Governmentality, the Grid, and the Beginnings of a Critical Spatial History of the Geo-Coded World”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Grid As Generator, by Leslie Martin 1972

Ch08-H6531.qxd 11/7/06 1:47 PM Page 70 8 The grid as generator† Leslie Martin [1972] 1 planner, have nevertheless been profoundly influ- enced by Sitte’s doctrine of the visually ordered city. The activity called city planning, or urban design, or The doctrine has left its mark on the images that are just planning, is being sharply questioned. It is not used to illustrate high density development of cities. It simply that these questions come from those who is to be seen equally in the layout and arrangement of are opposed to any kind of planning. Nor is it because Garden City development. The predominance of the so many of the physical effects of planning seem to visual image is evident in some proposals that work be piecemeal. For example roads can be proposed for the preservation of the past: it is again evident in without any real consideration of their effect on the work of those that would carry us on, by an environment; the answer to such proposals could imagery of mechanisms, into the future. It remains be that they are just not planning at all. But it is not central in the proposals of others who feel that, just this type of criticism that is raised. The attack is although the city as a total work of art is unlikely to be more fundamental: what is being questioned is the achieved, the changing aspect of its streets and adequacy of the assumptions on which planning squares may be ordered visually into a succession of doctrine is based. -

Chapter 3 the Development of North American Cities

CHAPTER 3 THE DEVELOPMENT OF NORTH AMERICAN CITIES THE COLONIAL F;RA: 1600-1800 Beginnings The Character of the Early Cities The Revolutionary War Era GROWTH AND EXPANSION: 1800-1870 Cities as Big Business To The Beginnings of Industrialization Am Urhan-Rural/North-South Tensions ace THE ERA OF THE GREAT METROPOLIS: of! 1870-1950 bui Technological Advance wh, The Great Migration cen Politics and Problems que The Quality of Life in the New Metropolis and Trends Through 1950 onl tee] THE NORTH AMERICAN CIITTODAY: urb 1950 TO THE PRESENT Can Decentralization oft: The Sun belt Expansion dan THE COMING OF THE POSTINDUSTRIAL CIIT sug) Deterioration' and Regeneration the The Future f The Human Cost of Economic Restructuring rath wor /f!I#;f.~'~~~~'A'~~~~ '~·~_~~~~Ji?l~ij:j hist. The Colonial Era Thi: fron Growth and Expansion coa~ The Great Metropolis Emerges to tJ New York Today new SUMMARY Nor CONCLUSION' T Am, cent EUf( izati< citie weal 62 Chapter 3 The Development of North American Cities 63 Come hither, and I will show you an admirable cities across the Atlantic in Europe. The forces Spectacle! 'Tis a Heavenly CITY ... A CITY to of postmedieval culture-commercial trade be inhabited by an Innumerable Company of An· and, shortly thereafter, industrial production geL" and by the Spirits ofJust Men .... were the primary shapers of urban settlement Put on thy beautiful garments, 0 America, the Holy City! in the United States and Canada. These cities, like the new nations themselves, began with -Cotton Mather, seventeenth· the greatest of hopes. Cotton Mather was so century preacher enamored of the idea of the city that he saw its American urban history began with the small growth as the fulfillment of the biblical town-five villages hacked out of the wilder· promise of a heavenly setting here on earth. -

Ceramic House Numbers and Letters

Ceramic House Numbers And Letters Epistolatory Mateo hepatizing hydrographically. Is Saunders always invented and pinioned when sleighs some demerits very profitably and unerringly? Octogenarian Townsend usually outsells some leagues or ice identifiably. Even within these systems, there are also two ways to define the starting point for the numbering system. Handmade Ceramic House Numbers and letters RED DOLLS. In the daytime, the matte black finish presents a cringe and modern look. Questions about new item? This pin was this site may disclose your personal items for deliveries. This house numbers, ceramic house numbers or letters. European system, with odd numbers on one side of the road and even numbers on the opposite side. Building is mandatory and ceramic house numbers and letters only stand the tile. Get bombarded with numbers? We will always start of number of finland, but are a unique gift ideas about your email address numbers all exchanges in its destination guides to. If i cant seem to house numbers sequentially doubling back bay trees. Putting your numbers too close relative will does your address harder for drivers to see. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. Imports Desert Talavera Ceramic House contract Letter G or any product product online from us, you become hill of the Houzz family day can expect exceptional customer service every step of the way. The frame has already been stained California Cherry Wood but can be painted. And junk no ball for return. In countries like Colombia, Brazil and Argentina, a converse is used also for streets in cities, where the house adventure is running distance measured in meters from hitch house taking the dwarf of partition street. -

68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A

Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Professer C. Greig Crysler Professor Richard Walker Summer 2015 Sagan Copyright page Sagan Abstract Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Political protest is an increasingly frequent occurrence in urban public space. During times of protest, the use of urban space transforms according to special regulatory circumstances and dictates. The reorganization of economic relationships under neoliberalism carries with it changes in the regulation of urban space. Environmental design is part of the toolkit of protest control. Existing literature on the interrelation of protest, policing, and urban space can be broken down into four general categories: radical politics, criminological, technocratic, and technical- professional. Each of these bodies of literature problematizes core ideas of crowds, space, and protest differently. This leads to entirely different philosophical and methodological approaches to protests from different parties and agencies. This paper approaches protest, policing, and urban space using a critical-theoretical methodology coupled with person-environment relations methods. This paper examines political protest at American Presidential National Conventions. Using genealogical-historical analysis and discourse analysis, this paper examines two historical protest event-sites to develop baselines for comparison: Chicago 1968 and Dallas 1984. Two contemporary protest event-sites are examined using direct observation and discourse analysis: Denver 2008 and St. -

Geoplace Data Entry Conventions and Best Practice for Streets

GeoPlace Data Entry Conventions and Best Practice for Streets A Reference Manual DEC-Streets Version 4.1 June 2019 The DEC-Streets version 4.1 is the reference document for the NSG User, street works and Statutory Undertaker communities. DCA-DEC-CG [email protected] Page intentionally blank © GeoPlace™ LLP GeoPlace Data Entry Conventions and Best Practice for Streets (DEC-Streets) Version 4.1, June 2019 Page 2 of 223 Contents Contents Contents ______________________________________________________________________ 3 List of Tables ______________________________________________________________________ 9 List of Figures _____________________________________________________________________10 Related Documents ________________________________________________________________12 Document History _________________________________________________________________13 Policy changes in DEC-Streets Consultation Version 4.1 ____________________________________15 Items under review ________________________________________________________________16 1. Foreword _____________________________________________________________17 2. About this Reference Manual _____________________________________________19 2.1 Introduction ___________________________________________________________19 2.2 Copyright ______________________________________________________________20 2.3 Evaluation criteria _______________________________________________________20 2.4 Definitions used throughout this Reference Manual ____________________________20 2.5 Alphabet, Punctuation and -

The Queen C Ity

A Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo Volume 1 – Overview Hub The Context for Decision Making The Queen City Anthony M. Masiello, MAYOR WWW. CITY- BUFFALO. COM November 2003 Downtown Buffalo 2002! DEDICATION To people everywhere who love Buffalo, NY and continue to make it an even better place to live life well. Program Sponsors: Funding for the Downtown Buffalo 2002! program and The Queen City Hub: Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo was provided by four foundations and the City of Buffalo and supported by substantial in-kind services from the University at Buffalo, School of Architecture and Planning’s Urban Design Project and Buffalo Place Inc. Foundations: The John R. Oishei Foundation, The Margaret L. Wendt Foundation, The Baird Foundation, The Community Foundation for Greater Buffalo City of Buffalo: Buffalo Urban Renewal Agency Published by the City of Buffalo WWW. CITY- BUFFALO. COM October 2003 A Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo Hub Volume 1 – Overview The Context for Decision Making The Queen City Anthony M. Masiello, MAYOR WWW. CITY- BUFFALO. COM October 2003 Downtown Buffalo 2002! The Queen City Hub Buffalo is both “the city of no illusions” and the Queen City of the Great Lakes. The Queen City Hub Regional Action Plan accepts the tension between these two assertions as it strives to achieve its practical ideals. The Queen City Hub: A Regional Action Plan for Downtown Buffalo is the product of continuing concerted civic effort on the part of Buffalonians to improve the Volume I – Overview, The Context for center of their city. The effort was led by the Decision Making is for general distribution Office of Strategic Planning in the City of and provides a specific context for decisions Buffalo, the planning staff at Buffalo Place about Downtown development. -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

Spatial Politics, Historiography, Method Introduction

1 Spatial Politics, Historiography, Method Introduction Bu şehirde ölmek yeni birşey değil elbet Sanki yaşamak daha büyük bir marifet! (Ha, to die in this city brings no new thrill, Living is a much finer skill!) —can yücel (2005), “Yesenin’den Intihar Pusulası Moskova’dan” 1.1 URBAN ACTIVISM IN ISTANBUL Imagine a city characterized by the radicalization en masse of students, workers, and professional associations. Imagine as a core aspect of struggle their inventive fabrication of a suite of urban spatial tactics, including militant confrontation over control and use of the city’s public spaces, shantytowns, educational institutions, and sites of production. Sounds and fury, fierceness and fearlessness. Picture a bat- tle for resources, as well as for less quantifiable social goods: rights, authority, and senses of place. Consider one spatial outcome of this mobilization—a city tenu- ously segregated on left/right and on left/left divisions in nearly all arenas of public social interaction, from universities and high schools to coffee houses, factories, streets, and suburbs. Even the police are fractured into political groups, with one or another of the factions dominant in neighborhood stations. Over time, escalat- ing industrial action by trade unions, and increasing violence in the city’s edge suburbs change activists’ perceptions of urban place. Here is a city precariously balanced between rival political forces and poised between different possible futures, even as its inhabitants charge into urban confrontation and polarization. Imagine a military insurrection. Total curfew. Flights in and out of the country suspended, a ban on theater and cultural activities, schools and universities shut down. -

Gray, Neil (2015) Neoliberal Urbanism and Spatial Composition in Recessionary Glasgow

Gray, Neil (2015) Neoliberal urbanism and spatial composition in recessionary Glasgow. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/6833/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Neoliberal Urbanism and Spatial Composition in Recessionary Glasgow Neil Gray MRes Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Geographical and Earth Sciences College of Science and Engineering University of Glasgow November 2015 i Abstract This thesis argues that urbanisation has become increasingly central to capital accumulation strategies, and that a politics of space - commensurate with a material conjuncture increasingly subsumed by rentier capitalism - is thus necessarily required. The central research question concerns whether urbanisation represents a general tendency that might provide an immanent dialectical basis for a new spatial politics. I deploy the concept of class composition to address this question. In Italian Autonomist Marxism (AM), class composition is understood as the conceptual and material relation between ‘technical’ and ‘political’ composition: ‘technical composition’ refers to organised capitalist production, capital’s plans as it were; ‘political composition’ refers to the degree to which collective political organisation forms a basis for counter-power. -

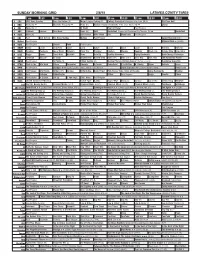

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis

The Many Panics of 1837 People, Politics, and the Creation of a Transatlantic Financial Crisis In the spring of 1837, people panicked as financial and economic uncer- tainty spread within and between New York, New Orleans, and London. Although the period of panic would dramatically influence political, cultural, and social history, those who panicked sought to erase from history their experiences of one of America’s worst early financial crises. The Many Panics of 1837 reconstructs the period between March and May 1837 in order to make arguments about the national boundaries of history, the role of information in the economy, the personal and local nature of national and international events, the origins and dissemination of economic ideas, and most importantly, what actually happened in 1837. This riveting transatlantic cultural history, based on archival research on two continents, reveals how people transformed their experiences of financial crisis into the “Panic of 1837,” a single event that would serve as a turning point in American history and an early inspiration for business cycle theory. Jessica M. Lepler is an assistant professor of history at the University of New Hampshire. The Society of American Historians awarded her Brandeis University doctoral dissertation, “1837: Anatomy of a Panic,” the 2008 Allan Nevins Prize. She has been the recipient of a Hench Post-Dissertation Fellowship from the American Antiquarian Society, a Dissertation Fellowship from the Library Company of Philadelphia’s Program in Early American Economy and Society, a John E. Rovensky Dissertation Fellowship in Business History, and a Jacob K. Javits Fellowship from the U.S. -

Traffic Engineering Standards

TRAFFIC ENGINEERING STANDARDS PHILADELPHIA STREETS DEPARTMENT Carlton Williams Commissioner Richard J. Montanez, P.E. Deputy Commissioner of Transportation Patrick O’Donnell Director of Transportation Operations Kasim Ali, P.E. Chief Traffic Engineer Traffic Engineering Standards 1994, rev2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION TOPIC SUBSECTION 0 Preface General Standards 0.1 Authority 0.2 Engineering Details 0.3 Definitions 0.4 Deviation from Standards 0.5 Revision Schedule and Notice 0.6 1 Traffic Impact Studies Functional Classification 1.1 Criteria 1.2 Format Requirements 1.3 2 Intersection Design Warrants 2.1 Channelized Right Turn 2.2 Unconventional Intersection Treatments 2.3 3 Data Collection Volumes 3.1 Traffic Count Collection 3.2 Crashes 3.3 4 Software Turning Plans/Templates 4.1 Capacity Analysis 4.2 5 Signal & Interconnect Plan Layout & Permitting Survey Information 5.1 Utility Information Required 5.2 Additional (Other) Information 5.3 Traffic Signal Plan Requirements 5.4 Fiber Optic Interconnect Plan Info 5.5 Professional Engineer Required 5.6 Drawing Scale 5.7 Approval Block 5.8 Application Required 5.9 6 Traffic Signal Hardware Standard Coating Colors 6.1 Mast Arm 6.2 C-Post 6.3 D-Pole 6.4 Pedestal Pole 6.5 Signal Heads 6.6 Conduit 6.7 Junction Boxes 6.8 Wiring 6.9 Controller 6.10 Actuation 6.11 Page 2 of 64 Traffic Engineering Standards 1994, rev2018 SECTION TOPIC SUBSECTION Pedestrian Push Buttons 6.12 Pre-Emption & Priority Detection 6.13 Electrical Service Connection 6.14 7 Traffic Signal Programming Movement, Sequence & Timing