Economics of Crops in Developing Countries No 1 The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiple Resistance to Bacterial Halo Blight and Bacterial Leaf Spot In

PLANT PATHOLOGY / SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE DOI: 10.1590/1808‑1657000632018 Multiple resistance to bacterial halo blight and bacterial leaf spot in Coffea spp.* Resistência múltipla à mancha aureolada e à mancha foliar bacteriana em Coffea spp. Lucas Mateus Rivero Rodrigues1,2** , Suzete Aparecida Lanza Destéfano2,3 , Irene Maria Gatti de Almeida3***, Luís Otávio Saggion Beriam3 , Masako Toma Braghini1 , Oliveiro Guerreiro Filho1,4 ABSTRACT: Breeding for genetic resistance is an important RESUMO: O melhoramento de plantas para resistência genética method of crop disease management, due to the numerous é um método importante para o manejo de doenças, pelos inú- benefits and low cost of establishment. In this study, progenies meros benefícios e baixo custo de implementação. No presente of 11 Coffea species and 16 wild C. arabica accessions were estudo, progênies de 11 espécies de Coffea e 16 acessos selvagens de tested for their response to Pseudomonas syringae pv. garcae, the C. arabica foram testados quanto à resposta a Pseudomonas syringae causal agent of bacterial halo blight, a widespread disease in pv. garcae, agente causal da mancha aureolada, doença disseminada the main coffee-producing regions of Brazil and considered a nas principais regiões produtoras de café do Brasil e considerada limiting factor for cultivation in pathogen-favorable areas; and fator limitante para o cultivo em áreas favoráveis a patógenos; e also to P. syringae pv. tabaci, causal agent of bacterial leaf spot, também para P. syringae pv. tabaci, agente causal da mancha foliar a highly aggressive disease recently detected in Brazil. Separate bacteriana, doença altamente agressiva detectada recentemente no experiments for each disease were carried out in a greenhouse, Brasil. -

Net Zero by 2050 a Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector Net Zero by 2050

Net Zero by 2050 A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector Net Zero by 2050 A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector Net Zero by 2050 Interactive iea.li/nzeroadmap Net Zero by 2050 Data iea.li/nzedata INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY The IEA examines the IEA member IEA association full spectrum countries: countries: of energy issues including oil, gas and Australia Brazil coal supply and Austria China demand, renewable Belgium India energy technologies, Canada Indonesia electricity markets, Czech Republic Morocco energy efficiency, Denmark Singapore access to energy, Estonia South Africa demand side Finland Thailand management and France much more. Through Germany its work, the IEA Greece advocates policies Hungary that will enhance the Ireland reliability, affordability Italy and sustainability of Japan energy in its Korea 30 member Luxembourg countries, Mexico 8 association Netherlands countries and New Zealand beyond. Norway Poland Portugal Slovak Republic Spain Sweden Please note that this publication is subject to Switzerland specific restrictions that limit Turkey its use and distribution. The United Kingdom terms and conditions are available online at United States www.iea.org/t&c/ This publication and any The European map included herein are without prejudice to the Commission also status of or sovereignty over participates in the any territory, to the work of the IEA delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Source: IEA. All rights reserved. International Energy Agency Website: www.iea.org Foreword We are approaching a decisive moment for international efforts to tackle the climate crisis – a great challenge of our times. -

Topic 09 Secondary Metabolites

4/9/2013 Topic 09 Secondary Metabolites Raven Chap. 2 (pp. 30‐35) Bring pre-washed white t-shirt to lab this week! I. Plant Secondary Metabolites A. Definitions 1))y Secondary Metabolism- 1a) Metabolite- 1 4/9/2013 I. Plant Secondary Metabolites B. Examples Compound Example Source Human Use ALKALOIDS Codeine Opium poppy Narcotic pain relief; cough suppressant Nicotine Tobacco Narcotic; stimulant Quinine Quinine tree Used to treat malaria; tonic Cocaine Coca Narcotic, tea, anesthetic, stimulant PHENOLICS Lignin Woody plants Hardwood furniture & baseball bats Tannin Leaves, bark, acorns Leather tanning, astringents Salicin Willows Aspirin precursor Tetrahydrocannabinol Cannabis Treatment for glaucoma & nausea TERPENOIDS Camphor Camphor tree Component of medicinal oils, disinfectants Menthol Mints & eucalyptus Strong aroma; cough medicines I. Plant Secondary Metabolites C. Ecology Steppuhn et al. 2004. PLoS Biology 2: 1074-1080. 2 4/9/2013 I. Plant Secondary Metabolites C. Ecology Nicotine negatively affects function of herbivores. Nicotine is a neurotoxin. Nicotine is made in roots and transported to shoots via xylem. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) 3 4/9/2013 Most potential herbivores cannot deal with nicotine. The tobacco hornworm (a moth larva) can sequester and secrete nicotine, with some energetic cost. Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Baldwin, IT. 2001. Plant Physiology 127: 1449-1458. 4 4/9/2013 Leaf Nicotine Content Unattacked Attacked Plants Plants Mechanism 1. Herbivory induces jasmonic acid (JA) production. 2. JA to roots, stimulates nicotine synthesis. 3. Nicotine to shoots 5 4/9/2013 I. Plant Secondary Metabolites C. Ecology I. Plant Secondary Metabolites C. Ecology Jasminum 6 4/9/2013 I. Plant Secondary Metabolites D. -

Coffee and Its Effect on Digestion

Expert report Coffee and its effect on digestion By Dr. Carlo La Vecchia, Professor of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, Dept. of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy. Contents 1 Overview 2 2 Coffee, a diet staple for millions 3 3 What effect can coffee have on the stomach? 4 4 Can coffee trigger heartburn or GORD? 5 5 Is coffee associated with the development of gastric or duodenal ulcers? 6 6 Can coffee help gallbladder or pancreatic function? 7 7 Does coffee consumption have an impact on the lower digestive tract? 8 8 Coffee and gut microbiota — an emerging area of research 9 9 About ISIC 10 10 References 11 www.coffeeandhealth.org May 2020 1 Expert report Coffee and its effect on digestion Overview There have been a number of studies published on coffee and its effect on different areas of digestion; some reporting favourable effects, while other studies report fewer positive effects. This report provides an overview of this body of research, highlighting a number of interesting findings that have emerged to date. Digestion is the breakdown of food and drink, which occurs through the synchronised function of several organs. It is coordinated by the nervous system and a number of different hormones, and can be impacted by a number of external factors. Coffee has been suggested as a trigger for some common digestive complaints from stomach ache and heartburn, through to bowel problems. Research suggests that coffee consumption can stimulate gastric, bile and pancreatic secretions, all of which play important roles in the overall process of digestion1–6. -

Phenolic Compounds in Coffee1

M I N I R E V I E W Phenolic compounds in coffee1 Adriana Farah and Carmen Marino Donangelo* Laboratório de Bioquímica Nutricional e de Alimentos. Departamento de Bioquímica, Instituto de Química, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Cidade Universitária, CT, Bloco A, Sala 528-A. Ilha do Fundão, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, 21949-900, Brazil. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites generally involved in plant adaptation to environmental stress conditions. Chlorogenic acids (CGA) and related compounds are the main components of the phenolic fraction of green coffee beans, reaching levels up to 14 % (dry matter basis). These compounds have a number of beneficial health properties related to their potent antioxidant activity as well as hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic and antiviral activities. The main groups of CGA found in green coffee beans include caffeoylquinic acids, dicaffeoylquinic acids, feruloylquinic acids, p-coumaroylquinic acids and mixed diesters of caffeic and ferulic acids with quinic acid, each group with at least three isomers. During coffee processing, CGA may be isomerized, hydrolyzed or degraded into low molecular weight compounds. The high temperatures of roasting also produce transformation of part of CGA into quinolactones and, along with other compounds, melanoidins. This review focuses on the chemical characteristics, biosynthesis, and distribution of CGA and related compounds in coffee. The influence of genetic, physiological and environmental factors as well as processing on the chemical composition of coffee beans is discussed. The impact of CGA composition of green coffee on cup quality is also approached. Despite the existence of substantial published information on the total levels of CGA in coffee, more research is needed on the composition of minor phenolic compounds and specific CGA isomers (and related substances) in green and roasted coffee beans, as well as their impact on coffee quality. -

Identification and Quantification of Adulterants in Coffee

foods Communication Identification and Quantification of Adulterants in Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Using FT-MIR Spectroscopy Coupled with Chemometrics Mauricio Flores-Valdez 1 , Ofelia Gabriela Meza-Márquez 2 , Guillermo Osorio-Revilla 2 and Tzayhri Gallardo-Velázquez 1,* 1 Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas-Santo Tomás, Departamento de Biofísica, Prolongación de Carpio y Plan de Ayala S/N, Col. Santo Tomás, Alcaldía Miguel Hidalgo, Ciudad de México C.P. 11340, Mexico; [email protected] 2 Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas-Zacatenco, Departamento de Ingeniería Bioquímica, Av. Wilfrido Massieu S/N, Esq. Cda, Miguel Stampa, Col. Unidad Profesional Adolfo López Mateos, Zacatenco, Alcaldía Gustavo A. Madero, Ciudad de México C.P. 07738, Mexico; [email protected] (O.G.M.-M.); [email protected] (G.O.-R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-(55)-5729-6000 (ext. 62305) Received: 24 May 2020; Accepted: 28 June 2020; Published: 30 June 2020 Abstract: Food adulteration is an illegal practice performed to elicit economic benefits. In the context of roasted and ground coffee, legumes, cereals, nuts and other vegetables are often used to augment the production volume; however, these adulterants lack the most important coffee compound, caffeine, which has health benefits. In this study, the mid-infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (FT-MIR) technique coupled with chemometrics was used to identify and quantify adulterants in coffee (Coffea arabica L.). Coffee samples were adulterated with corn, barley, soy, oat, rice and coffee husks, in proportions ranging from 1–30%. A discrimination model was developed using the soft independent modeling of class analogy (SIMCA) framework, and quantitative models were developed using such algorithms as the partial least squares algorithms with one variable (PLS1) and multiple variables (PLS2) and principal component regression (PCR). -

GRAS Notice GRN 868 Agency Response Letter -Coffee Fruit Extract

U.S. FOOD & DRUG ADMINISTRATI ON CENTER FOR FOOD SAFETY &APPLIED NUTRITION Ashish Talati Amin Talati Wasserman, LLP 100 S. Wacker Drive Suite 2000 Chicago, IL 60606 Re: GRAS Notice No. GRN 000868 Dear Mr. Talati: The Food and Drug Administration (FDA, we) completed our evaluation of GRN 000868. We received the notice that you submitted on behalf of VDF FutureCeuticals, Inc. (VDF) on June 10, 2019, and filed it on August 19, 2019. VDF submitted an amendment to the notice on November 1, 2019, that clarified information related to the description of coffee fruit extract, batch compliance with specifications, dietary exposure, safety studies, and analytical method validation. The subject of the notice is coffee fruit extract for use as an ingredient and as an antioxidant in certain beverages, including flavored waters, coffee, tea, ready-to-mix (RTM) beverages, fruit juices, and vegetable juices/blends; nutritional and replacement milk products (pre-workout); clusters/bars; chocolate; candy; and chewing gum, at levels ranging from 20 mg to 300 mg/serving.1 This notice informs us of VDF ' sview. that these uses of coffee fruit extract are GRAS through scientific procedures. Our use of the term, "coffee fruit extract" in this letter is not our recommendation of that term as an appropriate common or usual name for declaring the substance in accordance with FDA's labeling requirements. Under 21 CFR 101.4, each ingredient must be declared by its common or usual name. In addition, 21 CFR 102.5 outlines general principles to use when establishing common or usual names for nonstandardized foods. -

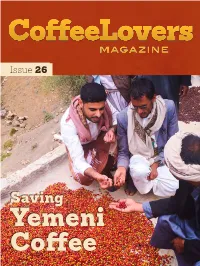

The Journey of One Man Trying to Save Yemeni Coffee (2015)

Issue 26 Saving Yemeni Coffee Coffee at its Origin The journey of one man trying to save Yemeni Coffee Ummah Wide Interviews Mokhtar Alkhanshali of Mocha Mill ummah wide: We are with Mokhtar mokhtar alkhanshali: I was recently talking Alkhanshali, the President and Founder of Mocha to one of my childhood mentors, Nasseam Mill — Yemeni Speciality Coffee, a company with a Elkarra, and he was reminding me that when I powerful social mission that is bridging the worlds was in High School I was always talking about of coffees roots in Yemen with the speciality coffee coffee in Yemen and the history of coffee in industry in the United States. One of the incredible Yemen. In particular he said I was talking things about this project is that you stand at the about the issue of Qat, the locally consumed intersection of two amazing histories, on one side stimulant in Yemen and how it’s taken the place you come from a family who has been growing of coffee in agriculture and someone needs to coffee for hundreds of years in Yemen, the first do something about it. Stephen Ezill, one of place to cultivate and commercialize coffee in the my friends at Boot Coffee said that his brother world. On the other side you are the first Arab/ called me a hero of a thousand faces because Yemeni certified speciality coffee Q grader. What there are so many different ways of looking can you tell us about these two worlds and how at what I am doing and different routes that you came to this moment in your life founding guided me to this point here. -

Economics of Sustainable Coffee Production in Los Santos, Costa Rica

Economics of Sustainable Coffee Production in Los Santos, Costa Rica Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in International Development Studies at Wageningen University and Research Centre (WUR), The Netherlands By Thom van Wesel 1 2 ‘Economics of Sustainable Coffee Production in Los Santos, Costa Rica’ Course Code: DEC 80433 Author: Thom van Wesel Registration Number: 880617-941-060 Supervisors: Fernando Saenz CINPE, Costa Rica Rob Schipper Wageningen University and Research Centre (WUR) Development Economics | Wageningen University & Research Centre | August 2012 3 Acknowledgement The period working on this thesis represented both a challenging and an invaluable experience. From the moment I started my thesis I have acquired remarkable and new experiences with regards to studying and living abroad, familiarizing oneself with a new culture, language and above all people. For I am very grateful to the persons who have enabled and supported me throughout this thesis. Without them, bringing my thesis to a good end would have been far more difficult and challenging. First of all I would like to thank the household that were willing to participate in my research. I have been amazed often by their hospitality, kindness and openness of families. The families and persons I have encountered have always been willing to receive my, make time and help me with any questions. This would have been very hard to reach without the help of the cooperative ‘Cooperative de Caficultores de Llano Bonito' (CoopeLlanoBonito) whose employees were very helpful in establishing contact with producers. In addition, I would like to thank my supervisors: Rob Schipper, Kees Burger and Fernando Saenz. -

Identification of Characterizing Aroma Components of Roasted Chicory

Article Cite This: J. Agric. Food Chem. XXXX, XXX, XXX−XXX pubs.acs.org/JAFC Identification of Characterizing Aroma Components of Roasted Chicory “Coffee” Brews Tiandan Wu and Keith R. Cadwallader* Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, University of Illinois at Urbana−Champaign, 1302 West Pennsylvania Avenue, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: The roasted and ground root of the chicory plant (Cichorium intybus), often referred to as chicory coffee, has served as a coffee surrogate for well over 2 centuries and is still in common use today. Volatile components of roasted chicory brews were identified by direct solvent extraction and solvent-assisted flavor evaporation (SAFE) combined with gas chromatography−olfactometry (GC−O), aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA), and gas chromatography−mass spectrometry (GC−MS). A total of 46 compounds were quantitated by stable isotope dilution analysis (SIDA) and internal standard methods, and odor-activity values (OAVs) were calculated. On the basis of the combined results of AEDA and OAVs, rotundone was considered to be the most potent odorant in roasted chicory. On the basis of their high OAVs, additional predominant odorants included 3-hydroxy-4,5-dimethyl-2(5H)-furanone (sotolon), 2-methylpropanal, 3-methylbutanal, 2,3- dihydro-5-hydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one (dihydromaltol), 1-octen-3-one, 2-ethyl-3,5-dimethylpyrazine, 4-hydroxy-2,5- dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone (HDMF), and 3-hydroxy-2-methyl-4-pyrone (maltol). Rotundone, with its distinctive aromatic woody, peppery, and “chicory-like” note was also detected in five different commercial ground roasted chicory products. -

Summary of the Application: DRIED COFFEE CHERRY of Coffea Sp

Summary of the application: DRIED COFFEE CHERRY of Coffea sp. (Cascara) Applicant: LUIGI LAVAZZA SpA, Via Bologna,32, 10152 Torino, ITALY This is an application for notification to place DRIED COFFEE CHERRY (commonly referred to as Cascara), from Coffea sp., on the market in the European Union (EU) for use as an ingredient in a herbal tea/infusion referred to as “Coffee cherry tea”, which is prepared by brewing the DRIED COFFEE CHERRY. This application is submitted pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on novel foods, and specifically corresponds to the category covered in Article 2 (iv) “food consisting of, isolated from or produced from plants or their parts, except when the food has a history of safe food use within the Union and is consisting of, isolated from or produced from a plant or a variety of the same species obtained by traditional propagating practices which have been used for food production within the Union before 15 May 1997.” The application was prepared according to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guidance on the preparation and presentation of an application for notification of a Traditional Food in the context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. Evidence of the consumption of “Coffee cherry tea” in Ethiopia dates back to before the 9th century; “Coffee cherry tea” is indeed commonly used as substitute for coffee in Ethiopia and Yemen. In the scientific literature and in this notification, the term DRIED COFFEE CHERRY refers to the outer part of coffee fruit, the husk and pulp, and accounts for almost 45% of the fresh berry. -

Understanding the Evolving Roles of Outbound Education Tourism in China: Past, Present, and Future

Athens Journal of Tourism - Volume 7, Issue 2, June 2020 – Pages 100-116 Understanding the Evolving Roles of Outbound Education Tourism in China: Past, Present, and Future By Sandy C. Chen* This paper discusses the evolving roles of outbound education tourism in China. To provide a thorough understanding, it first surveyed the origins and philosophy of travel as an educational device as well as education travelers’ motivations in Chinese history from the first pioneers in the Confucian era to the late 20th century. Then, it described key events and factors that have stimulated the development of the outbound education tourism in modern China and its explosive growth in the 21st century. Through in-depth personal interviews, the study developed a set of measures that reflected present Chinese students’ expectations of traveling abroad to study. A follow-up large-scale survey among Chinese students studying in the United States revealed two dimensions underlining these expectations: Intellectual Growth and Lifestyle. The findings of the study have significant implications for key stakeholders of higher education such as administrators, marketers, faculty, staff, and governmental policy-making agencies. Keywords: Education tourism, Outbound tourism, Chinese students, Travel motivation, Expectations. Introduction Traveling abroad to study, which falls under the definition of education tourism by Ritchie et al. (2003), has become a new sensation in China’s outbound tourism market. Indeed, since the start of the 21st century, top colleges and universities around the world have found themselves welcoming more and more Chinese students, who are quickly becoming the largest group of international students across campuses. Most of these students are self-financing and pay full tuition and fees, thus every year contributing billions of dollars to destination countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Germany, France, and Singapore.