The Practice of Dapa Making: a Case Studyfrom Trashiyangtse in Bhutan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View English PDF Version

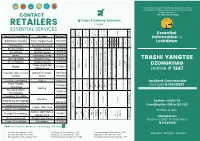

on ” 1247 17608432 17343588 Please stay alert. Chairperson His Majesty The King Hotline # 4141 Essential Lockdown Eastern COVID-19 Information Stay Home - Stay Safe - Save Lives DZONGKHAG Hotline # Dzongda Incident Commander Eastern COVID-19 Task Force Coordination Office (ECCO) It will undo everything that we have achieved so far. “ A careless person’s mistake will undo all our efforts. TRASHI YANGTSE Name Contact # Zone (Yangtse) Delivery time Delivery Day Order Day Rigney (Rigney including Hospital, RNR, NSC, BOD, 17641121 NRDCL ) 8:00 AM to 12:00 17834589/77218 PM 454 Baechen SATURDAY Retailers 17509633 SUNDAY ( 7:00 AM to 17691083 Main Town (below Dzong and Choeten Kora 12:00 PM to 3:00 6:00 PM) 17818250 area) PM 17282463 Baylling (above Dzong, including Rinchengang till 3:00 PM to 6:00 17699183 BCS) PM 6:00 AM to 17696122 Baylling, Baechen, Rigney and Main Town THURSDAY Vendors 5:00PM ( SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 Agriculture 6:00 AM to 17302242 From Serkhang Chu till Choeten Kora PM) 5:00PM 6:00 AM to MONDAY 17874349 Rigney & Baechen Zone (Yangtse and Doksum) THURSDAY Yangtse Vendors 5:00PM WEDNESDAY & SATURDAY ( Jomotshangkha Drungkhag -1210 Nganglam Drungkhag - 1195 Samdrupcholing Drungkhkag - 1191 Livestock 6:00 AM to 6:00 AM to 6:00 17532906 Main Town & Baylling Zone PM) 5:00PM TUESDAY & 77885806/77301 2:00 PM to 5:00 LPG Delivery Yangtse Throm TUESDAY & FRIDAY FRIDAY ( 9:00 AM 070 PM to 1:00 PM) Order & Delivery Schedule 17500690 FRIDAY ( Meat Shop Yangtse Throm 7:00 AM to 1:00PM SATURDAY 6:00 AM to 6:00 77624407 PM) Pharmacy 17988376 Doksum & Yangtse Throm As & when As & When / # 3 9 1 3 3 1 3 9 8 9 0 1 6 7 2 8 5 3 6 9 3 8 3 6 8 5 8 2 4 8 5 2 7 t 5 0 7 5 6 0 4 6 5 4 4 1 5 0 8 5 1 2 1 5 c 7 8 9 2 5 9 3 9 4 9 4 6 2 1 7 7 8 8 1 3 a 5 5 0 7 4 2 4 t 0 3 9 5 7 8 9 9 0 6 1 4 8 7 8 5 6 5 3 7 n 5 8 6 6 3 2 6 5 5 8 8 6 8 8 4 4 8 9 5 8 o 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 6 7 7 7 7 7 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 C 1 . -

Geographical and Historical Background of Education in Bhutan

Chapter 2 Geographical and Historical Background of Education in Bhutan Geographical Background There is a great debate regarding from where the name of „Bhutan‟ appears. In old Tibetan chronicles Bhutan was called Mon-Yul (Land of the Mon). Another theory explaining the origin of the name „Bhutan‟ is derived from Sanskrit „Bhotanta‟ where Tibet was referred to as „Bhota‟ and „anta‟ means end i. e. the geographical area at the end of Tibet.1 Another possible explanation again derived from Sanskrit could be Bhu-uttan standing for highland, which of course it is.2 Some scholars think that the name „Bhutan‟ has come from Bhota (Bod) which means Tibet and „tan‟, a corruption of stan as found in Indo-Persian names such as „Hindustan‟, „Baluchistan‟ and „Afganistan‟etc.3 Another explanation is that “It seems quite likely that the name „Bhutan‟ has come from the word „Bhotanam‟(Desah iti Sesah) i.e., the land of the Bhotas much the same way as the name „Iran‟ came from „Aryanam‟(Desah), Rajputana came from „Rajputanam‟, and „Gandoana‟ came from „Gandakanam‟. Thus literally „Bhutan‟ means the land of the „Bhotas‟-people speaking a Tibetan dialect.”4 But according to Bhutanese scholars like Lopen Nado and Lopen Pemala, Bhutan is called Lho Mon or land of the south i.e. south of Tibet.5 However, the Bhutanese themselves prefer to use the term Drukyul- the land of Thunder Dragon, a name originating from the word Druk meaning „thunder dragon‟, which in turn is derived from Drukpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. Bhutan presents a striking example of how the geographical setting of a country influences social, economic and political life of the people. -

Bhutan's Accelerating Urbanization

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No.: 62072 Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT REPORT KINGDOM OF BHUTAN URBAN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (CREDIT 3310) June 13, 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized IEG Public Sector Evaluation Independent Evaluation Group Public Disclosure Authorized Currency Equivalents (annual averages) Currency Unit = Bhutanese Ngultrum (Nu) 1999 US$1.00 Nu 43.06 2000 US$1.00 Nu 44.94 2001 US$1.00 Nu 47.19 2002 US$1.00 Nu 48.61 2003 US$1.00 Nu 46.58 2004 US$1.00 Nu 45.32 2005 US$1.00 Nu 44.10 2006 US$1.00 Nu 45.31 2007 US$1.00 Nu 41.35 2006 US$1.00 Nu 43.51 2007 US$1.00 Nu 48.41 Abbreviations and Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank BNUS Bhutan National Urbanization Strategy CAS Country Assistance Strategy CPS Country Partnership Strategy DANIDA Danish International Development Agency DUDES Department of Urban Development and Engineering Services (of MOWHS) GLOF Glacial Lake Outburst Flood ICR Implementation Completion Report IEG Independent Evaluation Group IEGWB Independent Evaluation Group (World Bank) MOF Ministry of Finance MOWHS Ministry of Works & Human Settlement PPAR Project Performance Assessment Report RGOB Royal Government of Bhutan TA Technical Assistance Fiscal Year Government: July 1 – June 30 Director-General, Independent Evaluation : Mr. Vinod Thomas Director, IEG Public Sector Evaluation : Ms. Monika Huppi (Acting) Manager, IEG Public Sector Evaluation : Ms. Monika Huppi Task Manager : Mr. Roy Gilbert i Contents Principal Ratings ............................................................................................................... -

Small Area Estimation of Poverty in Rural Bhutan

Small Area Estimation of Poverty in Rural Bhutan Technical Report jointly prepared by National Statistics Bureau of Bhutan and the World Bank June 21, 2010 National Statistics Bureau South Asia Region Economic Policy and Poverty Royal Government of Bhutan The World Bank Acknowledgements The small area estimation of poverty in rural Bhutan was carried out jointly by National Statistics Bureau (NSB) of Bhutan and a World Bank team – Nobuo Yoshida, Aphichoke Kotikula (co-TTLs) and Faizuddin Ahmed (ETC, SASEP). This report summarizes findings of detailed technical analysis conducted to ensure the quality of the final poverty maps. Faizuddin Ahmed contributed greatly to the poverty estimation, and Uwe Deichman (Sr. Environmental Specialist, DECEE) provided useful inputs on GIS analysis and creation of market accessibility indicators. The team also acknowledges Nimanthi Attapattu (Program Assistant, SASEP) for formatting and editing this document. This report benefits greatly from guidance and inputs from Kuenga Tshering (Director of NSB), Phub Sangay (Offtg. Head of Survey/Data Processing Division), and Dawa Tshering (Project Coordinator). Also, Nima Deki Sherpa (ICT Technical Associate) and Tshering Choden (Asst. ICT Officer) contributed to this analysis, particularly at the stage of data preparation, and Cheku Dorji (Sr. Statistical Officer) helped to prepare the executive summary and edited this document. The team would like to acknowledge valuable comments and suggestions from Pasang Dorji (Sr. Planning Officer) of the Gross National Happiness Commission (GNHC) and from participants in the poverty mapping workshops held in September and December 2009 in Thimphu. This report also benefits from the feasibility study conducted on Small Area Estimation of poverty by the World Food Program in Bhutan. -

Black-Necked Crane Conservation Action Plan for Bhutan (2021 - 2025)

BLACK-NECKED CRANE CONSERVATION ACTION PLAN FOR BHUTAN (2021 - 2025) Department of Forests and Park Services Ministry of Agriculture and Forests Royal Government of Bhutan in collaboration with Royal Society for Protection of Nature Plan prepared by: 1. Jigme Tshering, Royal Society for Protection of Nature 2. Letro, Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services 3. Tandin, Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services 4. Sonam Wangdi, Nature Conservation Division, Department of Forests and Park Services Plan reviewed by: 1. Dr. Sherub, Specialist, Ugyen Wangchuck Institute for Conservation and Environmental Research, Department of Forests and Park Services. 2. Rinchen Wangmo, Director, Program Development Department, Royal Society for Protection of Nature. Suggested citation: BNC 2021. Black-necked Crane Conservation Action Plan (2021-2025), Department of Forests and Park Services, Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, and Royal Society for Protection of Nature, Thimphu, Bhutan དཔལ་辡ན་འབྲུག་ག筴ང་། སོ་ནམ་དང་ནགས་ཚལ་辷ན་ཁག། ནགས་ཚལ་དང་ག콲ང་ཀ་ཞབས་ཏོག་ལས་ݴངས། Royal Government of Bhutan Ministry of Agriculture and Forests Department of Forests and Park Services DIRECTOR Thimphu MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR The Department of Forests and Park Services has been mandated to manage and conserve Bhutan's rich biodiversity. As such the department places great importance in the conservation of the natural resources and the threatened wild fauna and flora. With our consistent conservation efforts, we have propelled into the 21st century as a champion and a leader in environmental conservation in the world. The conservation action plans important to guide our approaches towards conserving the species that are facing considerable threat. -

![AFS 2016-17 [Eng]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8579/afs-2016-17-eng-528579.webp)

AFS 2016-17 [Eng]

ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENTS of the ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN for the YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2017 Department of Public Accounts Ministry of Finance ii Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................... 1 2. BASIS FOR PREPARATION .............................................................................. 1 3. FISCAL PERFORMANCE .................................................................................. 1 4. RECEIPTS AND PAYMENTS ............................................................................ 3 5. GOVERNMENT RECEIPTS BY SOURCES .................................................... 4 5.1 DOMESTIC REVENUE ............................................................................... 5 5.2 EXTERNAL GRANTS ................................................................................. 6 5.3 BORROWINGS EXTERNAL BORROWINGS .......................................... 8 5.4 RECOVERY OF LOANS ........................................................................... 10 5.5 OTHER RECEIPTS AND PAYMENTS .................................................... 11 6. OPERATIONAL RESULTS .............................................................................. 12 6.1 GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE............................................................. 12 7. BUDGET UTILISATION .................................................................................. 25 7.1 UTILIZATION OF CAPITAL BUDGET................................................... 25 8. ACHIEVEMENT OF FISCAL -

Zhemgang Dzongkhag

༼ར꽼ང་ཁག་རྐྱེན་ངན་འ潲ན་སྐྱོང་དང་འབྱུང་፺ས་པ荲་ཐབས་ལམ་འཆར་ག筲།༽ Dzongkhag Disaster Management and Contingency Plan Dzongkhag Administration, Zhemgang ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF BHUTAN 2020 DISASTER MANAGEMENT & CONTINGENCY PLAN OF ZHEMGANG DZONGKHAG [2] Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY _________________________________________________________ Error! Bookmark not defined. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ________________________________________________________________________________ 4 ACRONYMS __________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 SCOPE: ______________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 OBJECTIVES: ________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 CHAPTER 1: OVERVIEW OF THE DZONGKHAG ___________________________________________________________ 7 BACKGROUND _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PROFILE________________________________________________________________________ 8 FIGURE 1 – ORGANOGRAM OF DZONGKHAG ADMINISTRATION __________________________________________________ 12 1.3: WEATHER AND CLIMATE _________________________________________________________________________________ 14 1.4: DEMOGRAPHY ___________________________________________________________________________________________ 14 1.5 ECONOMY _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 14 CHAPTER 2: DZONGKHAG DISASTER MANAGEMENT -

Ngoedrup-Tse

The Ngoedrup-Tse Volume II Issue I Bi-Annual Newsletter January-June 2019 A Note from Dzongdag His Majesty the Druk Gyalpo Birth Anni- Within the last two years of my association with the versary Celebration Chhukha Dzongkhag as the Dzongdag, I have had several opportunities to traverse through different Gewogs, interact with diverse group of people, and listen to their personal stories and aspirations they have for themselves and the nation. These are precious moments that, I feel comes only once in our career, and that too if we happen to serve in Dzongkhags and Gewogs! Many of my colleagues echo similar feelings on their return from field visits. On my part, I had a great privilege to sensitize people on their rights and responsibilities as a citizen of this great nation with particular emphasis on their constitutional Chhukha Dzongkhag Administration celebrated the 39th Birth obligation to uphold and strengthen peace and security Anniversary of our beloved Druk Gyalpo at Chhukha Central of the country and our unique Bhutanese values School. The day started with lighting of thousand butter lamps and besides other policies, plans and programs of different offering of prayers at Kuenray of Ngoedrup-Tse Dzong at 7.30 am governmental agencies. led by Venerable Lam Neten, Dasho Dzongdag, Dasho Drangpon, Dzongrab, regional and sector heads for His Majesty’s good health Every day is a new beginning with opportunities and and long life. challenges that calls for learning, unlearning and relearning with ensuing diagnostic assessment and The Chief Guest for the memorable day was Dasho Dzongdag. -

Development and Its Impacts on Traditional Dispute Resolution in Bhutan

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 63 New Directions in Domestic and International Dispute Resolution 2020 Formalizing the Informal: Development and its Impacts on Traditional Dispute Resolution in Bhutan Stephan Sonnenberg Seoul National University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Dispute Resolution and Arbitration Commons Recommended Citation Stephan Sonnenberg, Formalizing the Informal: Development and its Impacts on Traditional Dispute Resolution in Bhutan, 63 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 143 (2020), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol63/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FORMALIZING THE INFORMAL: DEVELOPMENT AND ITS IMPACTS ON TRADITIONAL DISPUTE RESOLUTION IN BHUTAN Stephan Sonnenberg* INTRODUCTION Bhutan is a small landlocked country with less than a million inhabitants, wedged between the two most populous nations on earth, India and China.1 It is known for its stunning Himalayan mountain ranges and its national development philosophy of pursuing “Gross National Happiness” (GNH).2 This paper argues, however, that Bhutan should also be known for its rich heritage of traditional dispute resolution. That system kept the peace in Bhutanese villages for centuries: the product of Bhutan’s unique history and its deep (primarily Buddhist) spiritual heritage. Sadly, these traditions are today at risk of extinction, victims—it is argued below—of Bhutan’s extraordinary process of modernization. -

Buddhism: It,S Role and Importance in Bhutanese Culture

Mukt Shabd Journal ISSN NO : 2347-3150 Buddhism: it,s role and importance in Bhutanese culture Research Scholar Pankaj Kumar Department of Western History University of Lucknow Abstract Bhutan is situated along the southern slopes of the Great Himalaya range. It is bounded by the table-land of Tibet on the north ; the plains of jalpaiguri district of west Bengal and Goalpara , kamrup and Darrang districts of Assam in the south; the Chumbi valley ( Tibet) , Sikkim and Darjeeling district of west Bengal in the west ; and the kameng district of the Arunachal Pradesh on the east. Before the introduction of Buddhism in Bhutan, the prevalent religion was Bon. Some scholars assert that it was imported from Tibet and India, perhaps in the eighth century when Padmasambhava introduced his lineages of Vajrayana Buddhism into Tibet and the Himalayas. The history of Bhutan is mainly the history of spreading of Buddhism and it,s different sects those creates main bases for Bhutanese culture from ancient time to till now. Many famous monks such like Guru Padmasambhawa presented many religious rituals and symbols before Bhutanese people those became traditions and culture. Buddhism and Bhutanese culture are seems like mirror of each other. Bhutanese dresses, dances, festivals, rituals, paintings etc. directly follows Buddhism. Key word:- Bhutan, Buddhism, Culture, Padmasambhawa, Ngawang Namgyal, Driglamnamzha, Introduction Bhutan is situated along the southern slopes of the Great Himalaya range. It is bounded by the table-land of Tibet on the north ; the plains of jalpaiguri district of west Bengal and Goalpara , kamrup and Darrang districts of Assam in the south; the Chumbi valley ( Tibet) , Sikkim and Darjeeling district of west Bengal in the west ; and the kameng district of the Arunachal Pradesh on the east.1 Bhutan is situated 88 deg.45 min to 92 deg. -

Buddhist Art and Architecture Ebook

BUDDHIST ART AND ARCHITECTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert E Fisher | 216 pages | 24 May 1993 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500202654 | English | London, United Kingdom GS Art and Culture | Buddhist Architecture | UPSC Prep | NeoStencil Mahabodhi Temple is an example of one of the oldest brick structures in eastern India. It is considered to be the finest example of Indian brickwork and was highly influential in the development of later architectural traditions. Bodhgaya is a pilgrimage site since Siddhartha achieved enlightenment here and became Gautama Buddha. While the bodhi tree is of immense importance, the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodhgaya is an important reminder of the brickwork of that time. The Mahabodhi Temple is surrounded by stone ralling on all four sides. The design of the temple is unusual. It is, strictly speaking, neither Dravida nor Nagara. It is narrow like a Nagara temple, but it rises without curving, like a Dravida one. The monastic university of Nalanda is a mahavihara as it is a complex of several monasteries of various sizes. Till date, only a small portion of this ancient learning centre has been excavated as most of it lies buried under contemporary civilisation, making further excavations almost impossible. Most of the information about Nalanda is based on the records of Xuan Zang which states that the foundation of a monastery was laid by Kumargupta I in the fifth century CE. Vedika - Vedika is a stone- walled fence that surrounds a Buddhist stupa and symbolically separates the inner sacral from the surrounding secular sphere. Talk to us for. UPSC preparation support! Talk to us for UPSC preparation support! Please wait Free Prep. -

Festivals and Mountaintop Temples of Bhutan

BHUTAN Festivals and Mountaintop Temples of Bhutan DATES Sep 28–Oct 06, 2017 COST 3,999.00 USD ITINER ARY 9 days, 8 nights BOOK YOUR TRIP Be one of the lucky few to experience this tiny, landlocked nation during its lively festival season. Celebrate the Land of the Thunder Dragon alongside locals through traditional Bhutanese dance, song, and cuisine. Perhaps best-known for its chart-topping measure of Gross National Happiness, this Himalayan nation is home to dramatic landscapes, mystical temples, and fewer than one million people. On this unique trip, you’ll see firsthand how Bhutan is one of the greenest and most sustainable countries on the planet. This adventure is designed for travelers of all ages and most levels of physical ability and is limited to 25 explorers. (See “Note on Hiking and Health” in the Fine Print.) HIGHLIGHTS National Festivals: Experience the sights and sounds of two teschus (festivals)—the first, in Thimphu, is the largest of Bhutan's Buddhist festivals. The second, in Gangtey in the Phobjikha Valley, is less frequented by tourists. At each, you’ll see traditional religious and tantric dance performances and celebrate, pray, and receive blessings for the year ahead. Wildlife and Conservation: The Bhutanese constitution mandates that 60 percent of the country remains forested. During this beautiful time of year, we’ll hike through Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Park, explore the Royal Botanical Park, and spot birds, wild goats, and grey langurs. the Royal Botanical Park, and spot birds, wild goats, and grey langurs. Spiritual Practice: Raise peace flags on the Dochula Pass, meet with Buddhist spiritual leaders, and take in the evening chants at historic temples.