Czech Republic by David Král

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

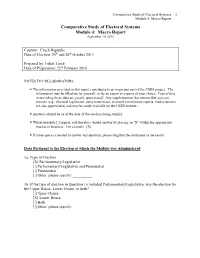

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Czech Republic Date of Election: 25th and 26th October 2013 Prepared by: Lukáš Linek Date of Preparation: 23rd February 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [X] Parliamentary/Legislative [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [X] Lower House [ ] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Party of Citizens Rights-Zemannites (SPO-Z). -

Annual Report 2011 European Values Think-Tank

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 EUROPEAN VALUES THINK-TANK 1 Dear Reader, you are holding the Annual Report of the European Values Think-tank, in which we would like to present our programs realized in 2011. European Values is a non-governmental, pro-European organization that, through education and research activities, works for the development of civil society and a healthy market environment. From 2005, we continue in our role as a unique educational and research organization and think tank, which contributes to public and professional discussion about social, political and economic development in Europe. In the Czech Republic we point out that, due to our membership – active and constructive – of the European Union we can for the first time in modern history participate in decision- making processes concerning the future of Europe, and ensure that we are no longer just a passive object of desire of large powers in our neighbourhood. With our international program, European Values Network, from 2007, we also contribute to a Europe-wide debate on the challenges that Europe faces today. We believe that the public and politicians do not recognize that the benefits of post-war development on our continent can not be taken for granted, and that there are many global trends that threaten the freedom, security and prosperity of Europe as a whole. We analyze these social, political, security and economic trends, and we offer solutions to problems associated with them. In addition to publishing our own books, publications, studies, recommendations, comments, and media contributions and commentary, we also organize seminars, conferences and training courses for professionals and the wider public. -

The Czech President Miloš Zeman's Populist Perception Of

Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics Volume 12 Issue 2 DOI 10.2478/jnmlp-2018-0008 “This is a Controlled Invasion”: The Czech President Miloš Zeman’s Populist Perception of Islam and Immigration as Security Threats Vladimír Naxera and Petr Krčál University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Abstract This paper is a contribution to the academic debate on populism and Islamophobia in contemporary Europe. Its goal is to analyze Czech President Miloš Zeman’s strategy in using the term “security” in his first term of office. Methodologically speaking, the text is established as a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS) of a data set created from all of Zeman’s speeches, interviews, statements, and so on, which were processed using MAXQDA11+. This paper shows that the dominant treatment of the phenomenon of security expressed by the President is primarily linked to the creation of the vision of Islam and immigration as the absolute largest threat to contemporary Europe. Another important finding lies in the fact that Zeman instrumentally utilizes rhetoric such as “not Russia, but Islam”, which stems from Zeman’s relationship to Putin’s authoritarian regime. Zeman’s conceptualization of Islam and migration follows the typical principles of contemporary right-wing populism in Europe. Keywords populism; Miloš Zeman; security; Islam; Islamophobia; immigration; threat “It is said that several million people are prepared to migrate to Europe. Because they are primarily Muslims, whose culture is incompatible with European culture, I do not believe in their ability to assimilate” (Miloš Zeman).1 Introduction The issue of populism is presently one of the crucial political science topics on the levels of both political theory and empirical research. -

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION in CZECH REPUBLIC 25Th and 26Th January 2013 (2Nd Round)

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN CZECH REPUBLIC 25th and 26th January 2013 (2nd round) European Elections monitor Milos Zeman, the new President of the Czech Republic Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy Milos Zeman, former Social Democratic Prime Minister, (1998-2002), honorary chair of the Citizens’ Rights Party (SPO), which he created in 2010, was elected on 26th January President of the Czech Republic with 54.8% of the vote in the country’s first presidential election by direct universal suf- frage. He drew ahead of Foreign Minister Karel Schwarzenberg (Tradition, Responsibility, Prosperity Results 09, TOP09), who won 45.19% of the vote. (2nd round) Milos Zeman rallied the votes of the left and enjoyed Prime Minister called for the support of the Communist strong support on the part of voters in the provinces, Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSCM) between the two whilst Karel Schwarzenberg won Prague and several rounds of the election and received the support of ou- major towns (Brno, Plzen, Liberec, Ceske Budejovice, tgoing President Vaclav Klaus, who explained that he Hradec Kralove, Karlovy Vary and Zlin). The former wanted the head of State to be a citizen who had lived Prime Minister did not receive the support of the official his entire life in the Czech Republic – “in the good and candidate of the biggest left wing party, the Social De- bad times”. Karel Schwarzenberg’s family fled the com- mocratic Party’s (CSSD), Jirí Dienstbier (16.12% of the munist regime that was established in the former Cze- vote in the first round), who refused to give any voting choslovakia in 1948; the Foreign Minister lived in exile advice for the second round, qualifying both candidates for 41 years, notably in Austria, Germany and in Swit- as being “fundamentally on the right” and accused Milos zerland, before returning to his homeland. -

November 2020

EPP Party Barometer November 2020 The Situation of the European People’s Party in the EU (as of: 23 November 2020) Dr Olaf Wientzek (Graphic template: Janine www.kas.de Höhle, HA Kommunikation, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung) Summary & latest developments (I) • In national polls, the EPP family are the strongest political family in 12 countries (including Fidesz); the Socialist political family in 6, the Liberals/Renew in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the Eurosceptic/national conservative ECR in 1. Added together, independent parties lead in Latvia. No polls/elections have taken place in France since the EP elections. • The picture is similar if we look at the strongest single party and not the largest party family: then the EPP is ahead in 12 countries (if you include the suspended Fidesz), the Socialists in 7, the Liberals in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the ECR in one land. • 10 (9 without Orbán) of the 27 Heads of State and Government in the European Council currently belong to the EPP family, 7 to the Liberals/Renew, 6 to the Social Democrats / Socialists, 1 to the Eurosceptic conservatives, and 2 are formally independent. The party of the Slovak head of government belongs to the EPP group but not (yet) to the EPP party; if you include him in the EPP family, there would be 11 (without Orbán 10). • In many countries, the lead is extremely narrow, or, depending on the polls, another party family is ahead (including Italy, Sweden, Latvia, Belgium, Poland). Summary & latest developments (II) • In Romania, the PNL (EPP) has a good starting position for the elections (Dec. -

Factsheet: the Czech Senate

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Czech Senate Wallenstein Palace, seat of the Czech Senate 1. At a glance The Czech Republic is a parliamentary democracy. The Czech Parliament (Parlament České republiky) is made up of two Chambers, both directly elected – the Chamber of Deputies (Poslanecká sněmovna) and the Senate (Senát). The 81 senators in the Senate are elected for six years. Every other year one third of them are elected which makes the Senate a permanent institution that cannot be dissolved and continuously performs its work. Elections to the Senate are held by secret ballot based on universal, equal suffrage, pursuant to the principles of the majority system. Unlike the Lower Chamber, a candidate for the Senate does not need to be on a political party's ticket. Senators, like MPs have the right to take part in election of judges of the Constitutional Court, and may propose new laws. However, the Senate does not get to vote on the country budget and does not supervise the executive directly. The Senate can delay a proposed law, which was approved by the Chamber. However this veto can, with some rare exceptions, be overridden by an absolute majority of the Chamber in a repeated vote. 2. Composition Composition of Senate following the elections of 2-3 October & 9-10 October 2020 Party EP affiliation Seats Občanská demokratická strana (ODS) Civic Democratic Party 27 TOP 09 Starostové a nezávislí (STAN) Mayors and Independents 24 (some MEPs) Křesťanská a demokratická unie - Československá strana lidová (KDU-ČSL) 12 Christian-Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People's Party ANO 2011 Česká strana sociálně demokratická (ČSSD) 9 Czech Social Democratic Party Senátor 21 Senator 21 Česká pirátská strana 7 Czech Pirate Party (some MEPs) Strana zelených Green Party Non-attached 2 TOTAL 81 The next elections must take place in autumn 2022 at the latest. -

LETTER to G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

LETTER TO G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS We write to call for urgent action to address the global education emergency triggered by Covid-19. With over 1 billion children still out of school because of the lockdown, there is now a real and present danger that the public health crisis will create a COVID generation who lose out on schooling and whose opportunities are permanently damaged. While the more fortunate have had access to alternatives, the world’s poorest children have been locked out of learning, denied internet access, and with the loss of free school meals - once a lifeline for 300 million boys and girls – hunger has grown. An immediate concern, as we bring the lockdown to an end, is the fate of an estimated 30 million children who according to UNESCO may never return to school. For these, the world’s least advantaged children, education is often the only escape from poverty - a route that is in danger of closing. Many of these children are adolescent girls for whom being in school is the best defence against forced marriage and the best hope for a life of expanded opportunity. Many more are young children who risk being forced into exploitative and dangerous labour. And because education is linked to progress in virtually every area of human development – from child survival to maternal health, gender equality, job creation and inclusive economic growth – the education emergency will undermine the prospects for achieving all our 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and potentially set back progress on gender equity by years. -

Understanding the Illiberal Turn: Democratic Backsliding in the Czech Republic*

East European Politics ISSN: 2159-9165 (Print) 2159-9173 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjcs21 Understanding the illiberal turn: democratic backsliding in the Czech Republic Seán Hanley & Milada Anna Vachudova To cite this article: Seán Hanley & Milada Anna Vachudova (2018) Understanding the illiberal turn: democratic backsliding in the Czech Republic, East European Politics, 34:3, 276-296, DOI: 10.1080/21599165.2018.1493457 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1493457 Published online: 18 Jul 2018. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fjcs21 EAST EUROPEAN POLITICS 2018, VOL. 34, NO. 3, 276–296 https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1493457 Understanding the illiberal turn: democratic backsliding in the Czech Republic* Seán Hanley a and Milada Anna Vachudovab aSchool of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL, London, UK; bDepartment of Political Science, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Democratic backsliding in Central Europe has so far been most Received 8 December 2017 acute in Hungary and Poland, states once considered frontrunners Accepted 17 June 2018 in democratisation. In this paper, we explore to what extent KEYWORDS developments in another key frontrunner, the Czech Republic, fit Democratization; backsliding; initial patterns of Hungarian/Polish backsliding. Our analysis Czech Republic; populism; centres on the populist anti-corruption ANO movement, led by political parties; Andrej Babis the billionaire Andrej Babiš, which became the largest Czech party in October 2017 after winning parliamentary elections. -

By Anders Hellner Illustration Ragni Svensson

40 essay feature interview reviews 41 NATURAL GAS MAKES RUSSIA STRONGER BY ANDERS HELLNER ILLUSTRATION RAGNI SVENSSON or nearly 45 years, the Baltic was a divided Russia has not been particularly helpful. For the EU, sea. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were which has so many member states with “difficult” incorporated into the Soviet Union. Poland backgrounds in the area, the development of a stra- and East Germany were nominally inde- tegy and program for the Baltic Sea has long held high pendent states, but were essentially governed from priority. This is particularly the case when it comes to Moscow. Finland had throughout its history enjoyed issues of energy and the environment. limited freedom of action, especially when it came to foreign and security policies. This bit of modern his- tory, which ended less than twenty years ago, still in- In June 2009, the EU Commission presented a fluences cooperation and integration within the Baltic proposal for a strategy and action plan for the entire Sea area. region — in accordance with a decision to produce The former Baltic Soviet republics were soon in- such a strategy, which the EU Parliament had reached tegrated into the European Union and the Western in 2006. Immediately thereafter, the European defense alliance NATO. The U.S. and Western Europe Council gave the Commission the task of formulating accomplished this in an almost coup-like manner. It what was, for the EU, a unique proposal. The EU had was a question of acting while Russia was in a weake- never before developed strategies applying to specific ned state. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Biographies of Speakers and Moderators

INTERNATIONAL IDEA Supporting democracy worldwide Biographies of Speakers and Moderators 20 November 2019 Rue Belliard 101, 1040 Brussels www.idea.int @Int_IDEA InternationalIDEA November 20, 2019 The State of Democracy in East-Central Europe Opening Session Dr. Kevin Casas-Zamora, Secretary-General, International IDEA Dr. Casas-Zamora is the Secretary-General of International IDEA and Senior Fellow at the Inter-American Dialogue. He was member of Costa Rica’s Presidential Commission for State Reform and managing director at Analitica Consultores. Previously, he was Costa Rica’s Second Vice President and Minister of National Planning; Secretary for Political A airs at the Organization of American States; Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution; and National Coordinator of the United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Report. Dr. Casas-Zamora has taught in multiple higher education institutions. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the University of Oxford. His doctoral thesis, on Political Fi- nance and State Subsidies for Parties in Costa Rica and Uruguay, won the 2004 Jean Blondel PhD Prize of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR). Mr. Karl-Heinz Lambertz, President of the European Committee of the Regions Mr. Karl-Heinz Lambertz was elected as President of the European Committee of the Regions (CoR) in July 2017 a er serving as First Vice-President. He is also President of the Parliament of the German-speaking Community of Belgium. His interest in politics came early in his career having served as President of the German-speaking Youth Council. He then became Member of Parliament of the Ger- man-speaking Community in 1981. -

Policy Learning, Fast and Slow: Market-Oriented Reforms of Czech and Polish Healthcare Policy, 1989-2009

Policy Learning, Fast and Slow: Market-Oriented Reforms of Czech and Polish Healthcare Policy, 1989-2009 Tamara Popić Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Florence, 24 November 2014 (defence) European University Institute Department of Political and Social Sciences Policy Learning, Fast and Slow: Market-Oriented Reforms of Czech and Polish Healthcare Policy, 1989-2009 Tamara Popić Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of Political and Social Sciences of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof Sven Steinmo, EUI (Supervisor) Prof László Bruszt, EUI Prof Ana Marta Guillén Rodríguez, University of Oviedo Prof Ellen Immergut, Humboldt University Berlin © Popić, 2014 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Abstract What determines the pace of policy innovation and change? Why, in other words, do policy makers in some countries innovate faster than in others? This thesis challenges conventional explanations, according to which policy change occurs in response to class conflict, partisan preferences, power of professional groups, or institutional and policy legacies. The thesis instead argues that different paths of policy change can be best explained by the different learning processes by which policy makers develop ideas for new policies in reaction to old policies. The thesis draws upon both ideational and institutional streams of literature on policy change, and develops its argument that policy change, understood as a learning process, is a result of interactions between three different, yet interdependent factors – ideas, interests and institutions.