Chinese Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTEMPORARY CHINA: a BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R Margins 0.9") by Lynn White

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST (Winter 1999 — FIRST ON-LINE EDITION, MS Word, L&R margins 0.9") by Lynn White This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of the seminars WWS 576a/Pol. 536 on "Chinese Development" and Pol. 535 on "Chinese Politics," as well as the undergraduate lecture course, Pol. 362; --to provide graduate students with a list that can help their study for comprehensive exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not too much should be made of this, because some such books may be too old for students' purposes or the subjects may not be central to present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan. Students with specific research topics should definitely meet Laird Klingler, who is WWS Librarian and the world's most constructive wizard. This list cannot cover articles, but computer databases can. Rosemary Little and Mary George at Firestone are also enormously helpful. Especially for materials in Chinese, so is Martin Heijdra in Gest Library (Palmer Hall; enter up the staircase near the "hyphen" with Jones Hall). Other local resources are at institutes run by Chen Yizi and Liu Binyan (for current numbers, ask at EAS, 8-4276). Professional bibliographers are the most neglected major academic resource at Princeton. -

China Agri-Food News Digest Jan 2020

China Agri-food News Digest January 2020 (Total No 85) Be Strong, Wuhan! Be Strong, China! Contents Policies .................................................................................................................. 1 China bans wildlife trade nationwide due to coronavirus outbreak ....................................... 1 China to release vegetable reserves to ensure supply ............................................................ 1 China reveals plan to cut plastic use by 2025 ........................................................................ 1 China issues plan for digital agricultural, rural development ................................................ 1 China plans to issue biosafety certificates to domestic GM soybean, corn ........................... 2 China to strengthen fight against environmental pollution in 2020 ....................................... 2 China to curb farming near rivers in push to reverse water pollution ................................... 2 Extend benefits to farmers to bridge rural-urban divide in a better way ............................... 2 Science, Technology and Environment ............................................................. 3 Chinese drone maker targets farms in Japan, South Korea and Australia ............................. 3 China's Beidou navigation system to provide unique services .............................................. 3 China to step up meteorological efforts in support of agriculture, poverty relief .................. 3 China's major grain producer to further -

6. China's Economic Transformation

6. China’s economic transformation1 Gregory C. Chow Why economic reform started in 1978 Deng Xiaoping took over control of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 1978. He was responsible for initiating reform of the planned economy to move towards a more market-oriented economy. In a sense, the change in policy can be interpreted partially as a continuation of the ‘four modernisations’ (of agriculture, industry, defence, and science and technology) announced by premier Zhou Enlai in 1964, but interrupted by the Cultural Revolution. This explanation was suggested to me by a former vice-premier of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). On the other hand, a former premier once told me: ‘The Cultural Revolution did great harm to China, but it freed us from certain ideological constraints.’ These statements indicate that the Cultural Revolution did affect the thinking of top party leaders and thus the course of China’s economic development. Taking these statements into account, together with other considerations, I offer the following explanation for the initiation of economic reform. There were four reasons the time was ripe for reform. First, the Cultural Revolution was very unpopular, and the party and the government had to distance themselves from the old regime and make changes to win the support of the people. Second, after years of experience in economic planning, government officials understood the shortcomings of the planned system and the need for change. Third, successful economic development in other parts of Asia—including Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea, known as the ‘Four Tigers’—demonstrated to Chinese government officials and the Chinese people that a market economy works better than a planned one. -

Can the Strategy of Western Development Narrow Down China's

Can Western Development Narrow Down China’s Regional Disparity? Can the Strategy of Western Development Narrow Down China’s Regional Disparity?* Wei Zhang Abstract Faculty of Oriental Studies The main causes of the faster growth in China’s eastern coastal University of Cambridge Sidgwick Avenue area, and thus for the rise in income disparity between eastern Cambridge CB3 9AD and western regions, are the rapid increases in foreign trade and United Kingdom foreign investment resulting not only from the government’s [email protected] coastal development strategy but also from inherent advantages of the eastern coastal area. Since 1999, the development strategy for western China has focused on the injection of large amounts of capital, but fiscal constraints make this strategy unsustainable. China’s government should allow mobility of the labor force across regions to play a bigger role in solving the income disparity problem. 1. Introduction China embarked upon economic reforms in 1978. Since then, the average annual growth rate of China’s GDP through 2001 has been 8.9 percent.1 The pace of GDP growth in different regions has varied, however. If we di- vide China into three areas based on geographical location and government policy coverage (viz., eastern, central, * I thank Wing Thye Woo, Cyril Lin, Maozu Lu, Guy Liu, and Zhichao Zhang for insightful discussion on this topic. I also beneªted from discussions during the Asian Economic Panel conference on 9–10 October 2003 in Seoul, South Korea. The views expressed in the paper are those of the author and should not be interpreted as reºecting the views of those who have helped with the paper. -

OECD Reviews of Innovation Policy Synthesis Report

OECD Reviews of Innovation Policy CHINA Synthesis Report ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT in collaboration with THE MINISTRY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, CHINA ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 30 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where govern- ments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice and work to co- ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD. OECD Publishing disseminates widely the results of the Organisation’s statistics gathering and research on economic, social and environmental issues, as well as the conventions, guidelines and standards agreed by its members. © OECD 2007 No reproduction, copy, transmission or translation of this publication may be made without written permission. Applications should be sent to OECD Publishing: [email protected] 3 Foreword This synthesis report (August 2007 Beijing Conference version) summarises the main findings of the OECD review of the Chinese national innovation system (NIS) and policy. -

China's Access to Foreign AI Technology

China’s Access to Foreign AI Technology AN ASSESSMENT 科 AUTHORS Wm. C. Hannas Huey-meei Chang 技 转 SEPTEMBER 2019 移 Established in January 2019, the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) at Georgetown’s Walsh School of Foreign Service is a research organization fo- cused on studying the security impacts of emerging tech- nologies, supporting academic work in security and tech- nology studies, and delivering nonpartisan analysis to the policy community. CSET aims to prepare a generation of policymakers, analysts, and diplomats to address the chal- lenges and opportunities of emerging technologies. During its first two years, CSET will focus on the effects of progress in artificial intelligence and advanced computing. CSET.GEORGETOWN.EDU | [email protected] 2 Center for Security and Emerging Technology SEPTEMBER 2019 China’s Access to Foreign AI Technology AN ASSESSMENT AUTHORS Wm. C. Hannas Huey-meei Changg ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Wm. C. Hannas is author and CSET lead analyst. Huey-meei Chang is contributing author and CSET research analyst. Cover illustration: "Technology transfer" in Chinese. © 2019 Center for Security and Emerging Technology, All rights reserved. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii 1 | INTRODUCTION 1 2 | CHINESE FOREIGN TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER: MYTH AND 3 REALITY 3 | CHINA’S ACCESS TO FOREIGN AI TECHNOLOGY 9 4 | SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS 23 BIBLIOGRAPHY 27 ENDNOTES 29 Center for Security and Emerging Technology i 6 Center for Security and Emerging Technology Executive Summary hina’s technology transfer programs are broad, deeply rooted, and calculated to support the country’s development of artificial C intelligence. These practices have been in use for decades and provide China early insight and access to foreign technical innovations. -

27 the China Factor in Taiwan

Wu Jieh-min, 2016, “The China Factor in Taiwan: Impact and Response”, pp. 425-445 in Gunter Schubert ed., Handbook of T Modern Taiwan Politics and Society, Routledge. 27 THE CHINA FACTOR IN TAIWAN Impact and response Jieh-Min Wu* Since the turn of the century, the rise of China has inspired global a1nbitions and heightened international anxiety. Though Chinese influence is not a ne\V factor in the international geo political syste1n, the synergy between China's growing purchasing po\ver and its political \vill is dra\ving increasing attention on the world stage. With China's e111ergence as a global econontic powerhouse and the Chinese state's extraction of massive revenues and tremendous foreign reserves, Beijing has learned to flex these financial 1nuscles globally in order to achieve its polit ical goals. Essentially, the rise of China has enabled the PRC to speed up its n1ilitary moderniza tion and adroitly co1nbine econonllc measures and 'united front \Vork' in pursuit of its national interests. Hence Taiwan, whose sovereignty continues to be contested by the PRC, has been heavily i1npacted by China's new strategy. The Chinese ca1npaign kno\vn as 'using business to steer politics' has arguably been success ful in achieving inany of the effects desired by Beijing. For exan1ple, the Chinese government has repeatedly leveraged Taiwan's trade and econonllc dependence to intervene in Taiwan's elections. Such econonllc dependence n1ay constrain Taiwanese choices within a structure of Beijing's creation. In son1e historical 1no1nents, however, subjective identity and collect ive action could still en1erge as 'independent variables' that open up \Vindo\vs of opportun ity, expanding the range of available choices. -

'Fear of Probe Led to Curbs on CBI'

Downloaded From:- www.Estore33.com www.Estore33.com https://t.me/TheHindu_Zone_Official follow us: november 18, 2018 Delhi City Edition thehindu.com 42 pages ț ₹15.00 facebook.com/thehindu twitter.com/the_hindu BJP leader K. Surendran Odisha Assembly Vyapam charges have Alexander Zverev stuns taken into preventive accepts the apology no substance, says BJP’s Roger Federer in lastfour custody at Nilackal of Abhijit IyerMitra Vinay Sahasrabuddhe stage of ATP Finals page 8 page 9 page 11 page 17 Printed at . Chennai . Coimbatore . Bengaluru . Hyderabad . Madurai . Noida . Visakhapatnam . Thiruvananthapuram . Kochi . Vijayawada . Mangaluru . Tiruchirapalli . Kolkata . Hubballi . Mohali . Malappuram . Mumbai . Tirupati . lucknow . cuttack . patna NEARBY Delhi Chief Secy. Anshu Ganga waterway project cleared after overruling expert panel Prakash transferred NEW DELHI Delhi Chief Secretary Anshu Environment Ministry and inland the river between Varanasi vancy works. ion Ministry of Environment Prakash, who was allegedly waterways body differed on clearances in Uttar Pradesh and Haldia The ₹5,369 crore project and Forests and the Inland assaulted at Chief Minister in West Bengal. The project is partly funded by the Waterways Authority of In Arvind Kejriwal’s residence in Jacob Koshy try. The latter had recom entails construction of 3 World Bank. However, to en dia (IWAI), which is attached February this year, was NEW DELHI mended public consulta multimodal terminals (Vara able container barges and to the Union Shipping Minis transferred -

China and the SDR Financial Liberalization Through the Back Door

CIGI Papers No. 170 — April 2018 China and the SDR Financial Liberalization through the Back Door Barry Eichengreen and Guangtao Xia CIGI Papers No. 170 — April 2018 China and the SDR: Financial Liberalization through the Back Door Barry Eichengreen and Guangtao Xia CIGI Masthead Executive President Rohinton P. Medhora Deputy Director, International Intellectual Property Law and Innovation Bassem Awad Chief Financial Officer and Director of Operations Shelley Boettger Director of the International Law Research Program Oonagh Fitzgerald Director of the Global Security & Politics Program Fen Osler Hampson Director of Human Resources Susan Hirst Interim Director of the Global Economy Program Paul Jenkins Deputy Director, International Environmental Law Silvia Maciunas Deputy Director, International Economic Law Hugo Perezcano Díaz Director, Evaluation and Partnerships Erica Shaw Managing Director and General Counsel Aaron Shull Director of Communications and Digital Media Spencer Tripp Publications Publisher Carol Bonnett Senior Publications Editor Jennifer Goyder Publications Editor Susan Bubak Publications Editor Patricia Holmes Publications Editor Nicole Langlois Publications Editor Lynn Schellenberg Graphic Designer Melodie Wakefield For publications enquiries, please contact [email protected]. Communications For media enquiries, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2018 by the Centre for International Governance Innovation The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Centre for International Governance Innovation or its Board of Directors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — Non-commercial — No Derivatives License. To view this license, visit (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). For re-use or distribution, please include this copyright notice. -

Involuntary Migrants, Political Revolutionaries and Economic Energisers: a History of the Image of Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia GORDON C

Journal of Contemporary China (2005), 14(42), February, 55–66 Involuntary Migrants, Political Revolutionaries and Economic Energisers: a history of the image of overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia GORDON C. K. CHEUNG* Along the contemporary migration history of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, three distinctive images have been constructed through the interaction between the overseas Chinese and Mainland China. First, the image of involuntary migrant, formulated by their migration activity and the continuous remittance they sent back to their hometowns, closely linked to the political and social-economic disturbances in the early years of the twentieth century. Second, the image of the overseas Chinese as political revolutionary was heavily politicised by the revolutionary policies of Mainland China in the 1950s and 1960s. Third, through the operational means of foreign direct investment, the overseas Chinese image of economic energiser was re-focused and mirror-imaged with the imperative of the economic reform of Mainland China in the 1970s and 1980s. On the one hand, the images of involuntary migrant, political revolutionary and economic energiser of the Southeast Asian overseas Chinese describe their situational status. On the other hand, these images also reflect the contemporary historical development of Mainland China. Whatever the reasons for studying the Overseas Chinese, there is no doubt that they are a bona fide object of research. The diversity of cultures represented by these people, the diversity of settings in which they have found themselves, the wide differences in the histories of specific Chinese ‘colonies’, all of these things make them a fascinating laboratory for social scientists of various disciplinary bents.1 In Southeast Asia the capitalists were the Chinese. -

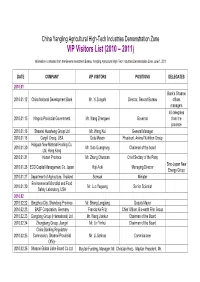

VIP Visitors List (2010 – 2011)

China Yangling Agricultural High-Tech Industries Demonstration Zone VIP Visitors List (2010 – 2011) Information is obtained from the General Investment Bureau, Yangling Agricultural High-Tech Industries Demonstration Zone, June 1, 2011 DATE COMPANY VIP VISITORS POSITIONS DELEGATES 2010.01 Bank's Shaanxi 2010.01.12 China National Development Bank Mr. Yi Zongshi Director, Second Bureau offices managers 40 delegates 2010.01.15 Ningxia Provincial Government Mr. Wang Zhengwei Governor from the province 2010.01.16 Shaanxi Huasheng Group Ltd Mr. Wang Kui General Manager 2010.01.18 Cargill Group, USA Dula Muson President, Animal Nutrition Group Haiguan New Material Holding Co. 2010.01.20 Mr. Xiao Guangrong Chairman of the board Ltd, Hong Kong 2010.01.21 Hunan Province Mr. Zhang Chunxian Chief Sectary of the Party Sino-Japan New 2010.01.26 ECO Capital Management Co. Japan Koji Aoki Managing Director Energy Group 2010.01.27 Department of Agriculture, Thailand Somsak Minister Environmental Microbial and Food 2010.01.30 Mr. Luo Yaguang Senior Scientist Safety Laboratory, USA 2010.02 2010.02.22 Bingzhou City, Shandong Province Mr. Shang Longjiang Deputy Mayor 2010.02.23 BASF Corporation, Germany Francis Ka Fritz Chief Officer, Bio-earth Film Group 2010.02.23 Dongfang Group (International) Ltd Mr. Wang Jiankun Chairman of the Board 2010.02.24 Zhengbang Group, Jiangxi Mr. Lin Yinhui Chairman of the Board China Banking Regulatory 2010.02.25 Commission, Shaanxi Provincial Mr. Li Jianhua Commissioner Office 2010.02.26 Shaanxi Global Jiahe Board Co Ltd Mayfair Funding, Manager: Mr. Christian Herz,Mayfair President: Mr. Rainer Kutzner (Germany), PBH Ltd President: Mr. -

China's Propensity for Innovation in the 21St Century

C O R P O R A T I O N STEVEN W. POPPER, MARJORY S. BLUMENTHAL, EUGENIU HAN, SALE LILLY, LYLE J. MORRIS, CAROLINE S. WAGNER, CHRISTOPHER A. EUSEBI, BRIAN CARLSON, ALICE SHIH China's Propensity for Innovation in the 21st Century Identifying Indicators of Future Outcomes For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA208-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0596-8 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Blackboard/Adobe Stock; RomoloTavani/Getty Images Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions