Triassic and Jurassic Rocks of the Albuquerque Area Clay T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy Of

Triassic- Jurassic Stratigraphy of the <JF C7 JL / Culpfeper and B arbour sville Basins, VirginiaC7 and Maryland/ ll.S. PAPER Triassic-Jurassic Stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville Basins, Virginia and Maryland By K.Y. LEE and AJ. FROELICH U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1472 A clarification of the Triassic--Jurassic stratigraphic sequences, sedimentation, and depositional environments UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1989 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, Jr., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Lee, K.Y. Triassic-Jurassic stratigraphy of the Culpeper and Barboursville basins, Virginia and Maryland. (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1472) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. no. : I 19.16:1472 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Triassic. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic Jurassic. 3. Geology Culpeper Basin (Va. and Md.) 4. Geology Virginia Barboursville Basin. I. Froelich, A.J. (Albert Joseph), 1929- II. Title. III. Series. QE676.L44 1989 551.7'62'09755 87-600318 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.......................................................................................................... 1 Stratigraphy Continued Introduction... .......................................................................................... -

Ron Blakey, Publications (Does Not Include Abstracts)

Ron Blakey, Publications (does not include abstracts) The publications listed below were mainly produced during my tenure as a member of the Geology Department at Northern Arizona University. Those after 2009 represent ongoing research as Professor Emeritus. (PDF) – A PDF is available for this paper. Send me an email and I'll attach to return email Blakey, R.C., 1973, Stratigraphy and origin of the Moenkopi Formation of southeastern Utah: Mountain Geologist, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 1 17. Blakey, R.C., 1974, Stratigraphic and depositional analysis of the Moenkopi Formation, Southeastern Utah: Utah Geological Survey Bulletin 104, 81 p. Blakey, R.C., 1977, Petroliferous lithosomes in the Moenkopi Formation, Southern Utah: Utah Geology, vol. 4, no. 2, p. 67 84. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Oil impregnated carbonate rocks of the Timpoweap Member Moenkopi Formation, Hurricane Cliffs area, Utah and Arizona: Utah Geology, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 45 54. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Stratigraphy of the Supai Group (Pennsylvanian Permian), Mogollon Rim, Arizona: in Carboniferous Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon Country, northern Arizona and southern Nevada, Field Trip No. 13, Ninth International Congress of Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology, p. 89 109. Blakey, R.C., 1979, Lower Permian stratigraphy of the southern Colorado Plateau: in Four Corners Geological Society, Guidebook to the Permian of the Colorado Plateau, p. 115 129. (PDF) Blakey, R.C., 1980, Pennsylvanian and Early Permian paleogeography, southern Colorado Plateau and vicinity: in Paleozoic Paleogeography of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section, Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists, p. 239 258. Blakey, R.C., Peterson, F., Caputo, M.V., Geesaman, R., and Voorhees, B., 1983, Paleogeography of Middle Jurassic continental, shoreline, and shallow marine sedimentation, southern Utah: Mesozoic PaleogeogÂraphy of west central United States, Rocky Mountain Section of Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists (Symposium), p. -

Cyclicity, Dune Migration, and Wind Velocity in Lower Permian Eolian Strata, Manitou Springs, CO

Cyclicity, Dune Migration, and Wind Velocity in Lower Permian Eolian Strata, Manitou Springs, CO by James Daniel Pike, B.S. A Thesis In Geology Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCES Approved Dustin E. Sweet Chair of Committee Tom M. Lehman Jeffery A. Lee Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School August, 2017 Copyright 2017, James D. Pike Texas Tech University, James Daniel Pike, August 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my greatest thanks to my advisor Dr. Dustin Sweet, who was an excellent advisor during this research. Dr. Sweet was vital throughout the whole process, be it answering questions, giving feedback on figures, and imparting his extensive knowledge of the ancestral Rocky Mountains on me; for this I am extremely grateful. Dr. Sweet allowed me to conduct my own research without looking over my shoulder, but was always available when needed. When I needed a push, Dr. Sweet provided it. I would like to thank my committee memebers, Dr. Lee and Dr. Lehman for providing feedback and for their unique perspectives. I would like to thank Jenna Hessert, Trent Jackson, and Khaled Chowdhury for acting as my field assistants. Their help in taking measurements, collecting samples, recording GPS coordinates, and providing unique perspectives was invaluable. Thank you to Melanie Barnes for allowing me to use her lab, and putting up with the mess I made. This research was made possible by a grant provided by the Colorado Scientific Society, and a scholarship provided by East Texas Geological Society. -

Distribution of Elements in Sedimentary Rocks of the Colorado Plateau a Preliminary Report

Distribution of Elements in Sedimentary Rocks of the Colorado Plateau A Preliminary Report GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1107-F Prepared on behalf of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Distribution of Elements in Sedimentary Rocks of the Colorado Plateau A Preliminary Report By WILLIAM L. NEWMAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GEOLOGY OF URANIUM GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1107-F Prepared on behalf of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. WASHINGTON : 1962 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D.G. CONTENTS Page Abstract____________________________-__-__-_---_-___-___ 337 Introduction ______________________________________________________ 339 Physical features of sedimentary rocks------_--__----_------------__- 339 Precambrian sedimentary rocks.________________________________ 341 Cambrian system____________________________________________ 342 Ordovician system..___________________________________________ 344 Devonian system._____________________________________________ 344 Mississippian system.._________________________________________ 346 Pennsylvanian system________________________________________ 346 Permian system _______________________________________________ 349 Triassic system______________________________________________ 352 Moenkopi formation _______________________________________ 352 Chinle formation..._______________________________________ -

Rock Layers of the Monument

ROCK LAYERS OF THE MONUMENT The rocks of Colorado National Monument record a fascinating story of mountain building, enormous amounts of erosion, and changing climates, as the continent of North America gradually moved northward toward its present position. PRECAMBRIAN The dark-colored rock at the bottom of the with the overlying red sedimentary rocks. canyons is Precambrian in age, dated at The record of about 1.5 billion years of 1. 7 billion years old. These rocks were earth's history is missing! We know from originally sedimentary rocks, but were surrounding areas that this region was changed into metamorphic rocks and partly uplifted into a major mountain range which, melted into igneous rocks when the area that after hundreds of millions of years, was is now Colorado collided with ancient finally eroded low enough that sediments North America and became part of the could be deposited where the mountains continent. There is a huge gap in the once stood. geologic record at the contact of these rocks The lowest and oldest layer of sedimentary deposits, the Chinle Formation records a TRIASSIC rock is the Chinle Formation. Comprised time when this area was close to the equator. chiefly of red stream and floodplain JURASSIC As the continent slowly drifted northward, After Entrada time, a succession of lake and the climate changed and desert conditions stream deposits formed, beginning with the prevailed. The towering cliffs of the wind Wanakah Formation and followed by the deposited (eolian) Wingate Sandstone Morrison Formation. preserve the remnants of sand dunes Here at Colorado National Monument, the formed in that desert. -

The Moenave Formation: Sedimentologic and Stratigraphic Context of the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary in the Four Corners Area, Southwestern U.S.A

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 244 (2007) 111–125 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo The Moenave Formation: Sedimentologic and stratigraphic context of the Triassic–Jurassic boundary in the Four Corners area, southwestern U.S.A. ⁎ Lawrence H. Tanner a, , Spencer G. Lucas b a Department of Biology, Le Moyne College, 1419 Salt Springs Road, Syracuse, NY 13214, USA b New Mexico Museum of Natural History, 1801 Mountain Road, N.W., Albuquerque, NM 87104, USA Received 20 February 2005; accepted 20 June 2006 Abstract The Moenave Formation was deposited during latest Triassic to earliest Jurassic time in a mosaic of fluvial, lacustrine, and eolian subenvironments. Ephemeral streams that flowed north-northwest (relative to modern geographic position) deposited single- and multi-storeyed trough cross-bedded sands on an open floodplain. Sheet flow deposited mainly silt across broad interchannel flats. Perennial lakes, in which mud, silt and carbonate were deposited, formed on the terminal floodplain; these deposits experienced episodic desiccation. Winds that blew dominantly east to south-southeast formed migrating dunes and sand sheets that were covered by low-amplitude ripples. The facies distribution varies greatly across the outcrop belt. The lacustrine facies of the terminal floodplain are limited to the northern part of the study area. In a southward direction along the outcrop belt (along the Echo Cliffs and Ward Terrace in Arizona), dominantly fluvial–lacustrine and subordinate eolian facies grade mainly to eolian dune and interdune facies. This transition records the encroachment of the Wingate erg. Moenave outcrops expose a north–south lithofacies gradient from distal, (erg margin) to proximal (erg interior). The presence of ephemeral stream and lake deposits, abundant burrowing and vegetative activity, and the general lack of strongly developed aridisols or evaporites suggest a climate that was seasonally arid both before and during deposition of the Moenave and the laterally equivalent Wingate Sandstone. -

Tetrapod Biostratigraphy and Biochronology of the Triassic–Jurassic Transition on the Southern Colorado Plateau, USA

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 244 (2007) 242–256 www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Triassic–Jurassic transition on the southern Colorado Plateau, USA Spencer G. Lucas a,⁎, Lawrence H. Tanner b a New Mexico Museum of Natural History, 1801 Mountain Rd. N.W., Albuquerque, NM 87104-1375, USA b Department of Biology, Le Moyne College, 1419 Salt Springs Road, Syracuse, NY 13214, USA Received 15 March 2006; accepted 20 June 2006 Abstract Nonmarine fluvial, eolian and lacustrine strata of the Chinle and Glen Canyon groups on the southern Colorado Plateau preserve tetrapod body fossils and footprints that are one of the world's most extensive tetrapod fossil records across the Triassic– Jurassic boundary. We organize these tetrapod fossils into five, time-successive biostratigraphic assemblages (in ascending order, Owl Rock, Rock Point, Dinosaur Canyon, Whitmore Point and Kayenta) that we assign to the (ascending order) Revueltian, Apachean, Wassonian and Dawan land-vertebrate faunachrons (LVF). In doing so, we redefine the Wassonian and the Dawan LVFs. The Apachean–Wassonian boundary approximates the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. This tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology of the Triassic–Jurassic transition on the southern Colorado Plateau confirms that crurotarsan extinction closely corresponds to the end of the Triassic, and that a dramatic increase in dinosaur diversity, abundance and body size preceded the end of the Triassic. © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Triassic–Jurassic boundary; Colorado Plateau; Chinle Group; Glen Canyon Group; Tetrapod 1. Introduction 190 Ma. On the southern Colorado Plateau, the Triassic– Jurassic transition was a time of significant changes in the The Four Corners (common boundary of Utah, composition of the terrestrial vertebrate (tetrapod) fauna. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

GEOLOGY and GROUND-WATER SUPPLIES of the FORT WINGATE INDIAN SCHOOL AREA, Mckinley COUNTY, NEW MEXICO

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 360 GEOLOGY AND GROUND-WATER SUPPLIES OF THE FORT WINGATE INDIAN SCHOOL AREA, McKINLEY COUNTY, NEW MEXICO PROPERTY OT§ tJ. B. EED! DGJCAL' SURVEY PUBLIC INQUIRIES OFFICE BAN FRANC1ECQ. CALIFORNIA Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Indian Affairs UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 360 GEOLOGY AND GROUND-WATER SUPPLIES OF THE FORT WINGATE INDIAN SCHOOL AREA, McKINLEY COUNTY, NEW MEXICO By J. T. Callahan and R. L. Cushman Prepared in cooperation with the Bureau of Indian Affairs Washington, D. C-, 1905 Free on application to the Geological Survey, Washington 25, D. C. GEOLOGY AND GROUND-WATER SUPPLIES OF THE FORT WINGATE INDIAN SCHOOL AREA, McKINLEY COUNTY, NEW MEXICO By J. T. Callahan and R. L. Cushman CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.................................................... 1 Geology and ground-water resources--Continued Introduction............................................... 2 Geologic structures--Continued Location, topography, and drainage............... 2 Faults..,................................................. 5 Geology and ground-water resources.............. 2 Ground water................................................ 5 Geologic formations and their water-bearing San Andres formation.................................. 5 properties........................................ 2 Recharge conditions................................. 5 Permian system................................... 4 Discharge -

Geology and Stratigraphy Column

Capitol Reef National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Geology “Geology knows no such word as forever.” —Wallace Stegner Capitol Reef National Park’s geologic story reveals a nearly complete set of Mesozoic-era sedimentary layers. For 200 million years, rock layers formed at or near sea level. About 75-35 million years ago tectonic forces uplifted them, forming the Waterpocket Fold. Forces of erosion have been sculpting this spectacular landscape ever since. Deposition If you could travel in time and visit Capitol Visiting Capitol Reef 180 million years ago, Reef 245 million years ago, you would not when the Navajo Sandstone was deposited, recognize the landscape. Imagine a coastal you would have been surrounded by a giant park, with beaches and tidal flats; the water sand sea, the largest in Earth’s history. In this moves in and out gently, shaping ripple marks hot, dry climate, wind blew over sand dunes, in the wet sand. This is the environment creating large, sweeping crossbeds now in which the sediments of the Moenkopi preserved in the sandstone of Capitol Dome Formation were deposited. and Fern’s Nipple. Now jump ahead 20 million years, to 225 All the sedimentary rock layers were laid million years ago. The tidal flats are gone and down at or near sea level. Younger layers were the climate supports a tropical jungle, filled deposited on top of older layers. The Moenkopi with swamps, primitive trees, and giant ferns. is the oldest layer visible from the visitor center, The water is stagnant and a humid breeze with the younger Chinle Formation above it. -

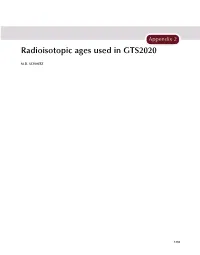

Schmitz, M. D. 2000. Appendix 2: Radioisotopic Ages Used In

Appendix 2 Radioisotopic ages used in GTS2020 M.D. SCHMITZ 1285 1286 Appendix 2 GTS GTS Sample Locality Lat-Long Lithostratigraphy Age 6 2s 6 2s Age Type 2020 2012 (Ma) analytical total ID ID Period Epoch Age Quaternary À not compiled Neogene À not compiled Pliocene Miocene Paleogene Oligocene Chattian Pg36 biotite-rich layer; PAC- Pieve d’Accinelli section, 43 35040.41vN, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 42.3 m above base of 26.57 0.02 0.04 206Pb/238U B2 northeastern Apennines, Italy 12 29034.16vE section Rupelian Pg35 Pg20 biotite-rich layer; MCA- Monte Cagnero section (Chattian 43 38047.81vN, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 145.8 m above base 31.41 0.03 0.04 206Pb/238U 145.8, equivalent to GSSP), northeastern Apennines, Italy 12 28003.83vE of section MCA/84-3 Pg34 biotite-rich layer; MCA- Monte Cagnero section (Chattian 43 38047.81vN, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 142.8 m above base 31.72 0.02 0.04 206Pb/238U 142.8 GSSP), northeastern Apennines, Italy 12 28003.83vE of section Eocene Priabonian Pg33 Pg19 biotite-rich layer; MASS- Massignano (Oligocene GSSP), near 43.5328 N, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 14.7 m above base of 34.50 0.04 0.05 206Pb/238U 14.7, equivalent to Ancona, northeastern Apennines, 13.6011 E section MAS/86-14.7 Italy Pg32 biotite-rich layer; MASS- Massignano (Oligocene GSSP), near 43.5328 N, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 12.9 m above base of 34.68 0.04 0.06 206Pb/238U 12.9 Ancona, northeastern Apennines, 13.6011 E section Italy Pg31 Pg18 biotite-rich layer; MASS- Massignano (Oligocene GSSP), near 43.5328 N, Scaglia Cinerea Fm, 12.7 m above base of 34.72 0.02 0.04 206Pb/238U -

Lexique Stratigraphique Canadien - Volume V-B - Region Des Appalaches, Des Basses-Terres Du Saint-Laurent Et Des Iles De La Madeleine Lexique Stratigraphique

DV 91-23 LEXIQUE STRATIGRAPHIQUE CANADIEN - VOLUME V-B - REGION DES APPALACHES, DES BASSES-TERRES DU SAINT-LAURENT ET DES ILES DE LA MADELEINE LEXIQUE STRATIGRAPHIQUE CANADIEN Volume Fa Région des Appalaches, des Basses-Terres du Saint-Laurent et des îles de la Madeleine par Yvon Globensky et collaborateurs 1993 Québec ©© LEXIQUE STRATIGRAPHIQUE CANADIEN Volume r-8 Région des Appalaches, des Basses-Terres du Saint-Laurent et des Îles de la Madeleine par Yvon Globensky et collaborateurs DV 91-23 1993 Quebec ®® DIRECTION GÉNÉRALE DE L'EXPLORATION GÉOLOGIQUE ET MINÉRALE Sous-ministre adjoint: R.Y. Lamarche DIRECTION DE LA RECHERCHE GÉOLOGIQUE Directeur: A. Simard, par intérim SERVICE GÉOLOGIQUE DE QUÉBEC Chef: J.-M. Charbonneau Manuscrit soumis le: 30-01-91 Accepté pour publication le: 14-06-91 Lecteur critique J. Béland Édition Géomines / F. Dompierre Préparé par la Division de l'édition (Service de la géoinformation, DGEGM) Couvert 1: 1) Paucicrura rogata et Platystrophia amoena. Membre de Rosemont. Au SW de Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu. Photo: tirée de Globensky, 1981b, page 39 2) Formation de Solomon's Corner. Saint-Armand-Station. Photo: tirée de Globensky, 1981b, page 126 3) Faciès de Terrebonne, formation de Tétreauville. Rivière L'Assomption. Photo: Y. Globensky 4) Formation de Covey Hill. Coupe à l'extrémité NW du lac Gulf, à l'ouest de Covey Hill. Photo: tirée de Globensky, 1986, page 9 Couvert 4: 1) Formation d'Indian Point. Péninsule de Forillon. Photo: D. Brisebois 2) Coupe type de la Formation de Wallace Creek. Étang Streit, près de Philipsburg. Photo: tirée de Globensky, 1981b, page 101 3) Euomphalopsis sp.