History of Samoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomacy and the American Civil War: the Impact on Anglo- American Relations

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-8-2020 Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo- American relations Johnathan Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Seitz, Johnathan, "Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo-American relations" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 56. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The Impact on Anglo-American Relations Johnathan Bryant Seitz A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. David Dillard Dr. John Butt Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................iii Abstract............................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

Stevensoniana; an Anecdotal Life and Appreciation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ed. from the Writings of J.M. Barrie, S.R. Crocket

——; — ! 92 STEVENSONIANA VIII ISLAND DAYS TO TUSITALA IN VAILIMA^ Clearest voice in Britain's chorus, Tusitala Years ago, years four-and-twenty. Grey the cloudland drifted o'er us, When these ears first heard you talking, When these eyes first saw you smiling. Years of famine, years of plenty, Years of beckoning and beguiling. Years of yielding, shifting, baulking, ' When the good ship Clansman ' bore us Round the spits of Tobermory, Glens of Voulin like a vision. Crags of Knoidart, huge and hoary, We had laughed in light derision. Had they told us, told the daring Tusitala, What the years' pale hands were bearing, Years in stately dim division. II Now the skies are pure above you, Tusitala; Feather'd trees bow down to love you 1 This poem, addressed to Robert Louis Stevenson, reached him at Vailima three days before his death. It was the last piece of verse read by Stevenson, and it is the subject of the last letter he wrote on the last day of his life. The poem was read by Mr. Lloyd Osbourne at the funeral. It is here printed, by kind permission of the author, from Mr. Edmund Gosse's ' In Russet and Silver,' 1894, of which it was the dedication. After the Photo by] [./. Davis, Apia, Samoa STEVENSON AT VAILIMA [To face page i>'l ! ——— ! ISLAND DAYS 93 Perfum'd winds from shining waters Stir the sanguine-leav'd hibiscus That your kingdom's dusk-ey'd daughters Weave about their shining tresses ; Dew-fed guavas drop their viscous Honey at the sun's caresses, Where eternal summer blesses Your ethereal musky highlands ; Ah ! but does your heart remember, Tusitala, Westward in our Scotch September, Blue against the pale sun's ember, That low rim of faint long islands. -

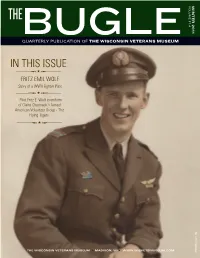

In This Issue

VOLUME 17:4 2011 WINTER IN THIS ISSUE FRITZ EMIL WOLF Story of a WWII Fighter Pilot Pilot Fritz E. Wolf in uniform of Claire Chennault’s famed American Volunteer Group - The Flying Tigers. THE WISCONSIN VETERANS MUSEUM MADISON, WI WWW.WISVETSMUSEUM.COM WVM Mss 2011.102 FROM THE DIRECTOR Wisconsin Veterans Museum. How soldier in the 7th Wisconsin. He may could it be otherwise? We are sur- have read about the Iron Brigade rounded by things that resonate in books, but the idea of advancing with stories of Wisconsin’s veterans. shoulder to shoulder in line of battle In this issue you will read stories under musket and cannon fire was about three men who, although sep- a relic of a far away past. Likewise, arated by time, embody commonly Hunt could never have imagined held traits that link them together Wolf’s airplane, let alone land- among a long line of veterans. We ing one on the deck of a ship. As a start with the account of the in- resident of Kenosha, Isermann may trepid naval combat flying ace Fritz have known veterans of Hunt’s Iron Wolf, a native of Madison by way of Brigade, but their ancient exploits Shawano, Wisconsin who flew with were long ago events separated by Claire Chennault’s Flying Tigers in more than fifty years from the Great China, and later with the US Navy. War. To a twentieth century man Wolf’s story is followed by the tragic engaged in WWI naval operations, account of an English immigrant, Gettysburg might as well have been John Hunt, who settled in Wiscon- Thermopylae. -

Stevensoniana; an Anecdotal Life and Appreciation of Robert Louis Stevenson, Ed. from the Writings of JM Barrie, SR Crocket

: R. L. S. AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES 225 XII R. L. S. AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES Few authors of note have seen so many and frank judg- ments of their work from the pens of their contemporaries as Stevenson saw. He was a ^persona grata ' with the whole world of letters, and some of his m,ost admiring critics were they of his own craft—poets, novelists, essayists. In the following pages the object in view has been to garner a sheaf of memories and criticisms written—before and after his death—for the most part by eminent contemporaries of the novelist, and interesting, apart from intrinsic worth, by reason of their writers. Mr. Henry James, in his ' Partial Portraits,' devotes a long and brilliant essay to Stevenson. Although written seven years prior to Stevenson's death, and thus before some of the most remarkable productions of his genius had appeared, there is but little in -i^^^ Mr. James's paper which would require modi- fication to-day. Himself the wielder of a literary style more elusive, more tricksy than Stevenson's, it is difficult to take single passages from his paper, the whole galaxy of thought and suggestion being so cleverly meshed about by the dainty frippery of his manner. Mr. James begins by regretting the 'extinction of the pleasant fashion of the literary portrait,' and while deciding that no individual can bring it back, he goes on to say It is sufficient to note, in passing, that if Mr. Stevenson had P 226 STEVENSONIANA presented himself in an age, or in a country, of portraiture, the painters would certainly each have had a turn at him. -

Top Things to Do in Apia" This Quaint Capital of Samoa Is Known for Its Old Capital Mulinu'u and the Primary City Cathedral

"Top Things To Do in Apia" This quaint capital of Samoa is known for its old capital Mulinu'u and the primary city cathedral. But primarily, its the azure waters, the golden sand beaches and the green cityscape that brings in visitors year in, year out. 创建: Cityseeker 10 位置已标记 Mount Vaea山 "Samoa's Natural Landmark" One of Samoa’s most famous sights is the emerald green peak of Mount Vaea, where the famed writer Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife Fanny are buried. Buried here in 1894, the renowned writer spent the last four years of his life enjoying Samoa’s natural splendor. The trail up to Stevenson’s grave, which sits in the by Teinesavaii shadow of Mount Vaea’s peak, is known as the “Road of Loving Hearts.” Visitors to the burial site will have roughly an hour long walk ahead of them, their eyes treated to beautiful vistas along the way. The surrounding forests are protected by the Stevenson Memorial Reserve and Mount Vaea Scenic Reserve Ordinance. +685 6 3500 (Tourist Information) Off Cross Island Road, Apia To-Sua海沟 "Aquamarine Paradise" Right in the middle of a forested sprawl is a gaping swimming hole, filled with gorgeous aquamarine water that simply demands diving into. This stunning attraction is located on the island of Upolu. Visitors must descend a ladder to reach the diving point, from where they can plunge into epic crystalline waters below. by Rickard Törnblad +685 4 1699 www.to- tosua.oceantrench@gmail. Main South Coast Road, suaoceantrench.com/ com Apia 罗伯特·路易斯·史蒂文森博物馆 "A Poetic Tour" Catch a glimpse into the life and work of Scottish poet Robert Louis Stevenson at this beautiful, well-preserved museum, where this legendary literary figure spent the last few years of his life. -

Marchofempire.Pdf

JIMMY SWAGGART BIBLE COLLEGE/SEMINARY LIBRARY ' . JIMMY SWAGGART BIBLE COLLEGE AND SEMINARY LIBRARY BATON ROUGE, LOUISIANA .. "' I l.J MARCH OF EMPIRE Af+td . .JV l cg s- Rg I '7 4 ~ MARCH OF EMPIRE The European Overseas Possessions on the Eve of the First World War By Lowell Ragatz, F .R.H.S. Professor of European History in The George Washington University Foreword by Alfred Martineau CASCADE COLLEGE LIBRARY H. L. LINDQUIST New York THE CANADIAN CHRISTMAS STAMP OF 1898, THE EPITOME OF MODERN IMPERIALISM. The phrase~ ~~we hold a vaster en1pire than has been," is excerpted from Jubilee Ode, by the Welsh poet, Sir Lewis Morris (1833 -1907). Copyright, 1948 By LOWELL RAGATZ PRJ NTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA To CauKo and PANCHO LIANG, Dear Friends of Long Ago FORE"\\TORD The period from the Fashoda Crisis to the outbreak of the great World War in 1914 has been generally neglected by specialists in European expansion. It is as though the several colonial empires had become static entities upon the close of the 19th century and that nothing of consequence had transpired in any of them in the decade and a half prior to the outbreak of that global struggle marking the end of an era in Modern Imperialism. Nothing is~ of course, farther fro~ the truth. I have, therefore, suggested to my former student and present colleague in the field of colonial studies, Professor Lowell Ragatz~ of The George Washington University in the United States, that he write a small volume filling this singular gap in the writings on modern empire building. -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph. -

Robert Louis Stevenson's Dentist: Unsung Hero

Wright State University CORE Scholar Annual Conference Presentations, Papers, and Posters Ohio Academy of Medical History 5-7-2011 Robert Louis Stevenson's Dentist: Unsung Hero Robert B. Stevenson The Ohio State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/oamh_presentations Part of the Medical Education Commons Repository Citation Stevenson, R. B. (2011). Robert Louis Stevenson's Dentist: Unsung Hero. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/oamh_presentations/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ohio Academy of Medical History at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Conference Presentations, Papers, and Posters by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dentist Unsung Hero Robert B. Stevenson, DDS, MS, MA RLS in Samoa 1893 Year before fatal stroke robert-louis-stevenson.org • http://www.robert-louis-stevenson.org/ • Links to all his published works, most biographies, all known photos • Links to seven RLS museums worldwide • His footsteps from cradle to grave • Links to periodicals like the RLS Club newsletter and Journal of Stevenson Studies JSS Volume 4, pages 43-51 Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson November 13, 1850 – December 4, 1894 • Was an only child • Mother called him Lewis • Nurse Cummy, Lew • Father, Smout (a small fish used for bait) • Friends & Cousin Bob, Louis (“Louie”) • At 21, changed to Robert Louis Stevenson • Wife & step-children, Luly • Wife’s ex-husband, That putrid windbag Robert Stevenson Common name • 1830 Ohio Census found eight people named Robert Stevenson Grandfather Robert Stevenson June 8, 1772 – July 7, 1850 Civil engineer, lighthouse builder & more Bell Rock Lighthouse, 1811 • 1st lighthouse built on tidal rock Bell Rock • Inchcape Rock, before the bell on a buoy An Engineering Wonder • Bell Rock Lighthouse 200 feet tall • Storm waves have gone over the top, and the light stayed burning. -

Mavae and Tofiga

Mavae and Tofiga Spatial Exposition of the Samoan Cosmogony and Architecture Albert L. Refiti A thesis submitted to� The Auckland University of Technology �In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art & Design� Faculty of Design & Creative Technologies 2014 Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i Attestation of Authorship ...................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ viii Abstract .................................................................................................................................... ix Preface ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Leai ni tusiga ata: There are to be no drawings ............................................................. 1 2. Tautuanaga: Rememberance and service ....................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6 Spacing .................................................................................................................................. -

Subsistence in Samoa: Influences of the Capitalist Global Economy on Conceptions of Wealth and Well-Being

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 Subsistence in Samoa: influences of the capitalist global economy on conceptions of wealth and well-being Tess Hosman SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, Growth and Development Commons, Pacific Islands Languages and Societies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Hosman, Tess, "Subsistence in Samoa: influences of the capitalist global economy on conceptions of wealth and well-being" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3045. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3045 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Subsistence in Samoa: influences of the capitalist global economy on conceptions of wealth and well-being Tess Hosman Advisor Mika Maiava Dr. Fetaomi Tapu-Qiliho S.I.T. Samoa, Spring 2019 Hosman 1 Abstract This paper studies Samoa’s position in the global economy as an informal agricultural economy. A country’s access to the global economy reflects a level of socio-economic development and political power. It is also reflective of the country’s history of globalization. This research uses an analysis of past and current forms of colonization that continue to influence cultural and ideological practices, specifically practices regarding food. -

Samoan Ghost Stories: John Kneubuhl and Oral History

SAMOAN GHOST STORIES John Kneubuhl and oral history1 [ReceiveD November 11th 2017; accepteD February 26th 2018 – DOI: 10.21463/shima.12.1.06] Otto Heim The University of Hong Kong <[email protected]> ABSTRACT: HaileD as "the spiritual father of Pacific IslanD theatre" (Balme, 2007: 194), John Kneubuhl is best known as a playwright anD a HollywooD scriptwriter. Less well known is that after his return to Samoa in 1968 he also devoteD much of his time to the stuDy anD teaching of Polynesian culture anD history. The sense of personal anD cultural loss, which his plays often dramatise in stories of spirit possession, also guiDeD his investment in oral history, in the form of extenDeD series of radio talks anD public lectures, as well as long life history interviews. BaseD on archival recordings of this oral history, this article consiDers Kneubuhl's sense of history anD how it informs his most autobiographical play, Think of a Garden (1992). KEYWORDS: John Kneubuhl; Samoan history; concept of the va; fale aitu - - - - - - - John Kneubuhl is best remembereD as a playwright, “the spiritual father of Pacific IslanD theatre,” as Christopher Balme has calleD him (2007: 194), a forerunner who calleD for “Pacific plays by Pacific playwrights” as early as 1947 (Kneubuhl, 1947a). Also well known is that he was a successful scriptwriter for famous HollywooD television shows such as Wild Wild West, The Fugitive, anD Hawaii Five-O. Less well-known, however, is that after he left HollywooD in 1968 anD returneD to Samoa, he devoteD much of his time to the stuDy anD teaching of Polynesian anD particularly Samoan history anD culture anD became a highly regardeD authority in this fielD. -

Robert Louis Stevenson

Published on Great Writers Inspire (http://writersinspire.org) Home > Robert Louis Stevenson Robert Louis Stevenson Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson (1850-1894) was born in Edinburgh on the 13 November 1850. His father and grandfather were both successful engineers who built many of the lighthouses that dotted the Scottish coast, whilst his mother came from a family of lawyers and church ministers. A sickly boy whose mother was also often unwell, Stevenson spent much of his childhood with the family nurse, Alison Cunningham. She told him many ghost stories and supernatural tales which seem to resonate throughout Stevenson's later fiction, reappearing in several of his short-stories, such as 'The Body Snatchers', 'The Merry Men' [1], and 'Thrawn Janet'. In 1867, Stevenson enrolled at Edinburgh University to study engineering. The choice of subject was influenced by Stevenson's father, who wished his son to continue the prestigious family tradition. Stevenson however had other ambitions, and even at this early stage, expressed a desire to write. He shortly changed courses and began to study law, but soon gave this up to concentrate on writing professionally, much to the displeasure of his father. [2] By alberto (Ana Quiroga) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Stevenson married Fanny Osborne in May 1880. The newly-married couple set off on honeymoon together, accompanied by Fanny's son, Lloyd Osborne, from her previous marriage. The three started their trip in San Francisco, traveling through the Napa Valley to eventually arrive at an abandoned gold mine on Mount St Helena. Stevenson would later write about this experience in his travel memoir The Silverado Squatters (1883).