Effects of Soil Texture and Groundwater Level on Leaching of Salt from Saline Fields in Kesem Irrigation Scheme, Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Soil Science W

Basic Soil Science W. Lee Daniels See http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/430/430-350/430-350_pdf.pdf for more information on basic soils! [email protected]; 540-231-7175 http://www.cses.vt.edu/revegetation/ Well weathered A Horizon -- Topsoil (red, clayey) soil from the Piedmont of Virginia. This soil has formed from B Horizon - Subsoil long term weathering of granite into soil like materials. C Horizon (deeper) Native Forest Soil Leaf litter and roots (> 5 T/Ac/year are “bio- processed” to form humus, which is the dark black material seen in this topsoil layer. In the process, nutrients and energy are released to plant uptake and the higher food chain. These are the “natural soil cycles” that we attempt to manage today. Soil Profiles Soil profiles are two-dimensional slices or exposures of soils like we can view from a road cut or a soil pit. Soil profiles reveal soil horizons, which are fundamental genetic layers, weathered into underlying parent materials, in response to leaching and organic matter decomposition. Fig. 1.12 -- Soils develop horizons due to the combined process of (1) organic matter deposition and decomposition and (2) illuviation of clays, oxides and other mobile compounds downward with the wetting front. In moist environments (e.g. Virginia) free salts (Cl and SO4 ) are leached completely out of the profile, but they accumulate in desert soils. Master Horizons O A • O horizon E • A horizon • E horizon B • B horizon • C horizon C • R horizon R Master Horizons • O horizon o predominantly organic matter (litter and humus) • A horizon o organic carbon accumulation, some removal of clay • E horizon o zone of maximum removal (loss of OC, Fe, Mn, Al, clay…) • B horizon o forms below O, A, and E horizons o zone of maximum accumulation (clay, Fe, Al, CaC03, salts…) o most developed part of subsoil (structure, texture, color) o < 50% rock structure or thin bedding from water deposition Master Horizons • C horizon o little or no pedogenic alteration o unconsolidated parent material or soft bedrock o < 50% soil structure • R horizon o hard, continuous bedrock A vs. -

Land Use Change, Modelling of Soil Salinity And

KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI, GHANA LAND USE CHANGE, MODELLING OF SOIL SALINITY AND HOUSEHOLDS’ DECISIONS UNDER CLIMATE CHANGE SCENARIOS IN THE COASTAL AGRICULTURAL AREA OF SENEGAL BY Sophie THIAM (BSc. Natural Sciences, MSc. Natural Resources Management and Sustainable Development) A Thesis submitted to the Department of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Climate Change and Land Use June, 2019 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the PhD in Climate Change and Land Use and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person, nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgment has been made in the text. Sophie Thiam (PG7281816) Signature…………………Date………………... Certified by: Prof. Nicholas Kyei-Baffour Signature…………….…….Date……………… Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (Supervisor) Dr. François Matty Signature................................Date………… Institut des Sciences De l’Environnement University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar (Supervisor) Dr. Grace B.Villamor Signature………………….Date…………… Centre for Resilience Communities University of Idaho (Supervisor) Prof. Samuel Nii Odai Signature………………..Date………………. Head of Department of Civil Engineering i ABSTRACT Soil salinity remains one of the most severe environmental problems in the coastal agricultural areas in Senegal. It reduces crop yields thereby endangering smallholder farmers’ livelihood. To support effective land management, especially in coastal areas where impacts of climate change have induced soil salinity and food insecurity, this study investigated the patterns and impacts of soil salinity in a coastal agricultural landscape by developing an Agent-Based Model (ABM) for Djilor District, Fatick Region, Senegal. -

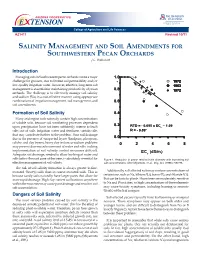

Salinity Management and Soil Amendments for Southwestern Pecan Orchards J.L

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION College of Agriculture and Life Sciences AZ1411 Revised 10/11 SALINITY MANAGEMENT AND SOIL AMENDMENTS FOR SOUTHWESTERN PECAN ORCHARDS J.L. Walworth Introduction Managing salts in Southwestern pecan orchards can be a major 1.0 challenge for growers, due to limited soil permeability and/or 1219721972 low-quality irrigation water. However, effective, long-term salt 1319631963 management is essential for maintaining productivity of pecan 0.8 1219721972 orchards. The challenge is to effectively manage soil salinity and sodium (Na) in a cost-effective manner, using appropriate combinations of irrigation management, soil management, and 0.6 soil amendments. Formation of Soil Salinity 0.4 Many arid region soils naturally contain high concentrations of soluble salts, because soil weathering processes dependent 0.2 upon precipitation have not been sufficiently intense to leach RTD = -0.095 x ECe –1.09 salts out of soils. Irrigation water and fertilizers contain salts R = -0.89** that may contribute further to the problem. Poor soil drainage due to the presence of compacted layers (hardpans, plowpans, 0.0 caliche, and clay lenses), heavy clay texture, or sodium problems 0022446688 may prevent downward movement of water and salts, making implementation of soil salinity control measures difficult. ECe (dS/m) Adequate soil drainage, needed to allow leaching of water and salts below the root zone of the trees, is absolutely essential for Figure 1. Reduction in pecan relative trunk diameter with increasing soil effective management of soil salinity. salt concentrations. After Miyamoto, et al., Irrig. Sci. (1986) 7:83-95. The risk of soil salinity formation is always greater in fine- textured (heavy) soils than in coarse-textured soils. -

Pages 406 To

397 SOIL SALINITY CONTROL UNDER BARLEY CULTIVATION USING A LABORATORY DRY DRAINAGE MODEL Shahab Ansari 1,*, Behrouz Mostafazadeh-Fard 2, Jahangir Abedi Koupai3 Abstract The drainage of agricultural fields is carried out in order to control soil salinity and the water table. Conventional drainage methods such as lateral drainage and interceptor drains have been used for many years. These methods increase agriculture production; but they are expensive and often cause environmental contaminations. One of the inexpensive and more environmental friendly methods that can be used in arid and semi-arid regions to remove excess salts from irrigated lands to non- irrigated or fallow lands is dry drainage. In the dry drainage method, natural soil system and the evaporation of fallow land is used to control soil salinity and the water table of irrigated land. There are few studies about dry drainage concepts. it is also important to study soil salt changes over time because of salt movements from irrigated areas to non-irrigated areas especially under plant cultivation. In this study a laboratory model which is able to simulate dry drainage was used to investigate soil salts transport under barley cultivation. The model was studied during the barley growing season and for a constant water table. During the growing season soil salinities of irrigated and non-irrigated areas were measured at different time. The Results showed that dry drainage can control the soil salinity of an irrigated area. The excess salts leached from an irrigated area and accumulated in the non-irrigated area and the leaching rate changed over time. -

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

Design & Development of Automatic Soil Salinity Control System

International Journal of Latest Trends in Engineering and Technology (IJLTET) Design & Development of Automatic Soil Salinity Control System Praveen Kumar Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering MVN University, Palwal, Haryana, India Dr. S. K. Luthra Vice Chancellor MVN University, Palwal, Haryana India Dr. Rajeev Ratan Head of Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering MVN University, Palwal, Haryana India Abstract - The main objective of this project is to control soil salinity and improve soil fertility. The word salinity defines amount of salt present in water or soil which tends to decrease soil fertility through natural or human induced processes that results in the accumulation of dissolved salt in the soil water to an extent that inhibits plant growth and salinity is a severe environmental hazards that degrades the growth of many crops Spatial characterization of soil salinity is required for establishing salt control measurements in irrigated agriculture. For that, cost-effective, specific, rapid, and reliable methodologies for determining soil salinity in-situ and processing those data are required. Keywords: Microcontroller AT89S52, Soil Salinity, Salinity Sensor, salinity control I. INTRODUCTION Salinity means amount of salt in water and soil . soil salinity means unwanted amount of salt present in soil .As population is increasing so demands of food increasing ,soil salinity degrads quality of food availability in market. The accumulated salts include sodium , potassium, magnesium, calcium, chloride, sulphate, carbonate and bicarbonate. primary salinization involves salt accumulation through natural process due to high salt containment in ground water , whereas in secondary salinization is due to human interventions such as inappropriate irrigation procedure e.g with salt rich irrigation water. -

Soil Texture Chart Chart the Soil Texture Chart Gives Names Associated with Various Combinations of Sand, Silt and Clay and Is Used to Classify the Texture of a Soil

Name: _________________________________ Soil Texture Directions: Read, highlight, and answer the schoology questions. Until now, we have spent our time defining soil. We know that soil comes from broken down rocks and minerals that have been weathered both mechanically and chemically. We also know that soil contains a variety of parts consisting of sand, soil, clay, and humus. But what is the best soil? I’m sure you are saying loam is the best. You are right, but what exactly is loam? To understand loam, we need to understand how three parts of soil come together. If I were to ask you to draw soil, it would probably look like the image to the right. Most would just draw a pile of dirt. As we are learning though, soil is much more complex than that. Sand, Silt and Clay One of the key ways that we characterize rocks is by texture. Remember that texture refers to how something feels. It can feel grainy, rough, or smooth. Larger particles feel rough while smaller particles feel smooth. For soil, we also use texture to help characterize the type. The texture of soil, just like rocks, refers to the size of the particles that make up the soil. The terms sand, silt, and clay refer to different sizes of the soil particles. Sand, being the larger size of particles, feels gritty. Silt, being moderate in size, has a smooth or floury texture. Clay, being the smaller size of particles, feels sticky. Look at the figure to the right. The size of the circle is relative to each size particle. -

Evaluation of Subsurface Drainage Techniques Used for Dryland Salinity

EVALUATION OF SUBSURFACE DRAINAGE TECHNIQUES USED FOR DRYLAND SALINITY CONTROL A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the Degree ofMaster ofScience in the Division ofEnvironmental Engineering University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon By Warren Douglas Helgason Fall 2000 © Copyright Warren Douglas Helgason, 2000. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University ofSaskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree permission for copYing ofthis thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head ofthe Department or the Dean ofthe College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any coPYing or publication or use ofthis thesis or parts thereoffor financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which be made ofany material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use ofmaterial in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Chair ofthe Division ofEnvironmental Engineering University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, sm 5A9 1 DATA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND RESTRICTIONS All raw data used in this study dated prior to 1997 were collected by the staffat Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada's Semiarid Prairie Agricultural Research Centre (SPARC) in Swift Current, Saskatchewan. -

Unit 2.3, Soil Biology and Ecology

2.3 Soil Biology and Ecology Introduction 85 Lecture 1: Soil Biology and Ecology 87 Demonstration 1: Organic Matter Decomposition in Litter Bags Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 101 Step-by-Step Instructions for Students 103 Demonstration 2: Soil Respiration Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 105 Step-by-Step Instructions for Students 107 Demonstration 3: Assessing Earthworm Populations as Indicators of Soil Quality Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 111 Step-by-Step Instructions for Students 113 Demonstration 4: Soil Arthropods Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 115 Assessment Questions and Key 117 Resources 119 Appendices 1. Major Organic Components of Typical Decomposer 121 Food Sources 2. Litter Bag Data Sheet 122 3. Litter Bag Data Sheet Example 123 4. Soil Respiration Data Sheet 124 5. Earthworm Data Sheet 125 6. Arthropod Data Sheet 126 Part 2 – 84 | Unit 2.3 Soil Biology & Ecology Introduction: Soil Biology & Ecology UNIT OVERVIEW MODES OF INSTRUCTION This unit introduces students to the > LECTURE (1 LECTURE, 1.5 HOURS) biological properties and ecosystem The lecture covers the basic biology and ecosystem pro- processes of agricultural soils. cesses of soils, focusing on ways to improve soil quality for organic farming and gardening systems. The lecture reviews the constituents of soils > DEMONSTRATION 1: ORGANIC MATTER DECOMPOSITION and the physical characteristics and soil (1.5 HOURS) ecosystem processes that can be managed to In Demonstration 1, students will learn how to assess the improve soil quality. Demonstrations and capacity of different soils to decompose organic matter. exercises introduce students to techniques Discussion questions ask students to reflect on what envi- used to assess the biological properties of ronmental and management factors might have influenced soils. -

Soil Carbon Losses Due to Increased Cloudiness in a High Arctic Tundra Watershed (Western Spitsbergen)

SOIL CARBON LOSSES DUE TO INCREASED CLOUDINESS IN A HIGH ARCTIC TUNDRA WATERSHED (WESTERN SPITSBERGEN) Christoph WŸthrich 1, Ingo Mšller 2 and Dietbert Thannheiser2 1. Department of Geography, University of Basel, Spalenring 145, CH-4055 Basel, Switzerland; e-mail: [email protected]. 2. Department of Geography, University of Hamburg, Bundesstr. 55, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany. Abstract Carbon pool and carbon flux measurements of different habitats were made in the high Arctic coastal tundra of Spitsbergen. The studied catchment was situated on the exposed west coast, where westerly winds produce daily precipitation in form of rain, drizzle and fog. The storage of organic carbon in the catchment of Eidembukta amounts to 5.98 kg C m-2, mainly within the lower horizons of deep soils. Between 5.2 - 23.6 % of the carbon pool is stored in plant material. During the cold and cloudy summer of 1996, net CO2 flux measure- ments showed carbon fluxes from soil to atmosphere even during the brightest hours of the day. We estimate -2 -1 that the coastal tundra of Spitsbergen lost carbon at a rate of 0.581 g C m d predominantly as CO2-C. Carbon loss (7.625 mg C m-2 d-1) as TOC in small tundra rivers accounts only for a small proportion (1.31 %) of the total carbon loss. Introduction tetragona, Betula nana, and Empetrum hermaphroditum might accompany warming on Spitsbergen (WŸthrich, Large terrestrial carbon pools are found in the peat- 1991; Thannheiser, 1994; Elvebakk and Spjelkavik, lands of the boreal and subpolar zones that cover in 1995). -

Part 618 – Soil Properties and Qualities

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 618 – Soil Properties and Qualities Subpart B – Exhibits 618.80 Guides for Estimating Risk of Corrosion Potential for Uncoated Steel Property Limits Low Moderate High •Very deep internal free water •Very deep internal free water •Very deep internal free Internal free water occurrence (or excessively occurrence (or well drained) water occurrence (or well occurrence class (or drained to well drained) coarse moderately fine textured soils; or drained) fine textured or drainage class) and general to medium textured soils; or •Deep internal free water stratified soils; or texture group 1/ 2/ •Deep internal free water occurrence (or moderately well •Deep internal free water occurrence (or moderately well drained) moderately coarse and occurrence (or moderately drained) coarse textured soils; medium textured soils; or well drained) moderately fine or •Moderately deep internal free and fine textured or stratified •Moderately deep internal free water occurrence (or somewhat soils; or water occurrence (or somewhat poorly drained) moderately •Moderately deep internal poorly drained) coarse textured coarse textured soils; or free water occurrence (or soils •Very shallow internal free water somewhat poorly drained) occurrence (or very poorly medium to fine textured or drained) soils with a stable high stratified soils; or water table •Shallow or very shallow internal free water occurrence (or poorly or very poorly drained) soils with a fluctuating water table Total acidity (cmol(+)/kg-1) <10 10-25 >25 3/ 4/ Conductivity of saturated <1 1-4 >4 extract (dS/m-1) 3/ 5/ 4-10 for saturated soils 6/ >10 for saturated soils 6/ Resistivity at saturation >5,000 2,000-5,000 <2,000 (ohm/cm) 1/ 7/ 1/ Based on data in the publication "Underground Corrosion," table 99, p.167, Circular 579, U.S. -

Salinity Management for Sustainable Irrigation Integratingscience, Environment, and Economics Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

ENVIRONMENTALLY AND SOCIALLY SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT 1~~U) Rural Development Work in progresS 20842 for public discussion August 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized Salinity Management for Sustainable Irrigation IntegratingScience, Environment, and Economics Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized f~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~i:2 Public Disclosure Authorized Daniel Hillel wit/ an appendix by E. Feinerman ENVIRONMENTALLY AND SOCIALLY SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Rural Development Salinity Management for Sustainable Irrigation IntegratingScience, Enzvronment, and Economics DanielHillel withan appendixby E. Feinerman The WorldBank Washington,D.C. Copyright (©2000 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing August 2000 12340403020100 This report has been prepared by the staff of the World Bank. The judgments expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors or of the govermnents they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other in- formation shown on any map in this volume do not imply on the part of the World Bank Group any judg- ment on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. Permission to photocopy items for internal or personal use, for the internal or personal use of specific clients, or for educational classroom use, is granted by the World Bank, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, U.S.A., telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470.