Peckham Settlement: Bingo, Reminiscing and Nursery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vision for Social Housing

Building for our future A vision for social housing The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing Building for our future: a vision for social housing 2 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Contents Contents The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing For more information on the research that 2 Foreword informs this report, 4 Our commissioners see: Shelter.org.uk/ socialhousing 6 Executive summary Chapter 1 The housing crisis Chapter 2 How have we got here? Some names have been 16 The Grenfell Tower fire: p22 p46 changed to protect the the background to the commission identity of individuals Chapter 1 22 The housing crisis Chapter 2 46 How have we got here? Chapter 3 56 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 3 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 4 The consequences of the decline p56 p70 Chapter 4 70 The consequences of the decline Chapter 5 86 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 90 Reforming social renting Chapter 7 Chapter 5 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 Reforming social renting 102 Reforming private renting p86 p90 Chapter 8 112 Building more social housing Recommendations 138 Recommendations Chapter 7 Reforming private renting Chapter 8 Building more social housing Recommendations p102 p112 p138 4 Building for our future: a vision for social housing 5 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Foreword Foreword Foreword Reverend Dr Mike Long, Chair of the commission In January 2018, the housing and homelessness charity For social housing to work as it should, a broad political Shelter brought together sixteen commissioners from consensus is needed. -

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

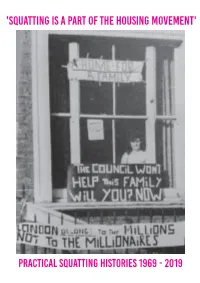

'Squatting Is a Part of the Housing Movement'

'Squatting Is A Part OF The HousinG Movement' PRACTICAL SQUATTING HISTORIES 1969 - 2019 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘...I learned how to crack window panes with a hammer muffled in a sock and then to undo the catch inside. Most houses were uninhabit- able, for they had already been dis- embowelled by the Council. The gas and electricity were disconnected, the toilets smashed...Finally we found a house near King’s Cross. It was a disused laundry, rather cramped and with a shopfront window...That night we changed the lock. Next day, we moved in. In the weeks that followed, the other derelict houses came to life as squatting spread. All the way up Caledonian Road corrugated iron was stripped from doors and windows; fresh paint appeared, and cats, flow- erpots, and bicycles; roughly printed posters offered housing advice and free pregnancy testing...’ Sidey Palenyendi and her daughters outside their new squatted home in June Guthrie, a character in the novel Finsbury Park, housed through the ‘Every Move You Make’, actions of Haringey Family Squatting Association, 1973 Alison Fell, 1984 Front Cover: 18th January 1969, Maggie O’Shannon & her two children squatted 7 Camelford Rd, Notting Hill. After 6 weeks she received a rent book! Maggie said ‘They might call me a troublemaker. Ok, if they do, I’m a trouble maker by fighting FOR the rights of the people...’ 'Squatting Is Part Of The Housing Movement' ‘Some want to continue living ‘normal lives,’ others to live ‘alternative’ lives, others to use squatting as a base for political action. -

Neighbourhoods in England Rated E for Green Space, Friends of The

Neighbourhoods in England rated E for Green Space, Friends of the Earth, September 2020 Neighbourhood_Name Local_authority Marsh Barn & Widewater Adur Wick & Toddington Arun Littlehampton West and River Arun Bognor Regis Central Arun Kirkby Central Ashfield Washford & Stanhope Ashford Becontree Heath Barking and Dagenham Becontree West Barking and Dagenham Barking Central Barking and Dagenham Goresbrook & Scrattons Farm Barking and Dagenham Creekmouth & Barking Riverside Barking and Dagenham Gascoigne Estate & Roding Riverside Barking and Dagenham Becontree North Barking and Dagenham New Barnet West Barnet Woodside Park Barnet Edgware Central Barnet North Finchley Barnet Colney Hatch Barnet Grahame Park Barnet East Finchley Barnet Colindale Barnet Hendon Central Barnet Golders Green North Barnet Brent Cross & Staples Corner Barnet Cudworth Village Barnsley Abbotsmead & Salthouse Barrow-in-Furness Barrow Central Barrow-in-Furness Basildon Central & Pipps Hill Basildon Laindon Central Basildon Eversley Basildon Barstable Basildon Popley Basingstoke and Deane Winklebury & Rooksdown Basingstoke and Deane Oldfield Park West Bath and North East Somerset Odd Down Bath and North East Somerset Harpur Bedford Castle & Kingsway Bedford Queens Park Bedford Kempston West & South Bedford South Thamesmead Bexley Belvedere & Lessness Heath Bexley Erith East Bexley Lesnes Abbey Bexley Slade Green & Crayford Marshes Bexley Lesney Farm & Colyers East Bexley Old Oscott Birmingham Perry Beeches East Birmingham Castle Vale Birmingham Birchfield East Birmingham -

2017 09 19 South Lambeth Estate

LB LAMBETH EQUALITY IMPACT ASSESSMENT August 2018 SOUTH LAMBETH ESTATE REGENERATION PROGRAMME www.ottawaystrategic.co.uk $es1hhqdb.docx 1 5-Dec-1810-Aug-18 Equality Impact Assessment Date August 2018 Sign-off path for EIA Head of Equalities (email [email protected]) Director (this must be a director not responsible for the service/policy subject to EIA) Strategic Director or Chief Exec Directorate Management Team (Children, Health and Adults, Corporate Resources, Neighbourhoods and Growth) Procurement Board Corporate EIA Panel Cabinet Title of Project, business area, Lambeth Housing Regeneration policy/strategy Programme Author Ottaway Strategic Management Ltd Job title, directorate Contact email and telephone Strategic Director Sponsor Publishing results EIA publishing date EIA review date Assessment sign off (name/job title): $es1hhqdb.docx 2 5-Dec-1810-Aug-18 LB Lambeth Equality Impact Assessment South Lambeth Estate Regeneration Programme Independently Reported by Ottaway Strategic Management ltd August 2018 Contents EIA Main Report 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 4 2 Introduction and context ....................................................................................... 12 3 Summary of equalities evidence held by LB Lambeth ................................................ 17 4 Primary Research: Summary of Household EIA Survey Findings 2017 ........................ 22 5 Equality Impact Assessment .................................................................................. -

Why We Have 'Mixed Communities' Policies and Some Difficulties In

Notes for Haringey Housing and Regeneration Scrutiny Panel Dr Jane Lewis London Metropolitan University April 3rd 2017 Dr Jane Lewis • Dr Jane Lewis is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Social Policy at London Metropolitan University. She has worked previously as a lecturer in urban regeneration and in geography as well as in urban regeneration and economic development posts in local government in London. Jane has wide experience teaching at under-graduate and post-graduate levels with specific expertise in urban inequalities; globalisation and global inequalities; housing and urban regeneration policy and is course leader of the professional doctorate programme in working lives and of masters’ courses in urban regeneration and sustainable cities dating back to 2005.Jane has a research background in cities and in urban inequalities, urban regeneration policy and economic and labour market conditions and change. aims • 1. Invited following presentation Haringey Housing Forum on concerns relating to council estate regeneration schemes in London in name of mixed communities polices • 2. Senior Lecturer Social Policy at LMU (attached note) • 3. Terms of reference of Scrutiny Panel focus on 1and 2 – relating to rehousing of council tenants in HDV redevelopments and to 7 – equalities implications Haringey Development Vehicle (HDV) and Northumberland Park • ‘development projects’ proposed for the first phase of the HDV include Northumberland Park Regeneration Area – includes 4 estates, Northumberland Park estate largest • Northumberland Park -

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017 Part of the London Plan evidence base COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Contents Chapter Page 0 Executive summary 1 to 7 1 Introduction 8 to 11 2 Large site assessment – methodology 12 to 52 3 Identifying large sites & the site assessment process 53 to 58 4 Results: large sites – phases one to five, 2017 to 2041 59 to 82 5 Results: large sites – phases two and three, 2019 to 2028 83 to 115 6 Small sites 116 to 145 7 Non self-contained accommodation 146 to 158 8 Crossrail 2 growth scenario 159 to 165 9 Conclusion 166 to 186 10 Appendix A – additional large site capacity information 187 to 197 11 Appendix B – additional housing stock and small sites 198 to 202 information 12 Appendix C - Mayoral development corporation capacity 203 to 205 assigned to boroughs 13 Planning approvals sites 206 to 231 14 Allocations sites 232 to 253 Executive summary 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Executive summary 0.1 The SHLAA shows that London has capacity for 649,350 homes during the 10 year period covered by the London Plan housing targets (from 2019/20 to 2028/29). This equates to an average annualised capacity of 64,935 homes a year. -

Who Is Council Housing For?

‘We thought it was Buckingham Palace’ ‘Homes for Heroes’ Cottage Estates Dover House Estate, Putney, LCC (1919) Cottage Estates Alfred and Ada Salter Wilson Grove Estate, Bermondsey Metropolitan Borough Council (1924) Tenements White City Estate, LCC (1938) Mixed Development Somerford Grove, Hackney Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Neighbourhood Units The Lansbury Estate, Poplar, LCC (1951) Post-War Flats Spa Green Estate, Finsbury Metropolitan Borough Council (1949) Berthold Lubetkin Post-War Flats Churchill Gardens Estate, City of Westminster (1951) Architectural Wars Alton East, Roehampton, LCC (1951) Alton West, Roehampton, LCC (1953) Multi-Storey Housing Dawson’s Heights, Southwark Borough Council (1972) Kate Macintosh The Small Estate Chinbrook Estate, Lewisham, LCC (1965) Low-Rise, High Density Lambeth Borough Council Central Hill (1974) Cressingham Gardens (1978) Camden Borough Council Low-Rise, High Density Branch Hill Estate (1978) Alexandra Road Estate (1979) Whittington Estate (1981) Goldsmith Street, Norwich City Council (2018) Passivhaus Mixed Communities ‘The key to successful communities is a good mix of people: tenants, leaseholders and freeholders. The Pepys Estate was a monolithic concentration of public housing and it makes sense to break that up a bit and bring in a different mix of incomes and people with spending power.’ Pat Hayes, LB Lewisham, Director of Regeneration You have castrated communities. You have colonies of low income people, living in houses provided by the local authorities, and you have the higher income groups living in their own colonies. This segregation of the different income groups is a wholly evil thing, from a civilised point of view… We should try to introduce what was always the lovely feature of English and Welsh villages, where the doctor, the grocer, the butcher and the farm labourer all lived in the same street – the living tapestry of a mixed community. -

Annex E2 Visit Reports.Pdf

Annex E2 Final Report Working Group 1 – Engineers WG1: Report on visit to the Ledbury Estate, Peckham, Southwark November 30th 2018. The Ledbury Estate is in Peckham and includes four 14-storey Large Panel System (LPS) tower blocks. The estate belongs to Southwark Council. The buildings were built for the GLC between 1968 and 1970. The dates of construction as listed as Bromyard (1968), Sarnsfield (1969), Skenfrith (1969) and Peterchurch House (1970). The WG1 group visited Peterchurch House on November 30th 2018. The WG1 group was met by Tony Hunter, Head of Engineering, and, Stuart Davis, Director of Asset Management and Mike Tyrrell, Director of the Ledbury Estate. The Ledbury website https://www.southwark.gov.uk/housing/safety-in-the-home/fire-safety-on-the- ledbury-estate?chapter=2 includes the latest Fire Risk Assessments, the Arup Structural Reports and various Residents Voice documents. This allowed us a good understanding of the site situation before the visit. In addition, Tony Hunter sent us copies of various standard regulatory reports. Southwark use Rowanwood Apex Asset Management System to manage their regulatory and ppm work. Following the Structural Surveys carried out by Arup in November 2017 which advised that the tower construction was not adequate to withstand a gas explosion, all piped gas was removed from the Ledbury Estate and a distributed heat system installed with Heat Interface Units (HIU) in each flat. Currently fed by an external boiler system. A tour of Peterchurch House was made including a visit to an empty flat where the Arup investigation points could be seen. -

Territorial Stigmatisation and Poor Housing at a London `Sink Estate'

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 20–33 DOI: 10.17645/si.v8i1.2395 Article Territorial Stigmatisation and Poor Housing at a London ‘Sink Estate’ Paul Watt Department of Geography, Birkbeck, University of London, London, WC1E 7HX, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 4 August 2019 | Accepted: 9 December 2019 | Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract This article offers a critical assessment of Loic Wacquant’s influential advanced marginality framework with reference to research undertaken on a London public/social housing estate. Following Wacquant, it has become the orthodoxy that one of the major vectors of advanced marginality is territorial stigmatisation and that this particularly affects social housing es- tates, for example via mass media deployment of the ‘sink estate’ label in the UK. This article is based upon a multi-method case study of the Aylesbury estate in south London—an archetypal stigmatised ‘sink estate.’ The article brings together three aspects of residents’ experiences of the Aylesbury estate: territorial stigmatisation and dissolution of place, both of which Wacquant focuses on, and housing conditions which he neglects. The article acknowledges the deprivation and various social problems the Aylesbury residents have faced. It argues, however, that rather than internalising the extensive and intensive media-fuelled territorial stigmatisation of their ‘notorious’ estate, as Wacquant’s analysis implies, residents have largely disregarded, rejected, or actively resisted the notion that they are living in an ‘estate from hell,’ while their sense of place belonging has not dissolved. By contrast, poor housing—in the form of heating breakdowns, leaks, infes- tation, inadequate repairs and maintenance—caused major distress and frustration and was a more important facet of their everyday lives than territorial stigmatisation. -

Download (591Kb)

This is the author’s version of the article, first published in Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal, Volume 8 / Number 2 / Winter, 2014-15, pp. 133- 144 (12). https://www.henrystewartpublications.com/jurr Understanding and measuring social sustainability Email [email protected] Abstract Social sustainability is a new strand of discourse on sustainable development. It has developed over a number of years in response to the dominance of environmental concerns and technological solutions in urban development and the lack of progress in tackling social issues in cities such as inequality, displacement, liveability and the increasing need for affordable housing. Even though the Sustainable Communities policy agenda was introduced in the UK a decade ago, the social dimensions of sustainability have been largely overlooked in debates, policy and practice around sustainable urbanism. However, this is beginning to change. A combination of financial austerity, public sector budget cuts, rising housing need, and public & political concern about the social outcomes of regeneration, are focusing attention on the relationship between urban development, quality of life and opportunities. There is a growing interest in understanding and measuring the social outcomes of regeneration and urban development in the UK and internationally. A small, but growing, movement of architects, planners, developers, housing associations and local authorities advocating a more ‘social’ approach to planning, constructing and managing cities. This is part of an international interest in social sustainability, a concept that is increasingly being used by governments, public agencies, policy makers, NGOs and corporations to frame decisions about urban development, regeneration and housing, as part of a burgeoning policy discourse on the sustainability and resilience of cities. -

Estate Regeneration

ESTATE REGENERATION sourcebook Estate Regeneration Sourcebook Content: Gavin McLaughlin © February 2015 Urban Design London All rights reserved [email protected] www.urbandesignlondon.com Cover image: Colville Phase 2 Karakusevic Carson Architects 2 Preface As we all struggle to meet the scale and complexity of London’s housing challenges, it is heartening to see the huge number of successful estate regeneration projects that are underway in the capital. From Kidbrooke to Woodberry Down, Clapham Park to Graeme Park, South Acton to West Hendon, there are estates being transformed all across London. All are complicated, but most are moving ahead with pace, delivering more homes of all tenures and types, to a better quality, and are offering improved accommodation, amenities and environments for existing residents and newcomers alike. The key to success in projects as complex as estate regeneration lies in the quality of the partnerships and project teams that deliver them and, crucially, in the leadership offered by local boroughs. That’s why I welcome this new resource from UDL as a useful tool to help those involved with such projects to see what’s happening elsewhere and to use the networks that London offers to exchange best practice. Learning from the successes – and mistakes – of others is usually the key to getting things right. London is a fascinating laboratory of case studies and this new sourcebook is a welcome reference point for those already working on estate regeneration projects or those who may be considering doing so in the future. David Lunts Executive Director of Housing and Land at the GLA Introduction There is a really positive feeling around estate regeneration in London at the moment.