Assam's Pig Subsector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED for the POST of GD. IV of AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT of DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR

LIST OF ACCEPTED CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR THE POST OF GD. IV OF AMALGAMATED ESTABLISHMENT OF DEPUTY COMMISSIONER's, LAKHIMPUR Date of form Sl Post Registration No Candidate Name Father's Name Present Address Mobile No Date of Birth Submission 1 Grade IV 101321 RATUL BORAH NAREN BORAH VILL:-BORPATHAR NO-1,NARAYANPUR,GOSAIBARI,LAKHIMPUR,Assam,787033 6000682491 30-09-1978 18-11-2020 2 Grade IV 101739 YASHMINA HUSSAIN MUZIBUL HUSSAIN WARD NO-14, TOWN BANTOW,NORTH LAKHIMPUR,KHELMATI,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 6002014868 08-07-1997 01-12-2020 3 Grade IV 102050 RAHUL LAMA BIKASH LAMA 191,VILL NO 2 DOLABARI,KALIABHOMORA,SONITPUR,ASSAM,784001 9678122171 01-10-1999 26-11-2020 4 Grade IV 102187 NIRUPAM NATH NIDHU BHUSAN NATH 98,MONTALI,MAHISHASAN,KARIMGANJ,ASSAM,788781 9854532604 03-01-2000 29-11-2020 5 Grade IV 102253 LAKHYA JYOTI HAZARIKA JATIN HAZARIKA NH-15,BRAHMAJAN,BRAHMAJAN,BISWANATH,ASSAM,784172 8638045134 26-10-1991 06-12-2020 6 Grade IV 102458 NABAJIT SAIKIA LATE CENIRAM SAIKIA PANIGAON,PANIGAON,PANIGAON,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787052 9127451770 31-12-1994 07-12-2020 7 Grade IV 102516 BABY MISSONG TANKESWAR MISSONG KAITONG,KAITONG ,KAITONG,DHEMAJI,ASSAM,787058 6001247428 04-10-2001 05-12-2020 8 Grade IV 103091 MADHYA MONI SAIKIA BOLURAM SAIKIA Near Gosaipukhuri Namghor,Gosaipukhuri,Adi alengi,Lakhimpur,Assam,787054 8011440485 01-01-1987 07-12-2020 9 Grade IV 103220 JAHAN IDRISH AHMED MUKSHED ALI HAZARIKA K B ROAD,KHUTAKATIA,JAPISAJIA,LAKHIMPUR,ASSAM,787031 7002409259 01-01-1988 01-12-2020 10 Grade IV 103270 NIHARIKA KALITA ARABINDA KALITA 006,GUWAHATI,KAHILIPARA,KAMRUP -

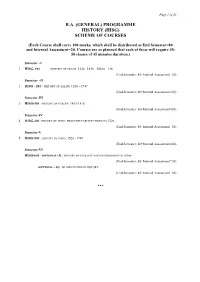

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Goalpariya Language a Brief Study

GOALPARIYA LANGUAGE A BRIEF STUDY By Dr. Mir Jahan Ali Prodhani M.A.(Triple), PGDTE(CIEFL), Ph.D. Asstt. Prof., Dept. of English B.N.College, Dhubri (Assam) NINAD GOSTI GAUHATI UNIVERSITY CAMPUS GUWAHATI-14 GOALPARIYA LANGUAGE : A BRIEF STUDY is a synchronic study by Dr. Mir Jahan Ali Prodhani based on his knowledge as a native speaker of the language and the information collected by him as the investigator of an MRP on Goalpariya Language: A Synchronic Study financed by the UGC during the financial year 2009-10. Published by NINAD GOSTI GAUHATI UNIVERSITY CAMPUS GUWAHATI-14 © The author Price: Rs. 50.00 First Edition: July, 2010 DECLARATION This is to declare that this book represents my own original work, except for the materials gathered from scholarly writings and guidance required from the experts, retired teachers, parents and all other sources, acknowledged appropriately in the book. In connection with the phonetic transcription, I further declare that I have followed the system adopted by “THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY” rather than the I.P.A. in order to avoid certain inconveniences. - The Writer ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I sincerely acknowledge the help and guidance of Dr. K. G. Vijayakrishnan, Head of the Department of Linguistics & Contemporary English, CIEFL, Hyderabad-7, Dr. Dilip Borah, Reader, Department of M.I.L., G.U. and Sri G. S. Pande, Ex- Principal of P. B. College, Gauripur in writing this book. I also acknowledge the help and co-operation of all the lecturers in the Department of English of B. N. college, Dhubri without which it would have not been possible for me to collect the huge amount of data and information required for this book. -

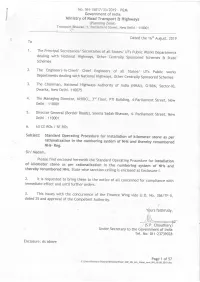

Chief Engineers of At{ States/ Uts Pubtic Works Subject: Stand

p&M n No. NH- 1501 7 / 33 t2A19 - lllnt r Govennment of India $ Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (Ptanning Zone) Transport Bhawan, 1, Partiarnent street, I.{ew Dethi - 110001 Dated the 16th August, 2019 To 1. The PrincipaL secretaries/ secretaries of atl states/ UTs Pubtic Works Departments dealing with National Highways, other centratty Sponsored Schemes & State Schemes 2. Engineers-in-Chief/ The Chief Engineers of at{ States/ UTs pubtic works Departments deating with National Highways, Other Centpatty Sponsored Schemes 3. The Chairman, Nationa[ Highways Authority of India (NHAI), G-5&6, Sector-10, Dwarka, New Dethi- 1rc075 4. The Managing Director, NHIDCL, 3'd Floor, PTI Buitding, 4-parliament Street, New Dethi - 110001 5. Director General (Border Roads), Seema Sadak Bhawan, 4- partiament Street, New Dethi - 1 10001 6. Att CE ROs / SE ROs Subject: Standard Operating Procedure for installation of kilometer stone as per rationalization in the numbering system of NHs and thereby renumbered NHs- Reg. Sir/ Madam, Ptease find enctosed herewith the Standard Operating Procedure for installation of kilometer stone as per rationalization in the numbering system of NHs and thereby renumbered NHs. State wise sanction ceiting is enclosed at Enclosure-;. is 2' lt requested to bring these to the notice of att concerned for comptiance with immediate effect and untiI further orders. 3- This issues with the concurrence of the Finance wing vide u.o. No. 356/TF-ll, dated 25 and approvat of the competent Authority. rs faithfulty, (5.P. Choudhary) Under Secretary to the rnment of India Tet. No. 01 1-23n9A28 f,nctosure: As above Page 1 of 57 c:\users\Hemont Dfiawan\ Desktop\Finat_sop_NH_km*stone*new_l.JH_ l6.0g.2019.doc - No. -

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj This PDF file contains the complete book of the Serpent Power as listed below. 1) THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER By WOODROFFE. 2) Ṣaṭ-Cakra-Nirūpaṇa, Six-Cakra Investigation: Description of and Investigation into the Six Bodily Centers by Tantrik Purnananda-Svami (1526 CE). 3) THE FIVEFOLD FOOTSTOOL (PĀDUKĀ-PAÑCAKA THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER See the diagram in the next page. INTRODUCTION PAGE 1 THE two Sanskrit works here translated---Ṣat-cakra-nirūpaṇa (" Description of the Six Centres, or Cakras") and Pādukāpañcaka (" Fivefold footstool ")-deal with a particular form of Tantrik Yoga named Kuṇḍalinī -Yoga or, as some works call it, Bhūta-śuddhi, These names refer to the Kuṇḍalinī-Śakti, or Supreme Power in the human body by the arousing of which the Yoga is achieved, and to the purification of the Elements of the body (Bhūta-śuddhi) which takes place upon that event. This Yoga is effected by a process technically known as Ṣat-cakra-bheda, or piercing of the Six Centres or Regions (Cakra) or Lotuses (Padma) of the body (which the work describes) by the agency of Kuṇḍalinī- Sakti, which, in order to give it an English name, I have here called the Serpent Power.1 Kuṇḍala means coiled. The power is the Goddess (Devī) Kuṇḍalinī, or that which is coiled; for Her form is that of a coiled and sleeping serpent in the lowest bodily centre, at the base of the spinal column, until by the means described She is aroused in that Yoga which is named after Her. -

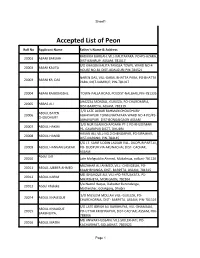

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY of the REGION Ahom

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY OF THE REGION Ahom and Assam are inter-related terms. The word Ahom means the SHAN or the TAI people who migrated to the Brahma putra valley in the 13th Century A.D. from their original homeland MUNGMAN or PONG situated in upper Bunna on the Irrawaddy river. The word Assam refers to the Brahmaputra valley and the adjoining areas where the Shan people settled down and formed a kingdom with the intention of permanently absorbing in the land and its heritage. From the prehistoric period to about 13th/l4 Century A.D. Assam was referred to as Kamarupa and Pragjyotisha in Indian literary works and historical accounts. Early Period ; Area and Jurisdiction In the Ramayana and Mahabharata and in the Puranik and Tantrik literature, there are numerous references to ancient Assam, which was known as Pragjyotisha in the epics and Kamarupa in the Puranas and Tantras. V^Tien the stories related to it inserted in the Maha bharata, it stretched southward as far as the Bay of Bengal and its western boundary was river Karotoya. This was then a river of the first order and united in its bed the streams which now form the Tista, the Kosi and the Mahanada.^ 14 15 According to the most of the Puranas dealing with geo graphy of the earlier period, the kingdom extended upto the river Karatoya in the west and included Manipur, Jayantia, Cachar, parts of Mymensing, Sylhet, Rangpur and portions of 2 Bhutan and Nepal. The Yogini Yantra (V I:16-18) describes the boundary as - Nepalasya Kancanadrin Bramaputrasye Samagamam Karotoyam Samarabhya Yavad Dipparavasinara Uttarasyam Kanjagirah Karatoyatu pascime tirtharestha Diksunadi Purvasyam giri Kanyake Daksine Brahmaputrasya Laksayan Samgamavadhih Kamarupa iti Khyatah Sarva Sastresu niscitah. -

WHO Country Office in India SITUATION REPORT—ASSAM FLOODS, NORTH INDIA

WHO Country Office in India SITUATION REPORT—ASSAM FLOODS, NORTH INDIA NAME OF THE DISASTER: FLOODS DATE: 12.07.04 The state of Assam is experiencing its first phase of floods due to the incessant rains since the last week of June over Assam and the neighboring country Bhutan and states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, & Nagaland. From a total of 28 districts, so far 23 districts have been affected. The districts are Tinsukia, Dibrugarh, Shivsagar, Jorhat, Golaghat, Nagoan, Morigaon, Kamrup, Kamrup Metro, Darrang, Sonitpur, Dhemaji, Lakhimpur, Nalbari, Berpetta, Bongaigaon, Kokrajhar, Goalpara, Dhubri, Chirang, Karbi Anglong, Karimganj and Hailakhandi. Kamrup, Nalbari, Darrang, Sonitpur, Dhemaji and Lakhimpur are the most affected districts. This flood has caused widespread damage to human life and property, standing crops, flood control embankments and basic infrastructure. CURRENT SITUATION: • A vast area of human habitation is under water in the affected districts and people have taken shelter on the embankments. • 2,794 villages have so far been affected by the first phase of floods this year, affecting a population of 2 million (5 lakhs) approximately. • Damage to homes is significant, with approximately 14,320 houses washed away and 25,000 houses partially damaged. • The official estimate of loss of human lives is 13 to date. • The total crop area affected is estimated to be 4 lakh hectares. • Altogether, 58 breaches of embankment have taken place since April 2004, of which 24 major breaches have taken place during the month of July 2004. There is a threat of a few more fresh breaches on the embankment of the Brahmaputra river and its tributaries as the water level continues to rise. -

Revenue and Fiscal Regulation of the Ahoms Dr. Meghali Bora

Social Science Journal of Gargaon College, Volume V • January, 2017 ISSN 2320-0138 Revenue and Fiscal Regulation of The Ahoms *Dr. Meghali Bora Abstract The Ahom kings who ruled over Assam for six hundred years left their indelible contributions not only on the life and culture of the people but also tried their best to improve the economy of the state by maintaining a rigid and peculiar system of revenue administration. For proper functioning of revenue and fiscal administration the Ahom kings introduced well knitted paik and khel system which was the backbone of the Ahom economy. The Ahom kings also received a good amount of revenue by collecting different kinds of taxes from hats, ghats, phats, beels, chokis and tributes from subordinates chiefs and kingdoms. It was only because of having such affluent economy the Ahoms could rule in Assam for about six hundred years. Key words : Revenue administration, Paik and Khel system and Trade statistics. Introduction : In the beginning of the Ahom reign there was no clear cut policy on civil and revenue administration. The first step towards the creation of a separate revenue department was taken by Pratap Singha (1603-41) who created the posts of Barbarua and Barphukon. The Barbarua was the chief executive revenue and judicial officer of Upper Assam and the Barphukan posted at Guwahati was of Lower Assam. Later king Rudra Singha (1696-1714) completed the process of revenue administration by creating two central revenue departments, one at Rangpur (Upper Assam) and another at Guwahati (Lower Assam). There were three main sources from which the Ahom kings collected their revenue and these were personal service, produce of the land and cash. -

Empire's Garden: Assam and the Making of India

A book in the series Radical Perspectives a radical history review book series Series editors: Daniel J. Walkowitz, New York University Barbara Weinstein, New York University History, as radical historians have long observed, cannot be severed from authorial subjectivity, indeed from politics. Political concerns animate the questions we ask, the subjects on which we write. For over thirty years the Radical History Review has led in nurturing and advancing politically engaged historical research. Radical Perspec- tives seeks to further the journal’s mission: any author wishing to be in the series makes a self-conscious decision to associate her or his work with a radical perspective. To be sure, many of us are currently struggling with the issue of what it means to be a radical historian in the early twenty-first century, and this series is intended to provide some signposts for what we would judge to be radical history. It will o√er innovative ways of telling stories from multiple perspectives; comparative, transnational, and global histories that transcend con- ventional boundaries of region and nation; works that elaborate on the implications of the postcolonial move to ‘‘provincialize Eu- rope’’; studies of the public in and of the past, including those that consider the commodification of the past; histories that explore the intersection of identities such as gender, race, class and sexuality with an eye to their political implications and complications. Above all, this book series seeks to create an important intellectual space and discursive community to explore the very issue of what con- stitutes radical history. Within this context, some of the books pub- lished in the series may privilege alternative and oppositional politi- cal cultures, but all will be concerned with the way power is con- stituted, contested, used, and abused. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

Survey of District Libraries in Lower Assam Pjaee, 17 (6) (2020)

SURVEY OF DISTRICT LIBRARIES IN LOWER ASSAM PJAEE, 17 (6) (2020) SURVEY OF DISTRICT LIBRARIES IN LOWER ASSAM Kankana Chakraborty MLISc., Gauhati University, Ghy- 14 E-mail ID: [email protected] Kankana Chakraborty: Survey of District Libraries in Lower Assam-- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(6). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Public Library, District Library, Rural Library, Information provider, Rural development. ABSTRACT The main purpose of this paper is to give an overview of the public library system in Assam. The present scenario of the district libraries of Assam also included in this paper. For the survey, there are total three districts are selected from lower Assam. And the interview method is used to collect relevant data from the library professionals. Various primary and secondary literatures are also studied to gain the knowledge about public library system in Assam. The finding of the study reveals that the condition of the district libraries of Assam is not very impressive. Though these three public libraries are rich in regard to their collection and staff, but the number of daily users of the district libraries is not as par the expectation. And most of users visit the library for reading newspapers. The finding also shows that due to the lack of the funds as well as government initiative the libraries are not fulfill the requirements of the users of the libraries. One more important finding is that the libraries are lacking behind in terms of using modern technologies like computer and internet etc. which becomes a basic need of today’s generation.