discoverbutterflies.com the website Cornwall for the book Discover Butterflies in Britain © D E Newland 2009 South-West Coast Path looking south from Holywell There are several square miles In 1939 a military camp was TARGET SPECIES of high sand dunes at Penhale set up at Holywell and the Sands on nthe north Cornwall MoD still has a large part of Dingy and Grizzled Skippers, coast near Perranporth. These the northern end of the dunes Brown Argus, Small Copper, have a wide range of maritime fences off. However there are Common Blue, Wall (all in the flora and include some vast areas of the dunes with spring), Small Heath, Marbled important archaeological nopen access. There is a White, Silver-studded Blue remains. Sheltered areas National Trust car park at the (later) with occasional between the dunes are good northern end at Holywell and sightings of many other for Silver-studded Blues in the there are several lay-bys on species probable. summer and, in the spring, you the minor road that runs along may find the rare Grizzled the eastern edge of the dunes. Skipper ab taras. The South-West Coast Path runs along its western edge. Penhale Dunes is now a candidate Special Area of Conservation under European rules. According to legend, St Piran brought Christianity to Cornwall from Ireland in the 6th century. This was the result of a lucky escape, because Piran was thrown into the sea with a millstone around his neck. But the millstone turned out to be lighter than water and floated, so the wind and the waves brought Piran to Cornwall. -

Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING

5k Environmentol Protection Report WATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 April 1992 FW P/9 2/ 0 0 1 Author: B Steele Technicol Assistant, Freshwater NRA National Rivers Authority CVM Davies South West Region Environmental Protection Manager HATER QUALITY MONITORING LOCATIONS 1992 _ . - - TECHNICAL REPORT NO: FWP/92/001 The maps in this report indicate the monitoring locations for the 1992 Regional Water Quality Monitoring Programme which is described separately. The presentation of all monitoring features into these catchment maps will assist in developing an integrated approach to catchment management and operation. The water quality monitoring maps and index were originally incorporated into the Catchment Action Plans. They provide a visual presentation of monitored sites within a catchment and enable water quality data to be accessed easily by all departments and external organisations. The maps bring together information from different sections within Water Quality. The routine river monitoring and tidal water monitoring points, the licensed waste disposal sites and the monitored effluent discharges (pic, non-plc, fish farms, COPA Variation Order [non-plc and pic]) are plotted. The type of discharge is identified such as sewage effluent, dairy factory, etc. Additionally, river impact and control sites are indicated for significant effluent discharges. If the watercourse is not sampled then the location symbol is qualified by (*). Additional details give the type of monitoring undertaken at sites (ie chemical, biological and algological) and whether they are analysed for more specialised substances as required by: a. EC Dangerous Substances Directive b. EC Freshwater Fish Water Quality Directive c. DOE Harmonised Monitoring Scheme d. DOE Red List Reduction Programme c. -

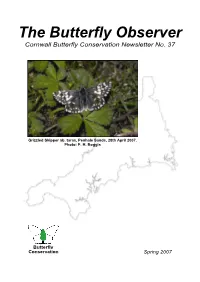

Spring Newsletter No.37

The Butterfly Observer Cornwall Butterfly Conservation Newsletter No. 37 Grizzled Skipper ab. taras, Penhale Sands, 28th April 2007. Photo: P. H. Boggis Butterfly Conservation Spring 2007 The Butterfly Observer - Spring 2007 Editorial his issue continues our environmental theme by including an article from the Western Morning News about pony grazing on Penhale Sands (see page 5). TMore about the Grizzled Skipper, aberration taras on page 3. There have been some very early records of various species sent in by one or two of our members. Indeed this spring has proved to be advanced by at least three weeks. An article by Sally Foster, our transect co-ordinator about the site at Church Hay Down appears on page 6. Many thanks to Tim Dingle for again providing us with the minutes of the latest meeting of the Cornwall Fritillary Action Group (see p.12). I feel this to be an important item, therefore, space permitting, all CFAG minutes will be included in the Butterfly Observer unless I hear from members to the contrary. An in depth analysis of separating the Pearl-bordered from the Small Pearl-bordered Fritillary appears on page 16. On the ‘mothing’ front there is an article on page 11 about Pyrausta cingulata which has been mentioned briefly before on page 9 of issue 26, Autumn 2003. Roger Lane again joins in the reports with one about the Orange Underwing on page 10. A question about lekking appears on page 17. Some good news from Mary Ellen Ryall, editor of ‘Happy Tonics’ appears on the following page. Finally, please find details of Tim & Sandy Dingle’s Garden Open Day on page 18. -

The Bryophytes of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly

THE BRYOPHYTES OF CORNWALL AND THE ISLES OF SCILLY by David T. Holyoak Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 3 Scope and aims .......................................................................... 3 Coverage and treatment of old records ...................................... 3 Recording since 1993 ................................................................ 5 Presentation of data ................................................................... 6 NOTES ON SPECIES .......................................................................... 8 Introduction and abbreviations ................................................. 8 Hornworts (Anthocerotophyta) ................................................. 15 Liverworts (Marchantiophyta) ................................................. 17 Mosses (Bryophyta) ................................................................. 98 COASTAL INFLUENCES ON BRYOPHYTE DISTRIBUTION ..... 348 ANALYSIS OF CHANGES IN BRYOPHYTE DISTRIBUTION ..... 367 BIBLIOGRAPHY ................................................................................ 394 1 Acknowledgements Mrs Jean A. Paton MBE is thanked for use of records, gifts and checking of specimens, teaching me to identify liverworts, and expertise freely shared. Records have been used from the Biological Records Centre (Wallingford): thanks are due to Dr M.O. Hill and Dr C.D. Preston for -

Defence Infrastructure Organisation Contacts

THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE CONSERVATION MAGAZINE Number 40 • 2011 Defending Development Recreating the Contemporary Operating Environment Satellite tracking gannets Bempton Cliffs, East Yorkshire Help for Heroes Tedworth House Conservation Group Editor Clare Backman Photography Competition Defence Infrastructure Organisation Designed by Aspire Defence Services Ltd Multi Media Centre Editorial Board John Oliver (Chairman) Pippa Morrison Ian Barnes Tony Moran Editorial Contact Defence Infrastructure Organisation Building 97A Land Warfare Centre Warminster Wiltshire BA12 0DJ Email: [email protected] Tel: 01985 222877 Cover image credit Winner of Conservation Group Photography Competition Melita dimidiata © Miles Hodgkiss Sanctuary is an annual publication about conservation of the natural and historic environment on the defence estate. It illustrates how the Ministry of Defence (MOD) is King penguin at Paloma Beach © Roy Smith undertaking its responsibility for stewardship of the estate in the UK This is the second year of the MOD window. This photograph has great and overseas through its policies Conservation Group photographic initial impact and a lovely image to take! and their subsequent competition and yet again we have had The image was captured by Hugh Clark implementation. It an excellent response with many from Pippingford Park Conservation is designed for a wide audience, wonderful and interesting photos. The Group. from the general public, to the Sanctuary board and independent judge, professional photographer David Kjaer Highly commended was the photograph people who work for us or (www.davidkjaer.com), had a difficult above of a king penguin at Paloma volunteer as members of the MOD choice but the overall winner was a beach, Falkland Islands, taken by Roy Conservation Groups. -

Polruan to Polperro SAC Conservation Objectives

European Site Conservation Objectives: Supplementary advice on conserving and restoring site features Polruan to Polperro Special Area of Conservation (SAC) Site Code: UK0030241 Photo credit: David Hazlehurst Date of Publication: 11 February 2019 Page 1 of 30 About this document This document provides Natural England’s supplementary advice about the European Site Conservation Objectives relating to Polruan to Polperro SAC. This advice should therefore be read together with the SAC Conservation Objectives available here. You should use the Conservation Objectives, this Supplementary Advice and any case-specific advice given by Natural England, when developing, proposing or assessing an activity, plan or project that may affect this site. This Supplementary Advice to the Conservation Objectives presents attributes which are ecological characteristics of the designated species and habitats within a site. The listed attributes are considered to be those that best describe the site’s ecological integrity and which, if safeguarded, will enable achievement of the Conservation Objectives. Each attribute has a target which is either quantified or qualitative depending on the available evidence. The target identifies as far as possible the desired state to be achieved for the attribute. The tables provided below bring together the findings of the best available scientific evidence relating to the site’s qualifying features, which may be updated or supplemented in further publications from Natural England and other sources. The local evidence used in preparing this supplementary advice has been cited. The references to the national evidence used are available on request. Where evidence and references have not been indicated, Natural England has applied ecological knowledge and expert judgement. -

1 Minutes of Cornwall AONB Partnership Meeting Held On

Minutes of Cornwall AONB Partnership Meeting held on Tuesday 5 December 2017 at 12.45pm at The Fowey Hotel, Esplanade, Fowey In Attendance Members: Bob Kirby-Harris Chair (outgoing), Cornwall AONB Partnership Gill Pipkin Chair (newly elected), Cornwall AONB Partnership Dominic Fairman Cornwall Councillor Jim Flashman Cornwall Councillor Martyn Alvey Cornwall Councillor Rhiannon Pipkin Natural England Gary Lewis ERCCIS/Cornwall Wildlife Trust Helen Rawe Cornwall Heritage Trust Ainsley Cocks Cornish Mining World Heritage Site Lucy Morris Westcountry Rivers Trust Ann Preston-Jones Historic England Tim Light Fal River Cornwall Becky Hughes FWAG South West Supporting officers: Peter Marsh Cornwall Council, Environment Service Director Ann Reynolds Cornwall Council, Historic Environment Colette Beckham Cornwall AONB Partnership Manager Jane Davies Cornwall AONB Development Officer Jim Wood Cornwall AONB Planning Officer Chris Coldwell Cornwall AONB Project Development Officer Karen Johns Cornwall AONB Office & Finance Manager Claire Hoddinott, Fowey Harbour Commissioners, also attended to provide a presentation on the work of the Fowey Estuary Partnership. Welcome Bob Kirby-Harris welcomed everyone to the meeting. There were some new representatives, including the Cornwall Councillors who have been nominated to represent Cornwall Council on the Cornwall AONB Partnership: Cllrs Martyn Alvey; Dominic Fairman; Jim Flashman; Loic Rich (Loic Rich had given apologies for 1 this meeting). Gill Pipkin, was also welcomed, and will be the new Cornwall -

Cornwall Coast Path Free

FREE CORNWALL COAST PATH PDF Henry Stedman,Joel Newton,Daniel McCrohan | 352 pages | 20 Jul 2016 | Trailblazer Publications | 9781905864713 | English | Hindhead, Surrey, United Kingdom The Most Beautiful Coastal Walks in Cornwall Culture Trip stands with Black Lives Matter. Select currency. My Plans. Open menu Menu. St Agnes to Perranporth Hiking Trail. Add to Plan. A short walk of 3. The ascent takes you out of Cornwall Coast Path valley, when Trevaunance Cove bursts into view. With just one steep up-and-down, amble along turquoise coves accessible only to kayaks and surfers. Your final view as you enter Perranporth will be line after line of waves breaking on the beach. Get some well-deserved rest at this gorgeous stone cottagea short stroll from the beach at St Agnes, with its welcoming restaurants and pubs. Built on the ocean-facing land of the West Polberro mine, the one-bedroom cottage can sleep three, and makes the perfect romantic escape. More Info. Open In Google Maps. Visit website. Clinging to the edge of southeast Cornwall and just a seven-minute boat trip from Plymouth, Mount Edgcumbe boasts gardens that are a heady-scented wonderland of flowers. With stunning views of Plymouth Sound and the South Devon coast, follow Cornwall Coast Path pathway until you reach a stretch of grassland known as Minadew Brakes. After a breather, zigzag through woodland and across beaches until you reach the twin villages of Kingsand and Cawsand. The Cross Keys Inn in Cawsand has an excellent range of local ales, with outside seating and live music on Sundays. -

CORNWALL 218 Atmospheric of All, During the Roaring Surf Andbitter Windsofcornwall’Sferalatmospheric Ofall,Duringtheroaringsurf Winter

© Lonely Planet Publications 218 lonelyplanet.com THE NORTH COAST 219 Orientation & Information detail on ways to get to and from the county Cornwall stretches from the River Tamar and p295 for countywide travel. C o r n w a l l and the granite hump of Dartmoor in the Cornwall 24 (www.cornwall24.co.uk) Lively (and usually east all the way to mainland England’s most heated) Cornwall discussion forum. westerly point at Land’s End. The principal Cornwall Beach Guide (www.cornwallbeachguide administrative town, Truro, sits bang in the .co.uk) Online guide to the county’s finest sand. middle of the county; to the north are the Cornwall Online (www.cornwall-online.co.uk) A lofty cliffs and surfing beaches of the north community-based site with guides to accommodation, And gorse turns tawny orange, seen beside coast, while the south coast is a gentler walks, attractions, villages and activities. Pale drifts of primroses cascading wide landscape of fields, river estuaries and quiet To where the slate falls sheer into the tide. beaches. The main A30 road cuts through the middle of the county, running roughly THE NORTH COAST Sir John Betjeman, Cornish Cliffs parallel with the main-line railway between London Paddington and Penzance; a second If it’s the classic Cornish combination of Jutting out into the churning sea and cut off from south Devon by the broad River Tamar, major road (the A38) runs east from Ply- lofty cliffs, sweeping bays and white-horse Cornwall (or Kernow, as its usually known around these shores) has always seen itself as a mouth across the Tamar Bridge and along surf you’re after, then make a beeline for the nation apart from the rest of England – another country, not just another English county. -

Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern

Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern 14 Post-Medieval, Industrial and Modern Edited by Mike Bone and David Dawson from contributions by Mike Bone, David Cranstone, David Dawson, David Hunt, Oliver Kent, Mike Ponsford, Andy Pye and Chris Webster Introduction • From c.1540 there was a step-change in the rate of exploitation of our natural resources leading The western aspect of the South West was impor- to radical changes to the landscape. The exploita- tant in earlier times, but during this period it became tion of water for power, transport and later paramount as the strategic interests of Britain devel- the demand for clean drinking water produced oped, first across the Atlantic and then globally. The spectacular changes which apart from individual development of the great naval base at Devonport is monument studies have been largely undocu- an indication of this (Coad 1983). Understanding the mented. Later use of coal-based technology led archaeology of the South West is therefore interde- to the concentration of production and settle- pendent on archaeological work on an international ment in towns/industrial villages. scale and vice versa. The abundance of resources in the region (fuels: coal and natural gas, raw materials • Exploitation for minerals has produced equally for the new age: arsenic, calamine, wolfram, uranium, distinctive landscapes and has remodelled some china clay, ball clay, road stone, as well as traditionally of the “natural” features that are now regarded exploited materials such as copper, tin, lead, agricul- as iconic of the South West, for example, the tural produce and fish) ensured that the region played Avon and Cheddar Gorges, the moorland land- a full part in technological and social changes. -

Ref: LCAA1820

Ref: LCAA6945 Guide £1,100,000 Sunset, Ramoth Way, Perranporth, Cornwall FREEHOLD An unrivalled opportunity to acquire an exceptional, contemporary coastal house with over 4,000sq.ft. of incredibly spacious well presented accommodation. Enjoying a sensational elevated location backing onto the sand dunes of Perranporth golf course and enjoying fantastic far reaching south westerly views over the village and the golden sand surf beach below. 2 Ref: LCAA6945 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Ground Floor: entrance hall, wc, kitchen/breakfast room (33’2” x 19’7”), utility room. Triple aspect sitting/dining room (33’2” x 19’7”), study/4th bedroom. First Floor: landing, vast master bedroom suite including bedroom (20’7” x 19’7”), sun room with private sundeck and en-suite bath/shower/dressing room. Guest bedroom with en-suite bathroom, 3rd double bedroom with en-suite shower room. Outside: integral double garage (29’6” x 20’1”), storage cupboard, boiler room. Parking for numerous vehicles with additional gravelled parking area off Ramoth Way. Front sun terrace. Rear terrace with firepit. Raised terrace with pergola, fishpond. Summerhouse and jacuzzi. Oil tank shed. DESCRIPTION 3 Ref: LCAA6945 • Constructed in 2013, Sunset is an exceptional detached contemporary coastal home built to an exacting standard faced with Cornish granite and composite weatherboarding under a Bradstone tiled roof. With the benefit of the remainder of a 10 Year Build Zone Warranty. • 4,085sq.ft of incredibly spacious accommodation, the dimensions of which need to be seen first hand to be fully appreciated. • Occupying a sensational elevated setting off Ramoth Way, a private no-through lane, the property backs onto the sand dunes of Perranporth golf course and as its name 4 Ref: LCAA6945 Sunset suggests basks in afternoon sunlight and enjoys beautiful sunsets from the last rays of the setting sun. -

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report 1992 SURVEY OF

N J f s A 5 ^2.>f> 3 _ Environmental Protection Final Draft Report 1992 SURVEY OF BATHING WATER QUALITY December 1992 TWU/92/17 Author: S Culling Assistant Scientist (Tidal Waters) NRA C.V.M. Davies National Rivers Authority Environmental Protection Manager South West Region MONITORING OF TIDAL WATERS FOR BATHING WATER QUALITY DURING 1992 REPORT NO TWU/92/17 SUMMARY The 1992 survey of Bathing Waters has been completed. Of the 134 EC identified Bathing Waters monitored during 1992, 117 complied with the principle bacteriological parameters total and faecal coliforms. Seventeen bathing waters failed to meet these standards. Four of these seventeen waters have not failed in previous years. S Culling Assistant Scientist (Tidal Waters) December 1992 CONTENTS Page Number 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. 1992 SURVEY - EC Identified Bathing Waters 2 - Non Identified Bathing Waters 4 3. DoE POSTER SCHEME 4 4. AESTHETIC SURVEY 4 5. FUTURE WORK 4 APPENDICES 1992 SURVEY OP BATHING WATER QUALITY 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The National Rivers Authority (NRA) is the competent authority, in England and Wales, for the implementation of the European Commission Directive Concerning the Quality of Bathing Water. 1.2 In the South West there are 135 bathing waters identified under the Directive. 134 of these were sampled in 1992 in accordance with the requirements of the Directive. Porthleven (East) remains inaccessible until the steps to the beach (destroyed in 1989 by a landslide) are replaced. 1.3 In April, the Department of the Environment, DoE, added Porthcothan bathing water (North Cornwall) to the list of EC identified bathing waters.