Brendan Lacy M.Arch Thesis.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Disaggregating the Scare from the Greens

DISAGGREGATING THE SCARE FROM THE GREENS Lee Hall*† INTRODUCTION When the Vermont Law Review graciously asked me to contribute to this Symposium focusing on the tension between national security and fundamental values, specifically for a segment on ecological and animal- related activism as “the threat of unpopular ideas,” it seemed apt to ask a basic question about the title: Why should we come to think of reverence for life or serious concern for the Earth that sustains us as “unpopular ideas”? What we really appear to be saying is that the methods used, condoned, or promoted by certain people are unpopular. So before we proceed further, intimidation should be disaggregated from respect for the environment and its living inhabitants. Two recent and high-profile law-enforcement initiatives have viewed environmental and animal-advocacy groups as threats in the United States. These initiatives are the Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) prosecution and Operation Backfire. The former prosecution targeted SHAC—a campaign to close one animal-testing firm—and referred also to the underground Animal Liberation Front (ALF).1 The latter prosecution *. Legal director of Friends of Animals, an international animal-rights organization founded in 1957. †. Lee Hall, who can be reached at [email protected], thanks Lydia Fiedler, the Vermont Law School, and Friends of Animals for making it possible to participate in the 2008 Symposium and prepare this Article for publication. 1. See Indictment at 14–16, United States v. Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty USA, Inc., No. 3:04-cr-00373-AET-2 (D.N.J. May 27, 2004), available at http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/nj/press/files/ pdffiles/shacind.pdf (last visited Apr. -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Contest/Candidate Proof List: 2016

Contest/Candidate Proof List 2016 Presidential Primary Election Contests: 1001 to 5028 - Contests On Ballot Candidates are in Random Alpha Order Candidates: Qualified Candidates Num Num Contest/District Vote For Cands Qualified Status Partisan PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES President of the US DEM 1001 President DEM, DEM *0-0 County of Sacramento 1 7 7 ON BALLOT Incumbent(s): Barack Obama Elected Candidate(s): KEITH JUDD Qualified Date: 3/11/2016 No Ballot Designation User Codes: Cand ID: 4 Filing Fee: $0.00 Fees Paid: $0.00 $0.00 Requirements Status ------------------------------------------------------- Sigs In Lieu Issued Sigs In Lieu Filed Declaration of Intent Issued Declaration of Intent Filed Candidate Statement Issued Candidate Statement Filed Declaration of Candidacy Issued Declaration of Candidacy Filed Code of Fair Campaign Practices Filed Ballot Designation Worksheet Issued Ballot Designation Worksheet Filed MICHAEL STEINBERG Qualified Date: 3/11/2016 No Ballot Designation User Codes: Cand ID: 6 Filing Fee: $0.00 Fees Paid: $0.00 $0.00 Requirements Status ------------------------------------------------------- Sigs In Lieu Issued Sigs In Lieu Filed Declaration of Intent Issued Declaration of Intent Filed Candidate Statement Issued Candidate Statement Filed Declaration of Candidacy Issued Declaration of Candidacy Filed Code of Fair Campaign Practices Filed Ballot Designation Worksheet Issued Ballot Designation Worksheet Filed BERNIE SANDERS Qualified Date: 3/11/2016 No Ballot Designation User Codes: Cand ID: 5 Filing Fee: $0.00 -

Simonson's Thor Bronze Age Thor New Gods • Eternals

201 1 December .53 No 5 SIMONSON’S THOR $ 8 . 9 BRONZE AGE THOR NEW GODS • ETERNALS “PRO2PRO” interview with DeFALCO & FRENZ HERCULES • MOONDRAGON exclusive MOORCOCK interview! 1 1 1 82658 27762 8 Volume 1, Number 53 December 2011 Celebrating The Retro Comics Experience! the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks . COVER ARTIST c n I , s Walter Simonson r e t c a r a COVER COLORIST h C l Glenn Whitmore e v r a BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 M COVER DESIGNERS 1 1 0 2 Michael Kronenberg and John Morrow FLASHBACK: The Old Order Changeth! Thor in the Early Bronze Age . .3 © . Stan Lee, Roy Thomas, and Gerry Conway remember their time in Asgard s n o i PROOFREADER t c u OFF MY CHEST: Three Ways to End the New Gods Saga . .11 A Rob Smentek s c The Eternals, Captain Victory, and Hunger Dogs—how Jack Kirby’s gods continued with i m SPECIAL THANKS o C and without the King e g Jack Abramowitz Brian K. Morris a t i r FLASHBACK: Moondragon: Goddess in Her Own Mind . .19 e Matt Adler Luigi Novi H f Getting inside the head of this Avenger/Defender o Roger Ash Alan J. Porter y s e t Bob Budiansky Jason Shayer r FLASHBACK: The Tapestry of Walter Simonson’s Thor . .25 u o C Sal Buscema Walter Simonson Nearly 30 years later, we’re still talking about Simonson’s Thor —and the visionary and . -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

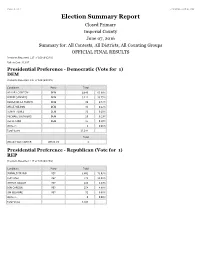

Election Summary Report

Page: 1 of 7 7/1/2016 4:20:45 PM Election Summary Report Closed Primary Imperial County June 07, 2016 Summary for: All Contests, All Districts, All Counting Groups OFFICIAL FINAL RESULTS Precincts Reported: 117 of 169 (69.23%) Ballots Cast: 23,897 Presidential Preference - Democratic (Vote for 1) DEM Precincts Reported: 117 of 169 (69.23%) Candidate Party Total HILLARY CLINTON DEM 9,843 65.00% BERNIE SANDERS DEM 5,111 33.75% ROQUE DE LA FUENTE DEM 80 0.53% WILLIE WILSON DEM 34 0.22% HENRY HEWES DEM 31 0.20% MICHAEL STEINBERG DEM 29 0.19% KEITH JUDD DEM 15 0.10% Write-in 1 0.01% Total Votes 15,144 Total WILLIE FELIX CARTER WRITE-IN 1 Presidential Preference - Republican (Vote for 1) REP Precincts Reported: 117 of 169 (69.23%) Candidate Party Total DONALD TRUMP REP 3,801 73.03% TED CRUZ REP 771 14.81% JOHN R. KASICH REP 348 6.69% BEN CARSON REP 254 4.88% JIM GILMORE REP 31 0.60% Write-in 0 0.00% Total Votes 5,205 Page: 2 of 7 7/1/2016 4:20:45 PM Presidential Preference - American Independent (Vote for 1) AI Precincts Reported: 117 of 169 (69.23%) Candidate Party Total ROBERT ORNELAS AI 55 38.19% ALAN SPEARS AI 22 15.28% J.R. MYERS AI 22 15.28% ARTHUR HARRIS AI 15 10.42% JAMES HEDGES AI 13 9.03% WILEY DRAKE AI 11 7.64% THOMAS HOEFLING AI 6 4.17% Write-in 0 0.00% Total Votes 144 Presidential Preference - Green (Vote for 1) GRN Precincts Reported: 117 of 169 (69.23%) Candidate Party Total JILL STEIN GRN 9 60.00% DARRYL CHERNEY GRN 4 26.67% WILLIAM KREML GRN 2 13.33% KENT MESPLAY GRN 0 0.00% SEDINAM MOYOWASIFSA- GRN 0 0.00% CURRY Write-in 0 0.00% Total Votes 15 Presidential Preference - Libertarian (Vote for 1) LIB Precincts Reported: 117 of 169 (69.23%) Candidate Party Total GARY JOHNSON LIB 34 55.74% AUSTIN PETERSEN LIB 7 11.48% RHETT WHITE FEATHER LIB 4 6.56% SMITH JOY WAYMIRE LIB 3 4.92% STEVE KERBEL LIB 3 4.92% DARRYL W. -

Presidential Primary

PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY, MARCH 1, 2016 Town of Hanson Precinct I Precinct II Precinct III Total DEMOCRATIC PARTY PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE Bernie Sanders 319 335 343 997 Martin O'Malley 3 2 0 5 Hillary Clinton 240 256 196 692 Rdoque "Rocky" De La Fuente 0 1 0 1 No Preference 4 7 3 14 Write Ins (all others) 5 2 0 7 Blanks 4 2 2 8 STATE COMMITTEE MAN 2nd Plymouth & Bristol District Michael D. Brady 382 421 355 1158 Tony Branch 53 54 71 178 Write Ins (all others) 1 0 0 1 Blanks 139 130 118 387 STATE COMMITTEE WOMAN 2nd Plymouth & Bristol District Write Ins (all others) 7 4 9 20 Susan W. Robinson 2 0 0 2 Jenna L. Powers 1 0 0 1 Vinessa A. Mihos 1 0 0 1 Kathleen DiPasqua Egan 2 0 0 2 Margaret M. O'Connor 1 0 0 1 Linda S. Christensen 1 0 0 1 Barabra M. Ferguson 1 0 0 1 Kristen Ann Kames 0 1 0 1 Sandra L.Wilson 0 1 0 1 Laura A Fitzgerald-Kemmett 0 0 1 1 Kathleen A. Nee 0 0 1 1 Amber Marie Watson 0 0 1 1 Blanks 559 599 532 1690 PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY, MARCH 1, 2016 Town of Hanson Precinct I Precinct II Precinct III Total TOWN COMMITTEE-35 to be elected Patrick M. O'Connor 252 263 231 746 Kathleen DiPasqua-Egan 250 277 264 791 James A. Egan 274 290 263 827 Joseph A. O'Sullivan 270 282 237 789 Thomas McSweeney 244 271 232 747 Stephanie A. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

ABSTRACT the Pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group Warrant Serious Consideration As .A Legitimate Narrative Enterprise

DOCU§ENT RESUME ED 190 980 CS 005 088 AOTHOR Palumbo, Don'ald TITLE The use of, Comics as an Approach to Introducing the Techniques and Terms of Narrative to Novice Readers. PUB DATE Oct 79 NOTE 41p.: Paper' presented at the Annual Meeting of the Popular Culture Association in the South oth, Louisville, KY, October 18-20, 19791. EDFS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage." DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature:,*Comics (Publications) : *Critical Aeading: *English Instruction: Fiction: *Literary Criticism: *Literary Devices: *Narration: Secondary, Educition: Teaching Methods ABSTRACT The pdblications of the Marvel Comics Group warrant serious consIderation as .a legitimate narrative enterprise. While it is obvious. that these comic books can be used in the classroom as a source of reading material, it is tot so obvious that these comic books, with great economy, simplicity, and narrative density, can be used to further introduce novice readers to the techniques found in narrative and to the terms employed in the study and discussion of a narrative. The output of the Marvel Conics Group in particular is literate, is both narratively and pbSlosophically sophisticated, and is ethically and morally responsible. Some of the narrative tecbntques found in the stories, such as the Spider-Man episodes, include foreshadowing, a dramatic fiction narrator, flashback, irony, symbolism, metaphor, Biblical and historical allusions, and mythological allusions.4MKM1 4 4 *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** ) U SOEPANTMENTO, HEALD.. TOUCATiONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE CIF 4 EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT was BEEN N ENO°. DOCEO EXACTLY AS .ReCeIVED FROM Donald Palumbo THE PE aSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGuN- ATING T POINTS VIEW OR OPINIONS Department of English STATED 60 NOT NECESSARILY REPRf SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF O Northern Michigan University EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY CO Marquette, MI. -

Annual Report July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015

Annual Report July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–2012 1 Preserving America’s Past Since 1791 Board of Trustees 2015 Officers Trustees Life Trustees Charles C. Ames, Chair Benjamin C. Adams Bernard Bailyn A Message from the Chair of the Board & the President Nancy S. Anthony, Oliver Ames Leo Leroy Beranek Vice Chair Frederick D. Ballou Levin H. Campbell, Sr. In FY2015 the Society’s quest to promote the value and importance of our country’s Frederick G. Pfannenstiehl, Levin H. Campbell, Jr. Henry Lee past reached new heights. Vice Chair Joyce E. Chaplin Trustees Emeriti Programming was at the forefront as we sought a larger, more diverse following. Judith Bryant Wittenberg, William C. Clendaniel Nancy R. Coolidge Our conference, “So Sudden an Alteration”: The Causes, Course, and Consequences of Secretary Herbert P. Dane Arthur C. Hodges the American Revolution, was a centerpiece. The largest scholarly conference we have William R. Cotter, Amalie M. Kass James M. Storey ever presented, it stimulated passionate, meaningful discussion and received wide praise. Accompanying this gathering was the exhibition God Save the People! From the Treasurer Anthony H. Leness John L. Thorndike Stamp Act to Bunker Hill, which focused on the prelude to the American Revolution. G. Marshall Moriarty Hiller B. Zobel Lisa B. Nurme This was just one of the highlights of a year during which the MHS offered over 110 Lia G. Poorvu public programs on topics as diverse as the Confederate raid of St. Albans, Vermont, Byron Rushing the first flight to the North Pole, and colonial New England’s potent potables.