Prevalence and Clinical Significance of HGV/GBV-C Infection in Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GB Virus C/Hepatitis G Virus Does Not Induce Expression of P44 Antigen in Chimpanzee Hepatocytes Yohko K

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 54, 2001 and skin were removed was purchased on the previous night ongln Of infection was not clear. The food service in a festival of the festival. It was left in the room temperature ovemight. as described in the present case does not requlre regulation The cooking started at 4 0'clock in the momlng by roastlng under the food hyglene law. This incident indicated the the bulk meat by rotation over a gas bumer. The meat was necessity of proper measures for food security in this type of covered by a large steel box during roastlng. It was cut into short temporary food service and regulatory measures in case small pleCeS and served at 10 o'clock in the momlng. Some of possible occurrences of food poISOnlng. noted that some portion of the meat was rare; i.e., it was insufficiently cooked. Laboratory and other epidemiologlCal data will be published ln the outbreak, a total 58 cases were counted. There were in Infectious Agents Surveillance Report, vol. 22 (June, 200 I ). 41 primary infections, 1 1 secondary infections including a We thank the clinical institutions, schools and other institu- case which took place in a nursery school, and 6 cases whose tions fわr their collaboration. Laboratory and Epidemiology Communications GB Virus C/Hepatitis G Virus Does Not Induce Expression of p44 Antigen in Chimpanzee Hepatocytes Yohko K. Shimizu*, Minako Hijikata and Hiroshi Yoshikural Department ofRespiratoyy Diseases, Research Institute, International Medical Center ofJapan, Toyama 1-21-1 Shinjuku-ku, Too,0 162-8655 and JNational Institute ofInfectious Diseases, Toyama 1-23-1, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8640 Communicated by Hiroshi Ybshikura (Accepted June 1, 2001) The cytoplasmic antlgen, p44, was orlglnally discovered found chimpanzees whose sera were positive for GBV-C什IGV in hepatocytes of chimpanzees experimentally infected with RNA by RTIPCR. -

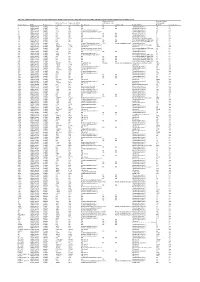

Table S4. Comparison Between the Discvr Results and the BLAST

Table S4. Comparison between the DisCVR results and the BLAST results from the original manuscript for healthy patients and patients with unexplained acute febrile illness Number of k-mers Number of reads Number of k-mers Number of distinct matching the 2nd matching with Sample_Name RUN Patient status matching k-mers matching Top Virus hits hit 2nd Virus Hit Top BLAST hit BLAST Concordance 3 SRR1748140 healthy NA NA NA NA NA Human.adenovirus.C 10 no 4 SRR1748141 healthy NA NA NA NA NA Human.adenovirus.C 65 no 8 SRR1748143 healthy 943 379 Human mastadenovirus C Human.adenovirus.C 65 yes 10 SRR1748147 healthy 1669 133 Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Human.adenovirus.C 26 no 14 SRR1748151 healthy NA NA NA NA NA Human.adenovirus.C 4 no 15 SRR1748152 healthy NA NA NA NA NA Human.adenovirus.C 6 no 108 SRR1748162 healthy NA NA NA NA NA Human.adenovirus.C 6 no 137 SRR1748172 healthy 15343 4714 Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Human.immunodeficiency.virus 314 yes 173 SRR1748173 healthy NA NA NA NA NA Heterosigma.akashiwo.RNA.virus 20 no 245 SRR1748177 healthy NA NA NA NA NA Heterosigma.akashiwo.RNA.virus 17 no 312 SRR1748178 healthy 2843 4 Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 1282 Human mastadenovirus C Human.adenovirus.C 70 no 316 SRR1748179 healthy 22915 5941 Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Human.immunodeficiency.virus 342 yes 319 SRR1748180 healthy 2247683 21201 GB virus C GB.virus.C 20629 yes 325 SRR1748181 healthy 1006 177 Human immunodeficiency virus 1 Heterosigma.akashiwo.RNA.virus 60 no 329 SRR1748182 healthy 1513 124 Human immunodeficiency virus 1 -

GB/Hepatitis G Viruses Likelihood of Secondary Transmission: • Probably Frequent, Based on the Prevalence of Virus in Disease Agent: Blood Donors

APPENDIX 2 GB/Hepatitis G Viruses Likelihood of Secondary Transmission: • Probably frequent, based on the prevalence of virus in Disease Agent: blood donors. • GB viruses (GBV-C/HGV is an acronym for GB virus-C At-Risk Populations: and hepatitis G virus strain variants.) • Blood recipients, injection-drug users, and infants Disease Agent Characteristics: born to infected mothers • Family: Flaviviridae; Genus: Unclassified for GBV-C Vector and Reservoir Involved: • Virion morphology and size: Enveloped, nucleo- capsid of unknown symmetry, 50-100 nm in diameter • Humans • Nucleic acid: Linear, positive-sense, single-stranded Blood Phase: RNA, ~9.4 kb in length • Physicochemical properties: Less stable in CsCl than • Viremic phase can last from weeks to years HCV; other properties not established for these Survival/Persistence in Blood Products: viruses, but, under in vitro conditions, other flavivi- ruses are stable in alkaline environment of pH 8 and • Survives refrigeration are sensitive to treatment with heat, organic solvents, • Inactivated by solvent-detergent and detergents. Transmission by Blood Transfusion: Disease Name: • Well documented in prospective studies • No known disease association Cases/Frequency in Population: Priority Level: • The prevalence of viremia is 1-4%, and antibody • Scientific/Epidemiologic evidence regarding blood prevalence is 3-14% in blood donors. safety: Absent; transmission documented, but no • Prevalence of 10-20% in patients with viral and non- disease associated despite extensive studies viral liver diseases based on antibody and RNA • Public perception and/or regulatory concern regard- • Prevalence of 75-90% in injection-drug users (anti- ing blood safety: Absent body and RNA) • Public concern regarding disease agent: Absent Incubation Period: Background: • Viremia becomes detectable from 2 days to 2 weeks • In the 1960s, serum from a surgeon (GB) with acute postexposure. -

8.3 Notebook Annotated

Hans L. Tillmann, md Department of Gastroenterology, When Two Infections Hepatology, and Endocrinology Diagnostic Laboratory for Viral and Autoimmune Hepatitis Are Better Than One: Medizinische Hochshule Hannover, Germany The Exceptional Role of Summary by Tim Horn Edited by Douglas Dieterich, md, and GB Virus-C (GBV-C) in Stephen Locarnini, mbbs, phd, frc (path) HIV Disease Reprinted from The prn Notebook® | september 2003 | Dr. James F. Braun, Editor-in-Chief | Tim Horn, Executive Editor. | Published in New York City by the Physicians’ Research Network, Inc.® John Graham Brown, Executive Director | For further information and other articles available online, visit http://www.prn.org | All rights reserved. ©september 2003 when it comes to hiv and hepatitis virus coinfections, the pages fected with hcv (Linnen, 1996). A second virus was isolated in this pa- of The prn Notebook have been filled with numerous reports high- tient, which the Genelabs team called the hepatitis G virus (hgv). lighting the distressing prevalence and negative consequences of both With the discovery of both viruses, researchers set out to deter- hepatitis B virus (hbv) and hepatitis C virus (hcv) in hiv-infected in- mine the full genomic sequences of the isolates. It turned out that dividuals. However, it does not appear that all coinfections are harmful. gbv-c and hgv are closely related isolates of the same virus, with more In fact, some may be associated with a significant survival advantage— than 95% sequence homology (Alter, 1996). It was also determined a theory that has many hiv experts both perplexed and excited. that the genomic organization of these viruses is similar to that of hcv gb virus-c (gbv-c) infection is one such example. -

The Breadth of Viruses in Human Semen

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2311.171049 The Breadth of Viruses in Human Semen Technical Appendix Technical Appendix Table. Viruses that are capable of causing viremia and found in human semen* Detection in semen, Isolation from semen Evidence for sexual maximum detection maximum detection transmission within same Virus Family time, d time, d cohort Adenoviruses Adenoviridae AD (1) RCC Unknown Transfusion transmitted virus Anelloviridae NAA (2) No data found Unknown Lassa fever virus† Arenaviridae NAA, 103 (3) RCC, 20 (3) Unknown Rift Valley fever virus† Bunyaviridae NAA, 117 (4) No data found Unknown Ebola virus Filoviridae NAA, 531 (5) RCC, 82 (6) Epi + mol + sem (7) Marburg virus† Filoviridae AD, 83 (8) RAS, 83 (8) Epi + sem (9) GB virus C Flaviviridae NAA (10) No data found Epi + mol (11) Hepatitis C virus Flaviviridae NAA (12); AD (13) No data found Epi + mol (14) Zika virus Flaviviridae NAA, 188 (15) RCC, 7 (16) Epi + mol + sem (17) Hepatitis B virus Hepadnaviridae NAA (18); AD (19) RAS (20) Epi + mol (21) Cytomegalovirus Herpesviridae NAA (22) RCC (23) Epi + mol + sem (24) Epstein Barr virus Herpesviridae NAA (22) No data found Epi and semen (25) Human herpes virus 8 Herpesviridae NAA (26) RCC (27) Epi + mol (28) Human herpes virus 7 Herpesviridae NAA (29) No data found Unknown Human herpes virus 6 Herpesviridae NAA (22) No data found Unknown Human simplex viruses 1 and 2 Herpesviridae NAA (22); AD (1) RCC (1) Epi + mol + sem (30) Varicella zoster virus Herpesviridae NAA (22) No data found Unknown Mumps virus† Paramyxoviridae -

PATHOLOGY of HIV/AIDS 32Nd Edition

PATHOLOGY OF HIV/AIDS 32nd Edition by Edward C. Klatt, MD Professor of Pathology Department of Biomedical Sciences Mercer University School of Medicine Savannah, Georgia, USA July 20, 2021 Copyright © by Edward C. Klatt, MD All rights reserved worldwide 2 DEDICATION To persons living with HIV/AIDS past, present, and future who provide the knowledge, to researchers who utilize the knowledge, to health care workers who apply the knowledge, and to public officials who do their best to promote the health of their citizens with the knowledge of the biology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention of HIV/AIDS. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.................................................................................................................................2 CHAPTER 1 - BIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS OF HIV INFECTION.....6 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................6 BIOLOGY OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS................................................10 HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS SUBTYPES.....................................................29 OTHER HUMAN RETROVIRUSES....................................................................................31 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HIV/AIDS.........................................................................................36 RISK GROUPS FOR HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION.............46 NATURAL HISTORY OF HIV INFECTION......................................................................47 PROGRESSION OF HIV -

Incidence and Influence of GB Virus C and Hepatitis C Virus Infection In

Bone Marrow Transplantation, (1998) 21, 1131–1135 1998 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0268–3369/98 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/bmt Incidence and influence of GB virus C and hepatitis C virus infection in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation H Akiyama1, N Nakamura1, S Tanikawa1, H Sakamaki1, Y Onozawa1, T Shibayama2, S Tanaka2, F Tsuda3, H Okamoto4, Y Miyakawa5 and M Mayumi4 1Hematology Division and 2Liver Unit, Tokyo Metropolitan Komagome Hospital, Tokyo; 3Department of Medical Sciences, Toshiba General Hospital, Tokyo; 4Immunology Division, Jichi Medical School, Tochigi-Ken; and 5Miyakawa Memorial Research Foundation, Tokyo, Japan Summary: bone marrow donors. Since most patients have underlying diseases impairing their immune system and receive mye- Markers of GB virus C (GBV-C) and hepatitis C virus loablative therapies before BMT, infection with hepatitis (HCV) were sought in 80 patients before and after they viruses tends to persist and may induce severe hepatitis. underwent BMT in a metropolitan hospital in Tokyo Furthermore, the infection may be modulated by the adop- between 1990 and 1996. RNA of GBV-C was detected tive immunity transferred by a bone marrow donor who has in 14 (18%) patients before BMT. Of the 55 patients been infected or who has overcome the infection. who had been transfused, 14 (25%) possessed GBV-C Recently, a putative hepatitis virus designated GB virus RNA at a frequency significantly higher than in the 25 C (GBV-C) or hepatitis G virus (HGV) has been disco- untransfused patients who were all negative (P Ͻ 0.01). vered.2,3 For the sake of convenience these are collectively HCV RNA was detected in three of the 55 (5%) trans- referred to here as GBV-C. -

The Genomics of Emerging Pathogens

GG14CH13-Lipkin ARI 1 August 2013 11:16 The Genomics of Emerging Pathogens Cadhla Firth and W. Ian Lipkin Center for Infection and Immunity, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032; email: [email protected], [email protected] Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2013. Keywords 14:281–300 viruses, bacteria, emerging infectious diseases, pathogen discovery by Columbia University on 10/02/13. For personal use only. The Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics is online at genom.annualreviews.org Abstract This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153446 Globalization and industrialization have dramatically altered the vulnerabil- ity of human and animal populations to emerging and reemerging infectious Copyright c 2013 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved diseases while shifting both the scale and pace of disease outbreaks. Fortu- Annu. Rev. Genom. Human Genet. 2013.14:281-300. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org nately, the advent of high-throughput DNA sequencing platforms has also increased the speed with which such pathogens can be detected and charac- terized as part of an outbreak response effort. It is now possible to sequence the genome of a pathogen rapidly, inexpensively, and with high sensitiv- ity, transforming the fields of diagnostics, surveillance, forensic analysis, and pathogenesis. Here, we review advances in methods for microbial discovery and characterization, as well as strategies for testing the clinical and pub- lic health significance of microbe-disease associations. Finally, we discuss how genetic data can inform our understanding of the general process of pathogen emergence. 281 GG14CH13-Lipkin ARI 1 August 2013 11:16 INTRODUCTION Infectious disease research has been transformed by the recent renaissance of the One Health approach, which recognizes the importance of the interrelationships among humans, animals, and the environment in health and disease. -

Appendix 1 – Transmission Electron Microscopy in Virology: Principles, Preparation Methods and Rapid Diagnosis

Appendix 1 – Transmission Electron Microscopy in Virology: Principles, Preparation Methods and Rapid Diagnosis Hans R. Gelderblom Formerly, well-equipped virology institutes possessed many different cell culture types, various ultracentrifuges and even an electron microscope. Tempi passati? Indeed! Meanwhile, molecular biological methods such as polymerase chain reac- tion, ELISA and chip technologies—all fast, highly sensitive detection systems— qualify the merits of electron microscopy within the spectrum of virological methods. Unlike in the material sciences, a significant decline in the use of electron microscopy occurred in life sciences owing to high acquisition costs and lack of experienced personnel. Another reason is the misconception that the use of electron microscopes is expensive and time consuming. However, this does not apply to most conventional methods. The cost of an electron-microscopic preparation, the cost of reagents, contrast and embedding media and the cost of carrier networks are low. Electron microscopy is fast, and for negative staining needs barely 15 min from the start of sample preparation to analysis. Another advantage is that a virtually unlimited number of different samples can be analysed—from nanoparticles to fetid diarrhoea samples. A.1 Principles of Electron Microscopy and Morphological Virus Diagnosis In transmission electron microscopy, accelerated, monochromatic electrons are used to irradiate the object to be imaged. This leads to interactions: the beam electrons are scattered differentially by atomic nuclei and electron shells, losing some of their energy. After magnification through a multistage lens system, a 1,000-fold higher resolution is obtained with a transmission electron microscope than with a light microscope (2 nm vs. -

GB Virusic/Hepatitis G Virus

Jpn. J・ Infect. Dis., 54, 55-63, 2001 Review GB VirusIC/Hepatitis G Virus KenjiAbe* Department of Pathology, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Toyama 1-2311, Shinjuku-ku, Tobo 16218640, Japan (Received January 25, 2001. Accepted April 23, 2001) CONTENTS: Summary lntroduction History Viral genome Mutation rate of the viral genome Diagnostic assay Epidemiology and clinical significance HepatotroplSm and extrahepatic replication of the virus Relation to hepatocellular carcinoma occu汀enCe Experimental infection in chimpanzees C0-infection in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients Existence of viral genotypes and its geographic distribution Conclusion SUMMARY: GB vims-C (GBV-C)仇epatitis G vims (HGV) is a positive, single-strand RNA virus that has been classified in the family Flaviviridae. Interestlngly, GBVIC/HGV appears to have a truncated or absent core protein at the amino teminus of the polyprotein. GBV-C/HGV is transmitted parenterally and probably sexually. Most GBV-C作iGV infections appear to be asymptomatiC, persistent, and no correlation between virus infection and liver dysfunction although the disease-inducing activityof GBV-C什IGV remains to be investigated. Furthermore, there was no evidence ofpathogenesis in the liver by experiment with chimpanzees. From these results, GBV-C/ HGV might be considered as a kind of …orphan" vims in search of a disease. EpidemiologlCal investlgation demonstrated that GBVIC/HGV infection is present in about 1-1.4% of the healthy population in developed countries and in 8- 14.6% in developlng COuntries. The genome of GBV-C/HGV exhibits a sequence variation among different isolates. On the basis of this variation, it has been proposed that GBV-C/HGV can be classified into at least four major genotypes, consisting of type 1 (West Africa), type 2 (US/Europe), type 3 (Asia), andtype 4 (Southeast Asia). -

Supplemental Material.Pdf

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL A cloud-compatible bioinformatics pipeline for ultra-rapid pathogen identification from next-generation sequencing of clinical samples Samia N. Naccache1,2, Scot Federman1,2, Narayanan Veerarghavan1,2, Matei Zaharia3, Deanna Lee1,2, Erik Samayoa1,2, Jerome Bouquet1,2, Alexander L. Greninger4, Ka-Cheung Luk5, Barryett Enge6, Debra A. Wadford6, Sharon L. Messenger6, Gillian L. Genrich1, Kristen Pellegrino7, Gilda Grard8, Eric Leroy8, Bradley S. Schneider9, Joseph N. Fair9, Miguel A.Martinez10, Pavel Isa10, John A. Crump11,12,13, Joseph L. DeRisi4, Taylor Sittler1, John Hackett, Jr.5, Steve Miller1,2 and Charles Y. Chiu1,2,14* Affiliations: 1Department of Laboratory Medicine, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA 2UCSF-Abbott Viral Diagnostics and Discovery Center, San Francisco, CA, USA 3Department of Computer Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA 4Department of Biochemistry, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA 5Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL, USA 6Viral and Rickettsial Disease Laboratory, California Department of Public Health, Richmond, CA, USA 7Department of Family and Community Medicine, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, USA 8Viral Emergent Diseases Unit, Centre International de Recherches Médicales de Franceville, Franceville, Gabon 9Metabiota, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA 10Departamento de Genética del Desarrollo y Fisiología Molecular, Instituto de Biotecnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Cuernavaca, Morelos, México 11Division of Infectious Diseases and International Health and the Duke Global Health -

Hepatitis C-Z: Recent Advances D Kelly, S Skidmore

339 RECENT ADVANCES Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.86.5.339 on 1 May 2002. Downloaded from Hepatitis C-Z: recent advances D Kelly, S Skidmore ............................................................................................................................. Arch Dis Child 2002;86:339–343 In this review, recently identified hepatitis viruses Epidemiology of HCV infection (hepatitis C, hepatitis D, hepatitis E, hepatitis F, hepatitis Prior to the introduction of viral inactivation of blood products and screening of blood for G, transfusion transmissible virus) are described, and anti-HCV in 1991, infection with HCV was found the implications for paediatric liver disease discussed. in those who received blood products or trans- 7 .......................................................................... planted organs. Sporadic cases have also been described, as has nosocomial spread.8 Despite the obvious occupational risk from needle stick he rapid development of molecular tech- accidents, the prevalence of HCV among health niques has lead to the discovery of a number care workers in the UK is no higher than in blood Tof hepatotrophic viruses, but little clarity donors, which is related to the low prevalence of about their significance or long term outcome. HCV generally.910 Paediatricians now need an understanding of Currently the main source of infection is which hepatitis viruses are significant in clinical among intravenous drug abusers,11 which has practice, how to handle them, and when to refer particular relevance