Sustainability Coffee Certification in India Perceptions and Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economics of Sustainable Coffee Production in Los Santos, Costa Rica

Economics of Sustainable Coffee Production in Los Santos, Costa Rica Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in International Development Studies at Wageningen University and Research Centre (WUR), The Netherlands By Thom van Wesel 1 2 ‘Economics of Sustainable Coffee Production in Los Santos, Costa Rica’ Course Code: DEC 80433 Author: Thom van Wesel Registration Number: 880617-941-060 Supervisors: Fernando Saenz CINPE, Costa Rica Rob Schipper Wageningen University and Research Centre (WUR) Development Economics | Wageningen University & Research Centre | August 2012 3 Acknowledgement The period working on this thesis represented both a challenging and an invaluable experience. From the moment I started my thesis I have acquired remarkable and new experiences with regards to studying and living abroad, familiarizing oneself with a new culture, language and above all people. For I am very grateful to the persons who have enabled and supported me throughout this thesis. Without them, bringing my thesis to a good end would have been far more difficult and challenging. First of all I would like to thank the household that were willing to participate in my research. I have been amazed often by their hospitality, kindness and openness of families. The families and persons I have encountered have always been willing to receive my, make time and help me with any questions. This would have been very hard to reach without the help of the cooperative ‘Cooperative de Caficultores de Llano Bonito' (CoopeLlanoBonito) whose employees were very helpful in establishing contact with producers. In addition, I would like to thank my supervisors: Rob Schipper, Kees Burger and Fernando Saenz. -

Coffee Production Costs and Farm Profitability: Strategic Literature Review

A Specialty Coffee Association Research Report Coffee Production Costs and Farm Profitability: Strategic Literature Review Dr Christophe Montagnon, RD2 Vision October 2017 Coffee Production Costs and Farm Profitability | Specialty Coffee Association Contents: 1)! Introduction 2)! Methodology: Document selection 2.1) Reviewing method 3)! Document comparison: Raw data collection 3.1) Variable and fixed costs 3.2) Family labor and net income 3.3) Distinguishing between averaged farms and different farm types 3.4) Focus on the Echeverria and Montoya document 3.5) Yield, profitability and production costs across Colombian regions in 2012 3.6) Correlating yield, profitability and production costs 3.7) Agronomic factors impacting yield, profitability and production costs 4)! Conclusions: Meta-analysis of different studies 4.1) Valuing the cost of production and profitability across different documents 4.2) Relationship between profitability, cost per hectare, cost per kg and yield 4.3) Main conclusions of the meta-analysis 4.4) Causes of household food insecurity 4.5) Limitations and recommendations of this literature review 5)! Next steps: Taking a strategic approach 6)! Annexes 7)! Glossary of terms List of tables Table 1: Grid analysis of reviewed documents Table 2: Description of the different reviewed documents according to the grid anlysis Table 3: Description of different coffee farm types (clusters) in Uganda Table 4: Yield, profitability and coffee costs in different regions of Colombia Table 5: Correlations between yield, profitability -

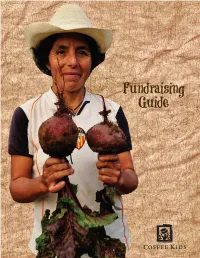

2012-Fundraising-Guide.Pdf

Introduction Coffee Kids was founded in 1988 as a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping coffee- farming families improve the quality of their lives and livelihoods. Our work is not related to the production or marketing of coffee, but rather to creating sustainable alternatives to coffee that will allow farmers and their families to reduce their reliance on this crop, while subsequently increasing economic independence. Coffee Kids only works with coffee-farming communities. Our partner organizations pro- vide hands-on training and technical skills to implement community improvements. Proj- ects generally fall within the categories of health care, economic diversification, education, capacity building and food security. Economics of Coffee Coffee is one of the most-traded commodities. Its prices are volatile and subject to a boom- bust pattern. Coffee prices are determined by speculative buying and selling. While prices during boom years are high, they are deceptive. The price paid to farmers has steadily dropped for generations. According to the World Bank, after inflation, coffee farmers earn less today than their ancestors did 100 years ago. When coffee prices drop, farmers do the only thing they know how to do: grow more cof- fee—and prices drop even further. Fair trade and other premiums have helped establish better prices for small farmers, provided roasters and vendors pay a more equitable price for coffee. If coffee farmers are to liberate themselves from the cycle of poverty, they must wean them- selves from over-dependency on the coffee harvest. Coffee Kids believes by helping coffee- farming families create additional sources of income and community infrastructure, they will be able to better care for themselves and their families. -

The Value of Time and Skill Acquisition in the Long Run: Evidence from Coffee Booms and Busts

The Value of Time and Skill Acquisition in the Long Run: Evidence from Coffee Booms and Busts Bladimir Carrillo ∗ October 23, 2018 Abstract This paper examines the long-run impacts of local income shocks on completed human capital. I exploit geographic variation in coffee cultivation patterns in Colom- bia and real-world coffee prices at the time cohorts were of school-going age in a differences-in-differences framework. Using five decades of data, I show that cohorts who faced sharp rises in the return to coffee-related work when they were of school- going age have lower educational attainment and are in lower-paid occupations. These findings suggest that transitory changes in the opportunity cost of schooling can cause permanent changes in human capital investments and not just a mere delay. JEL codes: J24; O12; O13. Keywords: coffee price shocks; transitory income shocks; human capital accumulation. ∗Correspondence: Department of Rural Economics, Universidade Federal de Vi¸cosa, AV Ph Rolfs, Vi¸cosa,BR 36570-000; email: [email protected]. I thank David Atkin, Raj Chetty, Rafael Corbi, Eduardo Correia, Sergio Firpo, Luis Galvis, Naercio Menezes, Renata Narita, Mathew Notowidigdo, Phillips Oreopoulos, Breno Sampaio, Gustavo Sampaio, Marcelo Santos, Jesse Shapiro, Ian Trotter, Paul Vaz, and seminar participants at various conferences and seminars for helpful comments and suggestions. I am especially grateful to Grant Miller and Piedad Urdinola for kindly sharing their data on coffee cultivation. All errors are my own. 1 Introduction How aggregate income shocks affect human capital is a question of central importance to both policymakers and economists. -

Journal of the Inter-American Foundation

Grassroots Development Journal of the Inter-American Foundation Enterprise at the Grassroots VOLUME 29 NUMBER 1 2008 Lester Salamon: Business Social Engagement in Latin America The Inter-American Foundation (IAF), an independent foreign assistance agency of the United States government, was created in 1969 to promote self-help development by awarding grants directly to organizations in Latin America and the Caribbean. Its operating budget consists of congressional appropriations and funds derived through the Social Progress Trust Fund. Grassroots Development is published in English and Spanish by the IAF’s The Inter-American Foundation Office of Operations. It appears on the IAF’s Web site at www.iaf.gov in Larry L. Palmer, President English, Spanish and Portuguese versions accessible in graphic or text only format. Original material produced by the IAF and published in Grassroots Board of Directors Development is in the public domain and may be freely reproduced. Certain material in this journal, however, has been provided by other sources and Roger Wallace, Chair might be copyrighted. Reproduction of such material may require prior Jack Vaughn, Vice Chair permission from the copyright holder. IAF requests notification of any re- Kay Kelley Arnold production and acknowledgement of the source. Grassroots Development is in- Gary Bryner dexed in the Standard Periodical Directory, the Public Affairs Service Bulletin, the Thomas Dodd Hispanic American Periodical Index (HAPI) and the Agricultural Online Access Hector Morales (WORLD) database. Back issues are available on microfilm from University John Salazar Microfilms International, 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. To receive Thomas Shannon the journal, e-mail [email protected] or write to the following address: Grassroots Development Grassroots Development Journal of the Inter-American Foundation Inter-American Foundation Publication Editor: Paula Durbin 901 North Stuart St. -

World Bank Document

DWC-8703 Public Disclosure Authorized Kenyan Coffee Sector Outlook: A Framework for Policy Analysis Takamasa Akiyama Public Disclosure Authorized Division Working Paper No. 1987-3 May 1987 Public Disclosure Authorized Commodity Studies; and Projections Division Economic Analysis and Projections Department Economics and Research Staff The World Bank Division Working Papers report on work in progress and are circulated to stimulate discussion and comment. Public Disclosure Authorized KENYAN COFFEE SUB-SECTOR OUTLOOK: A FRAMEWORK FOR POLICY ANALYSIS Takamasa Akiyama May 1987 The World Bank does not accept responsibility for the views expressed herein which are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank or to its affiliated organizations. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions are the results of research supported by the Bank; they do not necessarily represent official policy of the Bank. The designations employed, the presentation of material, and any maps used in this document are solely for the convenience of the reader and do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Bank or its affiliates concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its boundaries, or national affiliation. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY .. ................................ 1 II. RECENT TRENDS IN KENYA'S COFFEE SUB-SECTOR . 3 III. SALIENT FEATURES OF KENYA'S COFFEE SUB-SECTOR . 8 IV. ANALYSIS OF KENYAN COFFEE PRODUCTION . 22 V. PRODUCTION PROSPECTS .... 28 VI. PROSPECTS FOR KENYA'S COFFEE SUPPLY/DEMAND BALANCE ........ 44 VIII. POLICY IMPLICATIONS ....... ................. 48 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: KENYA COFFEE: STOCKS, PRODUCTION, AVAILABILITY AND EXPORTS--1969 TO 1984/85 ............................. -

International Coffee Farms (ICFC) in Panama in 2014 and Peini Cacao Plantation in Belize in 2016

S U S T A I N A B L E S P E C I A L T Y A G R I C U L T U R E PANAMA COFFEE FARMLAND Ownership Opportunity PROVEN PRODUCT – IT’S COFFEE!! COFFEE FARMING, PROCESSING, MARKETING A $90 BILLION INDUSTRY WORLDWIDE AND SALES ALL DONE FOR YOU HIGH AND INCREASING DEMAND FOR 100% SECURITY OF CAPITAL SPECIALTY COFFEE – ASK STARBUCKS! YOU OWN THE LAND LIMITED SUPPLY OF PROVEN QUALITY SPECIALTY COFFEE IT’S DEEDED TO YOU STEADILY INCREASING SPECIALTY COFFEE SAFE, SECURE, PRIVATE AND DEPENDABLE PRICES SECURE SUSTAINABLE INCOME TOTALLY UNRELATED TO COMMERCIAL DOUBLE DIGIT AVERAGE ANNUAL RETURNS COFFEE VOLATILTY AND PRICES (proforma) UNCORRELATED TO THE (MANIPULATED) STEADY, RELIABLE AND COMPLETLY PASSIVE STOCK MARKET CASH FLOW PROVEN EXPERIENCED TURNKEY OPERATOR A SUSTAINABLE LEGACY INVESTMENT FOR YOUR HEIRS FOR YEARS TO COME SINCE 2014 SOCIAL REWARDS 45-PERSON OPERATIONS AND MANAGEMENT TEAM IN-PLACE HELP IMPROVE THE LIVES OF COFFEE FARM WORKERS IN PANAMA SUCCESSFUL HARVESTS IN 2015/16, 2016/17 & 2017/18 PROVIDE A DEPENDABLE CAREER WITH LIVING WAGES, MEDICAL AND PENSION 100% OF COFFEE SOLD EACH YEAR BENEFITS AND 21ST CENTURY LIVING ACCOMMODATIONS AND SERVICES. ON-SITE STATE-OF-THE-ART PROCESSING HELP FARM WORKERS AND THEIR CHILDREN MILL AND LABORATORY ATTEND SCHOOL FOR THE 1ST TIME Who is AgroNosotros? AgroNosotros (AgN) is a pioneering effort to vertically integrate the specialty coffee and fine flavor cacao industries, beginning with International Coffee Farms (ICFC) in Panama in 2014 and Peini Cacao Plantation in Belize in 2016. AgN is currently operating 11 specialty coffee farms in Boquete, Panama and 6 fine flavor organic cacao farms in Southern Belize. -

Analysis of Production Efficiency of Mexican Coffee-Producing Districts

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Analysis of Production Efficiency of Mexican Coffee-Producing Districts AAEA Annual Meetings, Selected Paper #134280 Providence, RI July 2005 Gabriela Cardenas, Dmitry Vedenov and Jack Houston Corresponding author: Dmitry Vedenov 315C Conner Hall Dept. of Ag. and Applied Economics University of Georgia Athens, GA 30602 Voice: (706) 542-0757 Fax: (706) 542-0739 E-mail: [email protected] Cardenas is a former M.S. student (graduated 2004), Vedenov is an assistant professor, and Houston is a professor at the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Georgia. © Copyright 2005 by Cardenas, Vedenov, and Houston. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Keywords: distance function, production systems, stochastic frontier, technical efficiency, coffee production, Mexico. Analysis of Production Efficiency of Mexican Coffee-Producing Districts Introduction The theory of economic growth recognizes the fundamental role of increases in agricul- tural outputs in achieving rural advancement (Ohkawa and Rosovsky, 1960; Johnston and Mellor, 1961; Johnston and Nielsen, 1966; Johnson, 2000). However, agricultural production in various regions of the world is often affected by price fluctuations at the global level. In particu- lar, if market changes were to depress prices of the main cash crop, the households that lack easy access to financial and factor markets might respond to these conditions by shifting production towards food crops as a self-insurance mechanism (DeJanvry, Fafchamps and Saudolet, 1991). -

Long-Run Effects of Childhood Exposure to Booms in Colombia

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Carrillo, Bladimir Working Paper Present Bias and Underinvestment in Education? Long-run Effects of Childhood Exposure to Booms in Colombia Working Paper, No. 007.2019 Provided in Cooperation with: Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM) Suggested Citation: Carrillo, Bladimir (2019) : Present Bias and Underinvestment in Education? Long-run Effects of Childhood Exposure to Booms in Colombia, Working Paper, No. 007.2019, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM), Milano This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/211166 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort -

Version 2 BOOKLET 1 Reading Subtest

Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure® (MTEL®) Version 2 BOOKLET 1 Reading Subtest Copyright © 2016 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O. Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004 Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure and MTEL are trademarks of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). Pearson and its logo are trademarks, in the U.S. and/or other countries, of Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). 06/16 Communication and Literacy Skills (01) Practice Test: Reading Readers should be advised that this practice test, including many of the excerpts used herein, is protected by federal copyright law. Test policies and materials, including but not limited to tests, item types, and item formats, are subject to change at the discretion of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Communication and Literacy Skills (01) Practice Test: Reading MULTIPLE-CHOICE QUESTION ANALYSES Read the passage below; then answer the six questions that follow. Elinor Ostrom and Resource Management 1 Human life depends on using natural resource management depends on the active resources such as water, land, and minerals participation of stakeholders in formulating and the plants and animals they sustain, as and enforcing rules for using the resource. well as cultural resources such as knowledge This basic strategy applies to small groups as and skills. Learning how to manage these well as to complex organizations that are resources wisely is, therefore, a task of great formed by a network of many teams of importance to the survival of the human stakeholders with diverse interests who take species. -

“Know Who Grows” Their Coffee: the Case of THRIVE Farmers Coffee

International Food and Agribusiness Management Review Volume 16, Issue 3, 2013 Helping Consumers “Know Who Grows” Their Coffee: The Case of THRIVE Farmers Coffee a b c Norbert L. W. Wilson , Adam Wilson and Keith Whittingham a Associate Professor, Auburn University, Department of Agricultural Economics & Rural Sociology 100 C Comer Hall, Auburn University, Alabama, 36849, USA b Farm to Market Specialist, THRIVE Farmers International Headquarters, 215 Hembree Park Drive, Suite 100, Roswell, Georgia, 30076, USA c Associate Professor of Sustainable Enterprise, Rollins College, Crummer Graduate School of Business, 1000 Holt Avenue—2772 Winter Park, Florida, 32789, USA Abstract Michael Jones is the CEO of THRIVE Farmers Coffee. THRIVE Farmers International is a socially-oriented start-up with a new model for the coffee supply chain. The traditional supply chain for coffee is often criticized as being exploitative of farmers and the environment. The THRIVE system allows farmers to own their product further along the supply chain. Thus, the farmers function like a vertically integrated operation, selling a high-value product and retain the corresponding profit margins—5 to 10 times what they would get in traditional markets. As a result, the THRIVE model connects farmers and consumers directly. THRIVE offers customers the value of “knowing who grows” their high quality coffee. In consideration of its value proposition and social goals, how does Michael grow THRIVE? This case is a teaching case suitable for an advanced undergraduate or graduate course in marketing or strategy. Keywords: specialty coffee, THRIVE Farmers’ Coffee, supply chain, fair trade Contact Author: Tel: 334.844.5616 Email: N. -

Special HSC Edition

wine makin HSC Edition No 2 2017 Special HSC Edition PEOPLE & ECONOMIC ACTIVITY Going Bananas 8 Dairy Production: Using beestop 17 Resources 20 Starbucks: An economic enterpise at a local scale 25 Gloria Jean’s Coffees: An economic enterprise at a local scale 46 Towards Sustainable Coffee: A Green Commodities program 51 Coffee Production 53 Big Data Series: Part 1: Big Data – Products & services 66 Part 2: Big Data – A changing world 80 Part 3: Understanding Big Data – Student activities 91 PROJECTS • REPORTS • RESOURCES • ARTICLES • REVIEWS EXECUTIVE 2018 President Lorraine Chaffer Vice Presidents Susan Caldis Grant Kleeman Sharon McLean Louise Swanson Minutes Secretary Milton Brown OFFICE OF THE GEOGRAPHY TEACHERS’ Honorary Treasurer ASSOCIATION OF NEW SOUTH WALES Grant Kleeman ABN 59246850128 Councillors Address: 67–73 St Hilliers Road Auburn NSW 2144 Paul Alger Postal Address: PO Box 699 Lidcombe NSW 1825, Australia Karen Bowden Telephone: (02) 9716 0378, Fax: (02) 9564 2342 Michael Da Roza (ACT) Website: www.gtansw.org.au Catherine Donnelly Email: [email protected] Adrian Harrison Keith Hopkins ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP (Subscriptions include GST) Personal membership $90.00 Nick Hutchinson Corporate membership (school, department or business) $180.00 Grace Larobina Concessional membership (retiree, part-time teacher or student) $40.00 David Latimer Primary corporate membership $50.00 John Lewis Alexandra Lucas John Petts Martin Pluss Melinda Rowe Public Officer Louise Swanson GEOGRAPHY BULLETIN Cover: Fishing Trawler, Coffs Harbour and Fish farming, NZ Sounds Editor The Geography Bulletin is a quarterly journal of The Geography Teachers’ Association of New South Wales. The ‘Bulletin’ embraces those natural and human phenomena Lorraine Chaffer which fashion the character of the Earth’s surface.