Five N‰Siâha Temples in Andhra Pradesh and Their Function As a Religious Collective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11. Brahmotsavam

Our Sincere thanks to: 1. 'kaimkarya ratnam' Anbil Sri. Ramaswamy Swami, Editor of SrIRangaSrI e-magazine for his special report on the Brahmotsava Celebrations at Pomona, New York. 2. Sri. Murali Desikachari for compiling the source document 3. Sri.Lakshminarasimhan Sridhar, Sri.Malolan Cadambi, Sri. Murali BhaTTar of www.srirangapankajam.com. sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org www.ranganatha.org and Nedumtheru Sri.Mukund Srinivasan for contribution of images. 4. Smt. Jayashree Muralidharan for assembling the e-book. C O N T E N T S Introduction 1 Brahmotsava Ceremonies 5 Pre-Brahmotsavam 7 Ghanta Sevai 22 Bheri Taadanam 26 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Slokams used in Bheri Taadanam 31 Brahmotsavam at Pomona New York 73 Day 1 75 Day 2 80 Day 3 82 Final Day 84 In Conclusion 95 A special report by Sri. Anbil Ramaswamy 97 Just returned from Vaikuntham 99 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SrI ranganAtha with ubhaya nAcchiyArs during Brahmotsavam Pomona Temple, New York ïI> b INTRODUCTION Dear Sri RanganAyaki SamEtha Sri Ranganatha BhakthAs : The First BrahmOthsavam celebrations at Sri Ranganatha Temple have been sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org successfully concluded with the anugraham of Lord Ranganatha and the AchAaryAs. The details of each day's program is available at: http://www.Ranganatha.org A huge band of volunteers provided support for the various Kaimkaryams and including the Vaidhika events of the individual days from DhvajArOhaNam to DhvajAvarOhaNam. The daily alankArams, PuRappAdus, Live Naadhaswara Kaccheris, cultural events, Anna dhAnams, BhEri Taadanams et al during this BrahmOthsavam were a delight to enjoy. -

Tamilnadu.Pdf

TAKING TAMIL NADU AHEAD TAMIL NADU Andhra Pradesh Karnataka TAMIL NADU Kerala The coastal State of Tamil Nadu has seen rapid progress in road infrastructure development since 2014. The length of National Highways in the State has reached 7,482.87 km in 2018. Over 1,284.78 km of National Highways have been awarded in just four years at a cost of over Rs. 20,729.28 Cr. Benchmark projects such as the 115 km Madurai Ramanathapuram Expressway worth Rs. 1,134.35 Cr, are being built with investments to transform the State’s economy in coming years. “When a network of good roads is created, the economy of the country also picks up pace. Roads are veins and arteries of the nation, which help to transform the pace of development and ensure that prosperity reaches the farthest corners of our nation.” NARENDRA MODI Prime Minister “In the past four years, we have expanded the length of Indian National Highways network to 1,26,350 km. The highway sector in the country has seen a 20% growth between 2014 and 2018. Tourist destinations have come closer. Border, tribal and backward areas are being connected seamlessly. Multimodal integration through road, rail and port connectivity is creating socio economic growth and new opportunities for the people. In the coming years, we have planned projects with investments worth over Rs 6 lakh crore, to further expand the world’s second largest road network.” NITIN GADKARI Union Minister, Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, Shipping and Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Fast tracking National Highway development in Tamil Nadu NH + IN PRINCIPLE NH LENGTH UPTO YEAR 2018 7,482.87 km NH LENGTH UPTO YEAR 2014 5,006 km Adding new National Highways in Tamil Nadu 2,476.87 143.15 km km Yr 2014 - 2018 Yr 2010 - 2014 New NH New NH & In principle NH length 6 Cost of Road Projects awarded in Tamil Nadu Yr 2010 - 2014 Yr 2014 - 2018 Total Cost Total Cost Rs. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14 GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2018 [Price : Rs. 4.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 30] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JULY 25, 2018 Aadi 9, Vilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2049 Part VI—Section 3(a) Notifi cations issued by cost recoverable institutions of State and Central Governments. NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. CONTENTS Pages. JUDICIAL NOTIFICATIONS Insolvency Petitions .. .. .. .. .. .. 76-86 [ 75 ] DTP—VI-3(a)—30 76 TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE [Part VI—Sec. 3(a) NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. JUDICIAL NOTIFICATIONS INSOLVENCY PETITIONS IN THE COURT OF THE SUBORDINATE JUDGE OF BHAVANI (I. P. No. 1/2014) (è.â‡. 383/2018) No. VI-3(a)/65/2018. Nagarajan, Son of Pattappagounder, 65/307-C, Main Road, P. Mettupalayam, P. Mettupalayam Village, Bhavani Taluk, Erode District.—Petitioner/Creditor. Versus M.A. Govindasamy, Son of Andavagounder, 47/297A, Main Road, P. Mettupalayam Village, Bhavani Taluk, Erode District and 60 others—Respondents/Debtors. Notice is hereby given under Section 19(2) of Provincial Insolvency Act that the Petitioner/Debtors have applied to this Court praying to adjudge the petitioner as an Insolvent and that, the said petition stand by posted to 16-8-2018. Sub Court, Bhavani, ââ¡.¡. ïï£èô†²I£èô†²I, 20th July 2018. ꣘¹ cFðF. (I. P. No. 4/2014) (è.â‡. 383/2018) No. VI-3(a)/66/2018. Murugesan, Son of Perumal, 1/57, Kathiriyankadu, Poonachai Village, Anthiyur Taluk Erode District.—Petitioner/Creditor. Versus Ulaganathan, Son of Semmalai, Kathiriyankadu, Poonachi Village, Anthiyur Taluk, Erode District and 13 others— Respondents/Debtors. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

The Ancient Mesopotamian Place Name “Meluḫḫa”

THE ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN PLACE NAME “meluḫḫa” Stephan Hillyer Levitt INTRODUCTION The location of the Ancient Mesopotamian place name “Meluḫḫa” has proved to be difficult to determine. Most modern scholars assume it to be the area we associate with Indus Valley Civilization, now including the so-called Kulli culture of mountainous southern Baluchistan. As far as a possible place at which Meluḫḫa might have begun with an approach from the west, Sutkagen-dor in the Dasht valley is probably as good a place as any to suggest (Possehl 1996: 136–138; for map see 134, fig. 1). Leemans argued that Meluḫḫa was an area beyond Magan, and was to be identified with the Sind and coastal regions of Western India, including probably Gujarat. Magan he identified first with southeast Arabia (Oman), but later with both the Arabian and Persian sides of the Gulf of Oman, thus including the southeast coast of Iran, the area now known as Makran (1960a: 9, 162, 164; 1960b: 29; 1968: 219, 224, 226). Hansman identifies Meluḫḫa, on the basis of references to products of Meluḫḫa being brought down from the mountains, as eastern Baluchistan in what is today Pakistan. There are no mountains in the Indus plain that in its southern extent is Sind. Eastern Baluchistan, on the other hand, is marked throughout its southern and central parts by trellised ridges that run parallel to the western edge of the Indus plain (1973: 559–560; see map [=fig. 1] facing 554). Thapar argues that it is unlikely that a single name would refer to the entire area of a civilization as varied and widespread as Indus Valley Civilization. -

The Science Behind Sandhya Vandanam

|| 1 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 Sri Vaidya Veeraraghavan – Nacchiyar Thirukkolam - Thiruevvul 2 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 �ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || Sri Nrisimha Priya ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ AN AU T H O R I S E D PU B L I C A T I O N OF SR I AH O B I L A M A T H A M H. H. 45th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham H.H. 46th Jiyar of Sri Ahobila Matham Founder Sri Nrisimhapriya (E) H.H. Sri Lakshminrisimha H.H. Srivan Sathakopa Divya Paduka Sevaka Srivan Sathakopa Sri Ranganatha Yatindra Mahadesikan Sri Narayana Yatindra Mahadesikan Ahobile Garudasaila madhye The English edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya not only krpavasat kalpita sannidhanam / brings to its readers the wisdom of Vaishnavite Lakshmya samalingita vama bhagam tenets every month, but also serves as a link LakshmiNrsimham Saranam prapadye // between Sri Matham and its disciples. We confer Narayana yatindrasya krpaya'ngilaraginam / our benediction upon Sri Nrisimhapriya (English) Sukhabodhaya tattvanam patrikeyam prakasyate // for achieving a spectacular increase in readership SriNrsimhapriya hyesha pratigeham sada vaset / and for its readers to acquire spiritual wisdom Pathithranam ca lokanam karotu Nrharirhitam // and enlightenment. It would give us pleasure to see all devotees patronize this spiritual journal by The English Monthly Edition of Sri Nrisimhapriya is becoming subscribers. being published for the benefit of those who are better placed to understand the Vedantic truths through the medium of English. May this magazine have a glorious growth and shine in the homes of the countless devotees of Lord Sri Lakshmi Nrisimha! May the Lord shower His benign blessings on all those who read it! 3 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 4 Sri Nrisimha Priya (Volume 8 – Issue 7) July 2020 ी:|| ||�ीमते ल�मीनृिस륍हपर��णे नमः || CONTENTS Sri Nrisimha Priya Owner: Panchanga Sangraham 6 H.H. -

In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a Guide to the Temples, Beliefs and People of Tamil Nadu

* In the Kingdom of Nataraja, a guide to the temples, beliefs and people of Tamil Nadu The South India Saiva Siddhantha Works Publishing Society, Tinnevelly, Ltd, Madras, 1993. I.S.B.N.: 0-9661496-2-9 Copyright © 1993 Chantal Boulanger. All rights reserved. This book is in shareware. You may read it or print it for your personal use if you pay the contribution. This document may not be included in any for-profit compilation or bundled with any other for-profit package, except with prior written consent from the author, Chantal Boulanger. This document may be distributed freely on on-line services and by users groups, except where noted above, provided it is distributed unmodified. Except for what is specified above, no part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system - except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper - without permission in writing from the author. It may not be sold for profit or included with other software, products, publications, or services which are sold for profit without the permission of the author. You expressly acknowledge and agree that use of this document is at your exclusive risk. It is provided “AS IS” and without any warranty of any kind, expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. If you wish to include this book on a CD-ROM as part of a freeware/shareware collection, Web browser or book, I ask that you send me a complimentary copy of the product to my address. -

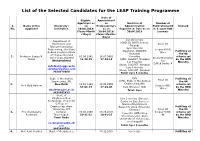

List of the Selected Candidates for the LEAP Training Programme

List of the Selected Candidates for the LEAP Training Programme Date of Eligible Appointment Age/58yrs as as Duration of Number of S. Name of the University / on Professor/8yrs Administrative Publications/30 Remark No. Applicant Institution 30.04.2019/ as on Experience/ 3yrs as on in Scopus-UGC (Years-Month 30.04.2019/ 30.04.2019 Journals s-Days) (Years-Months- Days) 1yr 10 months Department of (HOD, Dr. BATU, Lonere, Electronics and Total: 76 Raigad) Telecommunication 2yrs 8months Engineering, Shri Guru Scopus+UGC: (Registrar, SGGSIET, Fulfilling all Gobind Singhji Institute 30++ Nanded) the 04 of Engineering and 1. Professor Sanjay N. 01.06.1962 16.07.2001 8 months criteria set Technology, Nanded Books/Monograp Talbar 56-10-29 17-09-14 (HOD, SGGSIET, Nanded) by the HRD (Maharashtra) hs/ 1yr 7months Ministry Edited Books: 8 (Dean, SGGSIET, Nanded) [email protected] 1yrs 8 months [email protected] (Dean, SGGSIET, Nanded) 9850978050 Total: 8yrs 5 months Dept. of Mechanical 3yrs Fulfilling all Total: 95 Engineering, JMI, (HOD, Dept. of Mechanical the 04 2. New Delhi 11.02.1962 25.01.2002 Engineering, JMI) criteria set Prof. Abid Haleem Scopus-UGC: 57-02-19 17-03-05 5yrs (Director, IQA) by the HRD 30++ [email protected] Total: 8yrs Ministry 9818501633 Dept. of Pharmaceutical 5yrs 3 months (Director, Technology, University Centre for Excellence in College of NanobioTranslational Engineering, Anna Research, Anna University, Fulfilling all University, BIT Chennai) Total: 96 the 04 3. Prof. Kandasamy Campus, 08.05.1968 05.03.2005 Scopus+UGC: criteria set 5 months (Officiating Ruckmani Tiruchirapalli, 50-11-22 14-01-25 96 by the HRD Vice-Chancellor, Anna Tamil Nadu Ministry University of Technology, Tiruchirapalli) [email protected] u.in Total: 5yrs 8 months 9842484568 4. -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

Dr Anupama.Pdf

NJESR/July 2021/ Vol-2/Issue-7 E-ISSN-2582-5836 DOI - 10.53571/NJESR.2021.2.7.81-91 WOMEN AND SAMSKRIT LITERATURE DR. ANUPAMA B ASSISTANT PROFESSOR (VYAKARNA SHASTRA) KARNATAKA SAMSKRIT UNIVERSITY BENGALURU-560018 THE FIVE FEMALE SOULS OF " MAHABHARATA" The Mahabharata which has The epics which talks about tradition, culture, laws more than it talks about the human life and the characteristics of male and female which most relevant to this modern period. In Indian literature tradition the Ramayana and the Mahabharata authors talks not only about male characters they designed each and every Female characters with most Beautiful feminine characters which talk about their importance and dutiful nature and they are all well in decision takers and live their lives according to their decisions. They are the most powerful and strong and also reason for the whole Mahabharata which Occur. The five women in particular who's decision makes the whole Mahabharata to happen are The GANGA, SATYAVATI, AMBA, KUNTI and DRUPADI. GANGA: When king shantanu saw Ganga he totally fell for her and said "You must certainly become my wife, whoever you may be." Thus said the great King Santanu to the goddess Ganga who stood before him in human form, intoxicating his senses with her superhuman loveliness 81 www.njesr.com The king earnestly offered for her love his kingdom, his wealth, his all, his very life. Ganga replied: "O king, I shall become your wife. But on certain conditions that neither you nor anyone else should ever ask me who I am, or whence I come. -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www.