Salt-Smart Americas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sodium and Kidney Disease

Sodium and Kidney Disease What is sodium? Sodium is a mineral found in food and all Did You Know? types of salt. We need a very small amount 1 teaspoon (5 mL) of of sodium for body water balance. However, table salt has 2325 mg of most people eat more sodium than they sodium. need. Where does sodium come from? How much sodium should I eat each day? • Processed foods: salt and other sodium additives are found in most packaged You should limit sodium to 2300 mg or less and prepared foods at the grocery store. each day. Aim for less than 600 mg for a Most of the sodium we eat comes from meal and less than 250 mg for a snack. processed foods. • The salt shaker: added in cooking and at Why do I need to limit sodium? the table. • Natural content: small amounts of sodium With kidney disease your kidneys do not is found naturally in most foods. balance sodium and water well. If you eat too much sodium you may have: How can I eat less sodium? • High blood pressure • Thirst • Do not add salt to your food. • Puffy hands, face and feet • Do not add salt during cooking. • Too much fluid around your heart and • Use fresh or frozen (without salt) meat, lungs, making it hard to breathe chicken, fish, seafood, eggs, vegetables • Cramps during hemodialysis and fruits. These are naturally low in sodium. By eating less sodium, you can help control • Make your meals with fresh ingredients. these problems. • Avoid high sodium foods such as: − Ham, bacon, salami and other deli Some medications used to protect the meats kidneys and lower blood pressure work − Pickles, olives, relish better when your diet is lower in sodium. -

Structural and Functional Characterization of the N-Terminal Acetyltransferase Natc

Structural and functional characterization of the N-terminal acetyltransferase NatC Inaugural-Dissertation to obtain the academic degree Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) submitted to the Department of Biology, Chemistry, Pharmacy of Freie Universität Berlin by Stephan Grunwald Berlin October 01, 2019 Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von April 2014 bis Oktober 2019 am Max-Delbrück-Centrum für Molekulare Medizin unter der Anleitung von PROF. DR. OLIVER DAUMKE angefertigt. Erster Gutachter: PROF. DR. OLIVER DAUMKE Zweite Gutachterin: PROF. DR. ANNETTE SCHÜRMANN Disputation am 26. November 2019 iii iv Erklärung Ich versichere, dass ich die von mir vorgelegte Dissertation selbstständig angefertigt, die benutzten Quellen und Hilfsmittel vollständig angegeben und die Stellen der Arbeit – einschließlich Tabellen, Karten und Abbildungen – die anderen Werken im Wortlaut oder dem Sinn nach entnommen sind, in jedem Einzelfall als Entlehnung kenntlich gemacht habe; und dass diese Dissertation keiner anderen Fakultät oder Universität zur Prüfung vorgelegen hat. Berlin, 9. November 2020 Stephan Grunwald v vi Acknowledgement I would like to thank Prof. Oliver Daumke for giving me the opportunity to do the research for this project in his laboratory and for the supervision of this thesis. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Annette Schürmann from the German Institute of Human Nutrition (DifE) in Potsdam-Rehbruecke for being my second supervisor. From the Daumke laboratory I would like to especially thank Dr. Manuel Hessenberger, Dr. Stephen Marino and Dr. Tobias Bock-Bierbaum, who gave me helpful advice. I also like to thank the rest of the lab members for helpful discussions. I deeply thank my wife Theresa Grunwald, who always had some helpful suggestions and kept me alive while writing this thesis. -

Effect of Sodium Nitrite, Sodium Erythorbate and Organic Acid Salts on Germination and Outgrowth of Clostridium Perfringens Spores in Ham During Abusive Cooling

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology Food Science and Technology Department Fall 9-19-2011 Effect of Sodium Nitrite, Sodium Erythorbate and Organic Acid Salts on Germination and Outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens Spores in Ham during Abusive Cooling Mauricio A. Redondo University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/foodscidiss Part of the Food Chemistry Commons, Food Microbiology Commons, and the Food Processing Commons Redondo, Mauricio A., "Effect of Sodium Nitrite, Sodium Erythorbate and Organic Acid Salts on Germination and Outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens Spores in Ham during Abusive Cooling" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology. 18. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/foodscidiss/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Food Science and Technology Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. EFFECT OF SODIUM NITRITE, SODIUM ERYTHORBATE AND ORGANIC ACID SALTS ON GERMINATION AND OUTGROWTH OF CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS SPORES IN HAM DURING ABUSIVE COOLING By Mauricio Redondo-Solano A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Food Science and Technology Under the supervision of Professor Harshavardhan Thippareddi Lincoln, Nebraska September, 2011 EFFECT OF SODIUM NITRITE, SODIUM ERYTHORBATE AND ORGANIC ACID SALTS ON GERMINATION AND OUTGROWTH OF CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS SPORES IN HAM DURING ABUSIVE COOLING Mauricio Redondo-Solano, M. -

Sensory Characteristics of Salt Substitute Containing L-Arginine

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2006 Sensory characteristics of salt substitute containing L-arginine Pamarin Waimaleongora-Ek Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Waimaleongora-Ek, Pamarin, "Sensory characteristics of salt substitute containing L-arginine" (2006). LSU Master's Theses. 762. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/762 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SENSORY CHARACTERISTICS OF SALT SUBSTITUTE CONTAINING L-ARGININE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In The Department of Food Science by Pamarin Waimaleongora-Ek B.S., Food Science and Technology, Thammasat University, 2002 December 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my immense gratitude towards my major professor and advisor, Dr. Witoon Prinyawiwatkul, who has always been there for me with his help, guidance, patience and understanding throughout the years. I have enjoyed being his student and learned so much from him. Besides my advisor, I would like to thank Dr. Zhimin Xu who served as a co-chair, and Dr. Beilei Ge, who served as a committee for everything that they have done for me and their help with my research. -

Title Low Sodium Salt of Botanic Origin

(12) STANDARD PATENT (11) Application No. AU 2004318169 B2 (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE (54) Title Low sodium salt of botanic origin (51) International Patent Classification(s) A23L 1/237 (2006.01) C01D 3/04 (2006.01) (21) Application No: 2004318169 (22) Date of Filing: 2004.11.09 (87) WIPO No: W005/097681 (30) Priority Data (31) Number (32) Date (33) Country 10/819,001 2004.04.06 US (43) Publication Date: 2005.10.20 (44) Accepted Journal Date: 2010.12.09 (71) Applicant(s) Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (72) Inventor(s) Bhatt, Ajoy Muralidharbhai;Eswaran, Karuppanan;Patolia, Jinalal Shambhubhai;Reddy, Alamuru Venkata Rami;Shah, Rajul Ashvinbhai;Barot, Bhargav Kaushikbhai;Mehta, Aditya Shantibhai;Gandhi, Mahesh Ramniklal;Mody, Kalpana Haresh;Reddy, Muppala Parandhami;Ghosh, Pushpito Kumar (74) Agent / Attorney Cullens Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys, Level 32 239 George Street, Brisbane, QLD, 4000 (12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization 11111|11| 1 111 |1 11111111 1111| 1111111|111 1111111 ||111 International Bureau 1111111 111111 111111111111111 1111 ii1111li iili (43) International Publication Date (10) International Publication Number 20 October 2005 (20.10.2005) PCT WO 2005/097681 Al (51) International Patent Classification7 : C01D 3/04, Marine Chemicals Research Institute, Bhavnagar, Gujarat A23L 1/237 364 002 (IN). BHATT, Ajoy, Muralidharbhai [IN/IN]; Central Salt and Marine Chemicals Research Institute, (21) International Application Number: Bhavnagar, Gujarat 364 002 (IN). REDDY, Alamuru, PCT/IB2004/003678 Venkata, Rami [IN/IN]; Central Salt and Marine Chemi cals Research Institute, Bhavnagar, Gujarat 364 002 (IN). (22) International Filing Date:9(74) Agents: BHOLA, Ravi et al.; K & S Partners, 84-C, C6 November 2004 (09.11.2004) Lane, Off Central Avenue, Sainik Farms, New Delhi 110 062 (IN). -

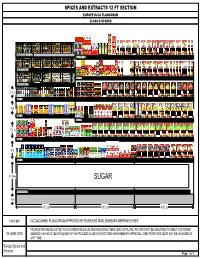

SPICES and EXTRACTS 12 FT SECTION EUROPE Deca PLANOGRAM CLASS D STORES

SPICES AND EXTRACTS 12 FT SECTION EUROPE DeCA PLANOGRAM CLASS D STORES Gravity Feed: 01 TOP Shelf: 09 TOP Mcc ormi ck Cum Gravity Feed: 02 in 521 000 Shelf: 10 Gravity Feed: 03 5.12 in Shelf: 04 Mccormick Mrs Dash Mrs Dash Molly Perf Pnch Fiesta Tomato McButter Garlic & 6 in Lime Basil n Sprinkles Bell Pepper 60502160 Garlic Original Seas 5210002686 Shelf: 05 K2/CHG Shelf: 11 7.24 in Shelf: 06 8 in Shelf: 07 13.24 in SUGAR Shelf: 08 BASE 5 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in Left-right HQ DeCA/MBU PLANOGRAM APPROVED BY BUSINESS MGR, BARBARA MERRIWEATHER. FACINGS MAY BE ADJUSTED TO ACCOMODATE LOCAL AND REGIONAL ITEMS (END OF FLOW). FACINGS MAY BE ADJUSTED TO MEET CUSTOMER 15 JUNE 2015 DEMAND-CAO MUST BE INVOLVED IN THE PROCESS ALONG WITH STORE MANAGEMENT APPROVAL. ITEM POSITIONS MUST NOT BE CHANGED AT ANY TIME. Europe Spices and Extracts Page: 1 of 6 SPICES AND EXTRACTS 12 FT SECTION EUROPE DeCA PLANOGRAM CLASS D STORES Mccor Mccormick Mccormi Old Bay mick Vanilla Asst.F ck Seafood ood Red Mccor Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick Mccor Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick 52100071 Food Chili Powder Cinnamon Seasoning Mccormick Colors mick Basil Whole Bay Celery Salt mick Chili Freeze Stick Cinnamon Ground Mc Mccormi Mccormi Mc Mc Mccormi McCorm Mc Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Bakers Color 7032800523 03 Vanilla 521000 Groun Leaves Leaves 521000050 Whol Powder Dried Cinnamon Sugar Cloves cor ck ck cor cor ck ick cor ck ck ck ck ck ck ck 5210007 5210007108 Ground Extract Vanilla 7107 d 521000069 521000069 8 -

Textural, Microstructural and Sensory Properties of Reduced Sodium Frankfurter Sausages Containing Mechanically Deboned Poultry Meat and Blends of Chloride Salts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Food Research International 66 (2014) 29–35 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food Research International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodres Textural, microstructural and sensory properties of reduced sodium frankfurter sausages containing mechanically deboned poultry meat and blends of chloride salts C.N. Horita a,⁎,V.C.Messiasa,M.A.Morganob,F.M.Hayakawaa,M.A.R.Pollonioa a Department of Food Technology, Faculty of Food Engineering, State University of Campinas, UNICAMP, Cidade Universitária Zeferino Vaz, CP 6121, 13083-862 Campinas, SP, Brazil b Food Technology Institute, ITAL, Brazil Avenue, 2880, 13070-178 Campinas, SP, Brazil article info abstract Article history: The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of salt substitutes on the textural, microstructural and Received 31 March 2014 sensory properties in low-cost frankfurter sausages produced using mechanically deboned poultry meat Accepted 1 September 2014 (MDPM) as a potential strategy to reduce sodium in this meat product. In nine treatments, blends of calcium, Available online 6 September 2014 sodium and potassium chloride were used to substitute 25% or 50% of the NaCl in sausages (at the same ionic strength and molar basis equivalent to 2% NaCl). When NaCl was partially replaced by 50% CaCl2 (F6), the batter Keywords: fi Salt reduction presented the highest total liquid released, and the corresponding nal product showed increased hardness Emulsion stability when compared to the control formulation (100% NaCl, C1). Its respective microstructural analysis revealed Calcium chloride numerous pores arranged in a noncompacted matrix, which could be explained by the lowest emulsion stability Mechanically deboned poultry meat reported for samples with 50% CaCl2 and 50% NaCl. -

ABSTRACT DIXON, ELIZABETH MARIE. Whey Permeate

ABSTRACT DIXON, ELIZABETH MARIE. Whey Permeate, Delactosed Permeate, and Delactosed Whey as Ingredients to Lower Sodium Content of Cream Based Soups. (Under the direction of Jonathan C. Allen) The use of whey permeates as salt substitutes can help to decrease sodium and chloride intake, increase potassium, calcium and magnesium intakes and decrease hypertension risk. Five different whey permeates from 5 different manufacturers were analyzed with ICP for mineral content (Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn). Two permeates are powder and three are liquid. Lactose and protein content were also analyzed by Lactose/D-Glucose UV kit from Roche and BCA protein assay, respectively. Chloride and phosphate were measured spectrophotometrically. Basic tastes and aromas were quantified by a trained sensory panel. Based on the highest “salty taste” identified by the trained sensory panel, one liquid and one solid permeate were further investigated as sodium substitutes. The sodium content of the guideline solutions for comparing salty taste of the permeates were used to calculate the equivalent concentrations of salt and permeate for salty taste in aqueous solution. Two soup formulations were used to test the use of permeate as a salt substitute; one retorted, canned, condensed cream soup base, and one fresh cream soup base. Each formulation of soup was tested on a separate day by 75 consumer panelists who averaged between 20 and 30 years of age. Four samples were given each day 0%, 50%, 100% of the standard salt content in condensed soup, and permeate at a content calculated to be equal in salty taste to the standard salt content. -

March 26, 2010 Carole Davis Corexecutive Secretary of The

March 26, 2010 Carole Davis CoRExecutive Secretary of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Center of Nutrition Policy and Promotion U.S. Department of Agriculture 3101 Park Center Drive, Room 1034 Alexandria, VA 22303 RE: 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans Dear Ms. Davis and the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: The American Meat Institute (AMI) is the nation's oldest and largest meat packing and processing industry trade association. AMI members slaughter and process more than 90 percent of the nation's beef, pork, lamb, veal, and a majority of the turkey produced in the United States. On behalf of AMI and its member companies, we appreciate the opportunity to comment on the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (or the Guidelines). AMI has and will continue to support the use of sound science as the foundation for nutritional public policy. AMI would like to commend the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (the Committee) for its structured approach in compiling the data, modifying proposed nutritional targets, and working with the food industry in a partnered approach to improve consumer public health. The health of our customers is the driving force in the production of meat and poultry products, not only with respect to improving the safety of meat and poultry products, but also in offering diverse nutritional products to consumers so they can make an educated decision in choosing the food that best fits their personal lifestyle and family needs. The following comments address specific concerns that require further clarification and/or additional consideration prior to finalizing the Guidelines. Sodium Plays an Important Role in Meat Production and Safety Salt or sodium chloride plays a critical role in the production of meat products -- whether used by large commercial processors, local butchers, or even within the consumer’s home -- to improve the flavor, texture, and safety of those products. -

Sodium Reduction Through Salt Substitute Mixtures, Visual Cues

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-31-2019 Sodium Reduction Through Salt Substitute Mixtures, Visual Cues, and Salt Level Statements, and Its Effects on Consumer Perception: A Case of Barbecue Sauce Jose Ramon Alonso Marenco Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Other Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Alonso Marenco, Jose Ramon, "Sodium Reduction Through Salt Substitute Mixtures, Visual Cues, and Salt Level Statements, and Its Effects on Consumer Perception: A Case of Barbecue Sauce" (2019). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4962. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4962 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SODIUM REDUCTION THROUGH SALT SUBSTITUTE MIXTURES, VISUAL CUES, AND SALT LEVEL STATEMENTS, AND ITS EFFECTS ON CONSUMER PERCEPTION: A CASE OF BARBECUE SAUCE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Nutrition and Food Sciences by Jose Ramon Alonso Marenco B.S., Escuela Agricola Panamericana, El Zamorano, 2009 August 2019 i Acknowledgments I owe an endless and heartfelt gratitude to the people who enabled me this opportunity. Thank you Dr. William Richardson and all the wonderful people who embody the AgCenter. -

Artisanal Salt Production in Aveiro/Portugal - an Ecofriendly Process Carolina M Rodrigues1*, Ana Bio1, Francisco Amat2 and Natividade Vieira1,3

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC Rodrigues et al. Saline Systems 2011, 7:3 http://www.salinesystems.org/content/7/1/3 SALINE SYSTEMS REVIEW Open Access Artisanal salt production in Aveiro/Portugal - an ecofriendly process Carolina M Rodrigues1*, Ana Bio1, Francisco Amat2 and Natividade Vieira1,3 Abstract Solar salinas are man-made systems exploited for the extraction of salt, by solar and wind evaporation of seawater. Salt production achieved by traditional methods is associated with landscapes and environmental and patrimonial values generated throughout history. Since the mid-twentieth century, this activity has been facing a marked decline in Portugal, with most salinas either abandoned or subjected to destruction, making it necessary to find a strategy to reverse this trend. It is, however, possible to generate revenue from salinas at several levels, not merely in terms of good quality salt production, but also by obtaining other products that can be commercialized, or by exploring their potential for tourism, and as research facilities, among others. Furthermore, with an adequate management, biodiversity can be restored to abandoned salinas, which constitute important feeding and breeding grounds for resident and migratory aquatic birds, many of which are protected by European Community Directives. The aims of this manuscript are to present a brief overview on the current state of sea salt exploitation in Portugal and to stress the importance of recovering these salinas for the conservation of this particular environment, for the regional economy, the scientific community and the general public. The Aveiro salina complex is presented in detail, to exemplify salina structure and functioning, as well as current problems and potential solutions for artisanal salinas. -

Facts, Issues, and Controversies in Salt Reduction for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Francesco P

ARTICLE Facts, Issues, and Controversies in Salt Reduction for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Francesco P. Cappuccio, DSc, FRCP, Simon Capewell, DSc, FFPH Current salt consumption in human societies is now much greater than needed for survival. Furthermore, high salt intake substantially increases blood pressure (BP) in both animals and humans. Conversely, a reduction in salt intake causes a dose- dependent reduction in BP in men and women of all ages and ethnic groups and in patients already on medication. The risk of strokes and heart attacks rises with increasing BP but can be decreased by antihypertensive drugs. However, the majority of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events occur in the numerous individuals with ‘‘normal’’ BP levels below the ‘‘clinically hypertensive’’ level which might trigger drug therapy. Nonpharmacological prevention is therefore the only option to reduce the majority of such events. Reductions in population salt intake consistently reduce the number of subsequent CVD events (with additional benefits for the heart, kidneys, stomach, and skeleton). Indeed, this is one of the most important public health measures for reducing the global CVD burden. The most successful policies involve comprehensive which ideally include population monitoring, health education, and reformulation to reduce the salt content concealed in processed foods (which represent over 75% of daily salt intake). Such population-wide salt reduction policies are generally powerful, rapid, equitable, and cost saving. Inevitably, the food and beverage industries, which profit from marketing salt, will try to oppose such policies. However, public health has triumphed in those countries prepared to consider the necessary levers: regulation, legislation, and even taxation.