The Marvel Cinematic Universe (Mcu): the Evolution of Transmedial to Spherical Modes of Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man #16 Fantastic Four #7 Daredevil #2 Avengers No Road Home #3 (of 10) Superior Spider-Man #3 Age of X-Man X-Tremists #1 (of 5) Captain America #8 Captain Marvel Braver & Mightier #1 Savage Sword of Conan #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Betrayed #1 ($1) Invaders #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Avenger #1 ($1) Black Panther #9 X-Force #3 Marvel Comics Presents #2 True Believers Captain Marvel New Ms Marvel #1 ($1) West Coast Avengers #8 Spider-Man Miles Morales Ankle Socks 5-Pack Star Wars Doctor Aphra #29 Black Panther vs. Deadpool #5 (of 5) Marvel Previews Captain Marvel 2019 Sampler (FREE) Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #40 Mr. and Mrs. X Vol. 1 GN Spider-Geddon Covert Ops GN Iron Fist Deadly Hands of Kung Fu Complete Collection GN Marvel Knights Punisher by Peyer & Gutierrez GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Heroes in Crisis #6 (of 9) Flash #65 "The Price" part 4 (of 4) Detective Comics #999 Action Comics #1008 Batgirl #32 Shazam #3 Wonder Woman #65 Martian Manhunter #3 (of 12) Freedom Fighters #3 (of 12) Batman Beyond #29 Terrifics #13 Justice League Odyssey #6 Old Lady Harley #5 (of 5) Books of Magic #5 Hex Wives #5 Sideways #13 Silencer #14 Shazam Origins GN Green Lantern by Geoff Johns Book 1 GN Superman HC Vol. 1 "The Unity Saga" DC Essentials Nightwing Action Figure NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Man-Eaters #6 Die Die Die #8 Outcast #39 Wicked & Divine #42 Oliver #2 Hardcore #3 Ice Cream Man #10 Spawn #294 Cold Spots GN Man-Eaters Vol. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Feb COF C1:Customer 1/6/2012 2:54 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18FEB 2012 FEB E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG 02 FEBRUARY COF Apparel Shirt Ad:Layout 1 1/11/2012 1:45 PM Page 1 DC HEROES: “SUPER POWERS” Available only TURQUOISE T-SHIRT from your local comic shop! PREORDER NOW! SPIDER-MAN: DEADPOOL: “POOL SHOT” PLASTIC MAN: “DOUBLE VISION” BLACK T-SHIRT “ALL TIED UP” BURGUNDY T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! CHARCOAL T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! PREORDER NOW! COF Gem Page February:gem page v18n1.qxd 1/11/2012 1:29 PM Page 1 STAR WARS: MASS EFFECT: BLOOD TIES— HOMEWORLDS #1 BOBA FETT IS DEAD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS (OF 4) DARK HORSE COMICS WONDER WOMAN #8 DC COMICS RICHARD STARK’S PARKER: STIEG LARSSON’S THE SCORE HC THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON IDW PUBLISHING TATTOO SPECIAL #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO SECRET #1 IMAGE COMICS AMERICA’S GOT POWERS #1 (OF 6) AVENGERS VS. X-MEN: IMAGE COMICS VS. #1 (OF 6) MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 1/12/2012 10:00 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Girl Genius Volume 11: Agatha Heterodyne and the Hammerless Bell TP/HC G AIRSHIP ENTERTAINMENT Strawberry Shortcake Volume 1: Berry Fun TP G APE ENTERTAINMENT Bart Simpson‘s Pal, Milhouse #1 G BONGO COMICS Fanboys Vs. Zombies #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 Roger Langridge‘s Snarked! Volume 1 TP G BOOM! STUDIOS/KABOOM! Lady Death Origins: Cursed #1 G BOUNDLESS COMICS The Shadow #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT The Shadow: Blood & Judgment TP G D. -

Abbott Downloads Over 800 Instant Downloads

2013 ABBOTT DOWNLOADS OVER 800 INSTANT DOWNLOADS Thank you for taking the time to download this catalog. We have organized the downloads as they are on the website – Books, Manuscripts, Workshop Plans, Tops Magazines, Free With Purchase. Clicking on a link will take you directly to that category. Greg Bordner Abbott Magic Company 1/26/2013 Contents ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE BOOKS ................................................................................................. 5 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE MANUSCRIPTS .................................................................................. 8 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE WORKSHOP PLANS ....................................................................... 11 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE TOPS MAGAZINES ......................................................................... 15 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE INSTRUCTIONS .............................................................................. 17 ABBOTT FREE DOWNLOADS ........................................................................................................... 46 ABBOTT DOWNLOADABLE BOOKS All Abbott Book Downloads are $4 – Downloads are instant if you use PayPal Book 15 Great Illusions Book 21 Gems of Magic Book 50 Kute koin Tricks Book 50 Tricks With A Paper Cone Book Abbott Book of Escapes Book Anthology of Card Magic Book Art of Body Loading Book Bag O Trix Book Best of Senator Crandall Book Card Magic of the Mind Book Chinese Magic & Illusions Book Coin and Money Magic Book Comedy Tonight Book Book Eddie Joseph on Cups and Balls Book Eddie's Dumfounders -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Avengers and Its Applicability in the Swedish EFL-Classroom

Master’s Thesis Avenging the Anthropocene Green philosophy of heroes and villains in the motion picture tetralogy The Avengers and its applicability in the Swedish EFL-classroom Author: Jens Vang Supervisor: Anne Holm Examiner: Anna Thyberg Date: Spring 2019 Subject: English Level: Advanced Course code: 4ENÄ2E 2 Abstract This essay investigates the ecological values present in antagonists and protagonists in the narrative revolving the Avengers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The analysis concludes that biocentric ideals primarily are embodied by the main antagonist of the film series, whereas the protagonists mainly represent anthropocentric perspectives. Since there is a continuum between these two ideals some variations were found within the characters themselves, but philosophical conflicts related to the environment were also found within the group of the Avengers. Excerpts from the films of the study can thus be used to discuss and highlight complex ecological issues within the EFL-classroom. Keywords Ecocriticism, anthropocentrism, biocentrism, ecology, environmentalism, film, EFL, upper secondary school, Avengers, Marvel Cinematic Universe Thanks Throughout my studies at the Linneaus University of Vaxjo I have become acquainted with an incalculable number of teachers and peers whom I sincerely wish to thank gratefully. However, there are three individuals especially vital for me finally concluding my studies: My dear mother; my highly supportive girlfriend, Jenniefer; and my beloved daughter, Evie. i Vang ii Contents 1 Introduction -

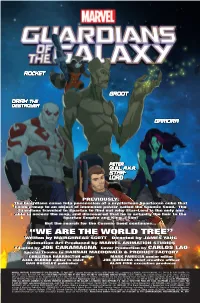

“We Are the World Tree”

PREVIOUSLY: The Guardians came into possession of a mysterious Spartaxan cube that holds a map to an object of immense power called the Cosmic Seed. The Guardians traveled to Spartax to fi nd out why Star-Lord is the only one able to access the map, and discovered that he is actually the heir to the Spartax Empire and King J’Son! But the search for the Cosmic Seed continues... “WE ARE THE WORLD TREE” Written by MAIRGHREAD SCOTT Directed by JAMES YANG Animation Art Produced by MARVEL ANIMATION STUDIOS Adapted by JOE CARAMAGNA Cover Production by CARLOS LAO Special Thanks to HANNAH MACDONALD & PRODUCT FACTORY CHRISTINA HARRINGTON editor MARK PANICCIA senior editor AXEL ALONSO editor in chief JOE QUESADA chief creative offi cer DAN BUCKLEY publisher ALAN FINE executive producer MARVEL UNIVERSE GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY No. 17, April 2017. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2017 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. $2.99 per copy in the U.S. (GST #R127032852) in the direct market; Canadian Agreement #40668537. Printed in the USA. Subscription rate (U.S. dollars) for 12 issues: U.S. $26.99; Canada $42.99; Foreign $42.99. POSTMASTER: SEND ALL ADDRESS CHANGES TO MARVEL UNIVERSE GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY, C/O MARVEL SUBSCRIPTIONS P.O. -

‗DEFINED NOT by TIME, but by MOOD': FIRST-PERSON NARRATIVES of BIPOLAR DISORDER by CHRISTINE ANDREA MUERI Submitted in Parti

‗DEFINED NOT BY TIME, BUT BY MOOD‘: FIRST-PERSON NARRATIVES OF BIPOLAR DISORDER by CHRISTINE ANDREA MUERI Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Kimberly Emmons Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August 2011 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Andrea Mueri candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree *. (signed) Kimberly K. Emmons (chair of the committee) Kurt Koenigsberger Todd Oakley Jonathan Sadowsky May 20, 2011 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 I dedicate this dissertation to Isabelle, Genevieve, and Little Man for their encouragement, unconditional love, and constant companionship, without which none of this would have been achieved. To Angie, Levi, and my parents: some small piece of this belongs to you as well. 4 Table of Contents Dedication 3 List of tables 5 List of figures 6 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 8 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: The Bipolar Story 28 Chapter 3: The Lay of the Bipolar Land 64 Chapter 4: Containing the Chaos 103 Chapter 5: Incorporating Order 136 Chapter 6: Conclusion 173 Appendix 1 191 Works Cited 194 5 List of Tables 1. Diagnostic Criteria for Manic and Depressive Episodes 28 2. Therapeutic Approaches for Treating Bipolar Disorder 30 3. List of chapters from table of contents 134 6 List of Figures 1. Bipolar narratives published by year, 2000-2010 20 2. Graph from Gene Leboy, Bipolar Expeditions 132 7 Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge my advisor, Kimberly Emmons, for her ongoing guidance and infinite patience. -

2014 Annual Report

t 2014 ANNUAL REPORT KOKUA Extending loving, sacrificial help to others IRONMANFOUNDATION.ORG IRONMANFOUNDATION.ORG TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 MISSION // 02 VISION // 03 ABOUT THE FOUNDATION // 04 GRANT SPOTLIGHTS // 11 FOUNDATION AMBASSADOR TEAM 12 YOUR JOURNEY, YOUR CAUSE // 13 KONA AUCTION // 14 PARTNERS // 15 FINANCIALS //17 DONORS // 21 OUR TEAM IRONMANFOUNDATION.ORG OUR MISSION The mission of The IRONMAN Foundation is to leave the IRONMAN legacy through philanthropy, volunteerism and grant making by supporting various athletic, community, education, health, human services and public benefit organizations around the world. OUR VISION IRONMANFOUNDATION.ORG PHILANTHROPY The IRONMAN Foundation makes a lasting impact through community funding, service and goodwill to enhance IRONMAN race communities. GIVING BACK The IRONMAN Foundation provides grant funding opportunities to local nonprofit organizations in an effort to leave the legacy of IRONMAN behind after race day. VOLUNTEERISM The IRONMAN Foundation presents several opportunities for athletes and fans to become involved and support the community. ENCOURAGE FUNDRAISING The IRONMAN Foundation makes it very easy for athletes to start fundraising campaigns through personal web pages to support a variety of non-profit organizations. ENGAGE OTHER NONPROFITS Through charity partnerships and grant funding, the IRONMAN Foundation works with and supports over 1,000 non-profit organizations every year. INSPIRE ATHLETES AND FANS The majority of athletes have a story to share about their IRONMAN journey. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J.