MORE on “KAMARUPAN” Robbins Burling University of Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

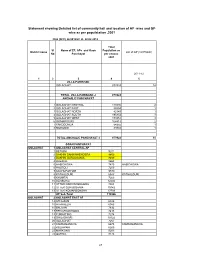

Golaghat ZP-F

Statement showing Detailed list of community hall and location of AP -wise and GP- wise as per populatation ,2001 FEA (SFC) 26/2012/41 dt. 28.02.2012 Total Sl Name of ZP, APs and Gaon Population as District name List of GP (1st Phash) No Panchayat per census 2001 2011-12 12 3 4 5 ZILLA PARISHAD GOLAGHAT 873924 14 TOTAL ZILLA PARISHAD -I 873924 ANCHALIC PANCHAYAT 1 GOLAGHAT CENTRAL 118546 2 2 GOLAGHAT EAST 88554 1 3 GOLAGHAT NORTH 42349 1 4 GOLAGHAT SOUTH 195854 3 5 GOLAGHAT WEST 179451 3 6 GOMARIGURI 104413 2 7 KAKODONGA 54955 1 8 MORONGI 89802 1 TOTAL ANCHALIC PANCHAYAT -I 873924 14 GOAN PANCHAYAT GOLAGHAT 1 GOLAGHAT CENTRAL AP 1 BETIONI 9201 2 DAKHIN DAKHINHENGERA 9859 3 DAKHIN GURJOGANIA 8457 4 DHEKIAL 8663 5 HABICHOWA 7479 HABICHOWA 6 HAUTOLI 7200 7 KACHUPATHAR 9579 8 KATHALGURI 6543 KATHALGURI 9 KHUMTAI 7269 10 SENSOWA 12492 11 UTTER DAKHINHENGERA 7864 12 UTTER GURJOGANIA 10142 13 UTTER KOMARBONDHA 13798 AP Sub-Total 118546 GOLAGHAT 2 GOLAGHAT EAST AP 14 ATHGAON 6426 15 ATHKHELIA 6983 16 BALIJAN 7892 17 BENGENAKHOWA 7418 18 FURKATING 7274 19 GHILADHARI 10122 20 GOLAGHAT 7257 21 KAMARBANDHA 6678 KAMARBANDHA 22 KOLIAPANI 6265 23 MARKONG 5203 24 OATING 8128 23 12 3 4 5 25 PULIBOR 8908 AP Sub-Total 88554 GOLAGHAT 3 GOLAGHAT NORTH AP 26 MADHYA BRAHMAPUTRA 8091 27 MADHYA MISAMORA 7548 28 PACHIM BRAHMAPUTRA 8895 PACHIM BRAHMAPUTRA 29 PACHIM MISAMORA 8382 30 PUB MISAMORA 9433 AP Sub-Total 42349 GOLAGHAT 4 GOLAGHAT SOUTH AP 31 CHUNGAJAN 13943 32 CHUNGAJAN MAZGAON 5923 33 CHUNGAJAN MIKIR VILLAGES 7401 34 GANDHKOROI 10847 35 GELABIL 12224 36 -

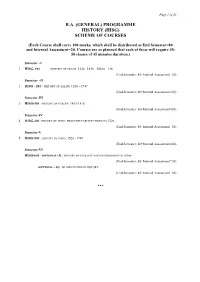

The Proposed New Syllabus of History for the B

Page 1 of 45 B.A. (GENERAL) PROGRAMME HISTORY (HISG) SCHEME OF COURSES (Each Course shall carry 100 marks, which shall be distributed as End Semester=80 and Internal Assessment=20. Courses are so planned that each of these will require 45- 50 classes of 45 minutes duration.) Semester –I 1. HISG- 101 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 – Marks= 100 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester –II 2. HISG - 201 : HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1826 – 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-III 3. HISG-301 : HISTORY OF EUROPE: 1453-1815 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-IV 4. HISG-401: HISTORY OF INDIA FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO 1526 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-V 5. HISG-501 : HISTORY OF INDIA: 1526 - 1947 (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) Semester-VI HISG-601 : (OPTIONAL - I) : HISTORY OF ECOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENT IN INDIA (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) (OPTIONAL – II) : WOMEN IN INDIAN HISTORY (End Semester: 80+Internal Assessment=20) *** Page 2 of 45 HISG – 101 End- Semester Marks : 80 In- Semester Marks : 20 HISTORY OF ASSAM: 1228 –1826 Total Marks : 100 10 to 12 classes per unit Objective: The objective of this paper is to give a general outline of the history of Assam from the 13th century to the occupation of Assam by the English East India Company in the first quarter of the 19th century. It aims to acquaint the students with the major stages of developments in the political, social and cultural history of the state during the medieval times. Unit-1: Marks: 16 1.01 : Sources- archaeological, epigraphic, literary, numismatic and accounts of the foreign travelers 1.02 : Political conditions of the Brahmaputra valley at the time of foundation of the Ahom kingdom. -

Positioning of Assam As a Culturally Rich Destination: Potentialities and Prospects

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue 3 Ser. IV || Mar, 2020 || PP 34-37 Positioning Of Assam as a Culturally Rich Destination: Potentialities and Prospects Deepjoonalee Bhuyan ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 22-03-2020 Date of Acceptance: 08-04-2020 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. INTRODUCTION Cultural tourism has a special place in India because of its past civilisation. Among the various motivating factors governing travel in India, cultural tourism is undoubtedly the most important. For any foreigner, a visit to India must have a profound cultural impact and in its broader sense, tourism in India involves quite a large content of cultural content. It also plays a major role in increasing national as well as international good will and understanding. Thousands of archaeological and historical movements scattered throughout the country provide opportunites to learn about the ancient history and culture. India has been abundantly rich in its cultural heritage. Indian arts and crafts, music and dance, fairs and festivals, agriculture and forestry, astronomy and astrology, trade and transport, recreation and communication, monumental heritage, fauna and flora in wildlife and religion play a vital role in this type of tourism. Thus, it can be very well said that there remains a lot of potential for the progress of cultural tourism in India. Culturally, North East represents the Indian ethos of „unity in diversity‟ and „diversity in unity‟. It is a mini India where diverse ethnic and cultural groups of Aryans, Dravidians, Indo-Burmese, Indo Tibetan and other races have lived together since time immemorial. -

Marginalisation, Revolt and Adaptation: on Changing the Mayamara Tradition*

Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 15 (1): 85–102 DOI: 10.2478/jef-2021-0006 MARGINALISATION, REVOLT AND ADAPTATION: ON CHANGING THE MAYAMARA TRADITION* BABURAM SAIKIA PhD Student Department of Estonian and Comparative Folklore University of Tartu Ülikooli 16, 51003, Tartu, Estonia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Assam is a land of complex history and folklore situated in North East India where religious beliefs, both institutional and vernacular, are part and parcel of lived folk cultures. Amid the domination and growth of Goddess worshiping cults (sakta) in Assam, the sattra unit of religious and socio-cultural institutions came into being as a result of the neo-Vaishnava movement led by Sankaradeva (1449–1568) and his chief disciple Madhavadeva (1489–1596). Kalasamhati is one among the four basic religious sects of the sattras, spread mainly among the subdued communi- ties in Assam. Mayamara could be considered a subsect under Kalasamhati. Ani- ruddhadeva (1553–1626) preached the Mayamara doctrine among his devotees on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river. Later his inclusive religious behaviour and magical skill influenced many locals to convert to the Mayamara faith. Ritu- alistic features are a very significant part of Mayamara devotee’s lives. Among the locals there are some narrative variations and disputes about stories and terminol- ogies of the tradition. Adaptations of religious elements in their faith from Indig- enous sources have led to the question of their recognition in the mainstream neo- Vaishnava order. In the context of Mayamara tradition, the connection between folklore and history is very much intertwined. Therefore, this paper focuses on marginalisation, revolt in the community and narrative interpretation on the basis of folkloristic and historical groundings. -

LIST of POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION and RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME ZONE CODE Search

LIST OF POST GST COMMISSIONERATE, DIVISION AND RANGE USER DETAILS ZONE NAME GUW ZONE CODE 70 Search: Commission Commissionerate Code Commissionerate Jurisdiction Division Code Division Name Division Jurisdiction Range Code Range Name Range Jurisdiction erate Name Districts of Kamrup (Metro), Kamrup (Rural), Baksa, Kokrajhar, Bongaigon, Chirang, Barapeta, Dhubri, South Salmara- Entire District of Barpeta, Baksa, Nalbari, Mankachar, Nalbari, Goalpara, Morigaon, Kamrup (Rural) and part of Kamrup (Metro) Nagoan, Hojai, East KarbiAnglong, West [Areas under Paltan Bazar PS, Latasil PS, Karbi Anglong, Dima Hasao, Cachar, Panbazar PS, Fatasil Ambari PS, Areas under Panbazar PS, Paltanbazar PS & Hailakandi and Karimganj in the state of Bharalumukh PS, Jalukbari PS, Azara PS & Latasil PS of Kamrup (Metro) District of UQ Guwahati Assam. UQ01 Guwahati-I Gorchuk PS] in the State of Assam UQ0101 I-A Assam Areas under Fatasil Ambari PS, UQ0102 I-B Bharalumukh PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Gorchuk, Jalukbari & Azara PS UQ0103 I-C of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Nagarbera PS, Boko PS, Palashbari PS & Chaygaon PS of Kamrup UQ0104 I-D District Areas under Hajo PS, Kaya PS & Sualkuchi UQ0105 I-E PS of Kamrup District Areas under Baihata PS, Kamalpur PS and UQ0106 I-F Rangiya PS of Kamrup District Areas under entire Nalbari District & Baksa UQ0107 Nalbari District UQ0108 Barpeta Areas under Barpeta District Part of Kamrup (Metro) [other than the areas covered under Guwahati-I Division], Morigaon, Nagaon, Hojai, East Karbi Anglong, West Karbi Anglong District in the Areas under Chandmari & Bhangagarh PS of UQ02 Guwahati-II State of Assam UQ0201 II-A Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Noonmati & Geetanagar PS of UQ0202 II-B Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Pragjyotishpur PS, Satgaon PS UQ0203 II-C & Sasal PS of Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Dispur PS & Hatigaon PS of UQ0204 II-D Kamrup (Metro) District Areas under Basistha PS, Sonapur PS & UQ0205 II-E Khetri PS of Kamrup (Metropolitan) District. -

1 Mapping Monastic Geographicity Or Appeasing Ghosts of Monastic Subjects Indrani Chatterjee

1 Mapping Monastic Geographicity Or Appeasing Ghosts of Monastic Subjects Indrani Chatterjee Rarely do the same apparitions inhabit the work of modern theorists of subjectivity, politics, ethnicity, the Sanskrit cosmopolis and medieval architecture at once. However, the South Asianist historian who ponders the work of Charles Taylor, Partha Chatterjee, James Scott and Sheldon Pollock cannot help notice the apparitions of monastic subjects within each. Tamara Sears has gestured at the same apparitions by pointing to the neglected study of monasteries (mathas) associated with Saiva temples.1 She finds the omission intriguing on two counts. First, these monasteries were built for and by significant teachers (gurus) who were identified as repositories of vast ritual, medical and spiritual knowledge, guides to their practice and over time, themselves manifestations of divinity and vehicles of human liberation from the bondage of life and suffering. Second, these monasteries were not studied even though some of these had existed into the early twentieth century. Sears implies that two processes have occurred simultaneously. Both are epistemological. One has resulted in a continuity of colonial- postcolonial politics of recognition. The identification of a site as ‘religious’ rested on the identification of a building as a temple or a mosque. Residential sites inhabited by religious figures did not qualify for preservation. The second is the foreshortening of scholarly horizons by disappeared buildings. Modern scholars, this suggests, can only study entities and relationships contemporaneous with them and perceptible to the senses, omitting those that evade such perception or have disappeared long ago. This is not as disheartening as one might fear. -

Goalpariya Language a Brief Study

GOALPARIYA LANGUAGE A BRIEF STUDY By Dr. Mir Jahan Ali Prodhani M.A.(Triple), PGDTE(CIEFL), Ph.D. Asstt. Prof., Dept. of English B.N.College, Dhubri (Assam) NINAD GOSTI GAUHATI UNIVERSITY CAMPUS GUWAHATI-14 GOALPARIYA LANGUAGE : A BRIEF STUDY is a synchronic study by Dr. Mir Jahan Ali Prodhani based on his knowledge as a native speaker of the language and the information collected by him as the investigator of an MRP on Goalpariya Language: A Synchronic Study financed by the UGC during the financial year 2009-10. Published by NINAD GOSTI GAUHATI UNIVERSITY CAMPUS GUWAHATI-14 © The author Price: Rs. 50.00 First Edition: July, 2010 DECLARATION This is to declare that this book represents my own original work, except for the materials gathered from scholarly writings and guidance required from the experts, retired teachers, parents and all other sources, acknowledged appropriately in the book. In connection with the phonetic transcription, I further declare that I have followed the system adopted by “THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY” rather than the I.P.A. in order to avoid certain inconveniences. - The Writer ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I sincerely acknowledge the help and guidance of Dr. K. G. Vijayakrishnan, Head of the Department of Linguistics & Contemporary English, CIEFL, Hyderabad-7, Dr. Dilip Borah, Reader, Department of M.I.L., G.U. and Sri G. S. Pande, Ex- Principal of P. B. College, Gauripur in writing this book. I also acknowledge the help and co-operation of all the lecturers in the Department of English of B. N. college, Dhubri without which it would have not been possible for me to collect the huge amount of data and information required for this book. -

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj

The Serpent Power by Woodroffe Illustrations, Tables, Highlights and Images by Veeraswamy Krishnaraj This PDF file contains the complete book of the Serpent Power as listed below. 1) THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER By WOODROFFE. 2) Ṣaṭ-Cakra-Nirūpaṇa, Six-Cakra Investigation: Description of and Investigation into the Six Bodily Centers by Tantrik Purnananda-Svami (1526 CE). 3) THE FIVEFOLD FOOTSTOOL (PĀDUKĀ-PAÑCAKA THE SIX CENTRES AND THE SERPENT POWER See the diagram in the next page. INTRODUCTION PAGE 1 THE two Sanskrit works here translated---Ṣat-cakra-nirūpaṇa (" Description of the Six Centres, or Cakras") and Pādukāpañcaka (" Fivefold footstool ")-deal with a particular form of Tantrik Yoga named Kuṇḍalinī -Yoga or, as some works call it, Bhūta-śuddhi, These names refer to the Kuṇḍalinī-Śakti, or Supreme Power in the human body by the arousing of which the Yoga is achieved, and to the purification of the Elements of the body (Bhūta-śuddhi) which takes place upon that event. This Yoga is effected by a process technically known as Ṣat-cakra-bheda, or piercing of the Six Centres or Regions (Cakra) or Lotuses (Padma) of the body (which the work describes) by the agency of Kuṇḍalinī- Sakti, which, in order to give it an English name, I have here called the Serpent Power.1 Kuṇḍala means coiled. The power is the Goddess (Devī) Kuṇḍalinī, or that which is coiled; for Her form is that of a coiled and sleeping serpent in the lowest bodily centre, at the base of the spinal column, until by the means described She is aroused in that Yoga which is named after Her. -

Socio-Economic and Demographic Status of Assam: a Comparative Analysis of Assam with India Dr

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies (IJHSSS) A Peer-Reviewed Bi-monthly Bi-lingual Research Journal ISSN: 2349-6959 (Online), ISSN: 2349-6711 (Print) Volume-I, Issue-III, November 2014, Page No. 108-117 Published by Scholar Publications, Karimganj, Assam, India, 788711 Website: http://www.ijhsss.com Socio-Economic and Demographic status of Assam: A comparative analysis of Assam with India Dr. Soma Dhar Research Scholar, Department of Economics, Assam University, Silchar, India Abstract The status of various indicators like, Socio-economic height, representation of demographic, human development ranking etc. can give us a rough picture about our economy. Assam is one of among the eight Sister States of North East India. It is the land of hills, valleys, mighty river Brahmaputra. The paper is based on the secondary data. The broad objective of the paper is to highlight the various facts & figures of Assam and compare these with facts & figures of all India averages. The analysis of the data shows that, though in some cases the performance of state Assam is satisfactorily than the all India average. But in major other areas, the position and performance of Assam is not satisfactorily compared to the all India average. In case of various socio-economic, demographic, human development indicators Assam is far behind from India. Key Wards: Socio-economic condition, Demographic status, Human development rank, Gender development, Nutrition status etc. Socio-economic condition and representation of demographic, human development status etc. are some important indicators which help to measure the development level of any community or state. According to Afzal (1995) and Bose (2006) development of medical science has improved the longevity of human population at the same time there are strong and well documented associations between health and socio-economic and other factors. -

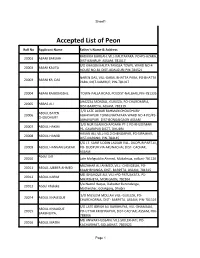

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

Department of Statistics Assam University, Silchar

DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS ASSAM UNIVERSITY, SILCHAR List of Registered Alumni of the Department of Statistics, Assam University, Silchar All of them have pursued M. Sc (Statistics) program from the department Year of Your Current Your Current Mobile completion Affiliation Designation Sl. No. Name E-mail Number Debopama 2016 None None 1 Bhattacharya [email protected] 8133078014 Business, place 2016 Bongaigaon Entrepreneur 2 Dipshikha Baruah [email protected] 8638415125 RKP ASSOCIATES, Janiganj Bazar, 2016 Silchar, Pin-788001 Senior Assistant 3 Piyali Ghosh [email protected] 9435586758 Bakhal Dhar LPS, Anupama Paul [email protected] 7578971845 2016 Cachar Assistant Teacher 4 Srikishan Sarda Smita Dev [email protected] 9954167249 2016 College, Hailakandi Guest faculty 5 1 Year of Your Current Your Current Mobile completion Affiliation Designation Sl. No. Name E-mail Number Alankit House, Guwahati Anupoma Singha [email protected] 6002629655 2016 Ullubari,781007 Data Entry Operator 6 Evelyn learning Pvt. Limited, Ghitorni, New Subject matter expert 2017 Delhi (Statistics) 7 Aditi Chakraborty [email protected] 8486151814 Department of Statistics, Institute of Science, Banaras Senior Research 2017 Hindu University Fellow 8 Utpal Dhar Das [email protected] 9932312411 Bireshwar 2018 None None 9 Bhattacharjee [email protected] 9531045037 2018 None Private Tutor 10 Bornali Das [email protected] 8811932588 Studying PG diploma in Statistical Methods and Analytics at ISI, 2018 Tezpur Student 11 Indrajit Mazumder [email protected] 7002082656 Rangirkhari, Lane 2018 no.1, House no. 16 Student 12 Satabdi Roy [email protected] 9101489340 Studying at teachers' training college , 2018 silchar , assam Students 13 Suraj Goswami [email protected] 8638527300 2019 None None 14 Bikram Jyoti Sinha [email protected] 7086434306 2 Year of Your Current Your Current Mobile completion Affiliation Designation Sl. -

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY of the REGION Ahom

CHAPTER II GEOGRAPHICAL IDENTITY OF THE REGION Ahom and Assam are inter-related terms. The word Ahom means the SHAN or the TAI people who migrated to the Brahma putra valley in the 13th Century A.D. from their original homeland MUNGMAN or PONG situated in upper Bunna on the Irrawaddy river. The word Assam refers to the Brahmaputra valley and the adjoining areas where the Shan people settled down and formed a kingdom with the intention of permanently absorbing in the land and its heritage. From the prehistoric period to about 13th/l4 Century A.D. Assam was referred to as Kamarupa and Pragjyotisha in Indian literary works and historical accounts. Early Period ; Area and Jurisdiction In the Ramayana and Mahabharata and in the Puranik and Tantrik literature, there are numerous references to ancient Assam, which was known as Pragjyotisha in the epics and Kamarupa in the Puranas and Tantras. V^Tien the stories related to it inserted in the Maha bharata, it stretched southward as far as the Bay of Bengal and its western boundary was river Karotoya. This was then a river of the first order and united in its bed the streams which now form the Tista, the Kosi and the Mahanada.^ 14 15 According to the most of the Puranas dealing with geo graphy of the earlier period, the kingdom extended upto the river Karatoya in the west and included Manipur, Jayantia, Cachar, parts of Mymensing, Sylhet, Rangpur and portions of 2 Bhutan and Nepal. The Yogini Yantra (V I:16-18) describes the boundary as - Nepalasya Kancanadrin Bramaputrasye Samagamam Karotoyam Samarabhya Yavad Dipparavasinara Uttarasyam Kanjagirah Karatoyatu pascime tirtharestha Diksunadi Purvasyam giri Kanyake Daksine Brahmaputrasya Laksayan Samgamavadhih Kamarupa iti Khyatah Sarva Sastresu niscitah.