Potassium Chloride As a Salt Substitute in Bread

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials and Method

Jalil, Abbe Maleyki Mhd (2016) Development of functional bread with beta glucan and black tea and effects on appetite regulation, glucose and insulin responses in healthy volunteers. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7956/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Development of Functional Bread with Beta Glucan and Black Tea and Effects on Appetite Regulation, Glucose and Insulin Responses in Healthy Volunteers Abbe Maleyki Mhd Jalil BSc, MSc A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy To The College of Medicine, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow July 2016 From research conducted at the School of Medicine, Human Nutrition University of Glasgow Glasgow Royal Infirmary, 10-16 Alexandra Parade, G31 2ER Glasgow, Scotland © A.M.M Jalil 2016 Author's declaration I declare that the original work presented in this thesis is the work of the author Abbe Maleyki Mhd Jalil. I have been responsible for the organisation, recruitment, sample collection, laboratory work, statistical analysis and data processing of the whole research, unless otherwise stated. -

Sodium and Kidney Disease

Sodium and Kidney Disease What is sodium? Sodium is a mineral found in food and all Did You Know? types of salt. We need a very small amount 1 teaspoon (5 mL) of of sodium for body water balance. However, table salt has 2325 mg of most people eat more sodium than they sodium. need. Where does sodium come from? How much sodium should I eat each day? • Processed foods: salt and other sodium additives are found in most packaged You should limit sodium to 2300 mg or less and prepared foods at the grocery store. each day. Aim for less than 600 mg for a Most of the sodium we eat comes from meal and less than 250 mg for a snack. processed foods. • The salt shaker: added in cooking and at Why do I need to limit sodium? the table. • Natural content: small amounts of sodium With kidney disease your kidneys do not is found naturally in most foods. balance sodium and water well. If you eat too much sodium you may have: How can I eat less sodium? • High blood pressure • Thirst • Do not add salt to your food. • Puffy hands, face and feet • Do not add salt during cooking. • Too much fluid around your heart and • Use fresh or frozen (without salt) meat, lungs, making it hard to breathe chicken, fish, seafood, eggs, vegetables • Cramps during hemodialysis and fruits. These are naturally low in sodium. By eating less sodium, you can help control • Make your meals with fresh ingredients. these problems. • Avoid high sodium foods such as: − Ham, bacon, salami and other deli Some medications used to protect the meats kidneys and lower blood pressure work − Pickles, olives, relish better when your diet is lower in sodium. -

18º Curso De Mestrado Em Saúde Pública 2015-2017 Saturated Fat

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Científico do Instituto Nacional de Saúde 18º Curso de Mestrado em Saúde Pública 2015-2017 Saturated fat, sodium and sugar in selected food items: A comparison across six European countries Jennifer Marie Tretter Ferreira September, 2017 i “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” Benjamin Franklin ii iii 18º Curso de Mestrado em Saúde Pública 2015-2017 Saturated fat, sodium and sugar in selected food items: A comparison across six European countries Dissertation submitted to meet the requisites required to obtain a Master's Degree in Public Health, carried out under the scientific guidance of Dr. Carla Nunes and Dr. Maria Graça Dias. September, 2017 iv v Special thanks to the availability and guidance of Dr. Carla Nunes and Dr. Maria Graça Dias. For patiently answering questions, explaining processes and always directing me on the correct path. You both have been amazing mentors. A special thanks as well to Dr. Isabel Andrade. You have been a wealth of knowledge and relief on the technical side of writing. This thesis is dedicated to: Edgar for always supporting my goals and life ambitions André and Daniel, my two continual motivations to pursue the best in life Manuela and Agnelo for their availability and kindness to help pick up wherever I could not Mom and Dad for the constant moral and monetary support throughout my life and this process vi vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................vi -

A Study of Salt Content of Different Bread Types Marketed in Amman, Jordan

Journal of Agricultural Science; Vol. 8, No. 4; 2016 ISSN 1916-9752 E-ISSN 1916-9760 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education A Study of Salt Content of Different Bread Types Marketed in Amman, Jordan Fatema M. Abu Hussain1 & Hamed R. Takruri1 1 Department of Nutrition and Food Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan Correspondence: Hamed R. Takruri, Department of Nutrition and Food Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 17, 2016 Accepted: March 1, 2016 Online Published: March 15, 2016 doi:10.5539/jas.v8n4p169 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jas.v8n4p169 Abstract Noncommunicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of premature death in the 21st century. Dietary factors such as high salt intake constitute the main risk factors. Bread is considered as one of the most important sources of dietary salt. The objectives of this study were to determine the sodium content of the main types of bread that are marketed in Amman, and to evaluate the bakers’ adherence to the Jordanian specifications. Sixty eight bread samples of seven types of bread were collected from 13 different bakeries distributed in Amman. Bread samples were dried, ashed and the sodium content was directly determined by using flame photometry method. The average salt content of the analyzed bread samples was 1.19±0.21 g salt/100 g of fresh bread, ranging between 0.42 g/100 g for white Arabic bread and 2.06±0.19 for shrak bread. -

Structural and Functional Characterization of the N-Terminal Acetyltransferase Natc

Structural and functional characterization of the N-terminal acetyltransferase NatC Inaugural-Dissertation to obtain the academic degree Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) submitted to the Department of Biology, Chemistry, Pharmacy of Freie Universität Berlin by Stephan Grunwald Berlin October 01, 2019 Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von April 2014 bis Oktober 2019 am Max-Delbrück-Centrum für Molekulare Medizin unter der Anleitung von PROF. DR. OLIVER DAUMKE angefertigt. Erster Gutachter: PROF. DR. OLIVER DAUMKE Zweite Gutachterin: PROF. DR. ANNETTE SCHÜRMANN Disputation am 26. November 2019 iii iv Erklärung Ich versichere, dass ich die von mir vorgelegte Dissertation selbstständig angefertigt, die benutzten Quellen und Hilfsmittel vollständig angegeben und die Stellen der Arbeit – einschließlich Tabellen, Karten und Abbildungen – die anderen Werken im Wortlaut oder dem Sinn nach entnommen sind, in jedem Einzelfall als Entlehnung kenntlich gemacht habe; und dass diese Dissertation keiner anderen Fakultät oder Universität zur Prüfung vorgelegen hat. Berlin, 9. November 2020 Stephan Grunwald v vi Acknowledgement I would like to thank Prof. Oliver Daumke for giving me the opportunity to do the research for this project in his laboratory and for the supervision of this thesis. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Annette Schürmann from the German Institute of Human Nutrition (DifE) in Potsdam-Rehbruecke for being my second supervisor. From the Daumke laboratory I would like to especially thank Dr. Manuel Hessenberger, Dr. Stephen Marino and Dr. Tobias Bock-Bierbaum, who gave me helpful advice. I also like to thank the rest of the lab members for helpful discussions. I deeply thank my wife Theresa Grunwald, who always had some helpful suggestions and kept me alive while writing this thesis. -

Effect of Sodium Nitrite, Sodium Erythorbate and Organic Acid Salts on Germination and Outgrowth of Clostridium Perfringens Spores in Ham During Abusive Cooling

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology Food Science and Technology Department Fall 9-19-2011 Effect of Sodium Nitrite, Sodium Erythorbate and Organic Acid Salts on Germination and Outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens Spores in Ham during Abusive Cooling Mauricio A. Redondo University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/foodscidiss Part of the Food Chemistry Commons, Food Microbiology Commons, and the Food Processing Commons Redondo, Mauricio A., "Effect of Sodium Nitrite, Sodium Erythorbate and Organic Acid Salts on Germination and Outgrowth of Clostridium perfringens Spores in Ham during Abusive Cooling" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology. 18. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/foodscidiss/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Food Science and Technology Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. EFFECT OF SODIUM NITRITE, SODIUM ERYTHORBATE AND ORGANIC ACID SALTS ON GERMINATION AND OUTGROWTH OF CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS SPORES IN HAM DURING ABUSIVE COOLING By Mauricio Redondo-Solano A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Food Science and Technology Under the supervision of Professor Harshavardhan Thippareddi Lincoln, Nebraska September, 2011 EFFECT OF SODIUM NITRITE, SODIUM ERYTHORBATE AND ORGANIC ACID SALTS ON GERMINATION AND OUTGROWTH OF CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS SPORES IN HAM DURING ABUSIVE COOLING Mauricio Redondo-Solano, M. -

Sensory Characteristics of Salt Substitute Containing L-Arginine

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2006 Sensory characteristics of salt substitute containing L-arginine Pamarin Waimaleongora-Ek Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Waimaleongora-Ek, Pamarin, "Sensory characteristics of salt substitute containing L-arginine" (2006). LSU Master's Theses. 762. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/762 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SENSORY CHARACTERISTICS OF SALT SUBSTITUTE CONTAINING L-ARGININE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In The Department of Food Science by Pamarin Waimaleongora-Ek B.S., Food Science and Technology, Thammasat University, 2002 December 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my immense gratitude towards my major professor and advisor, Dr. Witoon Prinyawiwatkul, who has always been there for me with his help, guidance, patience and understanding throughout the years. I have enjoyed being his student and learned so much from him. Besides my advisor, I would like to thank Dr. Zhimin Xu who served as a co-chair, and Dr. Beilei Ge, who served as a committee for everything that they have done for me and their help with my research. -

Monika Michalak-Majewska1*, Siemowit Muszyński2, Bartosz

ACTAACTA UNIVERSITATISUNIVERSITATIS CIBINIENSISCIBINIENSIS 10.2478/aucft-2020-0009 SeriesSeries E:E: FoodFood technology technology COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SELECTED PHYSICOCHEMICAL AND TEXTURAL PROPERTIES OF BREAD SUBSTITUTES – Research paper – Monika MICHALAK-MAJEWSKA*1, Siemowit MUSZYŃSKI**, Bartosz SOŁOWIEJ***, Wojciech RADZKI*, Waldemar GUSTAW*, Katarzyna SKRZYPCZAK*, Piotr STANIKOWSKI* *Department of Plant Food Technology and Gastronomy, Faculty of Food Sciences and Biotechnology, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Skromna 8, 20-704 Lublin, Poland **Department of Biophysics, Faculty of Environmental Biology, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Akademicka 13, 20-950 Lublin, Poland ***Department of Milk Technology and Hydrocolloids, Faculty of Food Sciences and Biotechnology, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Skromna 8, 20-704 Lublin, Poland Abstract: In the present study, the physicochemical, textural and sensorial properties of crackerbread (made from rye, maize and wheat flour) and rice waffles, the most popular on the Polish market bread substitutes, were determined. It was shown that values of several mechanical properties of rice waffles, including ultimate fracture force, strain and stress differed significantly from that of crackerbread. Texture profile analysis showed that the highest hardness and springiness was exhibited by rice waffles with sesame seeds and wheat-rye, respectively. The concentration of salt was the lowest in rice bread with sunflower. The most acceptable was the rice bread with sea salt (8.26 in a 9-point scale) and overall consumer acceptance of crispbreads was highly correlated with sensory attribute of saltiness. Keywords: bread substitute, crispbread, rice waffles, texture, sensory INTRODUCTION tional and health value to some consumers (Jarosz, In recent years, the consumption of traditional bread 2015). -

Title Low Sodium Salt of Botanic Origin

(12) STANDARD PATENT (11) Application No. AU 2004318169 B2 (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE (54) Title Low sodium salt of botanic origin (51) International Patent Classification(s) A23L 1/237 (2006.01) C01D 3/04 (2006.01) (21) Application No: 2004318169 (22) Date of Filing: 2004.11.09 (87) WIPO No: W005/097681 (30) Priority Data (31) Number (32) Date (33) Country 10/819,001 2004.04.06 US (43) Publication Date: 2005.10.20 (44) Accepted Journal Date: 2010.12.09 (71) Applicant(s) Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (72) Inventor(s) Bhatt, Ajoy Muralidharbhai;Eswaran, Karuppanan;Patolia, Jinalal Shambhubhai;Reddy, Alamuru Venkata Rami;Shah, Rajul Ashvinbhai;Barot, Bhargav Kaushikbhai;Mehta, Aditya Shantibhai;Gandhi, Mahesh Ramniklal;Mody, Kalpana Haresh;Reddy, Muppala Parandhami;Ghosh, Pushpito Kumar (74) Agent / Attorney Cullens Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys, Level 32 239 George Street, Brisbane, QLD, 4000 (12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization 11111|11| 1 111 |1 11111111 1111| 1111111|111 1111111 ||111 International Bureau 1111111 111111 111111111111111 1111 ii1111li iili (43) International Publication Date (10) International Publication Number 20 October 2005 (20.10.2005) PCT WO 2005/097681 Al (51) International Patent Classification7 : C01D 3/04, Marine Chemicals Research Institute, Bhavnagar, Gujarat A23L 1/237 364 002 (IN). BHATT, Ajoy, Muralidharbhai [IN/IN]; Central Salt and Marine Chemicals Research Institute, (21) International Application Number: Bhavnagar, Gujarat 364 002 (IN). REDDY, Alamuru, PCT/IB2004/003678 Venkata, Rami [IN/IN]; Central Salt and Marine Chemi cals Research Institute, Bhavnagar, Gujarat 364 002 (IN). (22) International Filing Date:9(74) Agents: BHOLA, Ravi et al.; K & S Partners, 84-C, C6 November 2004 (09.11.2004) Lane, Off Central Avenue, Sainik Farms, New Delhi 110 062 (IN). -

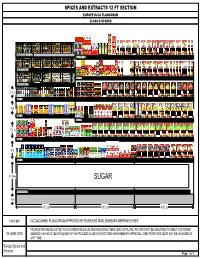

SPICES and EXTRACTS 12 FT SECTION EUROPE Deca PLANOGRAM CLASS D STORES

SPICES AND EXTRACTS 12 FT SECTION EUROPE DeCA PLANOGRAM CLASS D STORES Gravity Feed: 01 TOP Shelf: 09 TOP Mcc ormi ck Cum Gravity Feed: 02 in 521 000 Shelf: 10 Gravity Feed: 03 5.12 in Shelf: 04 Mccormick Mrs Dash Mrs Dash Molly Perf Pnch Fiesta Tomato McButter Garlic & 6 in Lime Basil n Sprinkles Bell Pepper 60502160 Garlic Original Seas 5210002686 Shelf: 05 K2/CHG Shelf: 11 7.24 in Shelf: 06 8 in Shelf: 07 13.24 in SUGAR Shelf: 08 BASE 5 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in 4 ft 1 in Left-right HQ DeCA/MBU PLANOGRAM APPROVED BY BUSINESS MGR, BARBARA MERRIWEATHER. FACINGS MAY BE ADJUSTED TO ACCOMODATE LOCAL AND REGIONAL ITEMS (END OF FLOW). FACINGS MAY BE ADJUSTED TO MEET CUSTOMER 15 JUNE 2015 DEMAND-CAO MUST BE INVOLVED IN THE PROCESS ALONG WITH STORE MANAGEMENT APPROVAL. ITEM POSITIONS MUST NOT BE CHANGED AT ANY TIME. Europe Spices and Extracts Page: 1 of 6 SPICES AND EXTRACTS 12 FT SECTION EUROPE DeCA PLANOGRAM CLASS D STORES Mccor Mccormick Mccormi Old Bay mick Vanilla Asst.F ck Seafood ood Red Mccor Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick Mccor Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick Mccormick 52100071 Food Chili Powder Cinnamon Seasoning Mccormick Colors mick Basil Whole Bay Celery Salt mick Chili Freeze Stick Cinnamon Ground Mc Mccormi Mccormi Mc Mc Mccormi McCorm Mc Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Mccormi Bakers Color 7032800523 03 Vanilla 521000 Groun Leaves Leaves 521000050 Whol Powder Dried Cinnamon Sugar Cloves cor ck ck cor cor ck ick cor ck ck ck ck ck ck ck 5210007 5210007108 Ground Extract Vanilla 7107 d 521000069 521000069 8 -

Textural, Microstructural and Sensory Properties of Reduced Sodium Frankfurter Sausages Containing Mechanically Deboned Poultry Meat and Blends of Chloride Salts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Food Research International 66 (2014) 29–35 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food Research International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodres Textural, microstructural and sensory properties of reduced sodium frankfurter sausages containing mechanically deboned poultry meat and blends of chloride salts C.N. Horita a,⁎,V.C.Messiasa,M.A.Morganob,F.M.Hayakawaa,M.A.R.Pollonioa a Department of Food Technology, Faculty of Food Engineering, State University of Campinas, UNICAMP, Cidade Universitária Zeferino Vaz, CP 6121, 13083-862 Campinas, SP, Brazil b Food Technology Institute, ITAL, Brazil Avenue, 2880, 13070-178 Campinas, SP, Brazil article info abstract Article history: The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of salt substitutes on the textural, microstructural and Received 31 March 2014 sensory properties in low-cost frankfurter sausages produced using mechanically deboned poultry meat Accepted 1 September 2014 (MDPM) as a potential strategy to reduce sodium in this meat product. In nine treatments, blends of calcium, Available online 6 September 2014 sodium and potassium chloride were used to substitute 25% or 50% of the NaCl in sausages (at the same ionic strength and molar basis equivalent to 2% NaCl). When NaCl was partially replaced by 50% CaCl2 (F6), the batter Keywords: fi Salt reduction presented the highest total liquid released, and the corresponding nal product showed increased hardness Emulsion stability when compared to the control formulation (100% NaCl, C1). Its respective microstructural analysis revealed Calcium chloride numerous pores arranged in a noncompacted matrix, which could be explained by the lowest emulsion stability Mechanically deboned poultry meat reported for samples with 50% CaCl2 and 50% NaCl. -

ABSTRACT DIXON, ELIZABETH MARIE. Whey Permeate

ABSTRACT DIXON, ELIZABETH MARIE. Whey Permeate, Delactosed Permeate, and Delactosed Whey as Ingredients to Lower Sodium Content of Cream Based Soups. (Under the direction of Jonathan C. Allen) The use of whey permeates as salt substitutes can help to decrease sodium and chloride intake, increase potassium, calcium and magnesium intakes and decrease hypertension risk. Five different whey permeates from 5 different manufacturers were analyzed with ICP for mineral content (Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn). Two permeates are powder and three are liquid. Lactose and protein content were also analyzed by Lactose/D-Glucose UV kit from Roche and BCA protein assay, respectively. Chloride and phosphate were measured spectrophotometrically. Basic tastes and aromas were quantified by a trained sensory panel. Based on the highest “salty taste” identified by the trained sensory panel, one liquid and one solid permeate were further investigated as sodium substitutes. The sodium content of the guideline solutions for comparing salty taste of the permeates were used to calculate the equivalent concentrations of salt and permeate for salty taste in aqueous solution. Two soup formulations were used to test the use of permeate as a salt substitute; one retorted, canned, condensed cream soup base, and one fresh cream soup base. Each formulation of soup was tested on a separate day by 75 consumer panelists who averaged between 20 and 30 years of age. Four samples were given each day 0%, 50%, 100% of the standard salt content in condensed soup, and permeate at a content calculated to be equal in salty taste to the standard salt content.